Center-pivot Irrigation

Title

Subject

Description

In 1950, the world’s population was 2.5 billion people. Today the population is over 7.6 billion and still rapidly growing. How did the world produce enough food to support this demographic exponentially growing population? Historians argue that the answer resides in changing agricultural practices and technology, termed agricultural revolutions[1]. The most recent agricultural revolution was industrial and the center-pivot irrigation system was one of its later developments. Developed by Nebraskan Frank Zybach in the early 1940s, the system brought about a great deal of change throughout the industry drastically affecting crop production by allowing more efficient crop irrigation in both old and new croplands. The system had unintended consequences, however, including the localized depletion of groundwater. In the US Midwest, this technology and the reshaping of agricultural practices it incentivized affected the High Plains aquifer. The center-pivot irrigation system is a crucial artifact in Omaha’s environmental history. (Figure I) It was developed in Nebraska and its impacts are now global in scope. Zybach and his development of the central-irrigation pivot improved farming efficiency and opened up vast dry land areas to cultivation, but it also created an unsustainable relationship between farmers and subsurface water. The global significance of this technology further defines the Anthropocene as an epoch that has been shaped by the hands of humanity.

The center-pivot irrigation system revolutionized the farming of crops around the world and enabled the world to grow crops at an unprecedented rate. However, before the advent of center-pivot irrigation, most farmers resorted to dry land farming while hoping for rain. Those who possessed land capable of being leveled and water beneath that land could irrigate with ditches or grated pipe (“First Pivots Installed” 2006). Still, dry years could cripple a farmer’s yields and lead to other disastrous events such as the Dust Bowl of the 1930s. Without a reliable source of water each season farmers could not depend on producing good yields. Other forms of irrigation were labor intensive and brought additional problems, such as gravity systems that failed to irrigate fields evenly. Therefore farmers desperately needed another option that was practical and produced results, results that the center-pivot could provide.

Throughout the 1940s, it became apparent dry land irrigation was reaching its limits. In Nebraska, the process of watering and fertilizing large fields involved hard labor and took time. It involved farmers disconnecting and reconnecting pipes in different areas to cover other areas of a field. Zybach’s great innovation was to speed up this process and reduce labor requirement. This system can be dated all the way back to the year 1948, when Frank Zybach built his very first prototype after being inspired to find a better solution to an exhausting task. He observed men connecting pieces of aluminum pipe to water a section of a field, and afterwards would disconnect all the pipes only to repeat the process again to irrigate another section of the field. He believed that there must be a better and more effective way to perform the same task, so he got to work on finding a way. In 1948 he finally produced his very first model of the system while living in Colorado, and only a year later in 1949, after continuing to perfect the design, he applied for a patent and it was granted in 1952.

With a series of long pipes joined together and supported above the ground by trusses mounted on wheels, the center-pivot system rotates around a fixed point to disperse water and fertilizers through sprinklers evenly spaced along the length of the pipes (McKnight 1979 ,123) (Figure 1). The central-pivot works its way around a field to form a complete circle, while often leaving the corners of the field unirrigated. It could quickly and efficiently irrigate an entire field within minutes, with early systems from the 1970s able to “pump 1,000 gallons of water a minute over a 160-acre section of corn” (Aucoin 1979, 19). In an entire day, “A center-pivot sprinkler system for a 160-acre field (130- 138 acres irrigated) when operating and pumping even at a minimal rate (about 560 gpm) withdraws as much water per day as a town of about 10,000 people (Hallberg 1976, 28). Zybach’s invention promised to more effectively irrigate fields in Nebraska and around the world, opening new environments for cultivation that were previously believed to be infertile.

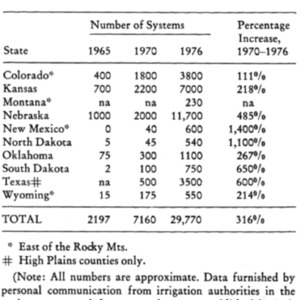

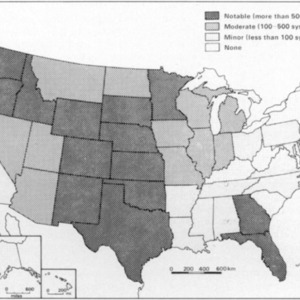

Zybach’s creation was a radical new design, and most people were rather reluctant to incorporate the system into their own fields. To help market the invention, Zybach recruited and sold 49% interest in the patent rights to businessman A.E. Trowbridge. The two then relocated to Columbus, Nebraska, which had the potential of a better market, and continued developing and spreading the word about the new central-pivot. Still, the two found did not find success initially, which is when they were introduced to local businessman Robert B. Daugherty in 1954. Daugherty had “spent his life savings – $5,000 – to start a small business on a farm west of Valley, [Nebraska]” called Valley Manufacturing (Mader 2010). Zybach and Trowbridge eventually agreed to sell the rights to the patent to Daugherty, and in return the two received a 5% royalty for every center-pivot irrigation system produced until the 1969 when the patent expired. For many years Valley Manufacturing worked to make improvements to the system, and by the late 1960s the company had turned “it into ‘the most significant mechanical innovation in agriculture since the replacement of draft animals by the tractor’” (Ganzel 2006). From here the industry took off with the number of systems in use growing exponentially across the United States (Figure II). In just a few years extensive proliferation of the central-pivot irrigation system took over the rural landscape across a majority of the United States and in nine states it became the primary form of irrigation (McKnight 1979, 119).

Geography limited the impact of central pivot irrigation in Nebraska, however. “Much of Nebraska is unsuitable for traditional gravity irrigation methods either because the land is too hilly or the soil too sandy. The center-pivot has allowed development of these lands for irrigation in many parts of the state” (Aiken 1979, 618). The system could be adapted not just to the sand dunes of western Nebraska, but almost anywhere in the world where the land was previously only capable of supporting livestock grazing (McKnight 1979, 74)]. Therefore this new technology revolutionized agriculture by opening up new terrains for farmers to cultivate while also making both labor and water use more efficient (Figure 3).

Today there are still many center-pivot irrigation systems in use or some variation of Zybach’s invention. In fact, as of 2008 “More than a quarter-million center-pivot irrigation systems now water fields around the world” (Alfred). In addition, the company that Daugherty began all the way back in 1946 is still in business today. In fact the company, now named Valley Industries, has a location in Omaha that still claims to be the worldwide leader in precision irrigation and the center-pivot.

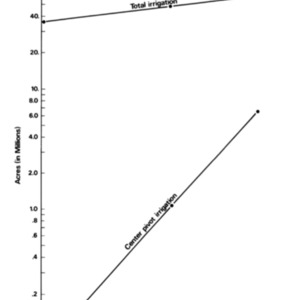

The center pivot irrigation system transformed agriculture in the American Midwest. Since the first irrigation system was put into use the momentum of innovation has only increased. During the 44-year period of 1921 and 1965, enough wells were drilled in Nebraska in order to irrigate 2,914,000 acres of cropland with most of this being driven by necessity due to droughts. (Figure IV) In just the 10-year period between 1965 and 1975 an additional 2,136,000 were added to those already irrigated. The marked increase shows the importance of the technology. The center pivot irrigation system accounts for 60-70% of this increase (Drought Put Spurs to Irrigators 1975). This explosion was not without reason. Frank Zybach himself described the system as superior to all previous irrigation systems because “...more effective and adequate watering can be accomplished by sprinkling the water onto the land (Zybach 1960, 6).”

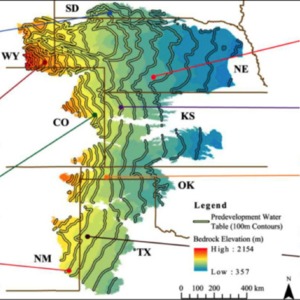

Center pivot irrigation systems are having severe negative impacts on the environment as well. The global impacts of aquifer depletion are represented by the drawdown of the High Plains aquifer. The Ogallala Aquifer is one of the largest water aquifers in the world. It spans portions of eight states and runs from South Dakota to Texas. The Ogallala Aquifer is under 225,000 square miles of land mass in the Great Plains region (Glantz 1989). As such, it has been the perfect candidate to be drilled and overexploited by irrigation. If you refer to Figure 2 you can see the prominence of center pivot irrigation systems over top of the Ogallala Aquifer. From 2011 to 2013, the Ogallala Aquifer dropped 36 million acre-feet (Salter 2016). Use of this aquifer is especially frightening because of the regions massive reliance on it, and the aquifers extremely slow recharge rate. Numerous droughts in the High Plains Region slowly increased farmers’ reliance on irrigation. Water taken out though, does not go back in at the same rate; almost all precipitation over the Ogallala Aquifer evaporates off or is consumed by plants, which makes the aquifer’s recharge rate slight-negligible (Kennamer 1959, 211). If the water level continues to drop at its current rate, eventually the Ogallala and other aquifers will run dry and there will be a major crop shortage around the world (Figure V). This problem is only expounded as the planet continues to warm because of climate change and plants in turn need more and more water from the ground as it evaporates in higher rates.

Today, it is one of the driving forces of agricultural expansion and, as a result, an important component of the Anthropocene discourse. This invention increased food production across the planet and allowed for plants that need large quantities of water to be grown on dry lands. An extreme example of this is a research program that was able to grow rice in a drier region of Missouri. Although this technique was not without problems because the traditional flooding of rice fields for weed control was replaced by heavy nitrogen fertilization and herbicide application (CAFNR Missouri 2008). Another reason center pivot irrigation is so effective and popular is because it works on most soil types and soil gradients. Gravity-driven forms of irrigation cannot operate on slopes so the center pivot irrigation system is more effective for these uses (Gray 2014).

If the anthropocene is defined as a proposed new geological epoch characterized by human exploitation and domination of our natural environment, then irrigation is one of the biggest pieces of evidence supporting this argument. Center pivot irrigation systems have massive effects on the environment in multiple ways. The systems pull millions of gallons of groundwater from the water table, which drains aquifers in dry years. If irrigators install too many systems in one area they may pollute the water table, especially in sandy regions where water is easily able to carry pesticides and fertilizers back into the deep earth. These concerns are not new/ Even as far back as 1979, concerns were being raised about the sustainability of an irrigation system relying this heavily on ground water use. One concerned citizen stated that, “I have been warned that no civilization based upon agriculture can survive” (Schmit 1979).

On a global scale, one-sixth of cropland that is irrigated and one-third of the total food is grown using this mined water (Stockle 2002, 1). 60% of irrigation in the United States pulls water directly from underground aquifers and nearly 90% of total freshwater use in the world is used in irrigation (Scanlon 2012). The environmental impacts are hard to ignore. In 2011 and 2012 the aquifer under Kansas dropped an average of 4.25 feet across the state. In the previous 15 years, the water table had only fallen 8.5 feet. (Wines 2013). This is not a surprise though when you look at the proportion of total irrigation that relies on groundwater as its source of water. Part of the reason such a large proportion of the irrigation in the United States comes from underground sources, is not just because the rate of irrigation is increasing, but additionally because groundwater irrigation methods such as central pivot irrigation are actually replacing surface water irrigation methods that would have less of an effect on the environment but are more costly (Figure 3). This is not a problem that will be going be away anytime soon. As the world’s population continues to grow at an exponential rate, more wells for center pivot irrigation systems will be drilled to produce more food with less farmland. The irrigation systems will also have to be run for longer and more times as global warming increases the average temperature and extreme drought weather events increase in rate of occurrence.[1] The Neolithic Revolution, which involved the transition from a hunter and gatherer lifestyle to one of settlement and agriculture, and other innovations in tools, harvesting techniques, and fertilizers, such as the 19th century guano trade, have also been termed agricultural revolutions throughout history.

Creator

Ethan Sperfslage

Source

Aiken, J. David and Supalla, Raymond J., "Ground Water Mining and Western Water Rights Law: the Nebraska Experience" (1979). Faculty Publications: Agricultural Economics. Accessed October 10, 2018. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1025&context=ageconfacpub

Alfred, Randy. "July 22, 1952: Genuine Crop-Circle Maker Patented." Wired. July 22, 2008.Accessed October 10, 2018. https://www.wired.com/2008/07/dayintch-0722/.

Aucoin, James. “The Irrigation Revolution and Its Environmental Consequences.” Environment:Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, vol. 21, no. 8, 1979, pp. 17–38.

"Drought Put Spurs to Irrigators." Omaha World-Herald, September 10, 1975.

"First Pivots Installed." Living History Farm. 2006. Accessed December 15, 2018. https://livinghistoryfarm.org/farminginthe50s/water_06.html.

Ganzel, Bill. "Center Pivots Take Over." Center Pivot Irrigation Systems Take Over During the 1950s. 2006. Accessed October 10, 2018. https://livinghistoryfarm.org/farminginthe50s/water_03.html.

Glantz, Michael. "The Ogallala Aquifer Depletion." Meteor. 1989. Accessed October 10, 2018. http://www.meteor.iastate.edu/gccourse/issues/society/ogallala/ogallala.html

Gray, Ellen. "Texas Crop Circles from Space." Global Climate Change: Vital Signs of the Planet. September 16, 2014. Accessed October 10, 2018. https://climate.nasa.gov/news/729/texas-crop-circles-from-space/.

"Growing Rice Where It Has Never Been Grown before." College of Agriculture, Food, and Natural Resources. July 3, 2008. Accessed October 10, 2018.

Hallberg, G.R., 1976, Irrigation in Iowa: Part II: An overview of the needs, the costs, the problems: Iowa Geol. Surv., Tech. Info. Ser. , No. 5, 55 p. Accessed October 10, 2018.

Kennamer, Lorrin. “Irrigation Patterns in Texas.” The Southwestern Social Science Quarterly,vol. 40, no. 3, 1959, pp. 203–212. JSTOR. Accessed October 10, 2018.

Mader, Shelli, and Kan Hays. "Center Pivot Irrigation Revolutionizes Agriculture." The Fence Post. May 25, 2010. Accessed October 10, 2018. https://www.thefencepost.com/news/center-pivot-irrigation-revolutionizes-agriculture/.

McKnight, Tom L. “California' s Reluctant Acceptance of Center Pivot Irrigation.” Yearbook of the Association of Pacific Coast Geographers, vol. 41, 1979, pp. 119–138.

McKnight, Tom L. “Great Circles on the Great Plains: The Changing Geometry of American Agriculture (Große Kreise Auf Den Great Plains: Die Sich Wandelnde Geometrie Der Amerikanischen Land-Wirtschaft).” Erdkunde, vol. 33, no. 1, 1979, pp. 70–79.

Paskach, Robert. Man Walking in Field next to a Crop Irrigation Pivot. 1979-1983. Robert Paskach Collection, Durham Museum, Omaha.

Salter, John L. "Center Pivot Irrigation and The Ogallala Aquifer." Mathematics for Sustainability: Spring 2016. February 20, 2016. Accessed October 10, 2018.https://sites.psu.edu/math033spring16/2016/02/19/center-pivot-irrigation-and-the- ogallala-aquifer/.

Scanlon, B. R., et al. “Groundwater Depletion and Sustainability of Irrigation in the US High Plains and Central Valley.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 109, no. 24, 2012, pp. 9320–9325., doi:10.1073/pnas.1200311109. Accessed October 10, 2018

Schmit, Loran. "NRD Control Is Local Over Water Resources." Omaha World-Herald, October 3, 1979.

Steward, David R., and Andrew J. Allen. "Peak Groundwater Depletion in the High Plains Aquifer, Projections from 1930 to 2110." Agricultural Water Management 170 (June 24, 2016): 36-48. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2015.10.003.https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378377415301220#fig0010

Stockle, Claudio O. “Environmental Impact of Irrigation: A Review.” Pennsylvania State University.

Wines, Michael. "Wells Dry, Fertile Plains Turn to Dust." NY Times. May 19, 2013. Accessed October 10, 2018. Zybach, Frank L. Self-Propelled Sprinkling Irrigating Apparatus. 21June 1960. Accessed October 10, 2018.https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/7f/e0/94/c81f64deeb0671/US2941727.pdfRights

Collection

Citation

Embed

Copy the code below into your web page