Pepper Shaker

Title

Subject

Description

Today, pepper has become such a household staple that we hardly spare a thought to where it comes from. Yet black pepper, cultivated in East Asia, is a long ways from home in a pepper shaker on the American dinner table. (Figure I) Pepper’s modern availability masks the complexity of the global systems involved in its transportation, commoditization, and production. Here we will analyze how a pepper shaker (and its contents) along with countless other products, construct and facilitate the creation of a global commodity chain spanning across oceans, connecting the rainy country of Sumatra to the American midwestern city of Omaha, Nebraska. Commodity chains such as this one link societies and environments around the world through the exploitation of the natural environment and indigenous peoples and the globalization of resources, like pepper, in the development of global trade. Though these themes of global supply and demand and their consequences are not revolutionary, we are exploring the history of pepper cultivation in Sumatra and the commoditization of pepper in the American West (including Omaha) as a means to demonstrate how commoditization of globally-sourced goods like pepper allows international consumers to utilize material products while ignoring their impacts on the peoples and environments involved in their production. This strips these resources of their global significance and creates a pattern of consumption divorced from morality.

Omaha, Nebraska, a major junction of the transcontinental railroad, is one of the many cities which allowed pepper to become a global product. Referred to as the “Gateway City” (Larsen & Cottrell, 1983, 26), Omaha facilitated the distribution and consumption of pepper, along with many other goods such as, fruits and vegetables, grains, livestock, cotton, tobacco, household and agricultural machines, electricity, and petroleum to name a few. Omaha’s many intersecting rail lines ensured that the American had constant, inexpensive access to global resources. By the 19th century millions of tons of pepper were reaching the United States from overseas (Smith 2004, 66). However, pepper was just another comfort commodity, looked over as a part of the household table or a railcar dining set (Figure 4). This flow of cheap and easily accessible goods enabled the creation of a global commodity chain; a “network of economic links which integrate transnational labour processes and corporations involved in global sourcing and global marketing of products” (A Dictionary of Sociology, 2018).

The continuation of the transcontinental railroad through Omaha signified to many the continuation and realization of the American Manifest Destiny:

“...Omaha was the starting point of the grandest undertaking God ever witnessed in the history of the world” (Larsen & Cottrell, 1983, 27).

The Western world saw this expansion and modernization as their destiny, American society mimicking globalization occurring worldwide. Omaha built its early economic foundation in commerce from the railroads and the people of Omaha reaped the benefits despite the unseen systems of social and environmental exploitation.

The complex and global system of pepper production and transport which makes this spice so readily available has drastically impacted both the environment and the culture of the community involved in its commoditization, however. Truly a story of globalization, pepper’s history begins in East Asia where it grows in tropical, rainy regions such as Sumatra. Although production of this crop remains limited to these regions even to this day, records indicate that pepper was exported to Mediterranean markets as early as the first century (Pliny 1855, 112). As Western cultures came into greater contact with these regions of production, they established more and more trade routes until, in the early 1800s, the port of Salem, MA became “the world’s premier pepper shipper, controlling the Sumatra market and re-exporting 7.5 million pounds a year,” (Smith 2004, 66). The unlikely fact that a port located halfway around the world from Sumatra could control this market so completely reflects both the globalization of this industry and the distance between producers and consumers. American (and, by extension, Omahan) pepper consumers had little to no concept of where this spice came from in the nineteenth century, and could not have possibly imagined how the system which provided them with this mundane resource was impacting the people and the environment involved in its production. Yet, despite consumer ignorance of the effects of pepper production on the people and environment of Sumatra, these effects were numerous, and their legacy continues to impact Sumatra to this day.

One way cultivation of Piper nigrum has altered the environment of Sumatra is through the rampant deforestation which it inspired. Cultivation of pepper had always demanded some forest clearance; however, it was not until the Anglo-Dutch introduction of plantation agriculture that the cultivation of P. nigrum in Sumatra became truly detrimental to the local environment.. Prior to the fifteenth century, before pepper was cultivated primarily for export, the indigenous people of Sumatra either foraged for this crop or grew it in private gardens (Reid 1995, 98). This practice of limited cultivation in small, private gardens rotated only once every one to two years had very little impact on the densely forested environment in which pepper already grew naturally. In fact, Reid goes as far as to deem the impact of pepper cultivation on the Sumatran environment prior to the fifteenth century as “negligible,” (Reid 1995, 98).

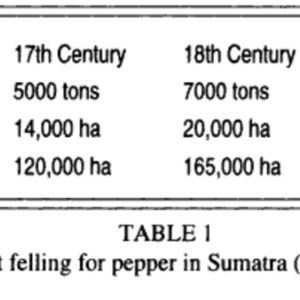

This style of cultivation, although environmentally sustainable, would prove incapable of sustaining the larger scale of production which Western European demand necessitated. Once the English and Dutch established trade routes with Sumatra and demand for pepper exports grew, the growing of pepper transitioned from the indigenous, horticultural style to the European-imposed plantation style. By the eighteenth century, the Anglo-Dutch had successfully implemented plantation-style cultivation across Sumatra and, through a system of rewards, punishment, and constant vigilance, had developed tight control over this industry. A contemporary historian during this period, William Marsden, describes Dutch regulation of pepper production in Sumatra in 1811, writing, “rewards and punishments are distributed to the planters as they appear, from the degree of their industry or remissness, deserving of either” (Marsden 1811, chapter 7 and Figure V). The large-scale, militant production of pepper which had become the norm by the beginning of the nineteenth century had a severe impact on the Sumatran environment, especially in terms of deforestation. In order to meet the demands of the European spice traders, planters had to cultivate pepper constantly. This led to rapid depletion of nutrients in the soil, which meant that growers would have to clear new areas of forest to plant new gardens every few years. Using statistics on the exportation of pepper crops as well as knowledge of these farming practices, Reid estimates the amount of primary forest cleared for pepper cultivation from the 17th to the 19th century to be 760,000ha (Figure II).

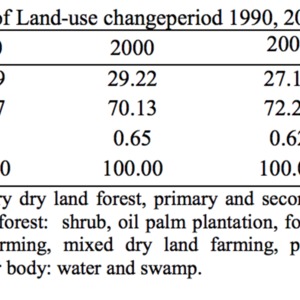

As these figures demonstrate, global consumption of pepper had a drastic impact on the Sumatran environment during this period, whether global consumers were aware of this impact or not. Indeed, deforestation continues to impact Sumatra today (Figure III). As recently as 2014, CNN noted that deforestation as a means of increasing agricultural production continues to threaten Sumatran forest, with deforestation destroying an additional 25% of the Sumatran forest between 1985 and 2008 (Watts 2013, 1). Taking into account both the immediate and long term impacts of pepper consumption on Sumatran deforestation, then, one must acknowledge the grave effect which the seemingly trivial act of pepper consumption had on the Sumatran environment. Considering the system of pepper production, export, and consumption holistically reveals the power of even small acts to cause dire environmental changes in our current, globalized system, and cautions against the dangers of blind consumerism.

Another unintended consequence of pepper cultivation in Sumatra, the commoditization of Sumatran women which resulted from plantation-style pepper cultivation further demonstrates the ripple effect simple acts can have within a global system, reinforcing the need for conscientious consumerism. Most scholars agree that, prior to European domination of the region, Sumatran women enjoyed a comparatively higher societal status than did their western counterparts (Andaya 1995, 166-170). This elevated social status was, as Andaya contends, directly linked to the control which Sumatran women weided over an important resource: pepper. Since women were primarily in charge of the planting, cultivation, harvesting and selling pepper, women earned prestige in Sumatran society as valuable contributors/economic producers of this coveted crop. Consequently, due to their participation in the pepper economy, Sumatran women enjoyed more respect and freedom than did the Western women who would later buy the crops they produced.[1] The equalizing effects of horticultural pepper cultivation endured for many centuries; however, they, too, like the Sumatran forest, would become collateral damage in the battle to keep up with demands for pepper.

European implementation of plantation-style cultivation of pepper in Sumatra led to rampant deforestation. But the detrimental impacts of European intervention in Sumatra did not end there. As Europeans restructured the Sumatran economy to meet the growing global demands for pepper, they removed women from the pepper economy completely, lowering women’s social status through the destruction of their once-valued societal role. Ramusack explains the ramifications European-style plantation cultivation had for women, writing:

As European demands led to large-scale plantations, men displaced women, for whom plantation labor was incompatible with domestic duties and contrary to religious injunctions about female modesty. Because coastal centers were notorious sites of prostitution, the same proscriptions also restricted women from taking their pepper crops to the cities for sale to Europeans (Ramusack 1997, 126).

As Ramusack reveals, the European implementation of the plantation system of cultivating pepper had serious consequences for Sumatran women, at once depriving them of their share in a lucrative and societally valued industry and imposing new, limiting ideas of modesty upon them. Ironically, due to the rigidity of the European ideals of modesty which prohibited women from engaging in traditional means of supporting themselves, many turned to prostitution. In his travel to Sumatra in 1703, Nieuhoff remarks, “The women are well fhaped, and of a fairifh complexion, with very white teeth; they make no account of chaftity, nor look upon it as a difgrace to explofe themfelves for money,” (Nieuhof 2002, 189). The radical transition from a society which not only provided women the means of supporting themselves but also valued them for this trait, to a society which deprived women of the means of supporting themselves and then derided their desperation, demonstrates the expendability of human beings within a globalized system. For the women of Sumatra, Western European commoditization of pepper represented the death knell of their societal status. Moreover, it constituted the devastation of the hopes, dreams, and dignity of many women who were once independent but now had to support themselves through prostitution. However, the pain of these women remained invisible to the consumers buying pepper off their supermarket shelves or pouring it over their eggs in the morning. By the time pepper entered the small, glass pepper shaker, it had lost all connection with the place and people involved in its production. Thus, while standing in the checkout line or eating his/her eggs, this global consumer did not have to consider the winners or the losers in the system which produced the product they were consuming. The deforestation or disenfranchisement of women in Sumatra was no less real, however, despite the consumer’s blissful ignorance. Consequently, while the global system may protect consumers from the mental burden of the truths behind the products they consume, it does not protect consumers from the immorality which they endorse through their consumption of these products.

It is evident that the cultivation of pepper has had immense global impacts. The average American entering a midwest grocery store in Omaha, NE, enjoys the luxury of tossing the pepper grinder into the cart without a second thought. The commoditization of goods such as pepper has obscured the exploitation of people and environments involved in the production of these products. Modern technology has made nature cheap for humans to use, but has treating people cheaply become the price? The Anthropocene is a new geological epoch in the record of time defined by human induced change. But many of these human induced changes, meant to benefit the growing human aggregate, have actually become dehumanizing as our exploitation has led to the use of humans and cultures only as resources. The story of pepper provides one example of globalized commodification disguising environmental histories. The effect of this trade on the region of production in Sumatra reflects the dangers of a system which divorces products from their environmental and cultural significance. In commercializing the natural resource of pepper, the global system has, in effect, separated the act of consumption from the moral consequences for the region and the people of Sumatra. Thus, increasingly global commodity chains provide one example of anthropogenic change that is decreasingly anthropocentric.

[1] Additionally, due to the increased value women earned as producers/economic contributors in East Asian Society, Sumatran women also enjoyed greater social advantages than did women in Western society. For example, bilateral descent was a widespread occurrence in Sumatra, and male-female roles in indigenous rituals were largely complementary (Andaya 1995, 3).

Creator

Hannah Yackley

Source

Andaya, Barbara. "Women and Economic Change: The Pepper Trade in Pre-Modern Southeast Asia." Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 38, no. 2 (1995): 165-190.

"Aksarben Foundation History - Our Past, Present and Future." Aksarben Foundation. 2018. Accessed November 07, 2018. https://www.aksarben.org/heritage/.

Basyuni, et al. “Deforestation Trend in North Sumatra over 1990-2015.” IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, vol. 122, no. 1, 2018, pp. 4.

Bathke, Deborah J., Robert J. Oglesby, Clinton M. Rowe, and Donald A. Wilhite. "University of Nebraska." Encyclopedia of Global Warming and Climate Change, September 2014, 14-16. Accessed November 6, 2018. doi:10.4135/9781412963893.n675.

Bostwick, L., & Frohardt, H. (1934). Dinner on a Dining Car[Photograph]. Bostwick-Frohardt Collection, Durham Museum, Omaha.

"commodity chains." A Dictionary of Sociology. . Encyclopedia.com. (November 13, 2018). https://www.encyclopedia.com/social-sciences/dictionaries-thesauruses- pictures-and-press-releases/commodity-chains

Chains, Absorbing." Encyclopedia of Statistical Sciences, 2004. Doi: 10.1002/0471667196.ess0008.

Gaveau, Wandono, & Setiabudi. "Three Decades of Deforestation in Southwest Sumatra: Have Protected Areas Halted Forest Loss and Logging, and Promoted Re-Growth?" Biological Conservation 134, no. 4 (2007): 495-504.

Grant, H. Roger. ""Minnesota's Good Railroad": The Omaha Road." Minnesota History 57, no. 4 (2000): 198-210. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20188231.

Greever, William S. "Railroad Revisionism." The Pacific Northwest Quarterly 53, no. 1 (1962): 44-45. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40487714.

"History." Omaha Steel. March 21, 2017. Accessed November 07, 2018. http://www.omahasteel.com/about-us/history/.

Larsen, L., & Cottrell B. (1983). The Gate City: A History of Omaha Lawrence H. Larsen Barbara J. Cottrell. Pruett Publishing Company

Larsen, & Larsen, Lawrence H. (2007). Upstream metropolis : An urban biography of Omaha and Council Bluffs. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Marsden, William. The History of Sumatra, Containing An Account of the Government, Laws, Customs, and Manners of the Native Inhabitants, with A Description of the Natural Productions, and Relation of the Ancient Political State of That Island. Third Ed. London: J.M'Creery, Black-Horse-Court, 1811.

Neiuhof, Johan. "Remarkable Voyages and Travels to the East-Indies." In A Collection of Voyages and Travels, Vol. 2, translated and edited by Awnsham Churchill, 146-275. Asian Educational Services, 2002.

Pliny the Elder. "Book XII." In The Natural History of Pliny. London: Henry G. Bohn, York Street, Covent Garden, 1855.

Potts, James B. "THE NEBRASKA CAPITAL CONTROVERSY, 1854—59." Great Plains Quarterly 8, no. 3 (1988): 172-82. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23531122.

Ramusack, Barbara. "Women and Gender in South and Southeast Asia." In Women's History in Global Perspective edited by Bonnie Smith, 125-150. Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1997.

Reid, Anthony. "Humans and Forests in Pre-colonial Southeast Asia." Environment and History 1, no. 1 (1995): 93-110.

Smith, J. N. "The King of Spices." World Trade 17, no. 11 (2004): 66. https://login.cuhsl.creighton.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=14738428&site=ehost-live

Watts, Jenni. "The Devastation of Indonesia's Forests." CNN (October 14, 2013): https://www.cnn.com/2013/10/14/world/expedition-sumatra-episode-5-blog/index.html

Rights

Collection

Citation

Embed

Copy the code below into your web page