About

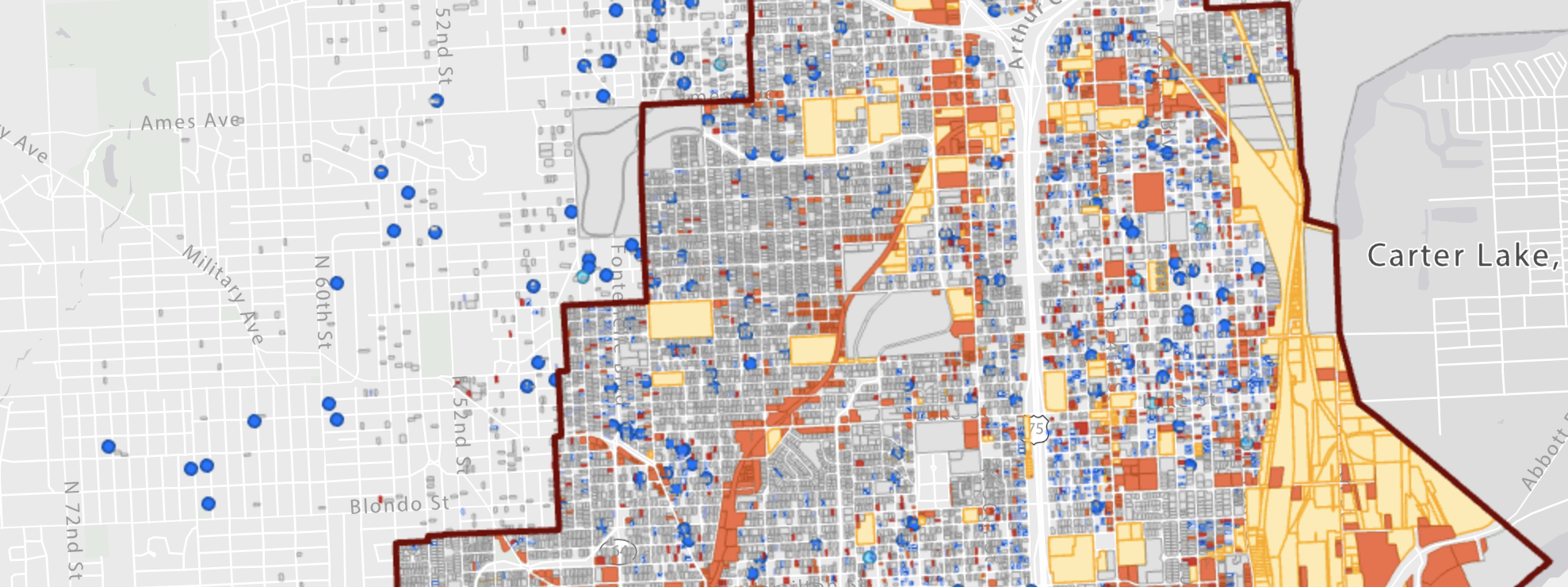

In January 2018, the Omaha World Herald published a retrospective on the previous two decades of lead remediation work in the city. City officials, non-profits, and EPA representatives expressed optimism about their successes, while acknowledging the continued seriousness of lead exposure in large areas of eastern Omaha. To date, the city has spent approximately 3.2 million dollars cleaning residential properties, including soil testing and replacement and stabilizing lead paint on the exteriors of homes. Asked for her comments, Mayor Jean Stothert commended the progress, but also noted that “I do think it’s important that we keep up with what we’re doing, because obviously it is a public health priority,” “It’s about the safety of our children and families and it’s about safe and healthy housing.” The EPA designated eastern Omaha a Superfund site because of Omaha’s industrial history of lead, but Stothert’s comments remind us that the most vulnerable populations have historically been children and the most vulnerable regions have been residential. By all accounts, progress has been real, if incomplete. Children’s blood-lead levels have dropped from a high of 33 percent with elevated blood lead levels before 1998 to less than 2 percent in 2015. Although 300 properties have been delisted, this accounts for only 11 percent on the superfund list. Today, the Omaha Lead Superfund project remains that largest residential lead pollution site in the country.

This article also reminds us how little we know about the history of lead exposure, including which populations have been disproportionately exposed to lead pollution. This is surprising because a large body of government studies as well as work in geography, history, and public health have demonstrated that environmental and industrial hazards like lead are never evenly distributed. Environmental justice scholarship work built upon grassroots activism in the 1970s and 80s that called attention to the differential vulnerability of minority populations to environmental hazards, particularly toxic waste and industrial pollution. This environmental justice movement worked at the intersection of civil rights and environmental activism and in the past two decades, fundamentally reshaped the discourses of each. Much work remains, however. In the wake of quick onset disasters like hurricanes or earthquakes, or amidst the slow violence of industrial waste exposure, one is still more likely to hear people ask “how much” a disaster costs and “how many” were exposed, than “who” was affected and “why?” In Omaha, in the case of lead, history informs these important questions.

This project focuses on the who and why of lead exposure using a combination of geographical and historical methods. Determining who was exposed to pollution and why are spatial/historical questions that require digging deep into the metropolitan history of Omaha. This project builds to considerable extent on the work of historian Leif Fredrickson and his work on the history of lead in Baltimore. It doesn’t pretend to offer a complete set of answers, rather, it is intended to open new avenues of inquiry into the relationship between inequality and environmental vulnerability in Omaha. It does this by exploring six themes relevant to the story of lead pollution in Omaha: exposure to leaded gasoline (tetraethyl lead), residential exposure to lead paint, industrial exposure to lead particulates, the history of public health, the history of the Superfund site, and the history of metropolitan development in Omaha.