Washing Machine

Title

Subject

Description

Imagine it is 1930 and there is a full load of laundry that needs to be washed. There are no automatic washing machines and the next two days are spend wringing and washing the clothes by hand. This process was referred to as “Blue Monday”, a tasking and daunting day in the early 1900s that was soon to be replaced by machines, detergents, and irons (Strasser, 1982). By the nineteen thirties, women’s roles began to change and households started to transfer out of labor-intensive chores, like doing laundry, to using items of convenience. One of these items was the washing machine, specifically, the PHILCO CORP model W5F9P non-automatic hand crank washing machine from the 1940s. (Figure I) The washing machine, in general, is a significant transitional artifact in Omaha’s social and environmental history. The washing machine acted as a catalyst that transformed societies, from individual homes to the global environment. The washing machine points to shifting gender roles in the home, social and economic changes associated with consumerism, and their unintended yet prominent environmental impacts lead to the Anthropocene.

The PHILCO CORP model W5F9P non-automatic hand crank washing machine is from a specific time period, the 1940s, however; the washing machine is a significant transitional object in global and environmental history. Laundry done prior to the 1930s was labor intensive and done by hand. Laundry in modern times uses convenient electric machines replacing human labor with electrical energy. This change in the way we do laundry was preceded by many transitional artifacts like the PHILCO CORP model W5F9P. This washing machine was non-automatic and hand crank, meaning that it required no electrical energy. It builds a bridge between the modern convince of washing clothes and the labor-intensive ways of the past making it a transitional object in the history of the washing machine. The washing machine, in general, represents the history in changing cultural norms that had significant global environmental impacts.

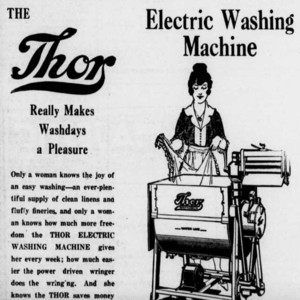

Prior to the invention of the washer machine, women would take hours to do a couple of loads of laundry. The phrase “wash day” was literal, a full day was needed to do laundry which consisted of keeping up with the demand of washing then ringing out the clothes then hanging and folding. The history of the washing machine dates back to 1797 and was called the Scrub Board, which was a simple wooden board. Since the invention of that wooden board, there has been a huge transition. The first sophisticated washing machine which was fully electric was created in 1908 by a company named Hurley Machine Company. This machine offered women more free time to do other house chores or spend more time with the family or even work, “making washing a spare time task instead of an all-day’s job” (Old Appliance Ads, 1910). The new and improved laundry machines allowed women to venture out to work.

Women were a central part of this story when it comes to the shift in the middle-class economics of families. The first and second wars were instrumental events that boosted the start of women branching away from their typical roles as housekeepers. During WWI women’s roles were starting to transform due to the new skills they learned. They were depended on by the men to keep the house running as well as to help with the food and textiles; “Women and girls washed the clothing of the officers and soldiers. They sewed and knitted coats, underwear, and socks” (Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute, 2018). At this time women were needed more than ever for their trade in textiles. With the progression of the war, the women were becoming more independent and thriving to do more outside of the house.

After the war, many women wanted to continue to work while other fell back into their typical roles of the house. “The middle class women continued to perform their traditional work but it was no longer considered real work, because unlike men, they earned no money… Cut off from the money economy, women might labor all day, producing all sorts of goods and service vital to the well being of the family and yet in the eyes of the world they did not work (Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute, 2018). Women in this time did not want to be housewives and were conflicted between staying at home with kids or with the house, and taking a good job. “The increase involvement in the workforce and education led to a change where the “excellence of the housewife” no longer depended on “spinning and weaving” skills (Strasser, 250).

The typical lifestyle was not suitable for most women anymore. In 1964, Modern Living Issue of the Omaha World Herald printed a spread called “Women at Work”. This article included a chart of potential part time jobs, an article about success, advice on when to look for a job and more. In one specific article by Alice Mulcahey, she explains that most women aren’t looking to just make money, but want something “challenging” that is stimulating and allows for recognition (Omaha World Herald, 1964). With new leisure time provided by new household items like the washing machine and being forced to give up jobs for men, women wanted education and work increasing family income after the war.

The end of World War II initiated a change in society that would eventually be known as the Consumer Revolution. American consumption is defined by a culture of new products with demand as well as new domestic habits at home (Strasser, 1989). The consumer revolution was not new but accelerated after World War II. After the war, car sales increased by 55%, sales of refrigerators by 164% and between 1939 and 1944, purchasing power for Americans rose by 60% (Bonneuil and Fressoz, 2017). The development and growth of a middle class of workers was dependent on their ambitions for betterment by purchasing power. Incomes may only rise if people start to buy more things, which depends on the rise of production of goods (U.S. Department of Labor, 1959). Post-war concerns like communism acted as a driver of consumerism as well by linking purchasing power to U.S. prosperity, civic duty and freedom. With the ability to buy now and purchase later using credit encouraged families to keep buying (ushistory.org, 2018). Before this time period, credit and loans were only given to big companies; but now was being used for houses, cars and items like washing machines. Consumer credit was a pillar of social control, where the increased workload was accepted in order to purchase more (Bonneuil and Fressoz, 2017). New methods of payment and increased production of goods led to the increase in consumption.

The Consumer Revolution led to greater purchasing power and consumption, but it also changed domestic habits. Although there was more to be produced, technological changes made it easier to produce more, with the same amount of works, in less time and for higher pay, freeing time for leisure for works (U.S. Department of Labor, 1959). From 1945 onward, working class benefited from the increase in wages but also an improving standard of living in addition to health insurance and pensions (Helgeson, 2016). The use of advertisement was a large part of consumerism and glorified consumption as a lifestyle. (Figure II) Ads made consumerism dissatisfied with their current products and ways of life. Advertisements contributed to consumption by changing social norms. Ads promoted deodorant for those who smell bad, mints or gum with bad breath and washing machines for women who spent hours handwashing clothes (Bonneuil and Fressoz, 2017). Families purchasing such items to make household chores easier freed up more time in addition to workers hours being cut. Advertisements and consumption created time and norms contributing to the social change seen with consumerism; this change also initiated environmental change.

The modern washing machine uses polluting sources of energy which are a major factor in climate change. The transitional artifact of the PHILCO CORP non-automatic washing machine developed into the automatic washing machines that we use today. These washing machines have now traded human labor for energy powered machines. The energy used in washing machines as well as other household appliances comes from power plants which burn fossil fuels to harvest energy (Steen, 2009). A by-product from the burning of fossil fuels is the release of greenhouse gases, most commonly CO2, into the atmosphere. Greenhouse gases are named as such because they stay in the atmosphere and trap heat on earth much like a greenhouse traps heat to keep plants warm (Steen, 2009). The use of energy demanding appliances like the washing machine is in part causing the planet to warm at an alarming rate which is having a detrimental effect on the global environment.

Energy demands have increased in Nebraska, the United States and across the globe partially due to households and their use of modern appliances. Nebraska is said to be one of the top ten states in the United States based on energy consumption (U.S. Energy Information Administration). This is due to new energy demanding farming technologies that have been developed over the past 100 years. One source explains the history of the evolution of U.S Energy Policy. In their article, they describe an increase in domestic energy uses since the 1980s (Fowler et. al., 2017). This energy demand can in part be explained by the use of modern appliances such as the washing machine. According to another source, the energy used by washing machines in today's time account for 6.4 percent of total residential electricity (Bao et. al., 2017). This shows that washing machines, like other modern appliances, demand energy from an already increasing energy trend. This phenomenon is not only seen in the U.S. but on a global scale as well. China has seen similar trends in energy demand. With their incremental population, China is attempting to reduce their carbon footprint by implementing household energy conservation ideologies (Sun et. al., 2018). Energy demands have increased both nationally and globally in part due to the use of modern appliances like the washing machine and these trends have an effect on the global story of the Anthropocene.

Though the story of the washing machine tells the American story of consumerism, it also tells a global story in the context of climate change and the Anthropocene. The Anthropocene is a new geological age in which humans have had a dominating effect on both the climate and the environment. With rising CO2 levels due to the emission of greenhouse gases and increased energy demands, the climate and environment are changing everywhere, not just in Omaha or the United States and have detrimental effects on the environment. Rising CO2 levels not only affect the atmosphere but leads to ocean acidification and species extinction (McNeil et. al., 2014) These emissions are also predicted to continue with an upward trajectory. The energy used by household items of convince, like the washing machine, come from power plants that burn fossil fuels. Stephen Davis and his team predict that these power plants are going to expand and increase their output of energy (Davis et. al., 2010). With the already rising CO2 levels due to fossil fuels and greenhouse gases, more power plants will only add to the environmental destruction. Today’s energy uses and their consequences show that humans are indeed altering both the climate and the environment on a global scale, leading to the Anthropocene.

The time of the Anthropocene has its roots in energy use, consumerism, and the great acceleration. One source says that the earth has a history itself, and this chapter has to do with the Anthropocene (Szerszynski). After World War II, two prominent events transpired: the population began to rise and consumption became more prominent. There were now more people in the world and with an optimistic consumer attitude these people bought more energy-intensive, convenient items such as the washing machine. J.R. McNeill and Peter Engelke discussed this trend in their book The Great Acceleration: An Environmental History of the Anthropocene saying, “Both these twin surges, of energy use and population growth, started in the eighteenth century and continue today...the Anthropocene, barring catastrophe, is set to continue. Human beings will go on exercising influence over the environments and over global ecology…” (McNeil et. al., 2014). Consumerism and the great acceleration, or population growth, both attributed to energy use and environmental crisis. Social change such as changing domestic norms and buying habits have influenced environmental changes such as the increase in energy usage, that has placed us in the geological time we know today as the Anthropocene.

The washing machine was a factor in local and global change. Domestic economies and social norms were reshaped through consumerism and with women entering the workforce, while the global environment has slowly deteriorated. The items of convenience like the washing machine have improved human life, while decreasing quality of the environment through increased energy usage. The washing machine shifted gender roles in society, reshaped local economies through consumerism, and had unintended yet prominent environmental impacts contributing to the new epoch, the Anthropocene.

Creator

Ellianne Jacques

Jordan Rogers

Source

Collection

Citation

Embed

Copy the code below into your web page