Disease has been a constant scourge since humans have existed. As cities began to expand during the Industrial Revolution, the increasing population became a playground for disease. This was due in large part to dirty/contaminated water, overpopulation, and lack of proper sanitation.

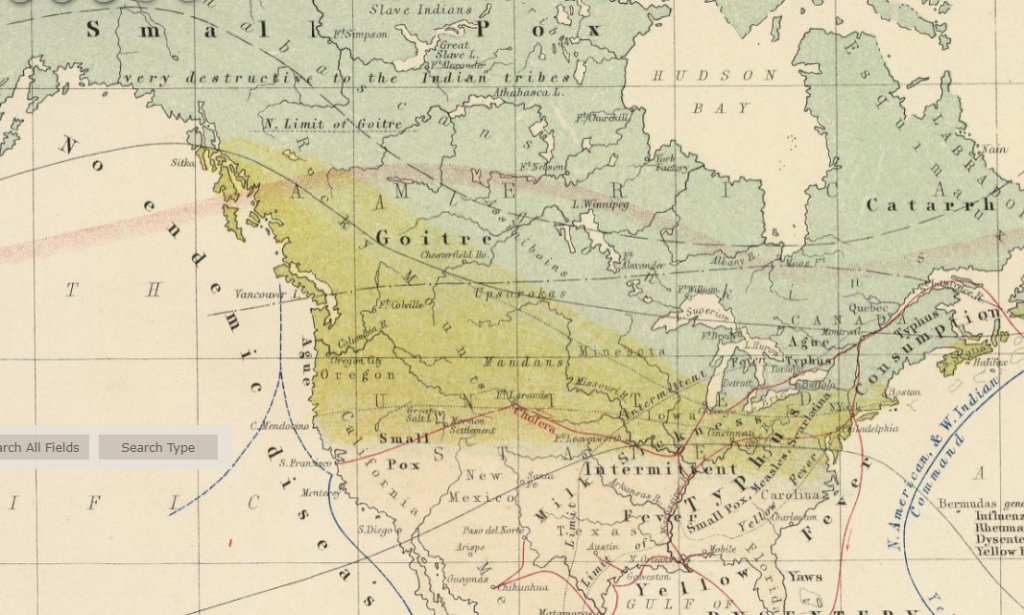

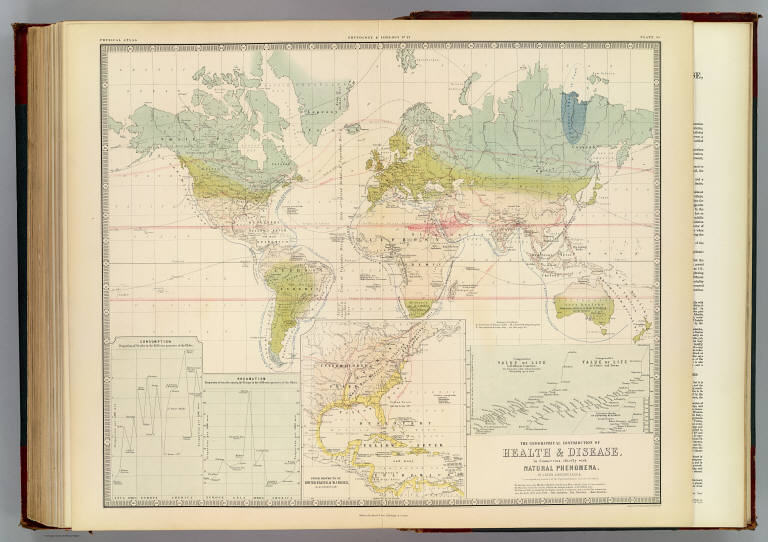

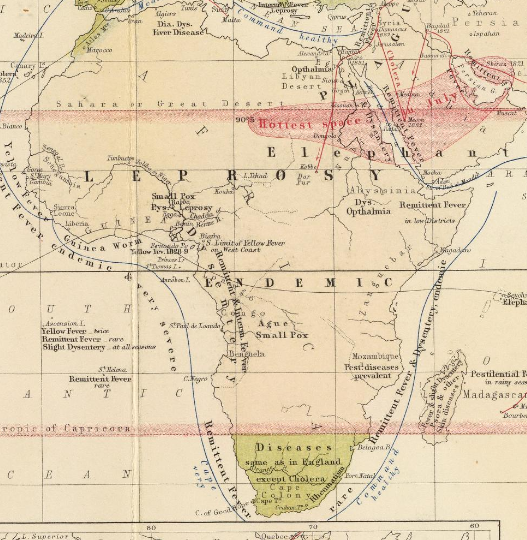

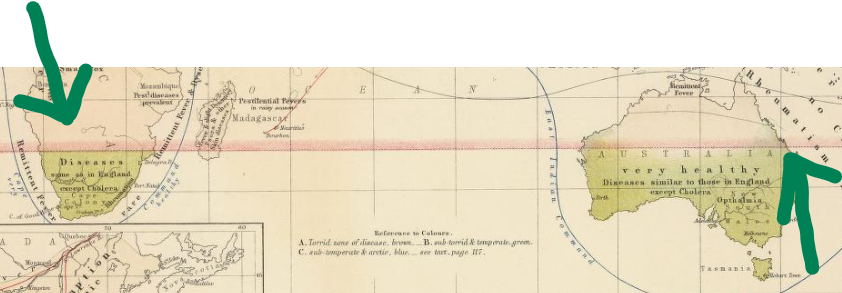

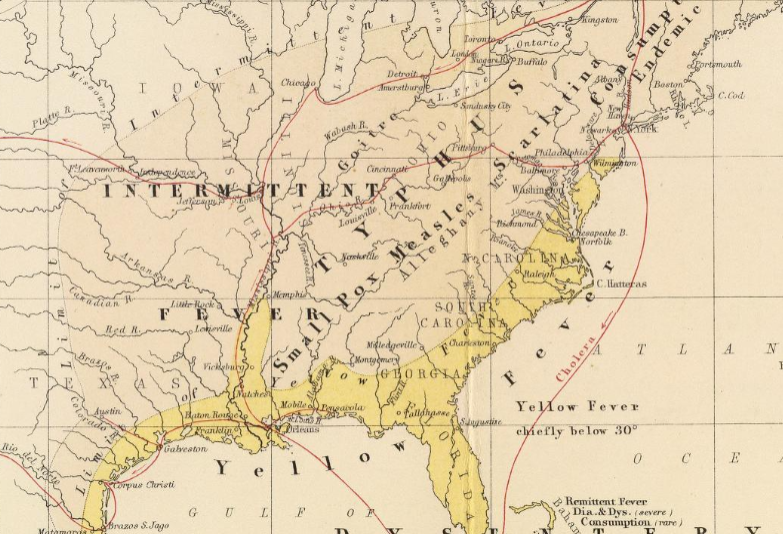

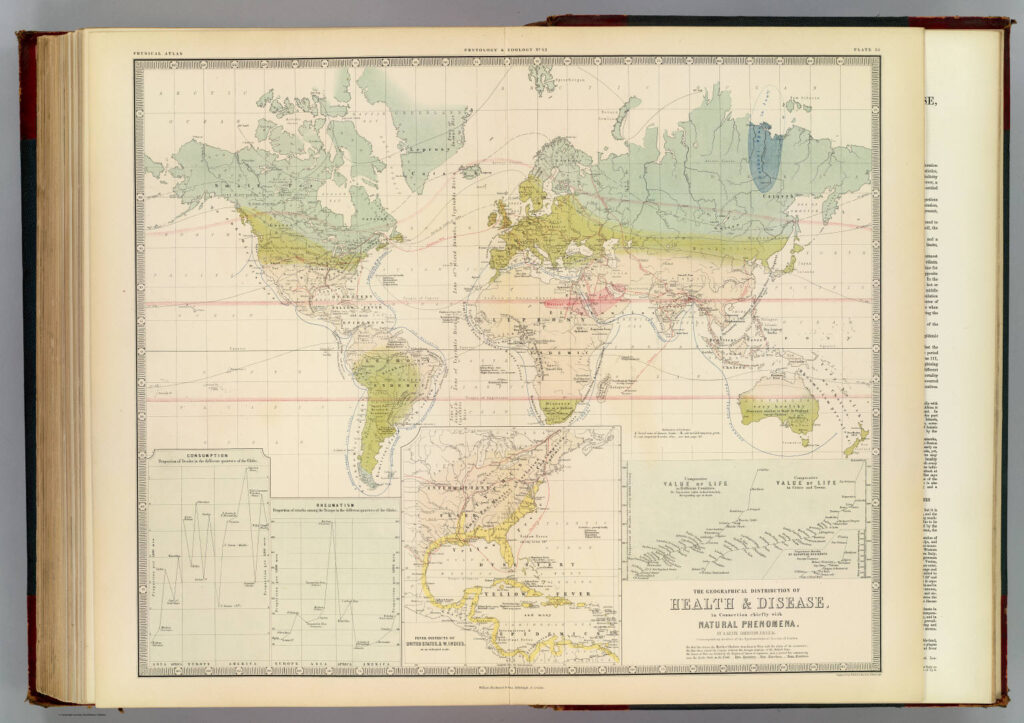

The first map I will break down is the map by Alexander Johnston titled “Geographical Distribution of Health and Disease in Connection Chiefly with Natural Phenomena.

First, the map is extremely detailed in mapping out the path of disease and its effects on populations. Second, the map is detailed in showing how disease spread during the 19th century and Industrial Revolution. At a time during poor safety and hygiene standards it was easy for sailors to fall ill and carry their illness with them to the areas where they were going to trade/sell their goods. However, the map shows that different diseases would affect different area for example; yellow fever and dysentery would effect the southern areas where there is a lot of intense heat and humidity. Cholera would begin in major cities/shipping points and be carried by shipping to other areas by infected people where it would travel through land routes. A final point of note about the map is that it provides statistics and stats on deaths from disease transmissions, showing just how devastating disease could be in the past.

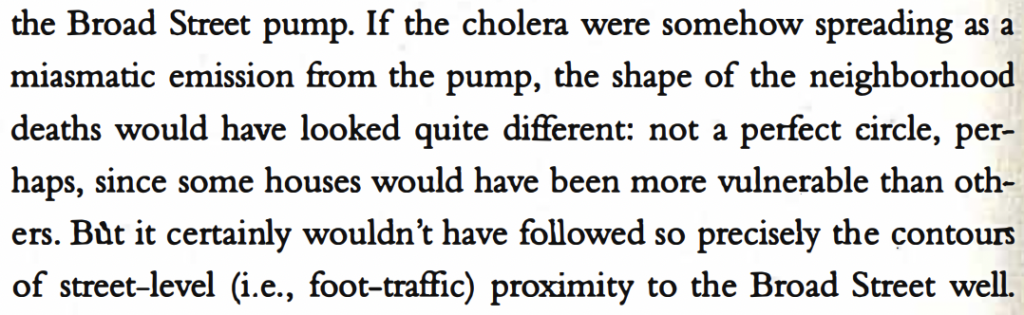

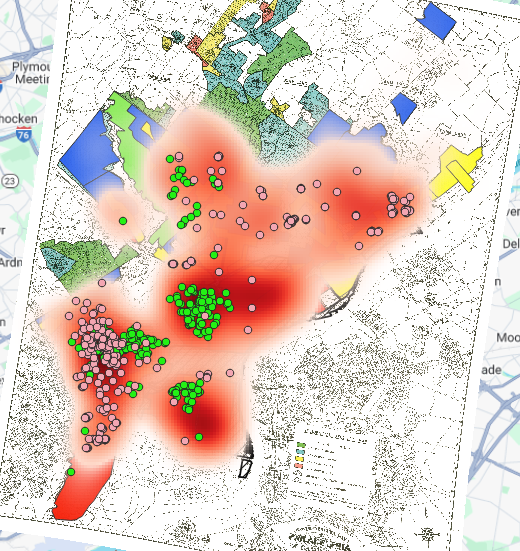

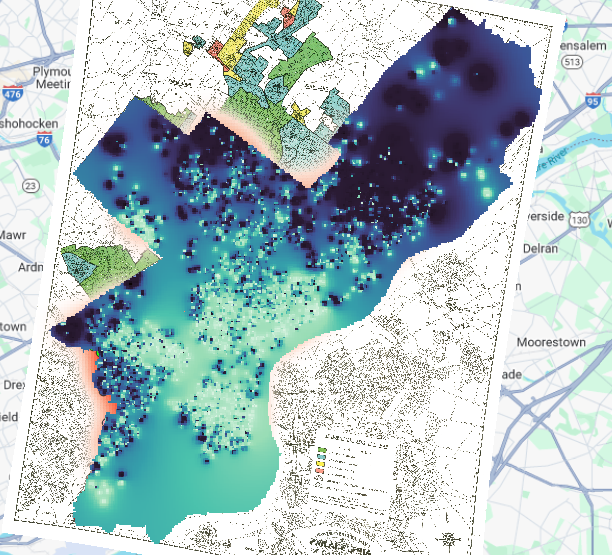

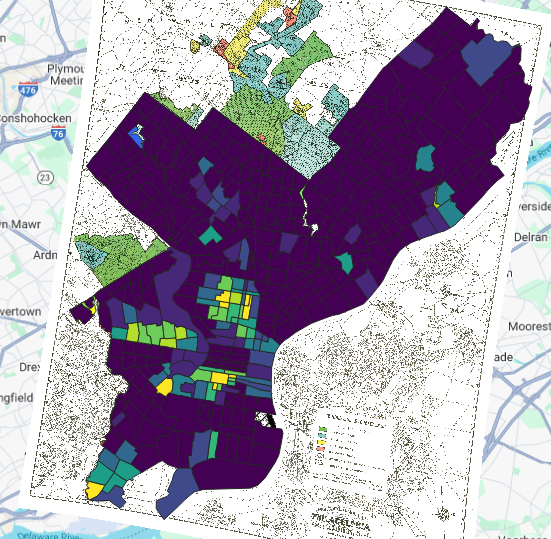

I will include in this section Steve Johnson’s “Ghost Map” and John Snow’s Cholera Map due to their overlap on the topic. As London’s population continued to increases during the 19th century a common scourge was cholera- a disease that spreads by dirty water. This disease would kill thousand during periods of outbreaks throughout London and large cities during the 19th century. At first, no one knew how or where this disease spread or infected other people, the prevailing thought was this “dirty-air/miasma theory of disease spread. That dirty air or rotting organic matter was the reason for why disease spread thought cities. It wasn’t until John Snow did extensive research into why cholera spread around London, his research began in West London. The research Snow found is detailed in the above map, Snow found that cholera was active in areas near water pumps. By taking this data, Snow found that Cholera transmits by contaminated water. Thus, his efforts increased hygiene measures to prevent people from falling ill and dying from the scourge of cholera.