Tea Tin

Title

Tea Tin

Subject

Tea is one of the oldest drinks on Earth. According to Chinese legend, emperor Shen Nung discovered tea. In the following centuries, tea spread to every populated continent through global trade. The silk road was a common route used. Due to high demand, plantations mass produced tea in the late nineteenth century. This ignited the plantationocene. The plantationocene is the global and local effect plantations have on the environment and communities. It has decreased biodiversity and often exploits workers. In the early twentieth century, mass transportation helped connect goods with the public. Tea culture made its way from Chicago to Omaha through the Union Pacific Railroad. Union Pacific's headquarters are in Omaha. Various products, like tea, were connected by the wide access to industrial transportation. As the world adapts to global products and cultures, an impact continues to be made on the earth’s climate and ecosystems.

Description

In China, tea is said to be a gift from the Great Mother Goddess herself. It is supposed to bring health and longevity to the drinker. Tea is one of the oldest drinks on Earth, and its popularity has lasted to the modern day. Longevity could be said to be the beverage’s preeminent historical characteristic. Today, almost every culture has its own variety of tea. Cultural and social rituals surrounding the cultivating, preparing, and drinking of tea mirror human diversity. From Japanese tea ceremonies to British High Tea, the tea leaf sunk its teeth into globalized society hundreds of years ago and has not let go. Much can (and has) been said about the rich cultural and even spiritual significance of tea, but as with so many global commodities, the story is complex. Its elevation to a beverage of global significance has come with immense ecological and social costs that extend to the present. Tea connects China to Omaha, NE, and everywhere in between. The tea once contained in the canister held in The Durham Museum collection was a long way from its home, but the artifact is a reminder of the journey from seed, to plantation, to train, to cup. Tea has a deep connection to the plantationocene, which is the global and local effect plantations have on the environment and communities.

As one of the many legends have it, tea was discovered by a Chinese healer and emperor, Shen Nung in the year 2732 (Hohenegger, 2006). He and his traveling party were taking a rest from a long journey, and they needed to boil water to ensure its drinking safety. All of a sudden, leaves from a nearby tea bush landed in the pot. Ever inquisitive, Shen Nung took a sip and was delighted with the taste. He had just had the first sip of tea. (Hohenegger, 2006) This is one of many stories of the origin of tea, and many others emphasize tea’s stimulative or healing properties. The rich green of the tea plant held spiritual significance for some. It was a “good color” that would bring health and longevity to its consumer. Tea also had practical appeal. Chinese monks drank tea to stay awake during long hours of meditation (Hohenegger, 2006). Nomads dried and compressed leaves from the tea bush into solid bricks. It became an easily transportable and nutritious drink for mobile societies.

Tea became an object of intrinsic value as well; traders used tea as currency from China to Russia. (Pomeranz, 2006) The plant Camellia sinensis, or the tea bush, is native to southern China, Thailand, Myanmar, Laos, and northeastern India. (Xiao 2016) We will never know the national identity of the person who actually brewed the first cup of tea, but written accounts place its origin in the southwest of China. These are also the regions where agriculturalists allegedly transformed the wild plant into a agriculture crop. Regardless of its exact origin, tea was an incredibly valued resource in ancient China, both for its people’s consumption, and for consumption elsewhere. In the Tang Dynasty (618-906), tea was made the national drink of China and the already popular drink sunk its teeth even deeper into Chinese society. To satisfy the high demand, farmers replaced preexisting ecologies with fields of tea bushes. Eventually, farmers shifted from foraging to cultivating the plants to maximize output. (Zhong 2010) By year, tea was a mass agricultural crop. The Tea-horse Road was instrumental in the commerce of tea in ancient China, beginning in the Tang dynasty (Pang 2022). Consisting of two major paths in the neighboring Sichuan and Yunnan southwestern areas of China, this road connected Tibetan markets with central China, and was a central route in tea trade. Many towns and shrines were erected along this route, as commerce flowed through the towns regularly (2014). The popularity of tea stayed consistent. Even the Mongol invasion of China in years presented only a temporary reduction in volume (Perdue 2015). Tea eventually found its way off the mainland and into Japanese arms around the year 800 CE. (Varley 1989)

With its rise in popularity, tea plant farming practices shifted to meet higher demand. Traditional cultivators planted tea bushes in standing forests. These “tea gardens” were ecologically sustainable. This polyculture naturally repelled pests and nourished the soil (Qi 2013). In ancient China, as a result, tea cultivation required no mass deforestation. From ancient times into modern times, tea became an increasingly global product, however, these tea gardens became harder and harder to maintain locally.

Europeans discovered tea around the seventeenth century and have been hooked since. The Dutch East India Company pioneered this early trade, but European taste aesthetics did not yet favor the beverage (Rappaport 2019). Demand skyrocketed during the late eighteenth century when the British East India Company got involved. The British East India company conquered lands, enacted monopolies, and stimulated trade for much of the world (Pomeranz 2018). Tea entered the European markets as a medicinal product, but by the early 1800s, it became a British obsession (Rappaport 2019).

As British demand increased and its imperial dominion expanded, global demand for the leaf went up. Cultivation shifted again to meet this new demand. The tea bush grows in any tropic climate. The colonization of many new tropical British territories gave British businessmen new landscapes and populations to exploit. European export-oriented production favored plantation to mass produce tea (Dey 2021). Plantations favor monocultures which require the near or complete removal of indigenous ecosystems. The harmony of the tea garden was lost to capitalistic gains, but the people working the field also lost as well. The days of plantation workers are long and hard, and often the conditions of their work are brutal (Konings 2012). The larger implications of this system are communities that rely on one dominating company in the area, that could pull their support or funding at any second. This rise of plantations is the beginning of the Plantationocene, where the world started to significantly shift its means of food production to monocultures and mass produced products.

Eventually, tea made its way to America. In the eighteenth century, Dutch colonists established a tea ritual in the upper-class households of America. Tea symbolized wealth and tea consumption took on the trappings of class. Teapots, tea trays, and tea tables became symbols of conspicuous consumption. The US “opening” of Japan in 1859, established a stronger connection between Asia and America. When the United States initiated Japan to engage in trade with the West, U.S. tea merchants included Japanese green teas in their trade. According to Jane Pettigrew, by 1880, “47 percent of all tea imported by American tea traders came from Japan” (Pettigrew 2015).

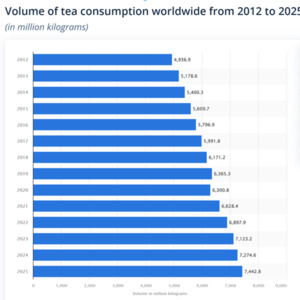

During the nineteenth century, consumers incorporated tea into American culture. “Afternoon tea” became popular and was often associated with the upper classes and casual company. (Pettigrew 2015) As the demand for tea in this growing country increased, more efficient methods of cultivation were required. Intercontinental trade supplies most of the tea consumed around the world. In the US, the majority of tea comes from China and India (Micheal 2021). Expansive shipping routes are used every day in order to make this trade possible.

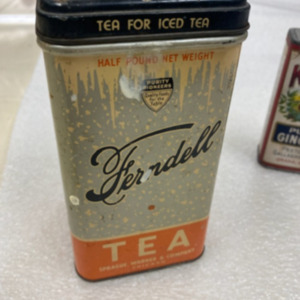

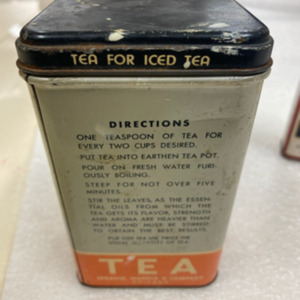

Our object of focus, the iced tea tin, was produced by Sprague Warner & Company. Located in Chicago, “this modern manufacturing, warehousing, and merchandising plant occupies the largest building in the world devoted to the production and sale of food supplies” (Chicagology 2003). This food distribution company had sold production in bulk of certain brands, that specialized in canned goods, spices, baking powder, jams and jellies, and more, such as Richelieu, Batavia, and Ferndell, in which Ferndell is the origin brand of our object of focus. That is quite the distance of travel from Chicago to Omaha. It is not certain, but it is possible that tea had made its way from the distribution center of Chicago down to the fields of Omaha through the Union Pacific Railroad. The Union Pacific railroad is a “freight-hauling railroad that operates 8,300 locomotives over 32,000 miles routes in 23 U.S. states west of Chicago and New Orleans” (Union Pacific). This provides accessibility for connections between the global supply chain, especially when it comes to crucial industries for survival, like the food industry. In fact, the Union Pacific Railroad has built and stationed its headquarters to be in Omaha, Nebraska. It would be reasonable to say that it is possible that the culture of tea had made its way to Omaha from Chicago through the Union Pacific Railroad, for this wide access to industrial transportation introduced other various foods to states around the country. The Union Pacific Railroad allowed for the interconnection of various cultures, which is why tea culture continues to spread around the world today, including Omaha.

As the world continues to adapt to the various cultures that communities all around the world have to offer, such as tea culture, this demonstrates that we are still living in the Anthropocene today. With these adaptations, humanity continues to make an impact on the world, on its climate, and on its ecosystems, for they are ever-changing. The introduction of new ideas of cultivation, such as plantation, is what allowed for the thriving of tea culture, especially in Omaha, where there are more tea cafes and shops surfacing as the years pass. Omaha is one of the more prominent cities in Nebraska that have taken a liking to the culture of tea, with other neighboring cities to soon follow. With the urbanization of cities all around, such as Omaha, many are still managing to transition to the customs of the other half of the world that are beneficial, therefore this could indicate that the Anthropocene is now.

As one of the many legends have it, tea was discovered by a Chinese healer and emperor, Shen Nung in the year 2732 (Hohenegger, 2006). He and his traveling party were taking a rest from a long journey, and they needed to boil water to ensure its drinking safety. All of a sudden, leaves from a nearby tea bush landed in the pot. Ever inquisitive, Shen Nung took a sip and was delighted with the taste. He had just had the first sip of tea. (Hohenegger, 2006) This is one of many stories of the origin of tea, and many others emphasize tea’s stimulative or healing properties. The rich green of the tea plant held spiritual significance for some. It was a “good color” that would bring health and longevity to its consumer. Tea also had practical appeal. Chinese monks drank tea to stay awake during long hours of meditation (Hohenegger, 2006). Nomads dried and compressed leaves from the tea bush into solid bricks. It became an easily transportable and nutritious drink for mobile societies.

Tea became an object of intrinsic value as well; traders used tea as currency from China to Russia. (Pomeranz, 2006) The plant Camellia sinensis, or the tea bush, is native to southern China, Thailand, Myanmar, Laos, and northeastern India. (Xiao 2016) We will never know the national identity of the person who actually brewed the first cup of tea, but written accounts place its origin in the southwest of China. These are also the regions where agriculturalists allegedly transformed the wild plant into a agriculture crop. Regardless of its exact origin, tea was an incredibly valued resource in ancient China, both for its people’s consumption, and for consumption elsewhere. In the Tang Dynasty (618-906), tea was made the national drink of China and the already popular drink sunk its teeth even deeper into Chinese society. To satisfy the high demand, farmers replaced preexisting ecologies with fields of tea bushes. Eventually, farmers shifted from foraging to cultivating the plants to maximize output. (Zhong 2010) By year, tea was a mass agricultural crop. The Tea-horse Road was instrumental in the commerce of tea in ancient China, beginning in the Tang dynasty (Pang 2022). Consisting of two major paths in the neighboring Sichuan and Yunnan southwestern areas of China, this road connected Tibetan markets with central China, and was a central route in tea trade. Many towns and shrines were erected along this route, as commerce flowed through the towns regularly (2014). The popularity of tea stayed consistent. Even the Mongol invasion of China in years presented only a temporary reduction in volume (Perdue 2015). Tea eventually found its way off the mainland and into Japanese arms around the year 800 CE. (Varley 1989)

With its rise in popularity, tea plant farming practices shifted to meet higher demand. Traditional cultivators planted tea bushes in standing forests. These “tea gardens” were ecologically sustainable. This polyculture naturally repelled pests and nourished the soil (Qi 2013). In ancient China, as a result, tea cultivation required no mass deforestation. From ancient times into modern times, tea became an increasingly global product, however, these tea gardens became harder and harder to maintain locally.

Europeans discovered tea around the seventeenth century and have been hooked since. The Dutch East India Company pioneered this early trade, but European taste aesthetics did not yet favor the beverage (Rappaport 2019). Demand skyrocketed during the late eighteenth century when the British East India Company got involved. The British East India company conquered lands, enacted monopolies, and stimulated trade for much of the world (Pomeranz 2018). Tea entered the European markets as a medicinal product, but by the early 1800s, it became a British obsession (Rappaport 2019).

As British demand increased and its imperial dominion expanded, global demand for the leaf went up. Cultivation shifted again to meet this new demand. The tea bush grows in any tropic climate. The colonization of many new tropical British territories gave British businessmen new landscapes and populations to exploit. European export-oriented production favored plantation to mass produce tea (Dey 2021). Plantations favor monocultures which require the near or complete removal of indigenous ecosystems. The harmony of the tea garden was lost to capitalistic gains, but the people working the field also lost as well. The days of plantation workers are long and hard, and often the conditions of their work are brutal (Konings 2012). The larger implications of this system are communities that rely on one dominating company in the area, that could pull their support or funding at any second. This rise of plantations is the beginning of the Plantationocene, where the world started to significantly shift its means of food production to monocultures and mass produced products.

Eventually, tea made its way to America. In the eighteenth century, Dutch colonists established a tea ritual in the upper-class households of America. Tea symbolized wealth and tea consumption took on the trappings of class. Teapots, tea trays, and tea tables became symbols of conspicuous consumption. The US “opening” of Japan in 1859, established a stronger connection between Asia and America. When the United States initiated Japan to engage in trade with the West, U.S. tea merchants included Japanese green teas in their trade. According to Jane Pettigrew, by 1880, “47 percent of all tea imported by American tea traders came from Japan” (Pettigrew 2015).

During the nineteenth century, consumers incorporated tea into American culture. “Afternoon tea” became popular and was often associated with the upper classes and casual company. (Pettigrew 2015) As the demand for tea in this growing country increased, more efficient methods of cultivation were required. Intercontinental trade supplies most of the tea consumed around the world. In the US, the majority of tea comes from China and India (Micheal 2021). Expansive shipping routes are used every day in order to make this trade possible.

Our object of focus, the iced tea tin, was produced by Sprague Warner & Company. Located in Chicago, “this modern manufacturing, warehousing, and merchandising plant occupies the largest building in the world devoted to the production and sale of food supplies” (Chicagology 2003). This food distribution company had sold production in bulk of certain brands, that specialized in canned goods, spices, baking powder, jams and jellies, and more, such as Richelieu, Batavia, and Ferndell, in which Ferndell is the origin brand of our object of focus. That is quite the distance of travel from Chicago to Omaha. It is not certain, but it is possible that tea had made its way from the distribution center of Chicago down to the fields of Omaha through the Union Pacific Railroad. The Union Pacific railroad is a “freight-hauling railroad that operates 8,300 locomotives over 32,000 miles routes in 23 U.S. states west of Chicago and New Orleans” (Union Pacific). This provides accessibility for connections between the global supply chain, especially when it comes to crucial industries for survival, like the food industry. In fact, the Union Pacific Railroad has built and stationed its headquarters to be in Omaha, Nebraska. It would be reasonable to say that it is possible that the culture of tea had made its way to Omaha from Chicago through the Union Pacific Railroad, for this wide access to industrial transportation introduced other various foods to states around the country. The Union Pacific Railroad allowed for the interconnection of various cultures, which is why tea culture continues to spread around the world today, including Omaha.

As the world continues to adapt to the various cultures that communities all around the world have to offer, such as tea culture, this demonstrates that we are still living in the Anthropocene today. With these adaptations, humanity continues to make an impact on the world, on its climate, and on its ecosystems, for they are ever-changing. The introduction of new ideas of cultivation, such as plantation, is what allowed for the thriving of tea culture, especially in Omaha, where there are more tea cafes and shops surfacing as the years pass. Omaha is one of the more prominent cities in Nebraska that have taken a liking to the culture of tea, with other neighboring cities to soon follow. With the urbanization of cities all around, such as Omaha, many are still managing to transition to the customs of the other half of the world that are beneficial, therefore this could indicate that the Anthropocene is now.

Source

Anderson, James. 2009. “China’s Southwestern Silk Road in World History.” University of Illinois Press. Accessed November 2, 2022. https://libres.uncg.edu/ir/uncg/f/J_Anderson_China_2009.pdf

Behal, Rana P. “Power Structure, Discipline and Labour in Assam Tea Plantations during Colonial Rule.” India's Labouring Poor, 2007, 143–72. https://doi.org/10.1017/upo9788175968349.008.

Chicagology. 2003. “Sprague Warner & Co. Warehouse.” Chicagology. Accessed November 2, 2022. https://chicagology.com/skyscrapers/skyscrapers040/

Dey, Arnab. “Bugs in the Garden: Tea Plantations and Environmental Constraints in Eastern India (Assam), 1840-1910.” Environment and History 21, no. 4 (2015): 537–65. https://doi.org/10.3197/096734015x14414683716235.

Dey, Arnab. Tea Environments and Plantation Culture: Imperial Disarray in Eastern India. CAMBRIDGE UNIV PRESS, 2021.

Gunathilaka, R.P. 2016. “The tea industry and a review of its price modeling in major tea producing countries.” Journal of Management and Strategy. Accessed November 1, 2022. doi:10.5430/jms.v7n1p21

Hohenegger, Beatrice. Liquid Jade: The Story of Tea from East to West. New York, New York: St. Martin's Press, 2006.

Konings, Piet. Gender and Plantation Labour in Africa: The Story of Tea Pluckers' Struggles in Cameroon. Bamenda, Cameroon: Langaa groupe d'intiative commune en recherche et publication, 2012.

Pettigrew, Jane. 2015. “The Evolution of American Tea Culture.” Teforia. Accessed November 1, 2022.

https://medium.com/@teforia/the-evolution-of-american-tea-culture-e4e3d493f7c

9#:~:text=Tea%20was%20introduced%20to%20America,to%20become%20the%20city's%20governor.

Pang, Kelly. “The Ancient Tea Horse Road.” Chinese Ancinet Tea-Horse Road, Discover the Ancient Tea Horse Route in China, 4 Jan. 2022, https://www.chinahighlights.com/travelguide/special-report/tea-horse-road/.

Perdue, Peter C. “Tea, Cloth, Gold, and Religion: Manchu Sources on Trade Missions from Mongolia to Tibet.” Late Imperial China, vol. 36, no. 2, 2015, pp. 1–22., https://doi.org/10.1353/late.2015.0005.

Pomeranz, Kenneth, and Steven Topik. The World That Trade Created: Society, Culture and the World Economy: 1400 to the Present. Routledge, 2018.

Published by Statista Research Department, and Jul 27. “Global: Annual Tea Consumption 2012-2025.” Statista, July 27, 2022. https://www.statista.com/statistics/940102/global-tea-consumption/.

Qi, Dan-Hui, Hui-Jun Guo, and Cai-Yu Sheng. “Assessment of Plant Species Diversity of Ancient Tea Garden Communities in Yunnan, Southwest of China.” Agroforestry Systems 87, no. 2 (2012): 465–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-012-9567-8.

Rappaport, Erika Diane. A Thirst for Empire: How Tea Shaped the Modern World. Princeton University Press, 2019.

Spengler, Robert N. Fruit from the Sands: The Silk Road Origins of the Foods We Eat. Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2020.

S. S, Sumesh, and Nitish Gogoi. “A Journey beyond Colonial History: Coolies in the Making of an ‘Adivasi Identity’ in Assam.” Labor History 62, no. 2 (2021): 134–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/0023656x.2021.1877263.

“Tea Plant – Camellia Sinensis.” Science Learning Hub. Accessed December 9, 2022. https://www.sciencelearn.org.nz/images/2040-tea-plant-camellia-sinensis.

The Tea and Horse Trade with Inner Asia during the Ming.” From Yuan to Modern China and Mongolia, 2014, 59–88. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004285293_005.

Union Pacific. “Company Overview.” Union Pacific. Accessed November 2, 2022. https://www.up.com/aboutup/corporate_info/uprrover/index.htm

Varley, Paul, editor. Tea in Japan. University of Hawaii Press, 1989.

Warner, Mason. 1912. “Sprague, Warner & Company, incorporated.” Sprague, Warner & Co. Accessed November 2, 2022.

https://archive.org/stream/spraguewarnercom00warn/spraguewarnercom00warn_djvu.txt

Xiao, Yan. 2016. “Study on Industrialization Prospects of the Silk Road Tea Culture.” Atlantis Press. Accessed November 1, 2022. doi: 10.2991/msetasse-16.2016.407.

Xiong, Yuan, Qianwen Kang, Weiheng Xu, Shaodong Huang, Fei Dai, Leiguang Wang, Ning Lu, and Weili Kou. “The Dynamics of Tea Plantation Encroachment into Forests and Effect on Forest Landscape Pattern during 1991–2021 through Time Series Landsat Images.” Ecological Indicators 141 (2022): 109132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2022.109132.

Xiao, Yan, and Zhaoyu Liao. “Study on Industrialization Prospects of the Silk Road Tea Culture.” Proceedings of the 2016 4th International Conference on Management Science, Education Technology, Arts, Social Science and Economics (msetasse-16), 2016. https://doi.org/10.2991/msetasse-16.2016.407.

Zhong, Weimin. 2010. “The roles of tea and opium in early economic globalization: A perspective on China’s crisis in the 19th century.” Frontiers of History in China. Accessed November 2, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11462-010-0004-0

Behal, Rana P. “Power Structure, Discipline and Labour in Assam Tea Plantations during Colonial Rule.” India's Labouring Poor, 2007, 143–72. https://doi.org/10.1017/upo9788175968349.008.

Chicagology. 2003. “Sprague Warner & Co. Warehouse.” Chicagology. Accessed November 2, 2022. https://chicagology.com/skyscrapers/skyscrapers040/

Dey, Arnab. “Bugs in the Garden: Tea Plantations and Environmental Constraints in Eastern India (Assam), 1840-1910.” Environment and History 21, no. 4 (2015): 537–65. https://doi.org/10.3197/096734015x14414683716235.

Dey, Arnab. Tea Environments and Plantation Culture: Imperial Disarray in Eastern India. CAMBRIDGE UNIV PRESS, 2021.

Gunathilaka, R.P. 2016. “The tea industry and a review of its price modeling in major tea producing countries.” Journal of Management and Strategy. Accessed November 1, 2022. doi:10.5430/jms.v7n1p21

Hohenegger, Beatrice. Liquid Jade: The Story of Tea from East to West. New York, New York: St. Martin's Press, 2006.

Konings, Piet. Gender and Plantation Labour in Africa: The Story of Tea Pluckers' Struggles in Cameroon. Bamenda, Cameroon: Langaa groupe d'intiative commune en recherche et publication, 2012.

Pettigrew, Jane. 2015. “The Evolution of American Tea Culture.” Teforia. Accessed November 1, 2022.

https://medium.com/@teforia/the-evolution-of-american-tea-culture-e4e3d493f7c

9#:~:text=Tea%20was%20introduced%20to%20America,to%20become%20the%20city's%20governor.

Pang, Kelly. “The Ancient Tea Horse Road.” Chinese Ancinet Tea-Horse Road, Discover the Ancient Tea Horse Route in China, 4 Jan. 2022, https://www.chinahighlights.com/travelguide/special-report/tea-horse-road/.

Perdue, Peter C. “Tea, Cloth, Gold, and Religion: Manchu Sources on Trade Missions from Mongolia to Tibet.” Late Imperial China, vol. 36, no. 2, 2015, pp. 1–22., https://doi.org/10.1353/late.2015.0005.

Pomeranz, Kenneth, and Steven Topik. The World That Trade Created: Society, Culture and the World Economy: 1400 to the Present. Routledge, 2018.

Published by Statista Research Department, and Jul 27. “Global: Annual Tea Consumption 2012-2025.” Statista, July 27, 2022. https://www.statista.com/statistics/940102/global-tea-consumption/.

Qi, Dan-Hui, Hui-Jun Guo, and Cai-Yu Sheng. “Assessment of Plant Species Diversity of Ancient Tea Garden Communities in Yunnan, Southwest of China.” Agroforestry Systems 87, no. 2 (2012): 465–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-012-9567-8.

Rappaport, Erika Diane. A Thirst for Empire: How Tea Shaped the Modern World. Princeton University Press, 2019.

Spengler, Robert N. Fruit from the Sands: The Silk Road Origins of the Foods We Eat. Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2020.

S. S, Sumesh, and Nitish Gogoi. “A Journey beyond Colonial History: Coolies in the Making of an ‘Adivasi Identity’ in Assam.” Labor History 62, no. 2 (2021): 134–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/0023656x.2021.1877263.

“Tea Plant – Camellia Sinensis.” Science Learning Hub. Accessed December 9, 2022. https://www.sciencelearn.org.nz/images/2040-tea-plant-camellia-sinensis.

The Tea and Horse Trade with Inner Asia during the Ming.” From Yuan to Modern China and Mongolia, 2014, 59–88. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004285293_005.

Union Pacific. “Company Overview.” Union Pacific. Accessed November 2, 2022. https://www.up.com/aboutup/corporate_info/uprrover/index.htm

Varley, Paul, editor. Tea in Japan. University of Hawaii Press, 1989.

Warner, Mason. 1912. “Sprague, Warner & Company, incorporated.” Sprague, Warner & Co. Accessed November 2, 2022.

https://archive.org/stream/spraguewarnercom00warn/spraguewarnercom00warn_djvu.txt

Xiao, Yan. 2016. “Study on Industrialization Prospects of the Silk Road Tea Culture.” Atlantis Press. Accessed November 1, 2022. doi: 10.2991/msetasse-16.2016.407.

Xiong, Yuan, Qianwen Kang, Weiheng Xu, Shaodong Huang, Fei Dai, Leiguang Wang, Ning Lu, and Weili Kou. “The Dynamics of Tea Plantation Encroachment into Forests and Effect on Forest Landscape Pattern during 1991–2021 through Time Series Landsat Images.” Ecological Indicators 141 (2022): 109132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2022.109132.

Xiao, Yan, and Zhaoyu Liao. “Study on Industrialization Prospects of the Silk Road Tea Culture.” Proceedings of the 2016 4th International Conference on Management Science, Education Technology, Arts, Social Science and Economics (msetasse-16), 2016. https://doi.org/10.2991/msetasse-16.2016.407.

Zhong, Weimin. 2010. “The roles of tea and opium in early economic globalization: A perspective on China’s crisis in the 19th century.” Frontiers of History in China. Accessed November 2, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11462-010-0004-0

Rights

The Durham Museum Permanent Collection

Collection

Citation

“Tea Tin,” Omaha in the Anthropocene, accessed May 8, 2024, https://steppingintothemap.com/anthropocene/items/show/48.

Embed

Copy the code below into your web page