ConAgra Foods

Title

ConAgra Foods

Subject

The foods here are part of the ConAgra product line. They all contain genetically modified organisms (GMOs) in the form of corn products, like corn starch. For centuries, people have changed plants to improve farming through artificial selection. Working the land and farming plants as food is one way that people interact with the environment. In the past, people did this by choosing the seeds from the best plants to grow the next year. Now, people use a different method called genetic modification. In the past, companies like ConAgra have used this method to make their food tastier and easier to make. ConAgra has recently decided to remove GMOs from their food due to public opinion. This shift away from GMOs signals the start of another new chapter in food production. Because ConAgra is a part of that change, it represents the way food production has shaped the environment.

Description

The Anthropogenic "object" that will be the focus of this essay is the currently Omaha-based corporation ConAgra. This corporation was founded in 1919 in Nebraska after the consolidation of four smaller grain mills, with the headquarters moving to Omaha itself in 1922. Since then it has steadily built up into the larger conglomerate that it is today, growing into a strong local and global presence, with offices in the United States, Canada, Mexico, and Italy. ConAgra has had a major impact on the legislation that Omaha has passed in relation to businesses, with the company receiving tax breaks for investing in its own city, rather than moving away. (Larson, 2007) Its political clout and extensive lobbying, along with the large number of citizens of Omaha that it employs, have made it a major player in Omaha's involvement with the Anthropocene. Moreover, the purpose of this Anthropogenic artifact lies mainly in consumption as a food product and occupation as a major employer.

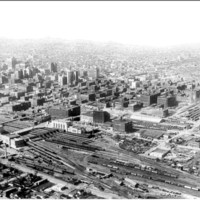

ConAgra Foods is part of The Durham’s collection because of its long history as an influential corporation in Omaha. Starting just outside of the city in Grand Island, Nebraska, ConAgra moved its headquarters to Omaha during their early years, where it has remained since, employing thousands, shaping the landscape of the city and its legislature. One of the best examples of the direct impact ConAgra Foods has had on the landscape of Omaha is the renovation of Jobber’s Canyon on the riverfront. These changes, which removed long-standing warehouse buildings that constituted a proposed historic district at the time, were part of the larger “Return to the River” movement that began in the 1980s and lasted through the early 2000s that saw a rise in renovations of the riverfront to include parks, corporate office campuses, and other recreational areas. (Bednarek, 2009) ConAgra was able to make this happen through the city’s desire to have the corporation remain located in Omaha due to the large number of people the company employs locally. In this sense, ConAgra Foods is unique to Omaha, though it has since expanded to be a major national and global presence as part of a growing commercialization of food distribution companies on a global scale. This Omaha-native company has interacted with the people of Omaha since its founding, providing food services and consumer products like Peter Pan Peanut Butter, Marie Callender’s meals, and Healthy Choice meals while providing jobs for many of the citizens of Omaha. In the end, ConAgra foods has shaped the history of Omaha in both a recreational and occupational sense, playing a major role in employing some of the local workforce and an even larger role in the distribution of food. Their economic and political position place them as a major force within the Anthropocene in Omaha.

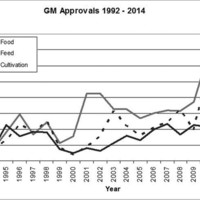

ConAgra is a major player in the Anthropocene as it relates to Omaha, especially through its legislative authority. As the Anthropocene can be examined through the lens of agricultural capitalism and industrialization, ConAgra is easily identifiable as an anthropogenic force of change. One such example is how ConAgra is shaping the views of the public on the use of genetically modified organisms (GMOs). These changes are more varied and perhaps subtler than they initially appear to be. They are currently stating that they are cutting back on the use of GMOs. One explanation for this could be the use of the Public Trust Doctrine to drive legislative changes to protect non-GMO environments, a product of the need to increase profits and keep up with the ever-changing needs of a capitalistic society. (Knudsen, 2011) Other changes seem to appear earlier regarding public opinion about GMOs. Public exposure to biotechnology in general has risen in recent years, starting as early as the late 1990s and rising substantially since. (Runge et al, 2017) At first glance, these two changes appear to be indicative of the ways in which public opinion has modified the GMO policies of ConAgra, but ConAgra Foods, and companies like it, have been just as influential in getting to this point. The rising attention to biotechnology and GMOs in particular has, in the past, driven changes largely focused on the labeling of foods in grocery stores and supermarkets. Essentially, the demand is to know if the food on the shelf is GMO free. This is the obvious, and easy, option for indication of GMOs in stores, especially given the difficulty of passing legislature that would require labeling genetically modified foods – a result of the political and economic clout of companies like ConAgra. (Sunstein, 2017) Simply put, companies like ConAgra want to be able to use cheap and easy materials to make their products, but the market must allow this. If people decide they don’t want to eat GMOs, then ConAgra would want to find a way to sneak them into foods or spend more money producing non-GMO crops. The easiest way to do this is to manipulate the regulations placed on them for labeling their products. Given that non-GMO foods are far less common, and that labeling GMOs would be potentially detrimental to profits, it makes sense for companies like ConAgra to lobby against legislature requiring the labeling of GMOs and to promote the labeling of non-GMO foods as GMO free instead.

ConAgra has proven to be a reactionary force, driving the way the market truly responds to the growing attentiveness of the public regarding the use of GMOs. It can be argued that the Anthropocene begins when humans begin to manipulate the environment for their own benefit, such as with the widespread use of agriculture, and the presence of grain mills. In this case, while the human alteration of food has already taken place, the Anthropogenic impacts are being lessened, or changed in ways that we are not yet aware of, with the reduction of GMO usage by ConAgra, thus discouraging further human exploitation of their environment. (Yang and Chen, 2016) ConAgra’s stance on their reduction of GMO use is unfortunately not presented to the public this way. Instead it is represented as the company listening to the needs and wants of its customers and removing something the public is not sold on.

Another main theme regarding the Anthropocene is the idea of invasion and exploitation of the environment for human gain. ConAgra is arguably one of the largest driving forces for changes in the environment in Omaha, with the destruction of Jobber's Canyon and creation of multiple grain mills for agriculture. (Steffan and Crutzen, 2010) This, along with their commodification of food, contribute to the idea that the Anthropocene is driven by capitalistic forces, as these changes are intrinsically capitalist. (Castree and Rhoads, 2016) The presence of ConAgra in Omaha thus assists in making the Anthropocene a local issue, rather than a far removed one.

ConAgra is still a thriving company to this day, while also expanding their domain internationally and furthering their role in the global commodification of food.(Weis, 2007) Along with this has come the idea that they can get away with breaking the law on multiple different occasions, exploiting the products they are given by other companies to make their foods. (Schlosser, 2001) This readiness to blatantly defy the regulations and exploit the environment for personal and economic gain seems to be typical for a company as large as ConAgra, helping to shape the way that people look at, and interact with, the environment. Instead of using their political prowess and national attention to encourage a healthy relationship with the food they produce and distribute, they have further exemplified the human desire for environmental domination through massive agriculture and underpaying those who provide them with livestock. (Schlosser, 2001) For example, some farmers have accused ConAgra for undercutting the actual weight of the products they purchase in order to ensure a cheap buy.

ConAgra itself is already an international power that contributes to global production and distribution of food. (Bonanno, 1994) They are able to expand the reach of their influence beyond just Omaha and the United States when it comes to how people will view their environment. Due to this, they are furthering the growing tendency to refer to food in terms of nutrition and not as food in and of itself. (Pollan, 2008) Due to the naturally exploitative nature of agriculture and food production it comes as no surprise that ConAgra's global impact on the Anthropocene is reinforcing human's desire and ability to exploit their environment via capitalist agricultural practices. To ensure they thrive as a business they have met the needs and wants of people in different areas and through different times, instead of focusing on the less popular option of monitoring and preserving the environment. It seems, then, that instead of supply reflecting demand, in this case ConAgra has reshaped demand so as to fit a profitable, albeit potentially harmful, supply rather than ceding the point and turning to less exploitative agricultural methods. In order for ConAgra to become a more positive driving force in the Anthropocene they would need to participate in the restructuring of capitalistic thought surrounding food. (Tickell, 2011) Instead of simply commodifying their products to fit the exact market demand, they would have to shift their focus to be more environmentally centered and conscious.

In a very direct sense, the use of GMOs in the past by ConAgra and companies like it indicates a turning point in the way people affect the ecological status of the Earth. Humans have been altering the genes of plants and animals for thousands of years, mostly through selective breeding. The advent of modern technology, however, has changed the way humans affect the genomes of plants and animals, making the effect humans have on the environment in terms of genetic modification more direct than ever. (Aagaard, 2011; Cooley, 2004; Hourdequin, 2013) While in the past genetic modification relied on organisms inheriting traits from their predecessors, humans can now directly transplant traits into nearly any organism they desire. For example, the majority of soybean growth in the United States relies on soybeans that have been genetically programmed to express their own pesticides. The same is true of corn. The changes forced on these organisms are not alone in scope or purpose; other examples abound. Other crops have been modified to fortify the diets of those who grow and consume them, like golden rice, a common staple food for much of Asia. Golden rice has been genetically modified to produce more vitamin A. (Hourdequin, 2013) While many of these changes are, themselves, benign, they pose potential ecological problems. Most of the genetic modifications given to organisms create a biological advantage for that organism. This advantage, in turn, confers a heightened capacity for reproductive potential, meaning genetically modified organisms often make incredibly efficient invasive species. This is especially true of plants who can spread over wide areas quickly and reproduce on their own. (Pipernoa, 2017) This problem is worsened by the fact that there is almost no way to control for pollen distribution. So, it seems the anthropogenic effects of GMOs exceed the simplistic explanation that tampering directly with the genetic makeup of an organism is indicative of human impacts on the environment, including also the idea that those changes have the capacity to multiply environmental impacts in the form of thewidespread and uncontrolled dispersal of those organisms.

Companies like ConAgra, through their normal responses to market shifts, can affect changes in the environment further proving their status as a product of the Anthropocene. Capitalism is a main driving force behind human-caused environmental changes, as the environment is a rich source of capital for industries. ConAgra acts as a prime example of the capitalist machine through their exploitation of the environment and organisms with genetic modification. They use GMOs to increase food output, increase capital, and use that capital to rework the system in its favor. The redirecting of laws and product identification can affect environmental changes. There is, however, a counterpoint to these arguments, and that is the capacity of such companies to limit the impacts they have on the environment, pursuant to the demand of the market. In other words, while companies like ConAgra have, in the past, been a nexus of environmental change, mostly in a negative way, they can also provide the means by which environmental impacts are mitigated. (Schimelpfenig, 2017; Tickell, 2011)

While ConAgra is not completely in favor of the use of human modification on the environment and food, it has been a major driving force in bringing the Anthropocene to Omaha. Businesses themselves play a very large role in shaping the mindset of how people are to treat the environment, and what kind of environment will be left behind for future generations. ConAgra is leaving a dichotomous legacy of exploitation of the raw environment through massive agriculture conglomerates and of limiting human impact on the food we eat through scaling back on their overall use of GMOs. (Schmidheiny, 1998) This raises the question of how much exploitation is too much regarding humans and their environment, and in relation to the actions of ConAgra, genetically modifying the food we will be directly intaking is where the line is drawn. While it has been questioned whether or not the world before humans is what we should strive to preserve and return to, the concern for over-exploitation has still become more apparent in recent years, especially in the case of large corporations, even with their continued use of massive agriculture.

ConAgra Foods is part of The Durham’s collection because of its long history as an influential corporation in Omaha. Starting just outside of the city in Grand Island, Nebraska, ConAgra moved its headquarters to Omaha during their early years, where it has remained since, employing thousands, shaping the landscape of the city and its legislature. One of the best examples of the direct impact ConAgra Foods has had on the landscape of Omaha is the renovation of Jobber’s Canyon on the riverfront. These changes, which removed long-standing warehouse buildings that constituted a proposed historic district at the time, were part of the larger “Return to the River” movement that began in the 1980s and lasted through the early 2000s that saw a rise in renovations of the riverfront to include parks, corporate office campuses, and other recreational areas. (Bednarek, 2009) ConAgra was able to make this happen through the city’s desire to have the corporation remain located in Omaha due to the large number of people the company employs locally. In this sense, ConAgra Foods is unique to Omaha, though it has since expanded to be a major national and global presence as part of a growing commercialization of food distribution companies on a global scale. This Omaha-native company has interacted with the people of Omaha since its founding, providing food services and consumer products like Peter Pan Peanut Butter, Marie Callender’s meals, and Healthy Choice meals while providing jobs for many of the citizens of Omaha. In the end, ConAgra foods has shaped the history of Omaha in both a recreational and occupational sense, playing a major role in employing some of the local workforce and an even larger role in the distribution of food. Their economic and political position place them as a major force within the Anthropocene in Omaha.

ConAgra is a major player in the Anthropocene as it relates to Omaha, especially through its legislative authority. As the Anthropocene can be examined through the lens of agricultural capitalism and industrialization, ConAgra is easily identifiable as an anthropogenic force of change. One such example is how ConAgra is shaping the views of the public on the use of genetically modified organisms (GMOs). These changes are more varied and perhaps subtler than they initially appear to be. They are currently stating that they are cutting back on the use of GMOs. One explanation for this could be the use of the Public Trust Doctrine to drive legislative changes to protect non-GMO environments, a product of the need to increase profits and keep up with the ever-changing needs of a capitalistic society. (Knudsen, 2011) Other changes seem to appear earlier regarding public opinion about GMOs. Public exposure to biotechnology in general has risen in recent years, starting as early as the late 1990s and rising substantially since. (Runge et al, 2017) At first glance, these two changes appear to be indicative of the ways in which public opinion has modified the GMO policies of ConAgra, but ConAgra Foods, and companies like it, have been just as influential in getting to this point. The rising attention to biotechnology and GMOs in particular has, in the past, driven changes largely focused on the labeling of foods in grocery stores and supermarkets. Essentially, the demand is to know if the food on the shelf is GMO free. This is the obvious, and easy, option for indication of GMOs in stores, especially given the difficulty of passing legislature that would require labeling genetically modified foods – a result of the political and economic clout of companies like ConAgra. (Sunstein, 2017) Simply put, companies like ConAgra want to be able to use cheap and easy materials to make their products, but the market must allow this. If people decide they don’t want to eat GMOs, then ConAgra would want to find a way to sneak them into foods or spend more money producing non-GMO crops. The easiest way to do this is to manipulate the regulations placed on them for labeling their products. Given that non-GMO foods are far less common, and that labeling GMOs would be potentially detrimental to profits, it makes sense for companies like ConAgra to lobby against legislature requiring the labeling of GMOs and to promote the labeling of non-GMO foods as GMO free instead.

ConAgra has proven to be a reactionary force, driving the way the market truly responds to the growing attentiveness of the public regarding the use of GMOs. It can be argued that the Anthropocene begins when humans begin to manipulate the environment for their own benefit, such as with the widespread use of agriculture, and the presence of grain mills. In this case, while the human alteration of food has already taken place, the Anthropogenic impacts are being lessened, or changed in ways that we are not yet aware of, with the reduction of GMO usage by ConAgra, thus discouraging further human exploitation of their environment. (Yang and Chen, 2016) ConAgra’s stance on their reduction of GMO use is unfortunately not presented to the public this way. Instead it is represented as the company listening to the needs and wants of its customers and removing something the public is not sold on.

Another main theme regarding the Anthropocene is the idea of invasion and exploitation of the environment for human gain. ConAgra is arguably one of the largest driving forces for changes in the environment in Omaha, with the destruction of Jobber's Canyon and creation of multiple grain mills for agriculture. (Steffan and Crutzen, 2010) This, along with their commodification of food, contribute to the idea that the Anthropocene is driven by capitalistic forces, as these changes are intrinsically capitalist. (Castree and Rhoads, 2016) The presence of ConAgra in Omaha thus assists in making the Anthropocene a local issue, rather than a far removed one.

ConAgra is still a thriving company to this day, while also expanding their domain internationally and furthering their role in the global commodification of food.(Weis, 2007) Along with this has come the idea that they can get away with breaking the law on multiple different occasions, exploiting the products they are given by other companies to make their foods. (Schlosser, 2001) This readiness to blatantly defy the regulations and exploit the environment for personal and economic gain seems to be typical for a company as large as ConAgra, helping to shape the way that people look at, and interact with, the environment. Instead of using their political prowess and national attention to encourage a healthy relationship with the food they produce and distribute, they have further exemplified the human desire for environmental domination through massive agriculture and underpaying those who provide them with livestock. (Schlosser, 2001) For example, some farmers have accused ConAgra for undercutting the actual weight of the products they purchase in order to ensure a cheap buy.

ConAgra itself is already an international power that contributes to global production and distribution of food. (Bonanno, 1994) They are able to expand the reach of their influence beyond just Omaha and the United States when it comes to how people will view their environment. Due to this, they are furthering the growing tendency to refer to food in terms of nutrition and not as food in and of itself. (Pollan, 2008) Due to the naturally exploitative nature of agriculture and food production it comes as no surprise that ConAgra's global impact on the Anthropocene is reinforcing human's desire and ability to exploit their environment via capitalist agricultural practices. To ensure they thrive as a business they have met the needs and wants of people in different areas and through different times, instead of focusing on the less popular option of monitoring and preserving the environment. It seems, then, that instead of supply reflecting demand, in this case ConAgra has reshaped demand so as to fit a profitable, albeit potentially harmful, supply rather than ceding the point and turning to less exploitative agricultural methods. In order for ConAgra to become a more positive driving force in the Anthropocene they would need to participate in the restructuring of capitalistic thought surrounding food. (Tickell, 2011) Instead of simply commodifying their products to fit the exact market demand, they would have to shift their focus to be more environmentally centered and conscious.

In a very direct sense, the use of GMOs in the past by ConAgra and companies like it indicates a turning point in the way people affect the ecological status of the Earth. Humans have been altering the genes of plants and animals for thousands of years, mostly through selective breeding. The advent of modern technology, however, has changed the way humans affect the genomes of plants and animals, making the effect humans have on the environment in terms of genetic modification more direct than ever. (Aagaard, 2011; Cooley, 2004; Hourdequin, 2013) While in the past genetic modification relied on organisms inheriting traits from their predecessors, humans can now directly transplant traits into nearly any organism they desire. For example, the majority of soybean growth in the United States relies on soybeans that have been genetically programmed to express their own pesticides. The same is true of corn. The changes forced on these organisms are not alone in scope or purpose; other examples abound. Other crops have been modified to fortify the diets of those who grow and consume them, like golden rice, a common staple food for much of Asia. Golden rice has been genetically modified to produce more vitamin A. (Hourdequin, 2013) While many of these changes are, themselves, benign, they pose potential ecological problems. Most of the genetic modifications given to organisms create a biological advantage for that organism. This advantage, in turn, confers a heightened capacity for reproductive potential, meaning genetically modified organisms often make incredibly efficient invasive species. This is especially true of plants who can spread over wide areas quickly and reproduce on their own. (Pipernoa, 2017) This problem is worsened by the fact that there is almost no way to control for pollen distribution. So, it seems the anthropogenic effects of GMOs exceed the simplistic explanation that tampering directly with the genetic makeup of an organism is indicative of human impacts on the environment, including also the idea that those changes have the capacity to multiply environmental impacts in the form of thewidespread and uncontrolled dispersal of those organisms.

Companies like ConAgra, through their normal responses to market shifts, can affect changes in the environment further proving their status as a product of the Anthropocene. Capitalism is a main driving force behind human-caused environmental changes, as the environment is a rich source of capital for industries. ConAgra acts as a prime example of the capitalist machine through their exploitation of the environment and organisms with genetic modification. They use GMOs to increase food output, increase capital, and use that capital to rework the system in its favor. The redirecting of laws and product identification can affect environmental changes. There is, however, a counterpoint to these arguments, and that is the capacity of such companies to limit the impacts they have on the environment, pursuant to the demand of the market. In other words, while companies like ConAgra have, in the past, been a nexus of environmental change, mostly in a negative way, they can also provide the means by which environmental impacts are mitigated. (Schimelpfenig, 2017; Tickell, 2011)

While ConAgra is not completely in favor of the use of human modification on the environment and food, it has been a major driving force in bringing the Anthropocene to Omaha. Businesses themselves play a very large role in shaping the mindset of how people are to treat the environment, and what kind of environment will be left behind for future generations. ConAgra is leaving a dichotomous legacy of exploitation of the raw environment through massive agriculture conglomerates and of limiting human impact on the food we eat through scaling back on their overall use of GMOs. (Schmidheiny, 1998) This raises the question of how much exploitation is too much regarding humans and their environment, and in relation to the actions of ConAgra, genetically modifying the food we will be directly intaking is where the line is drawn. While it has been questioned whether or not the world before humans is what we should strive to preserve and return to, the concern for over-exploitation has still become more apparent in recent years, especially in the case of large corporations, even with their continued use of massive agriculture.

Creator

Patrick Eiden

Brittany Keath

Brittany Keath

Source

Aagaard, Todd S. Environmental Harms, Use Conflicts, and Neutral Baselines in Environmental

Law. Duke Law Journal 60, no. 7 (2011): 1505-564. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23034804.

Aldemita, R., Reaño, R., Solis, I., & Hautea, R. (2015). Trends in global approvals of biotech crops (1992-2014). GM Crops & Food., 6(3), 150-166

Bonanno, Alessandro. From Columbus to ConAgra. Kansas: University of Kansas Press. 1994.

Castree, Noel, and Rhoads, Bruce. A Companion to Environmental Geography. West Sussex:

John Wiley &Sons, Ltd. 2016.

Cooley, D. R. "Transgenic Organisms and Some Legal Ethics." Public Affairs Quarterly 18, no. 2 (2004): 91-110. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40441374.

Crutzen, P., Steffen, W., Williams, M. & Zalasiewicz, J. 2010, ‘The new world of the

anthropocene’, Environmental science and technology viewpoint, vol. 44, no. 7, pp. 2228

2231.

Dryzek, John S. 2016. "Institutions for the Anthropocene: Governance in a Changing Earth

System." British Journal Of Political Science 46, no. 4: 937-956. Historical Abstracts,

EBSCOhost (accessed October 10, 2017).

Hourdequin, Marion. "Restoration and History in a Changing World: A Case Study in Ethics for

the Anthropocene." Ethics and the Environment 18, no. 2 (2013): 115-34.

Janet R Daly Bednarek, “Creating an ‘Image Center’: Reimagining Omaha’s Downtown and Riverfront, 1986-2003,” Nebraska History 90 (2009): 190-207

Knudsen, Guy R. "Impacts of Agricultural GMOs on Wildlands: A New Frontier of Biotech Litigation." Natural Resources & Environment 26, no. 1 (2011): 13-17. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23054894.

Larson, Lawrence, Cottrell, Barbara, Dalstrom, Harl, and Dalstrom, Kay Calamé. Upstream

Metropolis: An Urban Biography of Omaha and Council Bluffs. University of Nebraska

Press, 2007. 342-401.

Pipernoa, Dolores R. 2017. "Assessing elements of an extended evolutionary synthesis for plant domestication and agricultural origin research." Proceedings Of The National Academy Of Sciences Of The United States Of America 114, no. 25: 6429-6437. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed November 20, 2017).

Pollan, Michael. In Defense of Food. New York: Penguin Press, 2008.

Runge, Kristen K., Dominique Brossard, Dietram A. Sheufele, Kathleen M. Rose, and Brita J. Larson. 2017. “The Polls-Trends Attitudes About Food and Food-Related Biotechnology.” Public Opinion Quarterly 81, no. 2:577-596. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed November 8, 2017).

Schimelpfenig, Robert. 2017. "The Drama of the Anthropocene: Can Deep Ecology,

Romanticism, and Renaissance Science Rebalance Nature and Culture?." American

Journal Of Economics & Sociology 76, no. 4: 821-1081. Historical Abstracts,

EBSCOhost (accessed October 10, 2017).

Schlosser, Eric. Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal. Boston: Houghton

Mifflin Company. 2001.

Schmidheiny, Stephan. Changing Course: A global business perspective on development and the environment. London: The MIT Press. 1998.

Sunstein, Cass R. 2017. “On Mandatory Labeling, With Special Reference to Genetically Modified Foods.” University of Pernnsylvania Law Review 165, no. 5:1043-1095. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed November 8, 2017).

Tickell, Crispin. "Societal Responses to the Anthropocene. "Philosophical Transactions:

Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 369, no. 1938 (2011): 926-32.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/41061707.

Weis, Anthony J. The Global Food Economy: The Battle for the Future of Farming.

Canada: Fernwood Publishing, 2007.

Yang, y. Tony, and Brian Chen. 2016. “Governing GMOs in the USA: science, law and public health.” Journal Of The Science Of Food & Agriculture 96, no. 6:1851-1855. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed November 8, 2017).

Law. Duke Law Journal 60, no. 7 (2011): 1505-564. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23034804.

Aldemita, R., Reaño, R., Solis, I., & Hautea, R. (2015). Trends in global approvals of biotech crops (1992-2014). GM Crops & Food., 6(3), 150-166

Bonanno, Alessandro. From Columbus to ConAgra. Kansas: University of Kansas Press. 1994.

Castree, Noel, and Rhoads, Bruce. A Companion to Environmental Geography. West Sussex:

John Wiley &Sons, Ltd. 2016.

Cooley, D. R. "Transgenic Organisms and Some Legal Ethics." Public Affairs Quarterly 18, no. 2 (2004): 91-110. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40441374.

Crutzen, P., Steffen, W., Williams, M. & Zalasiewicz, J. 2010, ‘The new world of the

anthropocene’, Environmental science and technology viewpoint, vol. 44, no. 7, pp. 2228

2231.

Dryzek, John S. 2016. "Institutions for the Anthropocene: Governance in a Changing Earth

System." British Journal Of Political Science 46, no. 4: 937-956. Historical Abstracts,

EBSCOhost (accessed October 10, 2017).

Hourdequin, Marion. "Restoration and History in a Changing World: A Case Study in Ethics for

the Anthropocene." Ethics and the Environment 18, no. 2 (2013): 115-34.

Janet R Daly Bednarek, “Creating an ‘Image Center’: Reimagining Omaha’s Downtown and Riverfront, 1986-2003,” Nebraska History 90 (2009): 190-207

Knudsen, Guy R. "Impacts of Agricultural GMOs on Wildlands: A New Frontier of Biotech Litigation." Natural Resources & Environment 26, no. 1 (2011): 13-17. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23054894.

Larson, Lawrence, Cottrell, Barbara, Dalstrom, Harl, and Dalstrom, Kay Calamé. Upstream

Metropolis: An Urban Biography of Omaha and Council Bluffs. University of Nebraska

Press, 2007. 342-401.

Pipernoa, Dolores R. 2017. "Assessing elements of an extended evolutionary synthesis for plant domestication and agricultural origin research." Proceedings Of The National Academy Of Sciences Of The United States Of America 114, no. 25: 6429-6437. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed November 20, 2017).

Pollan, Michael. In Defense of Food. New York: Penguin Press, 2008.

Runge, Kristen K., Dominique Brossard, Dietram A. Sheufele, Kathleen M. Rose, and Brita J. Larson. 2017. “The Polls-Trends Attitudes About Food and Food-Related Biotechnology.” Public Opinion Quarterly 81, no. 2:577-596. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed November 8, 2017).

Schimelpfenig, Robert. 2017. "The Drama of the Anthropocene: Can Deep Ecology,

Romanticism, and Renaissance Science Rebalance Nature and Culture?." American

Journal Of Economics & Sociology 76, no. 4: 821-1081. Historical Abstracts,

EBSCOhost (accessed October 10, 2017).

Schlosser, Eric. Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal. Boston: Houghton

Mifflin Company. 2001.

Schmidheiny, Stephan. Changing Course: A global business perspective on development and the environment. London: The MIT Press. 1998.

Sunstein, Cass R. 2017. “On Mandatory Labeling, With Special Reference to Genetically Modified Foods.” University of Pernnsylvania Law Review 165, no. 5:1043-1095. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed November 8, 2017).

Tickell, Crispin. "Societal Responses to the Anthropocene. "Philosophical Transactions:

Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 369, no. 1938 (2011): 926-32.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/41061707.

Weis, Anthony J. The Global Food Economy: The Battle for the Future of Farming.

Canada: Fernwood Publishing, 2007.

Yang, y. Tony, and Brian Chen. 2016. “Governing GMOs in the USA: science, law and public health.” Journal Of The Science Of Food & Agriculture 96, no. 6:1851-1855. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed November 8, 2017).

Rights

The Durham Museum Collections

Collection

Citation

Patrick Eiden

Brittany Keath, “ConAgra Foods,” Omaha in the Anthropocene, accessed April 16, 2024, https://steppingintothemap.com/anthropocene/items/show/8.

Embed

Copy the code below into your web page