Bison

Title

Bison

Subject

This is Scout, a symbol of the fall and rise of the American Bison. Before westward expansion in the 1800s, between 30-60 million bison roamed the Great Plains. They played an important role in the ecosystems. For example, bison ‘wallowed’ or rolled in the dirt to get rid of insects and to cool off. At the same time, this behavior created depressions that encouraged new plant growth. Bison are central to Native American cultures on the Great Plains. They used bison for food, shelter, clothing, and ceremonies. When European settlers moved west, bison became commodities and hunts grew in size. By 1889, less than 2,000 bison remained. But, recent conservation efforts are increasing their numbers. Nebraska is the second highest producer of bison in the U.S. Although bison will never return to the prominence they once held in the Midwest, their recovery story, which Nebraska is a part of, inspires hope for their future.

Description

Visitors of the Durham Museum begin their journey through history with Scout. Scout is a North American Bison who has been a part of the Durham collection since 2006 (Figure 1). Scout’s story is complicated. On the one hand, he represents bisons' past dominance of the prairies and their erased ecological system. Scout reminds us of the slaughter and near extinction of his species brought about by humans. On the other hand, Scout represents the Bison bison’s slow, but persistent recovery. Both stories are part of the Anthropocene narrative. Human activity, specifically Euroamerican settlement, were the main destructive force behind bisons' near extinction. Slaughtered in the millions for their hides, horns, and meat during the nineteenth century, the rapaciousness of western expansion was certainly culpable for their decline. However, people have also played a major role in bisons' recovery, an often untold but necessary narrative that inspires hope for the future of bison. The bison is an important artifact in Omaha’s environmental history because they were once the dominant keystone species of the grasslands, but now have been reduced to peripheral importance. It links Omaha’s environmental history to the global history of the Anthropocene by epitomizing human power over nature.

Bison once dominated the Great Plains. According to Colonel Richard I. Dodge, the commander of Fort Dodge, KS in 1851, there were "60 million bison in primitive North America” (D. Lott, 2003). Twenty years after the Civil War, bison population was below two thousand. The dramatic decline of the keystone species had cascading influences across the Plains ecosystems. For example, bison urine, wallowing, and carcasses all uniquely contributed to the ecological health of the Great Plains. According to Flannery, a professor at the University of Adelaide in Australia and the director of the South Australian Museum, "the key to the bison's role in the prairie ecosystem lay in the fact that the great grasslands were piss-driven" (T. Flannery, 2001). Bison urine is essentially "a bath of nitrogen dissolved in water," which means that the urine leaves behind a high concentration of ammonium and nitrate in the soils (D. Lott, 2003). Wallowing, or rolling on the ground, relieved bison of insects and heat. More importantly, this created “compacted bowls of soil that hold rainwater, creating a microenvironment in which seeds can sprout” (D. Lott, 2003). Essentially, bison urine and wallowing laid groundwork for healthy plant growth and diversity. Last, bison carcasses played a key role in the ecology of the Great Plains. Not only are carcasses a food source for other animals, but they release fluids that eventually create “zones of high fertility" (A. Knapp, et. al. 1999). These characteristics exemplify the codependence between the bison and the prairie.

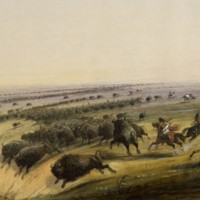

The Native Americans were the first humans to interact with the bison. Soon, the tribes of the Great Plains became dependent on bison for hunting. Initially, Native Americans tactics involved disguises that allowed them to hunt with greater accuracy (V. Geist, 1996). However, the introduction of the horse in the 1600s made game driving the gold standard (V. Geist, 1996). Although bison hunting has been part of North American history for centuries, its height was during Euroamerican westward expansion in the 1800s. This expansion propelled the destruction of bison in numerous ways. First, natural catastrophes and Pre-Euroamerican activity impacted bison populations. From drowning when fording a river to the harsh winter weather of the plains, bison faced life-threatening situations constantly. As McHugh, a biologist and zoologist with a background in wildlife management, states, “the ravages of nature were taking a recurrent, at times disastrous, toll of the herds” (T. McHugh, 2004). For example, in 1867 “a herd of four thousand bison attempting to ford the Platte River in Nebraska walked into channels of loose quicksand" (T. McHugh, 2004). As the lead bison were slipping into the sand the remaining herd kept moving, causing the death of two thousand bison. Devastation surged with the increased influence of humans on the herds. For example, “[Paleoindians] would drive a bison herd into a gully, a canyon, or some other natural trap having inescapable sides” (H. P. Danz, 1997). This game driving (Figure 2), allowed hunters to easily kill large amounts of bison. Particularly, when bison were driven off cliffs and maimed, hunters could finish them off without using ammunition.

Lewis and Clark, two famous westward explorers of the 1800s, described this phenomenon in their journals when they observed a young Indian man deceiving bison herds by disguising himself:

the skin of the head with the ears and horns fastened on his own head in such a way as to deceive the buffalo … the disguised Indian leads them on at full speed towards the river, when suddenly securing himself in some crevice of the cliff (H. P. Danz, 1997).

This manipulation of animals and nature demonstrates the impacts humans had on bison populations during the period. Although Pre-Euroamerican impacts and nature decreased bison populations, it was the industrial revolution that put them in grave danger.

The industrial revolution was an important precondition for the decline of bison herds. The introduction of the railroad through the Midwest provided quick and easy transport of people and material. This made the plains more accessible for Euroamericans, and with the romanticizing of bison hunting by many Europeans, much more popular. This idealistic view of wild animals paired with increased access and easy transportation propelled the destruction forward.

With the introduction of railways and westward expansion, bison habitat shrank dramatically. With the landscape disappearing, bison herd bunched. This "resulted in harmful competition" especially during times of drought, food shortages, and heavy snow (H. P. Danz, 1997). Furthermore, crowded herds furnished an "easy route for the spread of parasites and disease" such as anthrax and tuberculosis (H. P. Danz, 1997). Prevalent disease paired with other human influences created excellent conditions for hunting, but, by the end of the nineteenth century, led to the near extinction of the North American bison.

Slaughtering bison was as much a political act as it was economic and environmental. Euroamerican conflicts with Native Americans prompted the American government to actively hunt and kill bison. Great Plain tribes such as the Sioux, Blackfoot, Arapaho, Cheyenne, Arikara, Pawnee, Wichita, Kiowa, and Comanche depended on the bison for their very existence. The bison served many purposes for them. Although primarily used for food, bison also provided hide for housing, clothing, and bedding; bones, organs, and feces were used as fuel and markers (H. P. Danz, 1997). Native Americans placed religious importance and mystical symbolism on bison, especially white bison. Occasionally, an albino or light cream-colored bison would materialize in a herd “an event that nearly always resulted in the eventual killing, or sacrifice, of the animal, followed by ritualistic and religious ceremonies” (H. P. Danz, 1997).

Knowing that these tribes revered and depended on bison, the American government targeted bison as a way to undermine Native American culture and reduce their populations. In 1873, for instance, President Grant's Secretary of the Interior, Columbus Delano wrote, "'I would not seriously regret the total disappearance of the buffalo from our western prairies, in its effect upon the Indians' … the destruction of the herds would have a beneficial effect in reducing Indian resistance"(S. M. Taylor, 2011). Although no official statement from the Army states they intentionally targeted bison, it was clear through their eagerness to break Indian resistance. Railroads, from a tactical perspective, also played a large role in their late nineteenth century decline. When it was discovered that the Union Pacific and Kansas Pacific railroads interfered with bison territory, military commanders increased their pressure on bison herds. This strategy cleared the path for railroads and undermined Native American societies in the area. In the words of Army General Philip Sheridan, "I think it would be wise to invite all the sportsmen of England and America this fall for a Grand Buffalo hunt" (D. D. Smits, 1994). Military commanders also deliberately permitted their troops to kill bison in order to decimate the Native American frontier. After all, the bison and the Plains tribes were inseparable and the bison were an easier target. The destruction of the bison was a political and economic act that fundamentally reshaped the human ecology of the Great Plains.

Even though human involvement and natural catastrophes devastated bison herds throughout the United States, the force driving the slaughter of bison was capitalism. Because the supply of bison was so plentiful and the railroads made shipping quicker, companies, such as the American Fur Company, could "sell the [bison fur] robes at a moderate price and still reap profit" (Isenberg, 2000). This, however, put "heavy pressure on the herds" themselves (Isenberg, 2000). Ultimately, profits depended less on the price of the robes than "on the sheer volume shipped east" (Isenberg, 2000). According to environmental historian Andrew Isenberg, the Native Americans participated in the bison robe trade. Native Americans also participated in the beaver fur trade that spanned between the late 1600s to the early 1800s. Similar to the bison trade, the Euroamericans prized beaver fur and Native American tribes hunted beaver for food. However, other game, such as muskrat, mink, otter, and lynx were available in the case of beaver shortages (A. J. Ray, 2017). The difference between the bison fur trade and the beaver fur trade was that the nomadic lifestyle of the bison was mirrored by the Native Americans on the Great Plains. Thus, even though Native American tribes participated in the beaver trade, the tribes on the Great Plains experienced greater difficulties when they transformed their main source of livelihood, the bison, into capital. From the Euroamerican perspective, Native American involvement benefited the American Fur Company so much that by 1835, “an average of over 130,000” bison robes were shipped per year (Isenberg, 2000). This, in conjunction with the fixed low robe prices, made profits dependent on the volume of bison robes rather than on their prices. These industrial pressures caused the western plains to become “a remote extension of the global industrial economy and an object of its demand for natural resources" (Isenberg, 2000). This exploitation nearly brought the North American bison to extinction, all the while fueling the United States’ global economy.

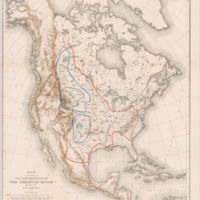

The story of the downfall of the bison is a sad one. By 1889, there were only “1,089 bison left in North America” (H. R. Harris, 1920). The diagram pictured above (Figure 3) shows the decline of bison herds after Euroamerican expansion in1889. However, a more recent history, of which Scout is a part of, is hopeful. Today, “approximately 500,000 bison live across North America” (Defenders.org, “Basic Facts About Bison"). Populations persisted in Canada and, surprisingly, on Catalina Island. 23 bison were brought to this foreign island to film a movie, but ended up staying when 22 new bison were imported to Catalina Island between 1969 and 1971 to mix with the island herd and maintain population health (R. A. Sweitzer, et. al. 2005). Again, bison were saved from near extinction “in the late 1800s by 5 private herds established by ranchers and by a sixth herd at the New York Zoological Park”, meaning that the present-day plains bison population is “descended from less than 100 founders” (P. W. Hedrick, 2009). Because the number of bison remaining on the continent was so limited, conservation promoted hybridization between bison and cattle. Breeding bison with cattle resulted in a changed population, however. A scientific study demonstrated that in both a nutritionally poor environment (Santa Catalina Island, California) and a nutritionally rich environment (Montana), bison with cattle mtDNA had lower body weights and were shorter than their counterparts with bison mtDNA (J. N. Derr, et. al. 2012). Although this decreases the bison's overall fitness due to the smaller stature, it keeps alive some degree of bison. Some critics complain that this does not stay true to conserving organic bison, but this is a critical step in the right direction for the conservation of bison in modern times.

These early successes prompted a wave of recent efforts to sustainably increase bison populations and reintroduce them to the American Midwest. In the late 1900s, organizations such as the National Bison Association and the Canadian Bison Association worked with individuals to promote raising bison in every state and nearly every province, especially those with plains (D. E. Popper and F. J. Popper, 2006). Wealthy entrepreneurs and conservations have even gone so far as to promote the recovery of large regions of the plains as a bison ecosystem, a movement known as Buffalo Commons. This movement has “coincided with numbers of important shifts: from a paradigm of mastery of nature to one of cooperation based on ecology… As one result… prairie dogs were saved from extermination in Lubbock, Texas, because of their identified role in the ecosystem” (D. E. Popper and F. J. Popper, 2006). These efforts are part of a global movement to “rewild” anthropogenic landscapes, breed endangered or even extinct animals.

Today, bison have reemerged as an economically significant source of food. A Nebraskan farmer, Dave Hutchinson, was recognized in September 2017 in the Omaha World Herald for promoting organic bison, "raised and finished on grass" (S. B. Hansen, 2017). His land “has been certified organic since 1980 and his animals since 1990” (S. B. Hansen, 2017). This is particularly notable for Nebraska because according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture's 2012 Census of Agriculture, there's "about 23,000 bison in Nebraska and 88 operations raising the animals, making Nebraska the second highest producer, behind South Dakota" (S. B. Hansen, 2017). Certainly, the attitude towards bison is shifting towards an approach that encourages natural bison growth, in Nebraska, nationally, and internationally. Hutchinson’s farm attracts local, domestic, and foreign visitors that are intrigued by his dedication to organic farming and conservation. Hutchinson demonstrates how humans can positively employ their power to help conserve nature.

Nebraskans continue to be a leading force in bison conservation. Across the U.S., the bison is now considered the national mammal (World-Herald Editorial, 2016). Nebraskans recognize the bison’s impact on Great Plains ecology and Native American culture. U.S. Representative Jeff Fortenberry of Nebraska, a sponsor of the National Bison Legacy Act, says, “bison have a storied history in Nebraska and are an important part of our nation’s frontier heritage… By naming bison as our national mammal, we are supporting the ongoing preservation of this majestic species and their essential tie to the American experience” (World-Herald Editorial, 2016). This admiration for the North American bison inspires a spirit of activism towards the bison that once roamed the Great Plains.

Bison will never reassume the prominence they once held in Midwest ecologies and human societies. From that perspective, a twenty first century bison like Scout serves as a culturally resonant reminder of past mistakes. The massive decline in the bison population demonstrates our selfish, greedy nature that drives us to push nature and its creatures to its limits. However, the bison recovery represents a different perspective on the Anthropocene. It shows that with conscious effort, humans also have the capability to create new relationships with nature.

Bison once dominated the Great Plains. According to Colonel Richard I. Dodge, the commander of Fort Dodge, KS in 1851, there were "60 million bison in primitive North America” (D. Lott, 2003). Twenty years after the Civil War, bison population was below two thousand. The dramatic decline of the keystone species had cascading influences across the Plains ecosystems. For example, bison urine, wallowing, and carcasses all uniquely contributed to the ecological health of the Great Plains. According to Flannery, a professor at the University of Adelaide in Australia and the director of the South Australian Museum, "the key to the bison's role in the prairie ecosystem lay in the fact that the great grasslands were piss-driven" (T. Flannery, 2001). Bison urine is essentially "a bath of nitrogen dissolved in water," which means that the urine leaves behind a high concentration of ammonium and nitrate in the soils (D. Lott, 2003). Wallowing, or rolling on the ground, relieved bison of insects and heat. More importantly, this created “compacted bowls of soil that hold rainwater, creating a microenvironment in which seeds can sprout” (D. Lott, 2003). Essentially, bison urine and wallowing laid groundwork for healthy plant growth and diversity. Last, bison carcasses played a key role in the ecology of the Great Plains. Not only are carcasses a food source for other animals, but they release fluids that eventually create “zones of high fertility" (A. Knapp, et. al. 1999). These characteristics exemplify the codependence between the bison and the prairie.

The Native Americans were the first humans to interact with the bison. Soon, the tribes of the Great Plains became dependent on bison for hunting. Initially, Native Americans tactics involved disguises that allowed them to hunt with greater accuracy (V. Geist, 1996). However, the introduction of the horse in the 1600s made game driving the gold standard (V. Geist, 1996). Although bison hunting has been part of North American history for centuries, its height was during Euroamerican westward expansion in the 1800s. This expansion propelled the destruction of bison in numerous ways. First, natural catastrophes and Pre-Euroamerican activity impacted bison populations. From drowning when fording a river to the harsh winter weather of the plains, bison faced life-threatening situations constantly. As McHugh, a biologist and zoologist with a background in wildlife management, states, “the ravages of nature were taking a recurrent, at times disastrous, toll of the herds” (T. McHugh, 2004). For example, in 1867 “a herd of four thousand bison attempting to ford the Platte River in Nebraska walked into channels of loose quicksand" (T. McHugh, 2004). As the lead bison were slipping into the sand the remaining herd kept moving, causing the death of two thousand bison. Devastation surged with the increased influence of humans on the herds. For example, “[Paleoindians] would drive a bison herd into a gully, a canyon, or some other natural trap having inescapable sides” (H. P. Danz, 1997). This game driving (Figure 2), allowed hunters to easily kill large amounts of bison. Particularly, when bison were driven off cliffs and maimed, hunters could finish them off without using ammunition.

Lewis and Clark, two famous westward explorers of the 1800s, described this phenomenon in their journals when they observed a young Indian man deceiving bison herds by disguising himself:

the skin of the head with the ears and horns fastened on his own head in such a way as to deceive the buffalo … the disguised Indian leads them on at full speed towards the river, when suddenly securing himself in some crevice of the cliff (H. P. Danz, 1997).

This manipulation of animals and nature demonstrates the impacts humans had on bison populations during the period. Although Pre-Euroamerican impacts and nature decreased bison populations, it was the industrial revolution that put them in grave danger.

The industrial revolution was an important precondition for the decline of bison herds. The introduction of the railroad through the Midwest provided quick and easy transport of people and material. This made the plains more accessible for Euroamericans, and with the romanticizing of bison hunting by many Europeans, much more popular. This idealistic view of wild animals paired with increased access and easy transportation propelled the destruction forward.

With the introduction of railways and westward expansion, bison habitat shrank dramatically. With the landscape disappearing, bison herd bunched. This "resulted in harmful competition" especially during times of drought, food shortages, and heavy snow (H. P. Danz, 1997). Furthermore, crowded herds furnished an "easy route for the spread of parasites and disease" such as anthrax and tuberculosis (H. P. Danz, 1997). Prevalent disease paired with other human influences created excellent conditions for hunting, but, by the end of the nineteenth century, led to the near extinction of the North American bison.

Slaughtering bison was as much a political act as it was economic and environmental. Euroamerican conflicts with Native Americans prompted the American government to actively hunt and kill bison. Great Plain tribes such as the Sioux, Blackfoot, Arapaho, Cheyenne, Arikara, Pawnee, Wichita, Kiowa, and Comanche depended on the bison for their very existence. The bison served many purposes for them. Although primarily used for food, bison also provided hide for housing, clothing, and bedding; bones, organs, and feces were used as fuel and markers (H. P. Danz, 1997). Native Americans placed religious importance and mystical symbolism on bison, especially white bison. Occasionally, an albino or light cream-colored bison would materialize in a herd “an event that nearly always resulted in the eventual killing, or sacrifice, of the animal, followed by ritualistic and religious ceremonies” (H. P. Danz, 1997).

Knowing that these tribes revered and depended on bison, the American government targeted bison as a way to undermine Native American culture and reduce their populations. In 1873, for instance, President Grant's Secretary of the Interior, Columbus Delano wrote, "'I would not seriously regret the total disappearance of the buffalo from our western prairies, in its effect upon the Indians' … the destruction of the herds would have a beneficial effect in reducing Indian resistance"(S. M. Taylor, 2011). Although no official statement from the Army states they intentionally targeted bison, it was clear through their eagerness to break Indian resistance. Railroads, from a tactical perspective, also played a large role in their late nineteenth century decline. When it was discovered that the Union Pacific and Kansas Pacific railroads interfered with bison territory, military commanders increased their pressure on bison herds. This strategy cleared the path for railroads and undermined Native American societies in the area. In the words of Army General Philip Sheridan, "I think it would be wise to invite all the sportsmen of England and America this fall for a Grand Buffalo hunt" (D. D. Smits, 1994). Military commanders also deliberately permitted their troops to kill bison in order to decimate the Native American frontier. After all, the bison and the Plains tribes were inseparable and the bison were an easier target. The destruction of the bison was a political and economic act that fundamentally reshaped the human ecology of the Great Plains.

Even though human involvement and natural catastrophes devastated bison herds throughout the United States, the force driving the slaughter of bison was capitalism. Because the supply of bison was so plentiful and the railroads made shipping quicker, companies, such as the American Fur Company, could "sell the [bison fur] robes at a moderate price and still reap profit" (Isenberg, 2000). This, however, put "heavy pressure on the herds" themselves (Isenberg, 2000). Ultimately, profits depended less on the price of the robes than "on the sheer volume shipped east" (Isenberg, 2000). According to environmental historian Andrew Isenberg, the Native Americans participated in the bison robe trade. Native Americans also participated in the beaver fur trade that spanned between the late 1600s to the early 1800s. Similar to the bison trade, the Euroamericans prized beaver fur and Native American tribes hunted beaver for food. However, other game, such as muskrat, mink, otter, and lynx were available in the case of beaver shortages (A. J. Ray, 2017). The difference between the bison fur trade and the beaver fur trade was that the nomadic lifestyle of the bison was mirrored by the Native Americans on the Great Plains. Thus, even though Native American tribes participated in the beaver trade, the tribes on the Great Plains experienced greater difficulties when they transformed their main source of livelihood, the bison, into capital. From the Euroamerican perspective, Native American involvement benefited the American Fur Company so much that by 1835, “an average of over 130,000” bison robes were shipped per year (Isenberg, 2000). This, in conjunction with the fixed low robe prices, made profits dependent on the volume of bison robes rather than on their prices. These industrial pressures caused the western plains to become “a remote extension of the global industrial economy and an object of its demand for natural resources" (Isenberg, 2000). This exploitation nearly brought the North American bison to extinction, all the while fueling the United States’ global economy.

The story of the downfall of the bison is a sad one. By 1889, there were only “1,089 bison left in North America” (H. R. Harris, 1920). The diagram pictured above (Figure 3) shows the decline of bison herds after Euroamerican expansion in1889. However, a more recent history, of which Scout is a part of, is hopeful. Today, “approximately 500,000 bison live across North America” (Defenders.org, “Basic Facts About Bison"). Populations persisted in Canada and, surprisingly, on Catalina Island. 23 bison were brought to this foreign island to film a movie, but ended up staying when 22 new bison were imported to Catalina Island between 1969 and 1971 to mix with the island herd and maintain population health (R. A. Sweitzer, et. al. 2005). Again, bison were saved from near extinction “in the late 1800s by 5 private herds established by ranchers and by a sixth herd at the New York Zoological Park”, meaning that the present-day plains bison population is “descended from less than 100 founders” (P. W. Hedrick, 2009). Because the number of bison remaining on the continent was so limited, conservation promoted hybridization between bison and cattle. Breeding bison with cattle resulted in a changed population, however. A scientific study demonstrated that in both a nutritionally poor environment (Santa Catalina Island, California) and a nutritionally rich environment (Montana), bison with cattle mtDNA had lower body weights and were shorter than their counterparts with bison mtDNA (J. N. Derr, et. al. 2012). Although this decreases the bison's overall fitness due to the smaller stature, it keeps alive some degree of bison. Some critics complain that this does not stay true to conserving organic bison, but this is a critical step in the right direction for the conservation of bison in modern times.

These early successes prompted a wave of recent efforts to sustainably increase bison populations and reintroduce them to the American Midwest. In the late 1900s, organizations such as the National Bison Association and the Canadian Bison Association worked with individuals to promote raising bison in every state and nearly every province, especially those with plains (D. E. Popper and F. J. Popper, 2006). Wealthy entrepreneurs and conservations have even gone so far as to promote the recovery of large regions of the plains as a bison ecosystem, a movement known as Buffalo Commons. This movement has “coincided with numbers of important shifts: from a paradigm of mastery of nature to one of cooperation based on ecology… As one result… prairie dogs were saved from extermination in Lubbock, Texas, because of their identified role in the ecosystem” (D. E. Popper and F. J. Popper, 2006). These efforts are part of a global movement to “rewild” anthropogenic landscapes, breed endangered or even extinct animals.

Today, bison have reemerged as an economically significant source of food. A Nebraskan farmer, Dave Hutchinson, was recognized in September 2017 in the Omaha World Herald for promoting organic bison, "raised and finished on grass" (S. B. Hansen, 2017). His land “has been certified organic since 1980 and his animals since 1990” (S. B. Hansen, 2017). This is particularly notable for Nebraska because according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture's 2012 Census of Agriculture, there's "about 23,000 bison in Nebraska and 88 operations raising the animals, making Nebraska the second highest producer, behind South Dakota" (S. B. Hansen, 2017). Certainly, the attitude towards bison is shifting towards an approach that encourages natural bison growth, in Nebraska, nationally, and internationally. Hutchinson’s farm attracts local, domestic, and foreign visitors that are intrigued by his dedication to organic farming and conservation. Hutchinson demonstrates how humans can positively employ their power to help conserve nature.

Nebraskans continue to be a leading force in bison conservation. Across the U.S., the bison is now considered the national mammal (World-Herald Editorial, 2016). Nebraskans recognize the bison’s impact on Great Plains ecology and Native American culture. U.S. Representative Jeff Fortenberry of Nebraska, a sponsor of the National Bison Legacy Act, says, “bison have a storied history in Nebraska and are an important part of our nation’s frontier heritage… By naming bison as our national mammal, we are supporting the ongoing preservation of this majestic species and their essential tie to the American experience” (World-Herald Editorial, 2016). This admiration for the North American bison inspires a spirit of activism towards the bison that once roamed the Great Plains.

Bison will never reassume the prominence they once held in Midwest ecologies and human societies. From that perspective, a twenty first century bison like Scout serves as a culturally resonant reminder of past mistakes. The massive decline in the bison population demonstrates our selfish, greedy nature that drives us to push nature and its creatures to its limits. However, the bison recovery represents a different perspective on the Anthropocene. It shows that with conscious effort, humans also have the capability to create new relationships with nature.

Creator

Chelsey Dizon

Kevin Vincent

Kevin Vincent

Source

“Basic Facts About Bison.” Defender.org. https://defenders.org/bison/basic-facts (26 November 2017).

Danz, Harold P. Of Bison and Man: From the Annals of a Bison Yesterday to a Refreshing Outcome from Human Involvement with America's Most Valiant of Beasts. Niwot: University Press of Colorado, 1997.

Derr, James N., Philip W. Hedrick, Natalie D. Halbert, Louis Plough, Lauren K. Dobson, Julie King, Calvin Duncan, David L. Hunter, Noah D. Cohen, and Dennis Hedgecock. "Phenotypic Effects of Cattle Mitochondrial DNA in American Bison." Conservation Biology 26, no. 6 (2012): 1130-136. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2012.01905.x.

Flannery, Tim F. The Eternal Frontier: An Ecological History of North America and Its Peoples. London: Penguin, 2001.

Geist, Valerius. Buffalo nation: history and legend of the North American bison. Stillwater, MN: Voyageur Press, 1996.

Hansen, Sarah Baker. "Nebraska Man Raises Organic Bison." Omaha World-Herald, September 17, 2017. Accessed November 7, 2017. https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/nebraska/articles/2017-09-17/nebraska-man-raises-organic-bison.

Harris, H. R. ""John Full of Pep," Only Surviving Paleface to Hunt Buffaloes with Pawnees, Recalls Days when Hoof Beats Resembled Thunder on Plains." The Omaha Sunday Bee, August 29, 1920. Accessed December 10, 2017.

Hedrick, Philip W. “Conservation Genetics and North American Bison.” Journal of Heredity 100, no. 4 (July 2009): 411-420. doi:10.1093/jhered/esp024

Isenberg. The Destruction of the Bison: An Environmental History, 1750-1920 (Studies in Environment and History). Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Knapp, A., J. Blair, J. Briggs, S. Collins, D. Hartnett, L. Johnson, and E. Towne. "The Keystone Role of Bison in North American Tallgrass Prairie: Bison Increase Habitat Heterogeneity and Alter a Broad Array of Plant, Community, and Ecosystem Processes."BioScience, 1999. doi:10.1525/bisi.1999.49.1.39.

Lott, Dale F. American Bison: a Natural History. University of California Press, 2003.

McHugh, Tom. The Time of the Buffalo. New Jersey: Castle Books, 2004.

Popper, Deborah E., and Frank J. Popper. "The onset of the Buffalo Commons." Journal of the West 45, no. 2 (2006): 29.

Ray, Arthur J. Indians in the Fur Trade: their roles as trappers, hunters, and middlemen in the lands southwest of hudson bay, 1660-1870. Toronto: Univ of Toronto Press, 2017.

Smits, David D. "The Frontier Army and the Destruction of the Buffalo: 1865-1883." The Western Historical Quarterly 25, no. 3 (1994): 312. doi:10.2307/971110.

Sweitzer, RICK A., Juanita M. Constible, Dirk H. Van Vuren, PETER T. Schuyler, and FRANK R. Starkey. "History, habitat use and management of bison on Catalina Island, California." In 6th California Islands Symposium, Institute for Wildlife Studies, Ventura, CA. 2005.

Taylor, M. Scott. "Buffalo Hunt: International Trade and the Virtual Extinction of the North American Bison." American Economic Review 101, no. 7 (2011): 3162-195. doi:10.1257/aer.101.7.3162.

"World-Herald editorial: Bison are a fitting symbol for Plains, U.S." Omaha.com. May 18, 2016. Accessed December 10, 2017. http://www.omaha.com/opinion/world-herald-editorial-bison-are-a-fitting-symbol-for-plains/article_c6f22d14-e8a6-5f3a-9c30-b043011909b3.html.

Danz, Harold P. Of Bison and Man: From the Annals of a Bison Yesterday to a Refreshing Outcome from Human Involvement with America's Most Valiant of Beasts. Niwot: University Press of Colorado, 1997.

Derr, James N., Philip W. Hedrick, Natalie D. Halbert, Louis Plough, Lauren K. Dobson, Julie King, Calvin Duncan, David L. Hunter, Noah D. Cohen, and Dennis Hedgecock. "Phenotypic Effects of Cattle Mitochondrial DNA in American Bison." Conservation Biology 26, no. 6 (2012): 1130-136. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2012.01905.x.

Flannery, Tim F. The Eternal Frontier: An Ecological History of North America and Its Peoples. London: Penguin, 2001.

Geist, Valerius. Buffalo nation: history and legend of the North American bison. Stillwater, MN: Voyageur Press, 1996.

Hansen, Sarah Baker. "Nebraska Man Raises Organic Bison." Omaha World-Herald, September 17, 2017. Accessed November 7, 2017. https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/nebraska/articles/2017-09-17/nebraska-man-raises-organic-bison.

Harris, H. R. ""John Full of Pep," Only Surviving Paleface to Hunt Buffaloes with Pawnees, Recalls Days when Hoof Beats Resembled Thunder on Plains." The Omaha Sunday Bee, August 29, 1920. Accessed December 10, 2017.

Hedrick, Philip W. “Conservation Genetics and North American Bison.” Journal of Heredity 100, no. 4 (July 2009): 411-420. doi:10.1093/jhered/esp024

Isenberg. The Destruction of the Bison: An Environmental History, 1750-1920 (Studies in Environment and History). Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Knapp, A., J. Blair, J. Briggs, S. Collins, D. Hartnett, L. Johnson, and E. Towne. "The Keystone Role of Bison in North American Tallgrass Prairie: Bison Increase Habitat Heterogeneity and Alter a Broad Array of Plant, Community, and Ecosystem Processes."BioScience, 1999. doi:10.1525/bisi.1999.49.1.39.

Lott, Dale F. American Bison: a Natural History. University of California Press, 2003.

McHugh, Tom. The Time of the Buffalo. New Jersey: Castle Books, 2004.

Popper, Deborah E., and Frank J. Popper. "The onset of the Buffalo Commons." Journal of the West 45, no. 2 (2006): 29.

Ray, Arthur J. Indians in the Fur Trade: their roles as trappers, hunters, and middlemen in the lands southwest of hudson bay, 1660-1870. Toronto: Univ of Toronto Press, 2017.

Smits, David D. "The Frontier Army and the Destruction of the Buffalo: 1865-1883." The Western Historical Quarterly 25, no. 3 (1994): 312. doi:10.2307/971110.

Sweitzer, RICK A., Juanita M. Constible, Dirk H. Van Vuren, PETER T. Schuyler, and FRANK R. Starkey. "History, habitat use and management of bison on Catalina Island, California." In 6th California Islands Symposium, Institute for Wildlife Studies, Ventura, CA. 2005.

Taylor, M. Scott. "Buffalo Hunt: International Trade and the Virtual Extinction of the North American Bison." American Economic Review 101, no. 7 (2011): 3162-195. doi:10.1257/aer.101.7.3162.

"World-Herald editorial: Bison are a fitting symbol for Plains, U.S." Omaha.com. May 18, 2016. Accessed December 10, 2017. http://www.omaha.com/opinion/world-herald-editorial-bison-are-a-fitting-symbol-for-plains/article_c6f22d14-e8a6-5f3a-9c30-b043011909b3.html.

Publisher

The Durham Museum Collection

Collection

Citation

Chelsey Dizon

Kevin Vincent, “Bison,” Omaha in the Anthropocene, accessed April 18, 2024, https://steppingintothemap.com/anthropocene/items/show/6.

Embed

Copy the code below into your web page