Spanish Silver Reales

Title

Spanish Silver Reales

Subject

Birthed from Spanish mined “New World “silver, the Spanish Reales coins became the first global currency. The coins united 16th century economies across the world by providing a universal system of value. Soon, businessmen oceans apart could trade with confidence, opening ports from Shanghai to Peru. Yet, the Reales’ effects were not confined to trade alone. Global currency allowed exponential business growth, shifting the human-nature relationship. Instead of seeing value in nature itself, nature became worth what it could produce for the economy. Natural areas were only valuable because they could be either mined, farmed, or logged. And so, few ecosystems have remained unaffected by humans. But, human society has begun to realize the danger of this mindset and is turning to a more sustainable coexistence with nature.

Description

Upon first glance at Bryon Reed’s Spanish Reales, it may be tempting to assign little significance to these silver coins. They are relatively small, light, and devoid of ostentatious ornamentation. (Figure 1 and Figure 2) They are perhaps one of a billion other coins that share their name. It would certainly seem that, attributing events as monumental as the rise of globalization and the beginning of the Anthropocene, an age of dramatic human influence on the earth systems, to such inconsequential objects would be absurd. Likewise, connecting these coins of the Spanish empire to the history of Omaha, Nebraska, a gateway city to the American west seems unreasonable at best. We argue, however, that these coins have a very consequential story to tell, one that connects continents and spans hundreds of years. It was no coincidence that these Spanish coins found their way to Omaha, a city thousands of miles from where they were mined and processed.

The story of these coins is one of two parallel historical developments. First, the story of globalization and the silver trade. Founded in the 16th century, the silver trade birthed the globalization of expansive production frontiers, where the exploitation of cheap nature fueled capital accumulation. A second, parallel story tells the history of the United States frontier in the nineteenth century. That historical moment brought these coins to Omaha, itself a product of a new, American commodity frontier, this time in land. The real estate mogul Byron Reed connects these narratives. The story of these silver coins begins in 1492 with the Spanish kingdom’s expansion into the New World. Prior to this date, global communities displayed a pattern of relatively even development, characterized by similar forms of production, urbanization, large scale movements, social structures and economic development (J. Blaut, 1992). Often feudal in nature, the economic organization of these communities seem a far cry from those of the modern world system (J. Blaut, 1976). On the other side of 1492, the opposite quickly became true. While subsistence and survival characterized mankind’s exploitative relationship with nature prior to the Spanish’s conquest, an insatiable thirst for capital has fueled subsequent and increasingly expansive interactions with our environment (J. Moore, 2010). Commodity frontiers, areas where cheap land and labor lent themselves to capital accumulation, quickly became coveted resources. The silver frontier of Bolivia, appropriated shortly after the Spanish discovery of the New World, holds a unique spot in history as one of the first and most influential commodity frontiers the world has ever seen (J. Moore, 2007).

Prior to the Spanish 1545 conquest of Potosi, the indigenous inhabitants primarily practiced an agricultural way of life, similar in character to their European counterparts (J. Moore, 2010 and R. Barragán, 2017). More significant to the Spanish was the indigenous mining activities at Cerro Rico, “the rich mountain of silver.” A geological anomaly, the mountain, whose slopes rose above the small community of Potosi, quickly became the greatest single source of silver in global history (O. S. Arce-Burgoa and R. Goldfarb, 2009). Native Bolivians extracted silver prior to the Spanish conquest, however, with the Incan kings representing the primary source of demand, the ore’s market remained relatively small, effectively regulating its environmental impact (R. Barragán, 2017). The Spanish invasion of the city profoundly altered Potosi’s relationship with its environment and thrust it into the center of a developing world system.

Feeding an insatiable imperialistic drive while also propping up the failing home economy, the Spanish saw Cerro Rico as their key to continued colonial expansion (J. Moore, 2010 and E. Galeano, 1973). Upon Spanish invasion, Potosi became a swirling hub of activity, not unlike the later boomtowns on the American western frontier. However, instead of agricultural expansion and real estate, an unquenchable Spanish thirst for silver drove Potosi’s expansion. At first profit margins were ample. Massive amounts of silver was mined, refined and converted to silver currency, like the Spanish Reales, before being packed on Spanish Galleons to be shipped across the world. By 1560 the quality of ore began to decline (J. Moore, 2010), yet Spanish pressure to produce ever increasing amounts of silver still persisted. The consequences were catastrophic for native people and the landscape. Forests became merely fuel, natives only a useful source of labor, and the soils served only as a means to supply the energy necessary to sustain the labor (J. Moore, 2010 and R. Barragán, 2017). Collectively they became cogs in a machine, simply a means to an end. The lifeblood of Potosi, its people and its land were commodified and exploited in the name of silver production. With over 60% of the world’s sixteenth century silver output attributed to Potosi (D. O. Flynn and A. Giraldez, 1995), it is hard to argue that this system was not fantastically successful for the Spanish. However, the ecological and human tolls were as devastating as they were obvious. As one early 17th century Spanish observer of Cerro Rico noted, “because the work done on the mountain, there is no sign that it had ever had a forest, when it was discovered it was fully covered with trees… On this mountain, there was also a great amount of hunting…There were also deer, and today not even weeds grow on the mountain, not even in the most fertile soils where trees could have grown (Figure 3) (J. Moore, 2010).” Shattered in succession, the forests, fields and ecosystems in all of modern day Bolivia suffered with Cerro Rico, as the height of the Spanish silver frontier necessitated expansive, unsustainable agriculture and a 200 mile ring of deforestation centered on Potosi. Eventually, the rich veins of Cerro Rico dried to a trickle and the Spanish moved on to the new silver frontiers of colonial Mexico. The silver of Potosi, however, paved the way for a new global epoch, the Anthropocene (A. Jorgenson and E. Kick, 2003).

Understanding the subsequent rise of the Anthropocene, in the face of mass silver production requires a shift of focus from Bolivia, to China. China was the largest, wealthiest civilization of the early modern period. Yet, to the Spanish, it was also frustratingly difficult to trade with (D. O. Flynn and A. Giraldez, 2002). Focused on self-sufficiency, the Chinese viewed western products as wholly unnecessary to their continued success. However, silver’s rapid emergence onto the global stage in the 16th and 17th century quickly dismantled these constraints to globalization. In China, an unstable 16th century economy, plagued by extreme hyperinflation of paper money, led to a drastic “silveration” movement of the state (D. O. Flynn and A. Giraldez, 2002 and W. Schell, 2001). At precisely the moment that Potosi opened its veins to Spanish mining, silver became the most highly sought commodity in China, effectively terminating the Chinese boycott of European trade (D. O. Flynn and A. Giraldez, 2002).

While silver was opening the ports of China to European trade, it was simultaneously expanding Europe’s once limited commodity frontiers. Before silver’s rise, the lack of a physically backed, universally acknowledged system of value had hindered long distance, expansive resource extraction. However, silver’s arrival onto the scene solved these problems (J. Moore, 2010). Providing investors and borrowers alike the financial security necessary to facilitate extended resource commodification, silver ushered in a new era of vast ecological resource use (J. Moore, 2010). Suddenly, colonial powers began to view their available land and labor as forms of cheap nature to be exploited for the accumulation of wealth. Modeled after the Potosi silver frontier, Europeans took a hold of this new mindset, and in applying it to their iron, timber, agriculture industries, began to fundamentally alter their surrounding environments (J. Moore, 2017). Consequently, an explosive extension of environmental commodification ensued, engulfing nature on a global scale, and devouring 19th century Omaha and the United States western front in its wake.

Exploring the spread of production oriented industry to

Omaha is essential to understanding the linkage between the “gateway city to the west,” Byron Reed, and the 16th century silver trade from which the early pioneer’s silver Reales originated. Born in East Darien, New York, in 1829, and later forced to move west with his parents in 1842 (Western Heritage Museum: Byron Reed Exhibit Pamphlet, 1985), Byron Reed was emblematic of the mid-19th century American western frontier pioneer. Filled with a passion for adventure and excitement, he made his way through his early twenties working in the telegraph industry and later as a Civil War reporter, a job which nearly cost him his life (Omaha Sunday World-Herald, June 7, 1891). Consequently, and perhaps wisely, he left the reporting business, and moved to Omaha, Nebraska in March of 1856.

Omaha in 1856 was a small town, with a population just over 200 people. However, with the growing river trade industry of the time, the community’s location on the Missouri river, lent to the town an immense potential for growth. Sensing an opportunity, Reed, chose to settle down and began to acquire land, which he then sold through his business, The Bryon Reed Real Estate Company, the first of its kind in town (Bryon Reed Company Inc: The Story of Omaha, 1956). Subsequently, officials recruited him to survey much of the city, and soon he became known as Omaha’s authority on land transfers. A few short years later the city would boom upon, not the increasing growth of river trade, but instead the back of Lincoln’s 1862 Pacific Railway Act. The proclamation placed Omaha as the central hub of this new ribbon of steel, and with the rail line’s construction in 1863 (J. Brown, 2012), it solidified the city as, “the gateway city to the west.” Soon after, Omaha became the heart from which these wealth conveying railroads flowed. With the completion of these early railroad lines, including the Union Pacific, Burlington and Quincy, and the Chicago-Rock Island and Pacific, subsequent immigration quickly amplified, spurred by news of early pioneers’ successes and cheap government subsidized land (X. Duran, 2013). Consequently, urbanization trailed closely in its wake, abetting the rampant commodification of the western frontier and the rise of real estate industry.

Fighting for a premium position upon the 19th century world stage, the United States engaged in increasingly expansive trade policies and practices in order to compete with strengthening global competition (A. Menard, 2011). The Pacific Railway Act of 1862, a component of this political platform, was seen as an essential element to the United States success, with its railroads serving as the cornerstone linkages in expanding American trade (W. Webb, 1931 and X. Duran, 2013) . However, the rail lines quickly became more than a means to traverse the vast expanses of the Midwest. Previously unexploited, the tall grass prairies of the American western front, overflowing with rich natural resources, epitomized cheap nature worthy of great exploitation. Access though, had long been problematic, limiting the tremendous potential for capital accumulation (R. Billington, 1974). The expansion of these nineteenth century railroads, however, essentially resolved the access problems, simultaneously pulling the American economy and millions of settlers westward into a new frontier. Consequently, the resources necessary to extract the riches of prairie ecosystems were suddenly at the very fingertips of the early migrating farmers, igniting an agricultural boom. The once virgin Midwestern soils were busted, fertilized, cultivated, and commodified, with exceptional wealth materializing at the expense of nature. Skyrocketing land values in the late 19th century Midwest exemplify this sudden explosion of capital potential, with railroad centered lands of the Nebraska and Kansas territories exhibiting average price increases of $3.10 per acre upon railroad completion, representing a 24% rise in value (C. S. Decker and D. T. Flynn, 2007).

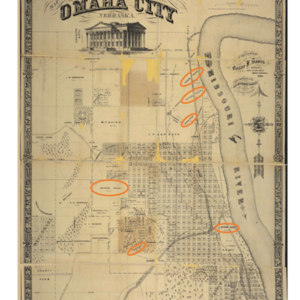

As a result of these changes, Omaha’s industry and population exploded, and Reed, who had amassed a good deal of land around and outside the city prior to the railroads’ arrival (Figure 4), quickly became a wealthy man. Whether selling urban property, or rural agriculture, the once virgin and untouched land which Reed dealt became fundamentally altered and commodified in the wake of the new frontiers arrival. Simultaneously, Reed became an actor and benefactor of the capitally driven western commodity frontier. Not unlike the many other 1850’s and 1860’s American western migrants who saw their fortunes soar with the development of the western frontier (J. Stewart, 2006), Reed was soon worth over an estimated two million dollars. Buoyed by his sudden wealth, he continued to collect land throughout his life, affirmed by the large number of city plots, the additions, and more than 350 acres of farmland he possessed at the time of his death (M. Brown, 1989 and Omaha Sunday World-Herald, June 7, 1891). However, his collection interests expanded beyond land alone. Fascinated by coins, Reed accumulated one of the finest coin collections in the world, in the middle of which sat the Spanish silver Reales, the very piece of history responsible for producing the capitalistic, commodifying, anthropogenic age that made Reed’s collection possible.

While time has muddied the waters between Byron Reed’s Spanish silver and the new human epoch, the Anthropocene, exploring the era’s roots in capitalism and the commodity system crystallizes the distorted relationships. An exemplary western front migrant, Reed built both his reputation and his fortune off this new 19th century commodity frontier. However, while railroads and agriculture, rather than imperialistic lust and mining, characterized the front, its ties to Potosi silver, remain indisputable. Appropriated in the 16th century, Spanish mining of Cerro Rico, the silver mountain, simultaneously became the model, and the agent of change in ushering in a new economic era. Upon this mountain’s rich and mighty slopes, a mindset of production orientation was born, spreading the Spanish silver Reales and paving the way for globalization and intensive nature commodification. Thus, despite their superficial differences, the American western frontier, which delivered Bryon Reed his fortune and his Spanish Reales, fundamentally mirrored its silver 16th century counterpart, both being driven by an insatiable appetite for capital accumulation at the expense of commodified nature.

The story of these coins is one of two parallel historical developments. First, the story of globalization and the silver trade. Founded in the 16th century, the silver trade birthed the globalization of expansive production frontiers, where the exploitation of cheap nature fueled capital accumulation. A second, parallel story tells the history of the United States frontier in the nineteenth century. That historical moment brought these coins to Omaha, itself a product of a new, American commodity frontier, this time in land. The real estate mogul Byron Reed connects these narratives. The story of these silver coins begins in 1492 with the Spanish kingdom’s expansion into the New World. Prior to this date, global communities displayed a pattern of relatively even development, characterized by similar forms of production, urbanization, large scale movements, social structures and economic development (J. Blaut, 1992). Often feudal in nature, the economic organization of these communities seem a far cry from those of the modern world system (J. Blaut, 1976). On the other side of 1492, the opposite quickly became true. While subsistence and survival characterized mankind’s exploitative relationship with nature prior to the Spanish’s conquest, an insatiable thirst for capital has fueled subsequent and increasingly expansive interactions with our environment (J. Moore, 2010). Commodity frontiers, areas where cheap land and labor lent themselves to capital accumulation, quickly became coveted resources. The silver frontier of Bolivia, appropriated shortly after the Spanish discovery of the New World, holds a unique spot in history as one of the first and most influential commodity frontiers the world has ever seen (J. Moore, 2007).

Prior to the Spanish 1545 conquest of Potosi, the indigenous inhabitants primarily practiced an agricultural way of life, similar in character to their European counterparts (J. Moore, 2010 and R. Barragán, 2017). More significant to the Spanish was the indigenous mining activities at Cerro Rico, “the rich mountain of silver.” A geological anomaly, the mountain, whose slopes rose above the small community of Potosi, quickly became the greatest single source of silver in global history (O. S. Arce-Burgoa and R. Goldfarb, 2009). Native Bolivians extracted silver prior to the Spanish conquest, however, with the Incan kings representing the primary source of demand, the ore’s market remained relatively small, effectively regulating its environmental impact (R. Barragán, 2017). The Spanish invasion of the city profoundly altered Potosi’s relationship with its environment and thrust it into the center of a developing world system.

Feeding an insatiable imperialistic drive while also propping up the failing home economy, the Spanish saw Cerro Rico as their key to continued colonial expansion (J. Moore, 2010 and E. Galeano, 1973). Upon Spanish invasion, Potosi became a swirling hub of activity, not unlike the later boomtowns on the American western frontier. However, instead of agricultural expansion and real estate, an unquenchable Spanish thirst for silver drove Potosi’s expansion. At first profit margins were ample. Massive amounts of silver was mined, refined and converted to silver currency, like the Spanish Reales, before being packed on Spanish Galleons to be shipped across the world. By 1560 the quality of ore began to decline (J. Moore, 2010), yet Spanish pressure to produce ever increasing amounts of silver still persisted. The consequences were catastrophic for native people and the landscape. Forests became merely fuel, natives only a useful source of labor, and the soils served only as a means to supply the energy necessary to sustain the labor (J. Moore, 2010 and R. Barragán, 2017). Collectively they became cogs in a machine, simply a means to an end. The lifeblood of Potosi, its people and its land were commodified and exploited in the name of silver production. With over 60% of the world’s sixteenth century silver output attributed to Potosi (D. O. Flynn and A. Giraldez, 1995), it is hard to argue that this system was not fantastically successful for the Spanish. However, the ecological and human tolls were as devastating as they were obvious. As one early 17th century Spanish observer of Cerro Rico noted, “because the work done on the mountain, there is no sign that it had ever had a forest, when it was discovered it was fully covered with trees… On this mountain, there was also a great amount of hunting…There were also deer, and today not even weeds grow on the mountain, not even in the most fertile soils where trees could have grown (Figure 3) (J. Moore, 2010).” Shattered in succession, the forests, fields and ecosystems in all of modern day Bolivia suffered with Cerro Rico, as the height of the Spanish silver frontier necessitated expansive, unsustainable agriculture and a 200 mile ring of deforestation centered on Potosi. Eventually, the rich veins of Cerro Rico dried to a trickle and the Spanish moved on to the new silver frontiers of colonial Mexico. The silver of Potosi, however, paved the way for a new global epoch, the Anthropocene (A. Jorgenson and E. Kick, 2003).

Understanding the subsequent rise of the Anthropocene, in the face of mass silver production requires a shift of focus from Bolivia, to China. China was the largest, wealthiest civilization of the early modern period. Yet, to the Spanish, it was also frustratingly difficult to trade with (D. O. Flynn and A. Giraldez, 2002). Focused on self-sufficiency, the Chinese viewed western products as wholly unnecessary to their continued success. However, silver’s rapid emergence onto the global stage in the 16th and 17th century quickly dismantled these constraints to globalization. In China, an unstable 16th century economy, plagued by extreme hyperinflation of paper money, led to a drastic “silveration” movement of the state (D. O. Flynn and A. Giraldez, 2002 and W. Schell, 2001). At precisely the moment that Potosi opened its veins to Spanish mining, silver became the most highly sought commodity in China, effectively terminating the Chinese boycott of European trade (D. O. Flynn and A. Giraldez, 2002).

While silver was opening the ports of China to European trade, it was simultaneously expanding Europe’s once limited commodity frontiers. Before silver’s rise, the lack of a physically backed, universally acknowledged system of value had hindered long distance, expansive resource extraction. However, silver’s arrival onto the scene solved these problems (J. Moore, 2010). Providing investors and borrowers alike the financial security necessary to facilitate extended resource commodification, silver ushered in a new era of vast ecological resource use (J. Moore, 2010). Suddenly, colonial powers began to view their available land and labor as forms of cheap nature to be exploited for the accumulation of wealth. Modeled after the Potosi silver frontier, Europeans took a hold of this new mindset, and in applying it to their iron, timber, agriculture industries, began to fundamentally alter their surrounding environments (J. Moore, 2017). Consequently, an explosive extension of environmental commodification ensued, engulfing nature on a global scale, and devouring 19th century Omaha and the United States western front in its wake.

Exploring the spread of production oriented industry to

Omaha is essential to understanding the linkage between the “gateway city to the west,” Byron Reed, and the 16th century silver trade from which the early pioneer’s silver Reales originated. Born in East Darien, New York, in 1829, and later forced to move west with his parents in 1842 (Western Heritage Museum: Byron Reed Exhibit Pamphlet, 1985), Byron Reed was emblematic of the mid-19th century American western frontier pioneer. Filled with a passion for adventure and excitement, he made his way through his early twenties working in the telegraph industry and later as a Civil War reporter, a job which nearly cost him his life (Omaha Sunday World-Herald, June 7, 1891). Consequently, and perhaps wisely, he left the reporting business, and moved to Omaha, Nebraska in March of 1856.

Omaha in 1856 was a small town, with a population just over 200 people. However, with the growing river trade industry of the time, the community’s location on the Missouri river, lent to the town an immense potential for growth. Sensing an opportunity, Reed, chose to settle down and began to acquire land, which he then sold through his business, The Bryon Reed Real Estate Company, the first of its kind in town (Bryon Reed Company Inc: The Story of Omaha, 1956). Subsequently, officials recruited him to survey much of the city, and soon he became known as Omaha’s authority on land transfers. A few short years later the city would boom upon, not the increasing growth of river trade, but instead the back of Lincoln’s 1862 Pacific Railway Act. The proclamation placed Omaha as the central hub of this new ribbon of steel, and with the rail line’s construction in 1863 (J. Brown, 2012), it solidified the city as, “the gateway city to the west.” Soon after, Omaha became the heart from which these wealth conveying railroads flowed. With the completion of these early railroad lines, including the Union Pacific, Burlington and Quincy, and the Chicago-Rock Island and Pacific, subsequent immigration quickly amplified, spurred by news of early pioneers’ successes and cheap government subsidized land (X. Duran, 2013). Consequently, urbanization trailed closely in its wake, abetting the rampant commodification of the western frontier and the rise of real estate industry.

Fighting for a premium position upon the 19th century world stage, the United States engaged in increasingly expansive trade policies and practices in order to compete with strengthening global competition (A. Menard, 2011). The Pacific Railway Act of 1862, a component of this political platform, was seen as an essential element to the United States success, with its railroads serving as the cornerstone linkages in expanding American trade (W. Webb, 1931 and X. Duran, 2013) . However, the rail lines quickly became more than a means to traverse the vast expanses of the Midwest. Previously unexploited, the tall grass prairies of the American western front, overflowing with rich natural resources, epitomized cheap nature worthy of great exploitation. Access though, had long been problematic, limiting the tremendous potential for capital accumulation (R. Billington, 1974). The expansion of these nineteenth century railroads, however, essentially resolved the access problems, simultaneously pulling the American economy and millions of settlers westward into a new frontier. Consequently, the resources necessary to extract the riches of prairie ecosystems were suddenly at the very fingertips of the early migrating farmers, igniting an agricultural boom. The once virgin Midwestern soils were busted, fertilized, cultivated, and commodified, with exceptional wealth materializing at the expense of nature. Skyrocketing land values in the late 19th century Midwest exemplify this sudden explosion of capital potential, with railroad centered lands of the Nebraska and Kansas territories exhibiting average price increases of $3.10 per acre upon railroad completion, representing a 24% rise in value (C. S. Decker and D. T. Flynn, 2007).

As a result of these changes, Omaha’s industry and population exploded, and Reed, who had amassed a good deal of land around and outside the city prior to the railroads’ arrival (Figure 4), quickly became a wealthy man. Whether selling urban property, or rural agriculture, the once virgin and untouched land which Reed dealt became fundamentally altered and commodified in the wake of the new frontiers arrival. Simultaneously, Reed became an actor and benefactor of the capitally driven western commodity frontier. Not unlike the many other 1850’s and 1860’s American western migrants who saw their fortunes soar with the development of the western frontier (J. Stewart, 2006), Reed was soon worth over an estimated two million dollars. Buoyed by his sudden wealth, he continued to collect land throughout his life, affirmed by the large number of city plots, the additions, and more than 350 acres of farmland he possessed at the time of his death (M. Brown, 1989 and Omaha Sunday World-Herald, June 7, 1891). However, his collection interests expanded beyond land alone. Fascinated by coins, Reed accumulated one of the finest coin collections in the world, in the middle of which sat the Spanish silver Reales, the very piece of history responsible for producing the capitalistic, commodifying, anthropogenic age that made Reed’s collection possible.

While time has muddied the waters between Byron Reed’s Spanish silver and the new human epoch, the Anthropocene, exploring the era’s roots in capitalism and the commodity system crystallizes the distorted relationships. An exemplary western front migrant, Reed built both his reputation and his fortune off this new 19th century commodity frontier. However, while railroads and agriculture, rather than imperialistic lust and mining, characterized the front, its ties to Potosi silver, remain indisputable. Appropriated in the 16th century, Spanish mining of Cerro Rico, the silver mountain, simultaneously became the model, and the agent of change in ushering in a new economic era. Upon this mountain’s rich and mighty slopes, a mindset of production orientation was born, spreading the Spanish silver Reales and paving the way for globalization and intensive nature commodification. Thus, despite their superficial differences, the American western frontier, which delivered Bryon Reed his fortune and his Spanish Reales, fundamentally mirrored its silver 16th century counterpart, both being driven by an insatiable appetite for capital accumulation at the expense of commodified nature.

Creator

Ian Reuter

Dakota Wagner

Dakota Wagner

Source

Blaut, James M. On the Significance of 1492. Political Geography, 11, no. 4 (1992): 355-385. doi: 10.1016/0962-6298(92)90003-C.

Blaut, James M. Where was Capitalism Born? Antipode, 8 no. 2 (1976): 1-11. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8330.1976.tb00633.x

Moore, Jason W. "‘Amsterdam is Standing on Norway’ Part I: The Alchemy of Capital, Empire and Nature in the Diaspora of Silver, 1545–1648." Journal Of Agrarian Change 10, no. 1 (2010): 33-68. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed November 4, 2017).

Moore, Jason. “Silver, Ecology, and the Origins of the Modern World, 1450-1640.” In Rethinking Environmental History: World-System History and Global Environmental Change, edited by Hornborg, Alf, J. R. McNeill, and Juan Martínez-Alier 123-142. Plymouth: AltaMira Press: 2007.

Moore, Jason W. “’This lofty mountain of silver could conquer the whole world.’ Potosi and the political ecology of underdevelopment, 1545-1800.” Journal of Philosophical Economics, 4 no. 1 (2010): 58-103. https://jpe.ro/?id=b1&cuprins=ascuns.

a. “In the first two decades after Spain’s enclosure of Potosí, the ores were rich indeed. Soon, however, ore quality declined sharply. By the late 1560’s, the yield on Potosí ore fell 98 percent from two decades earlier.”

b. “Declining yield implied rising fuel inputs, the major production cost for smelter.” Ore refinement consequently became a major sink of fuel and labor, exacerbated by the “transition to mercury amalgamation… because it reduced per unit fuel costs…it enabled such a large increase in output over so short a time, the consequence was more, not less deforestation”

c. “Construction and fuel needs devoured the forests around Potosí, driving successive expansions of the timber hinterland. By 1714, Potosí, was drawing timber from Paraguay”

Barragán, Rossana. "Working Silver for the World: Mining Labor and Popular Economy in Colonial Potosí." Hispanic American Historical Review 97, no. 2 (2017): 193-222. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed November 5, 2017).

a. “Until Spanish 1575 reforms in labor, indigenous population carried out the extraction at their own cost and largely for their own benefit… in contrast the forced labor system ‘mita’ established afterwards, lacked the principle of protections found in slavery systems, instead the Potosí system had no safeguards against overexploitation”

Galeano, Eduardo. Open veins of Latin America: five centuries of the pillage of a continent. Carlton North, Vic.: Scribe Publications, 1973.

Moore, Jason W. “The Capitalocene, Part I: On the Nature and Origins of our Ecological Crisis.” The Journal of Peasant Studies, 44 no. 4, 2017: 594-630. http://www.tandfonline.com/.

a. Moore identifies four forms of “cheap nature” implicit in the rise of expansive capitalistic commodification which he defines as “labor-power, food, energy, and raw materials.”

O. Flynn, Dennis, and Arturo Giraldez. Born with a “Silver Spoon”: The Origin of World Trade in 1571. Journal of World History, 6 no. 2 (1995): 201-222. http://www.uhpress.hawaii.edu/journals.aspx.

Jorgenson, Andrew K., and Edward L. Kick L. “Introduction: Globalization and the Environment.” Journal of World-Systems Research, 9 no. 2 (2003): 195-203. https://doi.org/10.5195/jwsr.2003.243.

O. Flynn, Dennis, and Arturo Giraldez. "Cycles of Silver: Global Economic Unity through the Mid-Eighteenth Century*." Journal Of World History 13, no. 2 (2002): 391. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed November 5, 2017).

a. “In the early 16th century the gold/silver ratio in China stood at 1:6, while in contrast the gold/silver ratio hovered around 1:12 in Europe.”

b. “Within two years of Spain’s 1865 establishment of a port in the Philippines, which linked Chinese demand for silver directly to its major producer, China ended its prohibition on overseas trade.”

Schell Jr., William. "Silver Symbiosis: ReOrienting Mexican Economic History." Hispanic American Historical Review 81, no. 1 (2001): 89. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed November 5, 2017).

Moore, Jason W. "‘Amsterdam is Standing on Norway’ Part II: The Global North Atlantic in the Ecological Revolution of the Long Seventeenth Century." Journal Of Agrarian Change 10, no. 2 (2010): 188-227. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed November 4, 2017).

Menard, Andrew. "Striking a Line through the Great American Desert." Journal Of American Studies 45, no. 2 (2011): 267-280. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed November 4, 2017).

Webb, Walter P. The Great Plain. London: Penguin Publishing Group, 1931.

Duran, Xavier. "The First U.S. Transcontinental Railroad: Expected Profits and Government Intervention." Journal Of Economic History 73, no. 1 (2013): 177-200. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed November 4, 2017).

Billington, Ray A. Westward Expansion: A History of the American Frontier., 4th edition: New York: MacMillan Publishing Co., 1974.

Decker, Christopher S., and David T. Flynn. "The Railroad's Impact on Land Values in the Upper Great Plains at the Closing of the Frontier." Historical Methods 40, no. 1 (2007): 28-38. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed November 4, 2017).

Brown, Jeff. "Uniting the States: The First Transcontinental Railroad." Civil Engineering (08857024) 82, no. 7/8 (2012): 40-42. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed November 4, 2017).

a. Signed into law by Abraham Lincoln on July 1, 1862, the Pacific Railroad Act launched the construction of a 1,776 mile long railroad from the Missouri River to the Pacific Ocean. Work began on the eastern side of the railroad in Omaha, Nebraska in December 1863. Six years later, on May 10, 1869, at Promontory Summit, Utah, the final spike was driven into the railroad marking the completion of the first transcontinental railroad.

Western Heritage Museum. Byron Reed Exhibit Pamphlet. Omaha: 1985.

“Byron Reed Passes Away.” Omaha Sunday World-Herald (Omaha), June 7, 1891, 5.

a. Identified as an informant for a Union newspaper while behind Confederate lines in Kansas, Reed was lucky to evade capture, which could have come with dire consequences.

Bryon Reed Company, Inc. The Story of Omaha. Omaha: 1956.

Stewart, James I. "Migration to the Agricultural Frontier and Wealth Accumulation, 1860–1870." Explorations In Economic History 43, no. 4 (2006): 547-577. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed November 4, 2017).

a. “Frontier migrants accumulated wealth at rates that were high and in excess of those in non-frontier areas…. increasing their wealth eightfold over the decade or twice as much as those who did not migrate.”

Brown, Marion M. “Byron Reed the Man Behind the Treasure.” Sunday World-Herald Magazine of the Midlands. (Omaha), April 2, 1989.

Arce-Burgoa, Osvaldo R. and Richard J. Goldfarb. “Metallogeny of Bolivia.” Society of Economic Geologists Newsletter, No. 79 (2009).http://www.dim.uchile.cl/~lsaavedr/archivos/joseline/pdf/Metallogeny%20of%20Bolivia.pdf

a. “The Cerro Rico de Potosi polymetallic vein deposit, mined since the mid-1500s, is the world’s largest silver deposit. It has yielded 60,000 tons of silver making Bolivia the largest silver producer in the world for more than two centuries.”

Shahriari, Sara. “Bolivia: Struggling to save the mountain that eats men.” Aljazeera America. May 8th, 2014. http://america.aljazeera.com/articles/2014/5/8/struggling-to-savethemountainthateatsmen.html.

“Spain Spanish Colonial Reales.” Coin Quest. Accessed November 6th, 2017. http://coinquest.com/cgi-bin/cq/coins?main_coin=2334.

“Maps.” Omaha Landmarks Heritage Preservation Commission. Accessed November 6th, 2017. https://landmark.cityofomaha.org/maps.

Blaut, James M. Where was Capitalism Born? Antipode, 8 no. 2 (1976): 1-11. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8330.1976.tb00633.x

Moore, Jason W. "‘Amsterdam is Standing on Norway’ Part I: The Alchemy of Capital, Empire and Nature in the Diaspora of Silver, 1545–1648." Journal Of Agrarian Change 10, no. 1 (2010): 33-68. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed November 4, 2017).

Moore, Jason. “Silver, Ecology, and the Origins of the Modern World, 1450-1640.” In Rethinking Environmental History: World-System History and Global Environmental Change, edited by Hornborg, Alf, J. R. McNeill, and Juan Martínez-Alier 123-142. Plymouth: AltaMira Press: 2007.

Moore, Jason W. “’This lofty mountain of silver could conquer the whole world.’ Potosi and the political ecology of underdevelopment, 1545-1800.” Journal of Philosophical Economics, 4 no. 1 (2010): 58-103. https://jpe.ro/?id=b1&cuprins=ascuns.

a. “In the first two decades after Spain’s enclosure of Potosí, the ores were rich indeed. Soon, however, ore quality declined sharply. By the late 1560’s, the yield on Potosí ore fell 98 percent from two decades earlier.”

b. “Declining yield implied rising fuel inputs, the major production cost for smelter.” Ore refinement consequently became a major sink of fuel and labor, exacerbated by the “transition to mercury amalgamation… because it reduced per unit fuel costs…it enabled such a large increase in output over so short a time, the consequence was more, not less deforestation”

c. “Construction and fuel needs devoured the forests around Potosí, driving successive expansions of the timber hinterland. By 1714, Potosí, was drawing timber from Paraguay”

Barragán, Rossana. "Working Silver for the World: Mining Labor and Popular Economy in Colonial Potosí." Hispanic American Historical Review 97, no. 2 (2017): 193-222. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed November 5, 2017).

a. “Until Spanish 1575 reforms in labor, indigenous population carried out the extraction at their own cost and largely for their own benefit… in contrast the forced labor system ‘mita’ established afterwards, lacked the principle of protections found in slavery systems, instead the Potosí system had no safeguards against overexploitation”

Galeano, Eduardo. Open veins of Latin America: five centuries of the pillage of a continent. Carlton North, Vic.: Scribe Publications, 1973.

Moore, Jason W. “The Capitalocene, Part I: On the Nature and Origins of our Ecological Crisis.” The Journal of Peasant Studies, 44 no. 4, 2017: 594-630. http://www.tandfonline.com/.

a. Moore identifies four forms of “cheap nature” implicit in the rise of expansive capitalistic commodification which he defines as “labor-power, food, energy, and raw materials.”

O. Flynn, Dennis, and Arturo Giraldez. Born with a “Silver Spoon”: The Origin of World Trade in 1571. Journal of World History, 6 no. 2 (1995): 201-222. http://www.uhpress.hawaii.edu/journals.aspx.

Jorgenson, Andrew K., and Edward L. Kick L. “Introduction: Globalization and the Environment.” Journal of World-Systems Research, 9 no. 2 (2003): 195-203. https://doi.org/10.5195/jwsr.2003.243.

O. Flynn, Dennis, and Arturo Giraldez. "Cycles of Silver: Global Economic Unity through the Mid-Eighteenth Century*." Journal Of World History 13, no. 2 (2002): 391. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed November 5, 2017).

a. “In the early 16th century the gold/silver ratio in China stood at 1:6, while in contrast the gold/silver ratio hovered around 1:12 in Europe.”

b. “Within two years of Spain’s 1865 establishment of a port in the Philippines, which linked Chinese demand for silver directly to its major producer, China ended its prohibition on overseas trade.”

Schell Jr., William. "Silver Symbiosis: ReOrienting Mexican Economic History." Hispanic American Historical Review 81, no. 1 (2001): 89. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed November 5, 2017).

Moore, Jason W. "‘Amsterdam is Standing on Norway’ Part II: The Global North Atlantic in the Ecological Revolution of the Long Seventeenth Century." Journal Of Agrarian Change 10, no. 2 (2010): 188-227. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed November 4, 2017).

Menard, Andrew. "Striking a Line through the Great American Desert." Journal Of American Studies 45, no. 2 (2011): 267-280. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed November 4, 2017).

Webb, Walter P. The Great Plain. London: Penguin Publishing Group, 1931.

Duran, Xavier. "The First U.S. Transcontinental Railroad: Expected Profits and Government Intervention." Journal Of Economic History 73, no. 1 (2013): 177-200. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed November 4, 2017).

Billington, Ray A. Westward Expansion: A History of the American Frontier., 4th edition: New York: MacMillan Publishing Co., 1974.

Decker, Christopher S., and David T. Flynn. "The Railroad's Impact on Land Values in the Upper Great Plains at the Closing of the Frontier." Historical Methods 40, no. 1 (2007): 28-38. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed November 4, 2017).

Brown, Jeff. "Uniting the States: The First Transcontinental Railroad." Civil Engineering (08857024) 82, no. 7/8 (2012): 40-42. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed November 4, 2017).

a. Signed into law by Abraham Lincoln on July 1, 1862, the Pacific Railroad Act launched the construction of a 1,776 mile long railroad from the Missouri River to the Pacific Ocean. Work began on the eastern side of the railroad in Omaha, Nebraska in December 1863. Six years later, on May 10, 1869, at Promontory Summit, Utah, the final spike was driven into the railroad marking the completion of the first transcontinental railroad.

Western Heritage Museum. Byron Reed Exhibit Pamphlet. Omaha: 1985.

“Byron Reed Passes Away.” Omaha Sunday World-Herald (Omaha), June 7, 1891, 5.

a. Identified as an informant for a Union newspaper while behind Confederate lines in Kansas, Reed was lucky to evade capture, which could have come with dire consequences.

Bryon Reed Company, Inc. The Story of Omaha. Omaha: 1956.

Stewart, James I. "Migration to the Agricultural Frontier and Wealth Accumulation, 1860–1870." Explorations In Economic History 43, no. 4 (2006): 547-577. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed November 4, 2017).

a. “Frontier migrants accumulated wealth at rates that were high and in excess of those in non-frontier areas…. increasing their wealth eightfold over the decade or twice as much as those who did not migrate.”

Brown, Marion M. “Byron Reed the Man Behind the Treasure.” Sunday World-Herald Magazine of the Midlands. (Omaha), April 2, 1989.

Arce-Burgoa, Osvaldo R. and Richard J. Goldfarb. “Metallogeny of Bolivia.” Society of Economic Geologists Newsletter, No. 79 (2009).http://www.dim.uchile.cl/~lsaavedr/archivos/joseline/pdf/Metallogeny%20of%20Bolivia.pdf

a. “The Cerro Rico de Potosi polymetallic vein deposit, mined since the mid-1500s, is the world’s largest silver deposit. It has yielded 60,000 tons of silver making Bolivia the largest silver producer in the world for more than two centuries.”

Shahriari, Sara. “Bolivia: Struggling to save the mountain that eats men.” Aljazeera America. May 8th, 2014. http://america.aljazeera.com/articles/2014/5/8/struggling-to-savethemountainthateatsmen.html.

“Spain Spanish Colonial Reales.” Coin Quest. Accessed November 6th, 2017. http://coinquest.com/cgi-bin/cq/coins?main_coin=2334.

“Maps.” Omaha Landmarks Heritage Preservation Commission. Accessed November 6th, 2017. https://landmark.cityofomaha.org/maps.

Relation

Collection

Citation

Ian Reuter

Dakota Wagner, “Spanish Silver Reales,” Omaha in the Anthropocene, accessed May 6, 2024, https://steppingintothemap.com/anthropocene/items/show/13.

Embed

Copy the code below into your web page