Vacuum Cleaner

Title

Vacuum Cleaner

Subject

Today, almost every American household has a vacuum cleaner. Yet, before the 1950s vacuum cleaners were a rare item. Americans experienced a lifestyle change after World War II. Their income increased and they bought homes in the suburbs. Americans spent some of their new wealth on items such as vacuum cleaners. Department stores like Sears-Kenmore encouraged consumers to buy the newest models. This 1948 Kenmore Commander was one very popular option. You could purchase it anywhere, including Omaha, NE. This increase in consumption had numerous environmental costs. Manufactures use natural resources and energy and produce waste. The rise of consumer appliances mirrors Great Acceleration trends that birthed the Anthropocene. The vacuum cleaner symbolizes these changes. Consumerism changed our economy, environment, and everyday lives.

Description

In many American households, a vacuum cleaner is a simple, ordinary, everyday item. It is an item pulled out of the linen closet on occasion to remove dust, dirt, and debris from household surfaces, then promptly shoved back into the closet until the next use. Mundane objects like this rarely warrant historical interest or attention, yet the vacuum cleaner means much more; it is a key feature in the narrative of consumerism. The vacuum cleaner symbolizes the rise of consumerism from the 1950s to the present. In that capacity, it played and continues to play an important role in the Anthropocene.

Like most technological innovations, vacuum cleaners went through various stages of development. It began as a tool for commercial enterprises and then expanded to use in private homes. The creator of the first ‘vacuum cleaner’ to use air movement and suction named a carpet sweeper is Daniel Hess of West Union, Iowa in 1860 (Gantz 2012,35). This carpet sweeper would draw in dust and dirt through the machine with an elaborate brush and bellows mechanism that sucked the dust into two water chambers. Numerous patents for improving the suction mechanism followed in subsequent years. Some patents included hand cranks for instance, while others…. With every new development, sweeping machines resembled modern upright vacuum cleaners more and more. On March 19, 1907, the U.S. patent office approved U.S. patent 847,947 for an apparatus for moving dust developed by David T. Kenney, which was the first mechanical suction in a vacuum (Gantz 2012, 49). Shortly thereafter, Hubert Booth made this design mobile, he created with coining the term ‘vacuum cleaner’, (Gantz 2012, 49). By the 1920s, vacuums were mass-produced for commercial and residential sale (Gantz 2012, 86).

Technical improvements are not simply the sole reason for Increasing use and sales of vacuum cleaners however. Until the 1940s, social issues and economic challenges limited demand. The stock market crash of 1929 and the onset of the Great Depression left many families in poverty. Household balance sheets from 1929-1932 show severe shrinkage in assets and real household liabilities increased by 16 percent (Mishkin 1978, 922). The beginning years of the Great Depression distinctively show the deterioration in financials that the majority of consumers suffered (Mishkin 1978, 923). After World War II, vacuum sales exploded. The late 1940s and early 1950s offered the perfect circumstances for the rise of vacuums, and consumerism more broadly in America. First, the spread of suburbia. Before World War II, only 13% of Americans lived in suburbs. After the war, suburbs were increasingly sold to consumers as the realization of the “American Dream” (Nicolaides et al. 2017). During the transition into a peacetime society, the federal government subsidized suburbanization in several ways, including underwriting low-interest loans and funding infrastructure projects like highways (Jackson 1985, 232) These new homes and neighborhoods were not equally available to all Americans, yet they nevertheless shaped national patterns of car and energy usage, spending and saving, and altered the fabrics of urban and suburban communities (Jackson 1985, 251).

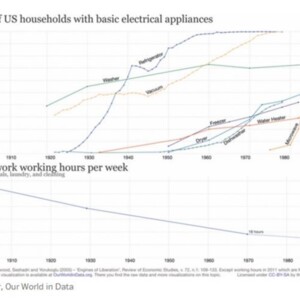

As urban growth expanded, so did the physical size of a typical house. These post-war homes were spacious, often including two bedrooms, extensive carpeting, and homeowners had the disposable income necessary to fill them with large furnishings. (The Social History 2014, 699). During the 1950s, average American incomes rose dramatically (The Social History 2014, 151). The proportion of their income spent on housing increased because of changes in the American lifestyle; as incomes rose, budgeting also rose due to inflation and new expenses that emerged (The Social History 2014, 150). At the beginning of the twentieth century, families spent 23 percent of their income on housing, 42.5 percent on food, and 14 percent on clothing. By the 1950s, families spent 27.2 percent on housing, 29.7 percent on food, 11.5 percent on clothing, and 31.6 percent on other things. (The Social History 2014,150). Much of this increase went to expenses such as utilities, and consumer goods such as lawnmowers, vacuum cleaners, furniture, and large appliances (The Social History 2014, 151). The widespread electrification of homes after 1948 encouraged the use of household appliances as well. Furthermore, the ‘other things’ that now constituted a significant portion of the average American family’s budget reflected a lifestyle change; it was now typical for homes to have plumbing, electricity, telephones, and to own automobiles. The American economic system evolved to cater to high consumption habits to foster prosperity, positive earning was more important than negative spending. New credit techniques emerged that “universalized the slogan ‘buy now, pay later'” (Bonneuil et al. 2016, 157). Using credit to buy items, allowed people to spend more than they currently had in their bank account.

As homes and neighborhoods changed, social roles for women shifted as well. Books, magazines, films, and other media painted an idyllic picture of the perfect stay-at-home housewife who took care of the home, raised the children, and provided a haven for her hardworking husband (Hardy 2017, 109). The cover of the Kenmore Ken Kart Owner’s Manual pictures a housewife using the 1948 Kenmore Bullet model. (Automatic Ephemera The woman is wearing a dress, heels, and an apron and is not failing to smile while vacuuming. This media furthermore created the housewife’s role as a household consumer and taught suburban women the ways of scientific housekeeping. “Scientific housekeeping” was the prescience way in which women ‘ran’ the house. Housewives were required to both keep the house clean and tidy, but also keep everyone within the household satisfied and happy; to do this, it took a way of precision and science. To be excellent in their role as a housekeeper, they looked for help to alleviate some of the backbreaking labor in fulfilling their duties and roles (Strasser 2000, 84): It was the combination of all these factors; the increase in American income, the increased house size, and the role of housewives which created the demand for vacuum cleaners during this time.

The 1948 Kenmore Commander or “Bullet” in the Durham Museum collection was a popular vacuum cleaner during this time. The Brand Kenmore had been selling appliances under Sears Roebuck since 1932. The Commander model was a sign of the times: this bullet cleaner had a striking resemblance to a 1000-pound navel artillery shell and was undoubtedly inspired by World War II (Gantz 2012, 125). Made out of Aluminum and polished, the vacuum had a maroon and copper look. Sears sold their products all over the world and Omaha was home to a Sears Roebuck office site. Located at Thirtieth and Farnam Streets in Omaha, Nebraska from 1928 and then re-locating to the Crossroads, Sears served as the department store of Omaha (Gonzalez 2018). The Sears, Roebuck, and Co. catalog was a household staple and the Amazon of its day. Sears, Roebuck, and Co. were at the forefront of the industry. A spokesperson for Sears once said “Our catalog helps to make merchandising history. When we announce a new issue in our catalog, our merchandise selections are news, and our prices are news (Kimball 1963, 213). By the 1960s sears was the world's largest retailer (The Associated Press 2018). The ubiquity of household appliances, made possible by Sears and other vendors, seemed to validate American pride in the superiority of the West (Glickman 1999, 8).

Omaha consumers were not limited to Sears, however. Smaller vacuum stores also existed during this period. 115 North 16th Street was the site for an Ace Vacuum Store. These stores proudly arranged their window displays to attract customers to buy the newest and latest model. Large corporations and local salesmen were very effective in their pursuit of sales. An excerpt from the New York Times titled “Dealings in Household Cleaners Already Top Prewar High” published on August 13, 1949. It noted that the number of household vacuum cleaners already passed the units sold in 1941, the year of the prewar record of sales. Another excerpt from The Times on July 21st, 1950, read “Factory sales of standard-size household vacuum cleaners in the first half of 1950 showed a 15.8 per cent increase…sales thus far this year total 1,695,178 units [and] sales in June were 20.5 per cent higher than in June 1949” (Vacuum Cleaner Sales 1950). It is evident the vacuum cleaner was a hot commodity with the increasing number of New York Times headliners on the subject.

Along with vacuum cleaners, consumers were also hooked on power. Americans became devoted to electric everything: can openers, lights, toothbrushes, knives, and much more. Americans continued to buy powered appliances from the same corporations, even as they provided fewer benefits (Strasser 2000, 84). Some technologies and household appliances did not work as effectively as marketed in advertisements. Freezers claimed to decrease shopping time by providing increased capacity (thus fewer trips). However, housewives only truly bought large amounts when they were on sale (Evans et al. 2001, 131). These new technologies and practices resulted in a habit of buying in excess. Betty Friedan, an American feminist writer, and activist wrote in 1963 “Why is it never said that the crucial function, the really important role that women serve as housewives is to buy more things for the house? (Fridean 1963, 299).

The 1950s was an era in which consumerism thrived and the consumer economy projected the power of American liberal democracy (608). Other countries tended to have other approaches and Europe specifically was naturally conservative in its philosophy of living (Whiteley 1987, 4). But after recovering economically from the war, Western Europe and Japan would quickly transition to mass consumerism as well. This American story would global: this was the onset of the Golden Age of what? Consumerism? In 1957, only 3 percent of Japanese households had an electric refrigerator, but by 1980 almost all households did (McNeill et al. 2014, 125). Countries began to embrace “Americanization, which according to environmental historians J.R. McNeill and Peter Engelke denoted “the high energy, materials-intensive American lifestyle, embodied in the automobile, household appliances, the freestanding house in the suburbs, and everyday consumer products” (McNeill et al. 2014 126).

Consuming became habitual all over the world. However, it was not always like this; consumer behavior was created. In the nineteenth century, companies and workers committed to a healthy balance of work and leisure. ‘Saint Monday’ (absenteeism) was well practiced, and workers would enjoy the privilege of having time off to relax and reset. Furthermore, practices of recycling were fundamental in the nineteenth century. In France during the 1860s, almost everything was reused: rags for paper, bone for tablets, buttons, phosphorus, and gelatin (Bonneuil et al., 2016). Recycling became embedded into society. Good housing keeping also minimized waste and several books came out during this time to teach the recycling of waste. However, entrepreneurs became to realize the profit behind consuming and the ability to create mass markets; in order for mass markets to create profit, they needed mass consumerism. Entrepreneurs now needed to enforce the idea of mass consumption upon consumers. “The explicit and paramount aim of politicians, industrialists, and advertisers alike was to create markets able to absorb the new productive capacities of Taylorist factories (Bonneuil et al., 2016, pg 154). While entrepreneurs began to make bigger profits, the environment was taking some of the costs.

The globalization of American consumerism had numerous unanticipated consequences. In the 1970s and 1980s, for instance, scientists discovered the refrigerants used in household appliances called “CFCs” (chlorofluorocarbons) were thinning the ozone layer. Household appliances were also various consumers of energy. Manufacturers combatted this issue by developing more efficient appliances (McNeill et al. 2014, 122). By 2002, they consumed on average 80 percent less energy than an appliance made in the 1980s (McNeill et al. 2014, 123). Nevertheless, as companies lowered energy use, more people continued to buy goods. As people accumulated more and more goods, it produced an enormous amount of waste. Consumers embraced the view that is it common and acceptable to discard products, even if simply to have a more up-to-date or appealing version (Whiteley 1987, 3). Any energy reduction was offset by increasing purchases and total energy consumption increased as a result. By (year) Fifteen percent of total electricity in China, for instance, was for refrigerators and household appliances. Consumerism, and its environmental consequences, had globalized (McNeill et al. 2014 124).

In part due to these patterns of increasing and wasteful consumption, the global economy threatened to outstrip ecological limits (McNeill et al. 124 134). Consumption affects the environment in multiple ways. In higher levels of production necessary to produce consumer appliances, which require large amounts of energy and material, large quantities of waste were produced as byproducts. On top of that, increased extraction and exploitation of natural resources, and waste damage on the environment accumulated. (Orecchia et al 2017, 1). An article by Jaia Syvistic, shows human energy expenditure since 1950 exceeds the energy expenditure across the entire prior 11,700 years of the Holocene (Elmqvist et al. 2021). . Resource demand influenced changes in population size, housing density, and consumption patterns (Elmqvist et al. 2021). In the years after the 1950s, hundreds of people around the globe began to attain levels of consumption unimaginable to their ancestors. The global economy’s effects on the planet became evident, and the economy was deeply reliant on the use of non-renewable resources such as fossil fuels and minerals.

While consumerism may have begun to thrive in the 1950s, the consumerism habit of postwar life continues to flourish today. As globalization and technological developments increase, the number of steps between people and the resources they use increases. This distance makes it progressively challenging for people to know and understand their consumptive decisions (Elmqvist et al. 2021). Ecosystem use is becoming commodified and commercialized. Small household appliances often have long supply chains associated with their production, and there is little transparency regarding the sustainability of any production process along the chain. It can be challenging, almost impossible to make positive choices for sustainable consumption with so many information steps within each step to understand or have information to inform consumption practices (Elmqvist et al. 2021).

It may seem that the vacuum cleaner is a simple, household appliance, but it is much more. It acts as a symbol of the beginning of an era of consumerism. An era that has deeply transformed our economy, environment, and everyday lives.

Like most technological innovations, vacuum cleaners went through various stages of development. It began as a tool for commercial enterprises and then expanded to use in private homes. The creator of the first ‘vacuum cleaner’ to use air movement and suction named a carpet sweeper is Daniel Hess of West Union, Iowa in 1860 (Gantz 2012,35). This carpet sweeper would draw in dust and dirt through the machine with an elaborate brush and bellows mechanism that sucked the dust into two water chambers. Numerous patents for improving the suction mechanism followed in subsequent years. Some patents included hand cranks for instance, while others…. With every new development, sweeping machines resembled modern upright vacuum cleaners more and more. On March 19, 1907, the U.S. patent office approved U.S. patent 847,947 for an apparatus for moving dust developed by David T. Kenney, which was the first mechanical suction in a vacuum (Gantz 2012, 49). Shortly thereafter, Hubert Booth made this design mobile, he created with coining the term ‘vacuum cleaner’, (Gantz 2012, 49). By the 1920s, vacuums were mass-produced for commercial and residential sale (Gantz 2012, 86).

Technical improvements are not simply the sole reason for Increasing use and sales of vacuum cleaners however. Until the 1940s, social issues and economic challenges limited demand. The stock market crash of 1929 and the onset of the Great Depression left many families in poverty. Household balance sheets from 1929-1932 show severe shrinkage in assets and real household liabilities increased by 16 percent (Mishkin 1978, 922). The beginning years of the Great Depression distinctively show the deterioration in financials that the majority of consumers suffered (Mishkin 1978, 923). After World War II, vacuum sales exploded. The late 1940s and early 1950s offered the perfect circumstances for the rise of vacuums, and consumerism more broadly in America. First, the spread of suburbia. Before World War II, only 13% of Americans lived in suburbs. After the war, suburbs were increasingly sold to consumers as the realization of the “American Dream” (Nicolaides et al. 2017). During the transition into a peacetime society, the federal government subsidized suburbanization in several ways, including underwriting low-interest loans and funding infrastructure projects like highways (Jackson 1985, 232) These new homes and neighborhoods were not equally available to all Americans, yet they nevertheless shaped national patterns of car and energy usage, spending and saving, and altered the fabrics of urban and suburban communities (Jackson 1985, 251).

As urban growth expanded, so did the physical size of a typical house. These post-war homes were spacious, often including two bedrooms, extensive carpeting, and homeowners had the disposable income necessary to fill them with large furnishings. (The Social History 2014, 699). During the 1950s, average American incomes rose dramatically (The Social History 2014, 151). The proportion of their income spent on housing increased because of changes in the American lifestyle; as incomes rose, budgeting also rose due to inflation and new expenses that emerged (The Social History 2014, 150). At the beginning of the twentieth century, families spent 23 percent of their income on housing, 42.5 percent on food, and 14 percent on clothing. By the 1950s, families spent 27.2 percent on housing, 29.7 percent on food, 11.5 percent on clothing, and 31.6 percent on other things. (The Social History 2014,150). Much of this increase went to expenses such as utilities, and consumer goods such as lawnmowers, vacuum cleaners, furniture, and large appliances (The Social History 2014, 151). The widespread electrification of homes after 1948 encouraged the use of household appliances as well. Furthermore, the ‘other things’ that now constituted a significant portion of the average American family’s budget reflected a lifestyle change; it was now typical for homes to have plumbing, electricity, telephones, and to own automobiles. The American economic system evolved to cater to high consumption habits to foster prosperity, positive earning was more important than negative spending. New credit techniques emerged that “universalized the slogan ‘buy now, pay later'” (Bonneuil et al. 2016, 157). Using credit to buy items, allowed people to spend more than they currently had in their bank account.

As homes and neighborhoods changed, social roles for women shifted as well. Books, magazines, films, and other media painted an idyllic picture of the perfect stay-at-home housewife who took care of the home, raised the children, and provided a haven for her hardworking husband (Hardy 2017, 109). The cover of the Kenmore Ken Kart Owner’s Manual pictures a housewife using the 1948 Kenmore Bullet model. (Automatic Ephemera The woman is wearing a dress, heels, and an apron and is not failing to smile while vacuuming. This media furthermore created the housewife’s role as a household consumer and taught suburban women the ways of scientific housekeeping. “Scientific housekeeping” was the prescience way in which women ‘ran’ the house. Housewives were required to both keep the house clean and tidy, but also keep everyone within the household satisfied and happy; to do this, it took a way of precision and science. To be excellent in their role as a housekeeper, they looked for help to alleviate some of the backbreaking labor in fulfilling their duties and roles (Strasser 2000, 84): It was the combination of all these factors; the increase in American income, the increased house size, and the role of housewives which created the demand for vacuum cleaners during this time.

The 1948 Kenmore Commander or “Bullet” in the Durham Museum collection was a popular vacuum cleaner during this time. The Brand Kenmore had been selling appliances under Sears Roebuck since 1932. The Commander model was a sign of the times: this bullet cleaner had a striking resemblance to a 1000-pound navel artillery shell and was undoubtedly inspired by World War II (Gantz 2012, 125). Made out of Aluminum and polished, the vacuum had a maroon and copper look. Sears sold their products all over the world and Omaha was home to a Sears Roebuck office site. Located at Thirtieth and Farnam Streets in Omaha, Nebraska from 1928 and then re-locating to the Crossroads, Sears served as the department store of Omaha (Gonzalez 2018). The Sears, Roebuck, and Co. catalog was a household staple and the Amazon of its day. Sears, Roebuck, and Co. were at the forefront of the industry. A spokesperson for Sears once said “Our catalog helps to make merchandising history. When we announce a new issue in our catalog, our merchandise selections are news, and our prices are news (Kimball 1963, 213). By the 1960s sears was the world's largest retailer (The Associated Press 2018). The ubiquity of household appliances, made possible by Sears and other vendors, seemed to validate American pride in the superiority of the West (Glickman 1999, 8).

Omaha consumers were not limited to Sears, however. Smaller vacuum stores also existed during this period. 115 North 16th Street was the site for an Ace Vacuum Store. These stores proudly arranged their window displays to attract customers to buy the newest and latest model. Large corporations and local salesmen were very effective in their pursuit of sales. An excerpt from the New York Times titled “Dealings in Household Cleaners Already Top Prewar High” published on August 13, 1949. It noted that the number of household vacuum cleaners already passed the units sold in 1941, the year of the prewar record of sales. Another excerpt from The Times on July 21st, 1950, read “Factory sales of standard-size household vacuum cleaners in the first half of 1950 showed a 15.8 per cent increase…sales thus far this year total 1,695,178 units [and] sales in June were 20.5 per cent higher than in June 1949” (Vacuum Cleaner Sales 1950). It is evident the vacuum cleaner was a hot commodity with the increasing number of New York Times headliners on the subject.

Along with vacuum cleaners, consumers were also hooked on power. Americans became devoted to electric everything: can openers, lights, toothbrushes, knives, and much more. Americans continued to buy powered appliances from the same corporations, even as they provided fewer benefits (Strasser 2000, 84). Some technologies and household appliances did not work as effectively as marketed in advertisements. Freezers claimed to decrease shopping time by providing increased capacity (thus fewer trips). However, housewives only truly bought large amounts when they were on sale (Evans et al. 2001, 131). These new technologies and practices resulted in a habit of buying in excess. Betty Friedan, an American feminist writer, and activist wrote in 1963 “Why is it never said that the crucial function, the really important role that women serve as housewives is to buy more things for the house? (Fridean 1963, 299).

The 1950s was an era in which consumerism thrived and the consumer economy projected the power of American liberal democracy (608). Other countries tended to have other approaches and Europe specifically was naturally conservative in its philosophy of living (Whiteley 1987, 4). But after recovering economically from the war, Western Europe and Japan would quickly transition to mass consumerism as well. This American story would global: this was the onset of the Golden Age of what? Consumerism? In 1957, only 3 percent of Japanese households had an electric refrigerator, but by 1980 almost all households did (McNeill et al. 2014, 125). Countries began to embrace “Americanization, which according to environmental historians J.R. McNeill and Peter Engelke denoted “the high energy, materials-intensive American lifestyle, embodied in the automobile, household appliances, the freestanding house in the suburbs, and everyday consumer products” (McNeill et al. 2014 126).

Consuming became habitual all over the world. However, it was not always like this; consumer behavior was created. In the nineteenth century, companies and workers committed to a healthy balance of work and leisure. ‘Saint Monday’ (absenteeism) was well practiced, and workers would enjoy the privilege of having time off to relax and reset. Furthermore, practices of recycling were fundamental in the nineteenth century. In France during the 1860s, almost everything was reused: rags for paper, bone for tablets, buttons, phosphorus, and gelatin (Bonneuil et al., 2016). Recycling became embedded into society. Good housing keeping also minimized waste and several books came out during this time to teach the recycling of waste. However, entrepreneurs became to realize the profit behind consuming and the ability to create mass markets; in order for mass markets to create profit, they needed mass consumerism. Entrepreneurs now needed to enforce the idea of mass consumption upon consumers. “The explicit and paramount aim of politicians, industrialists, and advertisers alike was to create markets able to absorb the new productive capacities of Taylorist factories (Bonneuil et al., 2016, pg 154). While entrepreneurs began to make bigger profits, the environment was taking some of the costs.

The globalization of American consumerism had numerous unanticipated consequences. In the 1970s and 1980s, for instance, scientists discovered the refrigerants used in household appliances called “CFCs” (chlorofluorocarbons) were thinning the ozone layer. Household appliances were also various consumers of energy. Manufacturers combatted this issue by developing more efficient appliances (McNeill et al. 2014, 122). By 2002, they consumed on average 80 percent less energy than an appliance made in the 1980s (McNeill et al. 2014, 123). Nevertheless, as companies lowered energy use, more people continued to buy goods. As people accumulated more and more goods, it produced an enormous amount of waste. Consumers embraced the view that is it common and acceptable to discard products, even if simply to have a more up-to-date or appealing version (Whiteley 1987, 3). Any energy reduction was offset by increasing purchases and total energy consumption increased as a result. By (year) Fifteen percent of total electricity in China, for instance, was for refrigerators and household appliances. Consumerism, and its environmental consequences, had globalized (McNeill et al. 2014 124).

In part due to these patterns of increasing and wasteful consumption, the global economy threatened to outstrip ecological limits (McNeill et al. 124 134). Consumption affects the environment in multiple ways. In higher levels of production necessary to produce consumer appliances, which require large amounts of energy and material, large quantities of waste were produced as byproducts. On top of that, increased extraction and exploitation of natural resources, and waste damage on the environment accumulated. (Orecchia et al 2017, 1). An article by Jaia Syvistic, shows human energy expenditure since 1950 exceeds the energy expenditure across the entire prior 11,700 years of the Holocene (Elmqvist et al. 2021). . Resource demand influenced changes in population size, housing density, and consumption patterns (Elmqvist et al. 2021). In the years after the 1950s, hundreds of people around the globe began to attain levels of consumption unimaginable to their ancestors. The global economy’s effects on the planet became evident, and the economy was deeply reliant on the use of non-renewable resources such as fossil fuels and minerals.

While consumerism may have begun to thrive in the 1950s, the consumerism habit of postwar life continues to flourish today. As globalization and technological developments increase, the number of steps between people and the resources they use increases. This distance makes it progressively challenging for people to know and understand their consumptive decisions (Elmqvist et al. 2021). Ecosystem use is becoming commodified and commercialized. Small household appliances often have long supply chains associated with their production, and there is little transparency regarding the sustainability of any production process along the chain. It can be challenging, almost impossible to make positive choices for sustainable consumption with so many information steps within each step to understand or have information to inform consumption practices (Elmqvist et al. 2021).

It may seem that the vacuum cleaner is a simple, household appliance, but it is much more. It acts as a symbol of the beginning of an era of consumerism. An era that has deeply transformed our economy, environment, and everyday lives.

Creator

Sydney Hiatt

Source

Bonneuil, C., Jean-Baptiste Fressoz. “Phagocene: Consuming the Planet.” The Shock of The Anthropocene: The Earth, History, and US. Verso, London, 2016.

Bostwick, Louis, Frohardt, and Homer. Ace Vacuum Store - 115 North 16th Street. Photograph. Omaha, NE, July 22, 1948. The Durham Museum. https://durhammuseum.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15426coll1/id/45105/rec/1

Bostwick, Louis, Frohardt, and Homer. Sears, Roebuck, and Company. Photograph. The Durham Museum. Omaha, NE: The Durham Museum, November 18, 1931. The Durham

Museum. https://durhammuseum.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15426coll1/id/25254/rec/5.

Elmqvist, T., Andersson, E., McPhearson, T. et al. Urbanization in and for the Anthropocene. Urban Sustain 1, 6 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42949-021-00018-w

Evans, Mary, and Rosemary Pringle. “6: Women and Consumer Capitalism.” Essay. In Feminism: Critical Concepts in Literary and Cultural Studies 1, 1:124–43. Critical Concepts in Literary and Cultural Studies. London: Routledge, 2001.

Freidan, Betty. The Feminine Mystique. W.W Norton, 1963.

Gantz, Carroll. The Vacuum Cleaner. A History. Google Books. Jefferson: McFarland & Company Inc, 2012.https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Vacuum_Cleaner/NaV

Gk3HBUdkC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=when+was+the+kenmore+torpedo+vacuum+made&pg=PA125&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q=sears&f=false.

Glickman, Lawrence B. Consumer Society in American History. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1999.

Gonzalez, Cindy. “Omaha’s last Sears store, at the Crossroads, to close in March.” Omaha World-Herald. December 29, 2018, p. 2.

Hardy, Sheila M. A 1950s Housewife: Marriage and Homemaking in the 1950s. Google Books. Stroud, Gloucestershire, UK: The History Press, 2017.https://www.google.com

/books/edition/A1950s_Housewife/PA2VzgEACAAJ?hl=en&kptab=getbook.

Hiatt, Sydney. Image of Kenmore Commander Vacuum Cleaner. September 10, 2022.

Jackson, Kenneth T. Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of The United States. New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Kimball, Arthur G. “Sears-Roebuck and Regional Terms.” American Speech 38, no. 3 (1963): 209–13. https://doi.org/10.2307/454101.

McNeill, J.R, and Peter Engelke. The Great Acceleration: An Enviromental History of the Anthropocene since 1945. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: The Belknap

Press of Harvard University Press, 2014.

Mishkin, Frederic S. “The Household Balance Sheet and the Great Depression.” The Journal of Economic History 38, no. 4 (1978): 918-937. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2118664.

Nicolaides, Becky, and Andrew Wiese. "Suburbanization in the United States after 1945."

Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History. 26 Apr. 2017; Accessed 6 Oct. 2022. https://oxfordre.com/americanhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329

175.001.0001/acrefore-9780199329175-e-64.

Orecchia, C., Pietro Zoppoli. “Consumerism and environment: Does consumption behaviour affect environmental quality?” Institute for Studies and Economic Analyses, Rome.

November 2007.

Strasser, Susan. Never Done: A History of American Housework. Google Books. New York, NY: Henry Holt, 2000. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Never_Done/Qlb8O5zlxgY

C?hl=en&gbpv=0.

The Associated Press. “Sears, once world’s largest retailer, files for Chapter 11.” Omaha World Herald. October 16, 2018, p.2.

The Social History of the American Family: An Encyclopedia. United States: SAGE Publications, 2014.

Whiteley, Nigel. “Toward a Throw-Away Culture. Consumerism, ‘Style Obsolescence’ and Cultural Theory in the 1950s and 1960s.” Oxford Art Journal 10, no. 2 (1987): 327. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1360444.

“Vacuum Sales At Record: Dealing in Household Cleaners Already Top Prewar High.” The New York Times, August 13, 1949. https://www.nytimes.com/1949/08/13/archives/vacuum-sales-at-record-dealings-in-household-cleaners-already-top.html?url=http%3A%2F%2Ftimesmachine.nytimes.com%2Ftimesmachine%2F1949%2F08%2F13%2F96469776.html%3FpageNumber%3D33.

“Vacuum Cleaner Sales: 15.8 Per Cent Increase in First Six Months of 1950 Reported.” The New York Times, July 21, 1950. https://www.nytimes.com/1950/07/21/archives/vacuum-cleaner-sales-158-per-cent-increase-in-first-six-months-of.html?url=http%3A%2F%2Ftimesmachine.nytimes.com%2Ftimesmachine%2F1950%2F07%2F21%2F113167016.html%3FpageNumber%3D33.

“Vacuum Cleaner Sales Rise.” The New York Times, October 26, 1954. https://www.nytimes.com/1954/10/26/archives/vacuum-cleaner-salerise.html?url=http%3A%2F%2Ftimesmachine.nytimes.com%2Ftimesmachine%2F1954%2F10%2F26%2F86790944.html%3FpageNumber%3D44.

Bostwick, Louis, Frohardt, and Homer. Ace Vacuum Store - 115 North 16th Street. Photograph. Omaha, NE, July 22, 1948. The Durham Museum. https://durhammuseum.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15426coll1/id/45105/rec/1

Bostwick, Louis, Frohardt, and Homer. Sears, Roebuck, and Company. Photograph. The Durham Museum. Omaha, NE: The Durham Museum, November 18, 1931. The Durham

Museum. https://durhammuseum.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15426coll1/id/25254/rec/5.

Elmqvist, T., Andersson, E., McPhearson, T. et al. Urbanization in and for the Anthropocene. Urban Sustain 1, 6 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42949-021-00018-w

Evans, Mary, and Rosemary Pringle. “6: Women and Consumer Capitalism.” Essay. In Feminism: Critical Concepts in Literary and Cultural Studies 1, 1:124–43. Critical Concepts in Literary and Cultural Studies. London: Routledge, 2001.

Freidan, Betty. The Feminine Mystique. W.W Norton, 1963.

Gantz, Carroll. The Vacuum Cleaner. A History. Google Books. Jefferson: McFarland & Company Inc, 2012.https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Vacuum_Cleaner/NaV

Gk3HBUdkC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=when+was+the+kenmore+torpedo+vacuum+made&pg=PA125&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q=sears&f=false.

Glickman, Lawrence B. Consumer Society in American History. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1999.

Gonzalez, Cindy. “Omaha’s last Sears store, at the Crossroads, to close in March.” Omaha World-Herald. December 29, 2018, p. 2.

Hardy, Sheila M. A 1950s Housewife: Marriage and Homemaking in the 1950s. Google Books. Stroud, Gloucestershire, UK: The History Press, 2017.https://www.google.com

/books/edition/A1950s_Housewife/PA2VzgEACAAJ?hl=en&kptab=getbook.

Hiatt, Sydney. Image of Kenmore Commander Vacuum Cleaner. September 10, 2022.

Jackson, Kenneth T. Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of The United States. New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Kimball, Arthur G. “Sears-Roebuck and Regional Terms.” American Speech 38, no. 3 (1963): 209–13. https://doi.org/10.2307/454101.

McNeill, J.R, and Peter Engelke. The Great Acceleration: An Enviromental History of the Anthropocene since 1945. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: The Belknap

Press of Harvard University Press, 2014.

Mishkin, Frederic S. “The Household Balance Sheet and the Great Depression.” The Journal of Economic History 38, no. 4 (1978): 918-937. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2118664.

Nicolaides, Becky, and Andrew Wiese. "Suburbanization in the United States after 1945."

Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History. 26 Apr. 2017; Accessed 6 Oct. 2022. https://oxfordre.com/americanhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329

175.001.0001/acrefore-9780199329175-e-64.

Orecchia, C., Pietro Zoppoli. “Consumerism and environment: Does consumption behaviour affect environmental quality?” Institute for Studies and Economic Analyses, Rome.

November 2007.

Strasser, Susan. Never Done: A History of American Housework. Google Books. New York, NY: Henry Holt, 2000. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Never_Done/Qlb8O5zlxgY

C?hl=en&gbpv=0.

The Associated Press. “Sears, once world’s largest retailer, files for Chapter 11.” Omaha World Herald. October 16, 2018, p.2.

The Social History of the American Family: An Encyclopedia. United States: SAGE Publications, 2014.

Whiteley, Nigel. “Toward a Throw-Away Culture. Consumerism, ‘Style Obsolescence’ and Cultural Theory in the 1950s and 1960s.” Oxford Art Journal 10, no. 2 (1987): 327. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1360444.

“Vacuum Sales At Record: Dealing in Household Cleaners Already Top Prewar High.” The New York Times, August 13, 1949. https://www.nytimes.com/1949/08/13/archives/vacuum-sales-at-record-dealings-in-household-cleaners-already-top.html?url=http%3A%2F%2Ftimesmachine.nytimes.com%2Ftimesmachine%2F1949%2F08%2F13%2F96469776.html%3FpageNumber%3D33.

“Vacuum Cleaner Sales: 15.8 Per Cent Increase in First Six Months of 1950 Reported.” The New York Times, July 21, 1950. https://www.nytimes.com/1950/07/21/archives/vacuum-cleaner-sales-158-per-cent-increase-in-first-six-months-of.html?url=http%3A%2F%2Ftimesmachine.nytimes.com%2Ftimesmachine%2F1950%2F07%2F21%2F113167016.html%3FpageNumber%3D33.

“Vacuum Cleaner Sales Rise.” The New York Times, October 26, 1954. https://www.nytimes.com/1954/10/26/archives/vacuum-cleaner-salerise.html?url=http%3A%2F%2Ftimesmachine.nytimes.com%2Ftimesmachine%2F1954%2F10%2F26%2F86790944.html%3FpageNumber%3D44.

Rights

The Durham Museum Permanent Collection

Collection

Citation

Sydney Hiatt, “Vacuum Cleaner,” Omaha in the Anthropocene, accessed May 6, 2024, https://steppingintothemap.com/anthropocene/items/show/46.

Embed

Copy the code below into your web page