Omaha Horse Railway Bond

Title

Subject

In the late nineteenth century, the United States was well on its way to becoming an industrial, urban power. This transition did not happen overnight, though. Before people drove their cars to work, the horse-drawn streetcar was your only alternative to traveling by foot. It set the stage for the expansion of Omaha’s suburbs and the pollution produced by the people living in them.

Description

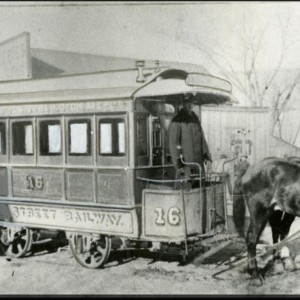

The emergence of the horse-drawn streetcar showcased the ingenious innovation of man in his quest to conquer time. The horse-drawn streetcar responded to the necessity for methods of intercity travel for people as populations continued to grow. The hybrid design of the horse-drawn streetcar combined the natural power of the horse with the industrial-age iron tracks. The establishment and expansion of the horse railway system in Omaha facilitated the city’s expansion. It was a bridge between animal and machine power that moved Omaha into an expanding industrial urbanized frontier. It ensured continuity and ease of travel to neighboring regions and communities. The Omaha Horse Railway was an archetypal organic machine representative of the world-altering impacts of industrial urbanization.

The horse-drawn railway reached the frontier Nebraska Territory in 1867. Prior to its arrival, the sleepy western gateway city was a frontier town barren of any timber, only miles of rolling hills and prairie grass. The city only had a few brick buildings and hugged the banks of the Missouri River (Hendee, 2015). The horse-drawn streetcar was nothing more than a omnibus on iron train tracks pulled by four horses. First introduced in New York in 1832 to serve the Harlem-New York City area (The Evening Post, 1833), its arrival in Omaha signaled the Nebraska territory had entered a new industrial age.

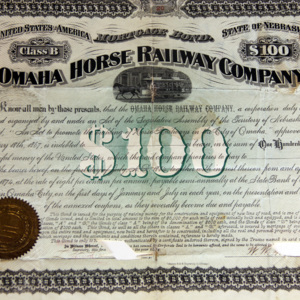

The entirety of the Omaha horse-drawn streetcar market would be dominated by the Omaha Horse Railway Company, chartered by the legislative assembly in 1867 (Martin, 1978). To help construct the foundations of the rail system, the Omaha Horse Railway Company introduced many incentives. Our object is a mortgage bond issued by the Omaha Horse Railway Company. (Figure I) The document is made of parchment and has smaller slips for the bond claims. The bond is valued at one hundred dollars with twenty slips that can be cut out in exchange for four dollars and accrued value at an established interest rate. (Figure II) The slips could be exchanged on two dates; the first of January and July each year. The mortgage bond on display is missing seven slips, indicating that the previous holder could have possibly already exchanged twenty-eight dollars. (Figure III) The bond also has information indicating that the Omaha Horse Railway Company was established through an act by the Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Nebraska on February 18th, 1867. The bond was issued in 1874 with the last exchange slip due in 1884. The bond can be exchanged at the Omaha office of the State Bank of Nebraska.

After being granted an ordinance by the Omaha City Council, construction on the rail tracks began. The first shovelful of earth to be removed was dug on Farnam Street and Ninth Street on November 13, 1868 (Martin, 1975). With the expansion and success of Union Pacific Railroad, Omaha was a growing frontier outpost and people flocked to the city. The city grew from 1,883 residents in 1860 to 102,555 residents in 1900 (Nebraska State Data Center, 2010), and the horse railway was a innovative method to help the growing city. Omaha was still relatively compact, however. At its inception, the horse railway operated from Ninth and Farnam Street―the heart of downtown― to Sixteenth Street and Capitol Avenue. Sixteenth Street was as far west as the track could go before the steep hills proved challenging for the horses (Thomas, 2017). To bypass this problematic terrain, the lines spread to serve North and South Omaha and avoided steep hills.

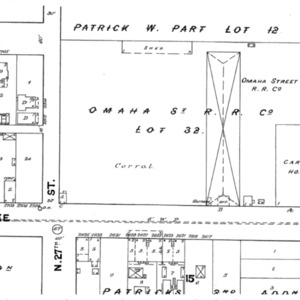

The potential benefits of having a street railroad system excited the population. Even before the groundbreaking took place on Ninth and Farnam, news that the tracks would run down 16th and 23rd streets were enough to get people to spring for prime real estate on the two streets (Martin, 1975). By the 1870s, the company had expanded its services to both North and South Omaha, running along 24th and 26th streets. But as the demand for services increased, particularly with the concentration of homes along the track lines, the company needed a maintenance shop to service the North Omaha area. In 1884, a barn was built on the corner of 24th and Lake Street, the barn consisted of a car shop, a corral, and shed. (Figure IV) The barn was so large it could stable 235 horses, enough to serve both North and South Omaha (Fletcher, n.d).

The horses are unique in that they are a living component of this system, finding themselves displaced from their natural habitats and domesticated for city transit. (Figure V) As such, they required basic maintenance and living requirements such as food and housing—resources that also came at the expense of the natural environment. It was estimated that to move one ton at 2.9 miles per hour along flat, paved terrain, a horse would require 3,421 calories of nutritional intake (McShane, 2007). Because the digestive systems of horses were able to metabolize and utilize low-quality grains, horses used within railway transportation were fed a diet of oats and hay. To meet the caloric approximations described, it was estimated that railway horses consumed anywhere between 13-20 pounds of oats and 8-12 pounds of hay per day.

Maintenance of horses were not their only downfall, however; horses were capable of transmitting disease and were eventually deemed financially inefficient, given the technological innovations that lie ahead of their time. The close compactness of cities made the spread for diseases easier. In 1872, the “Great Epizootic” struck Boston’s horse railway system leaving every horse either sick or deceased (Mohl, 1997). Alongside Boston, an estimated 80 percent of New York City’s horses suffered from disease, leaving large swaths of New Yorkers immobile (“The Horse Distemper”, 1872). By 1894, discussions held in New York concerned the issue of manure and its impact on public health, as it was estimated that its horse population exceeded 175,000 and was producing urine and manure at an uncontrollable rate (Morris, 2007). Urbanization accelerated, but there remained no clear separation between nature and culture.

The advent of horse drawn railway systems seemingly catalyzed human society’s urge to transform the natural landscape to accommodate the needs of the public. By paving roads and laying rails within them, Omaha and many other developing cities were able to impose man-made technologies upon what was once prairie or forest, comprised of vegetation, dirt and mud. Mud, in fact, proved itself to be a nuisance to early horse-drawn transportation methods; not only was traveling across natural terrain unclean, but was also energetically inefficient. By paving roads and establishing railway systems, horses and mules were able to carry loads at two to three times efficiency (McKee, 2014).

Omaha was not the only city however, to use the horse railway system. Expanding networks of horse railways emerged in cities across the United States and the world, from New York to San Francisco and Paris to Montevideo. Having a system in your city meant that you were entering the new industrial century. The horse railway system was first introduced in Nantes, France in 1826, quickly spreading to Paris and London by 1832. New York City got its first cars in 1828. By 1840, Boston, Philadelphia, and Baltimore all had established lines (Young, 2015). Another wave of expansion occurred in the 1860s, by the 1880s, almost 20,000 horse streetcars traveled on more than 30,000 miles of street railways across the United States (Young, 2015). Just as the horse railway helped Omaha to expand, other cities using it also grew. In Frankfort, Kentucky, which started its horse railway system in 1887, real-estate developers constantly lobbied for the streetcar line to reach the community of Bellepoint, originally left out of the route (Bogart, 1997). In San Francisco, old horse streetcars were converted into housing and formed the community of Cartown and even inspired a new type of housing architecture (Rhoads, 2000).

Expansion of the horse railway system was prominently notable in the United States compared to slower growth in Europe, where people called the technology the “American Railways” (Young, 2015). Which is ironic considering that the technology first appeared in Europe. Horse-drawn streetcars, and the rails they travelled on, began a process of redefining the meaning of city streets. This new definition would continue with the introduction of electric streetcars and automobiles (Young, 2015). Under this new understanding, the streets became “a place for mobility, diminishing the centrality of sociability, recreation, and other traditional street uses” (Young, 2015). The streets allowed for the connection of communities, in accordance with trends all over the United States, Omaha’s expansion was owed to the networks of its horse railway systems.

Intense demand for reliable intracity transportation allowed the Omaha Horse Railway Company to expand quickly. Homes popped up along the track lines, extending far out from downtown Omaha. However, as the city continued to grow, horse-drawn streetcars proved too slow from transporting people from the “streetcar suburbs” to their employer in the city. In 1887, the electric cable car was introduced by the Cable Tramway Company. Conflicts soon emerged between the two companies over operations and competition for tracks. Eventually the Omaha Horse Railway Company and the Cable Tramway Company merged to form the Omaha Street Railway Company in 1887 (Fletcher, n.d). With streetcars now operating completely on electric motors, which made the cars heavier, new tracks were required. Originally, 25-pounds “T” rails were laid for the horse tracks. After the merger and switch to electric, 45-pounds steel girder rails were required to accommodate the new cars (Thomson, 2014). The switch to electric streetcars marked and end to organic machines, horse-power now became horse-powered.

Given this myriad of environmental, health, financial issues facing horse-drawn transportation, it might seem that a transition toward electric cable cars was inevitable. This was not the case, however, in Benson, Nebraska. Omaha continued to grow between 1870 and 1900, and the suburban community of Benson was slowly on the rise. Seeing the success of the Omaha cable cars, the community established the Benson Motor Company in 1886, with cars pulled by steam-engines (Savage & Bell, 1894). The tracks ran on North 40th Street and Cuming Street, then connected to North 42nd and Hamilton, and finally following Military Road to North 58th Street (Fletcher, n.d). However, since most residents were still farmers, the loud noise proved to be a disturbance to the residents. The city soon declared it a nuisance and the company were forced to abandon their steam-powered engines and use horses to pull their cars (Savage and Bell, 1894).

The implementation of the horse-drawn streetcars had profound influence in the growth of the central city and linked it with suburban areas. Though operating for only a couple of years, it inspired new transportation innovations to connect the central city and its suburbs to nearby rural communities with a fast, frequent service not otherwise available before. This was evident when the City of Omaha annexed Benson on July 29th, 1917 (Persigehl, 2017). Horse drawn infrastructure laid the foundation in many American cities by the late 19th century for what was needed to establish a “cleaner”, more financially and energetically efficient mode of transit found in electric railway systems. Despite their difference in power methodology, horse-drawn, and electric streetcars served a common purpose - to enable to expansion of the growing communities in which they served, speeding up suburbanization and the settling of surrounding natural landscapes.

Urbanization was further developed through surrounding suburbanization and has both directly and indirectly impacted the Omaha area’s once natural landscape through road paving, construction of housing, businesses and infrastructure, and the collective pollution consequences coming as a result of consolidated human occupation and activity. Urbanization in Omaha was evident in the growth of the city between 1860 and 1900. Other cities around the world also saw a growth in their populations starting in the 1860s, when the horse railway system was expanding (Rees, 2016). Urbanization has contributed greatly to the Anthropocene as it required more extraction of natural resources to feed a growing, industrialized city. Materials were needed to build the horse railway lines and for horse care. Indirectly, through its facilitation of urbanization, materials were also needed to construct more homes and other amenities associated with a growing city (Awasthi, 1999). Perhaps the starkest impact associated with the Anthropocene, is the changing of the natural landscape. Grasslands and forests were soon replaced by gridded neighborhoods and paved lines connecting communities and cities (Rees, 2016).

These railways, both horse-drawn and eventually electric-powered, extended the reach of the city and allowed it to grow into what it is known as today—without these developments, growth may not have been seen until the invention, public access, and affordability of the automobile in the early 20th century. Accelerating the rate of suburbanization, the Omaha Horse Railway company also played a significant role in enabling the city’s contribution to worldwide pollution collectively derived from the necessity to transport, house, feed and accommodate growing populations. It is through this perspective that we understand how the intermediary method of human transport did more than get people home from work—it is one of many roots that ground the premise of worldwide geological and environmental scars inflicted by humankind.

Creator

Zak Phosri

Source

“A Statement of Facts―In Relation to the Origins, Progress and Prospect of the New York and Harlem Railroad Company.” The Evening Post. (1833, Feb 21). Retrieved from https://www.newspapers.com/clip/19998189/harlem_railroad_pt_1/

Awasthi, Aruna. (1999). “Environmental Degradation: A Case Study of Railways and Deforestation in India in The Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, 60, 572-581. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/44144125

Bogart, Charles H. (1997). “Frankfort’s Streetcars and Interurbans: The Bluegrass Route.” The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society. 95(4):395-424. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/23383835.

Fletcher, Adam. n.d. “26th and Lake Street Maintenance Shop.” North Omaha History. Retrieved from https://northomahahistory.com/2016/09/10/26th-and-lake-streetcar-barn/

Fletcher, Adam. n.d. “Benson Motor Company.” North Omaha History. Retrieved from https://northomahahistory.com/2017/03/04/benson-motor-company/

Hendee, David. (2015). “1865 in Omaha: A Momentous Year.” Omaha World-Herald. Retrieved from https://www.omaha.com/special_sections/in-omaha-a-momentous-year/article_72e950df-ec1f-53ae-b383-8ef47b8241fc.html.

Martin, Charles W. (1978). “Omaha in 1868-1869: Selections from the Letters of Joseph Barker,” Nebraska History. 59: 501-524.

McKee, Jim. (2014, Apr 6). “Horse Cars and Street Railway.” Retrieved from https://journalstar.com/news/local/jim-mckee-horse-cars-and-street-railways/article_09fc3864-c8f7-5f87-b033-ede68e26791f.html

McShane, Clay. “Transforming the Use of Urban Space: a Look at the Revolution in Street Pavements, 1880-1924.” Journal of Urban History, 1979, journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/009614427900500302?casa_token=_o0SYBpEa3gAAAAA:hXBVV7cIMPYnoDn4moKb5D2ryMj-HAWFwWgpOlk0RHeDwnQZIku-LceZMkjesKtvNZzFQIp4c1QK.

McShane, Clay and Joel A. Tarr. (2007). The Horse in the City: Living Machines in the Nineteenth Century. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Mohl, Raymond A. (1997). The Making of Urban America (2nd edition). Lanham, MD: SR Books.

Morris, E. (2007). From Horse Power to Horsepower. ACCESS Magazine, 1(30). Retrieved from https://cloudfront.escholarship.org/dist/prd/content/qt6sm968t2/qt6sm968t2.pdf.

Nebraska State Data Center, Center for Public Affairs Research, University of Nebraska at Omaha, and U.S Bureau of the Census. (2010). “Population of Nebraska Incorporated Places, 1860 to 1920.” Retrieved from https://opportunity.nebraska.gov/files/research/stathand/bsect5a.htm

Persigehl, Linda. (2017). “Battle for Benson: The 100th Anniversary of its Annexation.” Omaha Magazine. Retrieved from http://omahamagazine.com/articles/battle-for-benson/

Rees, Jonathan. (2016). “Industrialization and Urbanization in the United States, 1880-1929.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History. Retrieved from http://oxfordre.com/americanhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.001.0001/acrefore-9780199329175-e-327

Rhoads, William B. (2000). “The Machine in the Garden: The trolley Cottage as Romantic Artifact.” Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture. 8:17-32. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/3514405

Roberts, G. K., & Steadman, P. (1999). American Cities & Technology: Wilderness to Wired City. New York, NY: Routledge.

Savage, James W. and John T. Bell. (1894). History of the City of Omaha Nebraska. NYC, NY: Nunsell & Company.

Thavenet, Dennis. “A History of Omaha Public Transportation.” 1960, digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/1267.

“The Horse Distemper.” (1872, Oct 26) Retrieved from https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1872/10/26/83212943.pdf

Thomas, Doug. (2017, Dec 11). “Omaha’s Once-Sprawling Streetcar System Now Lives Only In Memory.” Retrived from https://www.omaha.com/living/omaha-s-once-sprawling-streetcar-system-now-lives-only-in/article_faf152c0-da05-11e7-b045-2f378c682fd5.html

Thompson, Joe. (2014). “Omaha Street Railway History - 1909 News Advertisements by William H. Hodge.” Cable Car Guy. Retrieved from http://www.cable-car-guy.com/html/ccomaha.html

Young, Jay. (2015). “Infrastructure: Mass Transit in 19th- and 20th-Century Urban America.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History. Retrieved from http://oxfordre.com/americanhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.001.0001/acrefore-9780199329175-e-28

Rights

Collection

Citation

Embed

Copy the code below into your web page