Single-Wheel Hoe

Title

Single-Wheel Hoe

Subject

Humans spent thousands of years hunting and gathering before the development of agriculture. Scientists call this change the “Neolithic Revolution.” Many argue this was the start of the Anthropocene. Plows and hoes have been a part of this story for over 4000 years. The “single wheel hoe” on display was handmade and likely built during the twentieth century. It overturns soil, buries weeds, and mixes nutrients. Nebraska’s agriculture grew as it industrialized in the nineteenth century. Farmers looked to companies in Omaha to supply necessary tools. Agriculture became the state’s basic source of wealth, and Omaha grew alongside it. As industrial agriculture grew globally in the 20th century, environmental consequences came with it, such as during the Dust Bowl in the 1930s or the USSR in the 1940s. The single wheel hoe predates this global shift towards agriculture. This hoe reminds us that agriculture takes many forms.

Description

Reliable food sources have been a major aspect of human life since the dawn of our existence. Humans spent thousands of years hunting and gathering until a new way of life emerged; the settled lifestyle of the agriculturalist. As agriculture became a widespread practice and the populations grew, human societies needed to find new ways to cultivate the land faster and more efficiently. Plows became increasingly popular as one of the main tools used to aid in the expansion of farming. Many farmers used plows to overturn the soil leaving the fertile earth on top, bury weeds, and mix soil. Small, hand held plows developed into to horse and oxen-drawn plows, which, by the nineteenth century progressed to larger industrial plows. Plowing has left an indelible impression on global landscapes and the Nebraskan environment. In the nineteenth century, “sod-busting” became synonymous with the idealized, American frontier ethic. It represented the pioneering spirit, the “progress” of westward expansion, and improvement and mastery of nature.

More recent historians have viewed sod-busting with a more critical gaze. Geoff Cunfer has gone so far as to call plowing “ecocide” due to the disastrous effects humans and the implements we use have had on the ecosystem. (Cunfer, 2005) Our object reminds us that agriculture need not be synonymous with environmental “destruction.” The plow did not inevitably “break the plains.” However, many farmers throughout the nineteenth century and still today use a variety of agricultural implements, many of which confute these characterizations. Smaller, handheld plows, for instance, used in “backyard” farms promote healthier agricultural practices. These rudimentary plows are some of the least environmentally invasive yet beneficial instruments used in farming history. The plow is an important artifact in Omaha’s environmental history due to its contribution to the agricultural foundation on which Omaha and the greater Nebraska area was built. It links Omaha’s environmental history to the global history of the Anthropocene through the worldwide shift towards farming which has changed many aspects of the world we live in.

The story of the plow begins after the Neolithic revolution. Early plow prototypes first appeared nearly 4,000 years ago in Sumar and Egypt in a dry environment that required moisture in the soil. (Pryor, 1985) These plows had rudimentary structures that would be barely recognizable if compared to the plows of present day. Many advancements took place over the years including the addition of wheels and improved handles to make maneuvering the plow through the fields easier. By the nineteenth century, farmers relied on local blacksmiths to produce the necessary farm tools. (Bonney, 1981) The plows produced during this time were made with metal bolts and bars, which attached the wood handles to the cultivators and wheels. In order to make a better furrow, blacksmiths incorporated cast iron parts into the plow design during the late 19th century to decrease the amount of soil that stuck to the plow. Prior to this development, plowing with an animal such as oxen required three farmers. The first to drive the plow, another to steer, and the last to clean the dirt off the blade. John Deere provided an even greater advancement of the plow through his creation of a steel plow. With Deere’s new steel design, the soil did not stick to the hoe and it pulled with less resistance. This decreased the amount of time, labor, and number of farmers needed to plow. Even with sharper pieces on the plows to cut through the soil easier, “a farmer walking behind a plow could only plow two acres a day.” (Bonney, 1981) By the end of the 19th century, machines pulled by horses were used instead of the human driven implements and farmers could plow up to seven acres a day.

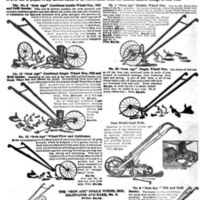

In 1903 there were different types of single wheel hoes and attachments available. These advertisements were used to display the prices varying from $3.75 to $11.00. With low prices like these, hoes were not limited to mass-production farmers, they could be used in the backyard. By 1911, the single wheeled hoe with one plows, multiple wheels, two hoes, three cultivator teeth, and rakes attached was selling for as little as $5.35 (Iron Age Farm and Garden Tools of 1903) (Figure 1).

The single wheeled hoe is a type of plow, but one with a fundamentally different purpose. Rather than producing food to be sold in quantity, it would have been used for gardening. Plains farmers, even those with significant acreage planted in single crops, often cultivated large kitchen gardens. Farmers growing vegetables typically use wheel cultivators to aid in their gardening (Figure 2). These smaller plows are used to “loosen the soil, allow moisture to reach the roots of crops and to keep down the weeds." (Moulton, 1997) A single wheeled hoe is useful because farmers are able to plant seeds in more narrow rows compared to the rows created by using a double wheeled plow or a plow pulled by a horse. This allows more crops to be produced in a smaller space thereby increasing productivity.

The tire used in this plow resembles that of a bicycle tire contributing to our argument that this was a homemade implement. The wooden arms of the plow appear to be screwed to the cultivator teeth. This single-wheeled hoe is made of a bike tire, two wooden handles, and steel cultivator teeth. The object is useful for both amateur and professional gardeners. Recreational gardeners use it to save time and decrease effort. Professional gardeners use this object because it is more precise. It is also sturdier and can be effective though “many sessions… The hoes are used for weeding, mulching, and shallow cultivation… The cultivator teeth or ‘duckfeet’ are for general cultivation. They have a narrow neck with a wide head for turning over the weeds. The plow is rugged enough to do real plowing or furrowing.” (History of the Wheel Hoe)

This object is in The Durham Museum's collection because of the many agricultural supplies produced in Omaha as well as the numerous farms in the surrounding area. One place of this production in Omaha was the Parlin Orendorff and Martin Plow Co. This building of this wholesale company was located at 707 S 11th Street in Omaha and was built in 1906 (Figure 3). The railroad and nearby river were used to distribute the agricultural tools from this building. In 1903 the main interests in South Omaha included livestock and packing. At that time, Omaha “[had] some good agricultural lands outlying." (Wills, 1995) While it is believed that this object was handmade, it may have been inspired by products made in this building.

In the territorial period, farming was limited in Nebraska. Farms were only about fifty acres, and the “tools and implements” were crude and simple. Markets for agricultural products were few, and capital for investment was in short supply. But after Nebraska was linked by rail to the East by 1869, farming was transformed into the state’s basic producer of wealth - the foundation of its economy.” (Traveler's Railway Guide, 1903) Plows became more common by the 1870s. “Nebraska farmers could buy a variety of new and improved plows… [and] cultivators." (Luebke, 2005) The plows used during this time allowed farmers to produce large quantities of crops that stimulated economic growth and the personal wealth of these farmers. Due to this economic impact, the cities of Nebraska were able to develop homes and businesses that lead to the establishment of cities like Omaha”. This single wheeled hoe was used in both amateur and professional gardener: recreationally or occupationally.

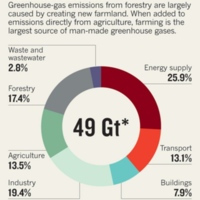

The Anthropocene highlights a history of human impact on the environment that is commonly seen in a negative light. Plows can easily be added to the list of man-made implements that produce disastrous environmental changes and threaten the future of the earth. Major events such as the Dust Bowl have been attributed to the overuse of plows and show the disastrous effects the plow can have on the environment. (Plow that Broke the Plains, 1936) Areas of land that are continuously plowed can quickly become useless for farming due to soil erosion and nutrient depletion from the earth that continues long after the land is abandoned. (Ciampalini et al, 2012) As the soil erodes it is carried away by water runoff or wind and becomes pollution in the air and water. Some soil and nutrients end up in nearby ponds or lakes making them dirty and reducing photosynthesis. (Lal, Reicosky, and Hanson, 2007) The pH of the soil is also affected by long-term plowing as well as the hydration of the soil which affects the soil’s ability to sustain crops over time. (Hester and Marrison, 2012; Percy, 1992) In addition to these more tangible effects, other consequences of plowing affect the earth’s atmosphere (Figure 4). Carbon dioxide and nitrogen emissions play a major role in the environmental change. As these harmful substances are released from the soil, they go into the atmosphere where they contribute to holes in the ozone and global warming. As shown in the following chart, plowing and other farming practices have had a major impact on environmental change. (Gilbert, 2011)

However, single wheeled plows such as this one must be viewed from a different perspective. These smaller plows are used to participate in small scale, oftentimes organic farming that produces far fewer emissions and soil disruption than the large-scale plows. (Wu and Xie, 2011) They oftentimes do not use pesticides which helps decrease the runoff of toxins into the surrounding water and air. Smaller farms also commonly practice crop rotation which fosters healthier soil that does not require nearly as many fertilizers to grow healthy crops. The use of smaller plows such as this single wheeled hoe helps increase carbon storage and decreases nutrient depletion. (Bengtsson, Ahnstrohm, and Weibull, 2005) While the scale of these positive environmental impacts of farming with a single wheeled hoe are varied based on location and climate of the region, it is clear that this local farming avoids many of the harmful impacts of commercial farming. Additionally, urban farming does not require the removal of natural environments such as forests that oftentimes accompanies larger rural farming.

This object is connected to the Anthropocene by the themes of agriculture, industrialization, and the growth of industry. The plow is deeply rooted in the history of agriculture, as it has remained a major contributor to the success of farming. The plow has been used in many cultures across the world for thousands of years. Preceded by the use of a digging stick, plows have changed the scale on which humans interact with the land. The plow’s association with agriculture assisted in creating an environmental impact that included the selection of species, indirect influences, ecosystem change, population pressure, climate change, and farming pressure. The environmental impact of the plow accelerated during the nineteenth century as a result of industrialization and the expansion of resource frontiers . via railroads, linking increasingly distant farmlands to growing cities. The farming implements themselves were also transported on these rail networks after the Industrial Revolution. As time went on, according to historian Michael Kopsidis, “demand from cities generated incentives for an intensification of agriculture. In this view, the urban dwellers that specialized in commerce, crafts, proto-industry, trade, and later on industry, were important and concentrated sources of demand for the output of farms.” (Kopsidis and Wolf, 2012) Companies were created for the sole purpose of selling this groundbreaking equipment to farmers. One of the most famous farm equipment companies, the John Deere Corporation, was founded due to their creation of a self-scouring steel plow. In addition to their popularity in the retail market, the plow’s capacity to strip soil of its nutrients has resulted in the need to quickly replace the lost nutrients of the soil. (Gregg, 2015)

The plow has played a significant role in the history of agriculture as well as the emergence of the Anthropocene. Through its utility the plow has become one of the most influential instruments used in the farming community today. From the time people first began using plows, their usage had progressively increased. Farmers now rely heavily on plows to efficiently increase their crop production by burying weeds and previously planted crops and increased soil fertility. While historically most plows looked similar to this one, the farming equipment industry has exploded and today most plows are massive machines pulled by tractors used to cultivate hundreds of acres of farmland. The advancement of plows, although more efficient, have unfavorable impacts on the environment. However, plows similar to this single wheeled hoe have had a more positive effect on the environment through their promotion of organic farming methods that reduce the amount of toxins released into their environments. Our single wheeled hoe, thus, reflects a more hopeful view of the Anthropocene. Lately the focus has shifted to finding ways to use the plow responsibly to reduce its negative impacts. Recognizing the capacity of the land and shifting to the use of smaller plows such as this one could help reduce the emissions produced by large-scale farming. Farmers could also plant trees and shrubs surrounding their farms to reduce the wind erosion that is supported by the plowing 18 . These steps must be taken to reduce the impacts of the plow on the earth that can be seen through the Anthropocene. The plow has played a major role in the environmental history of Omaha through its contribution to the agriculture both within Omaha and the surrounding area. The effects of the plow must be considered with looking at the global history of the Anthropocene as it directly relates to the widespread shift towards farming which has greatly influenced our world.

More recent historians have viewed sod-busting with a more critical gaze. Geoff Cunfer has gone so far as to call plowing “ecocide” due to the disastrous effects humans and the implements we use have had on the ecosystem. (Cunfer, 2005) Our object reminds us that agriculture need not be synonymous with environmental “destruction.” The plow did not inevitably “break the plains.” However, many farmers throughout the nineteenth century and still today use a variety of agricultural implements, many of which confute these characterizations. Smaller, handheld plows, for instance, used in “backyard” farms promote healthier agricultural practices. These rudimentary plows are some of the least environmentally invasive yet beneficial instruments used in farming history. The plow is an important artifact in Omaha’s environmental history due to its contribution to the agricultural foundation on which Omaha and the greater Nebraska area was built. It links Omaha’s environmental history to the global history of the Anthropocene through the worldwide shift towards farming which has changed many aspects of the world we live in.

The story of the plow begins after the Neolithic revolution. Early plow prototypes first appeared nearly 4,000 years ago in Sumar and Egypt in a dry environment that required moisture in the soil. (Pryor, 1985) These plows had rudimentary structures that would be barely recognizable if compared to the plows of present day. Many advancements took place over the years including the addition of wheels and improved handles to make maneuvering the plow through the fields easier. By the nineteenth century, farmers relied on local blacksmiths to produce the necessary farm tools. (Bonney, 1981) The plows produced during this time were made with metal bolts and bars, which attached the wood handles to the cultivators and wheels. In order to make a better furrow, blacksmiths incorporated cast iron parts into the plow design during the late 19th century to decrease the amount of soil that stuck to the plow. Prior to this development, plowing with an animal such as oxen required three farmers. The first to drive the plow, another to steer, and the last to clean the dirt off the blade. John Deere provided an even greater advancement of the plow through his creation of a steel plow. With Deere’s new steel design, the soil did not stick to the hoe and it pulled with less resistance. This decreased the amount of time, labor, and number of farmers needed to plow. Even with sharper pieces on the plows to cut through the soil easier, “a farmer walking behind a plow could only plow two acres a day.” (Bonney, 1981) By the end of the 19th century, machines pulled by horses were used instead of the human driven implements and farmers could plow up to seven acres a day.

In 1903 there were different types of single wheel hoes and attachments available. These advertisements were used to display the prices varying from $3.75 to $11.00. With low prices like these, hoes were not limited to mass-production farmers, they could be used in the backyard. By 1911, the single wheeled hoe with one plows, multiple wheels, two hoes, three cultivator teeth, and rakes attached was selling for as little as $5.35 (Iron Age Farm and Garden Tools of 1903) (Figure 1).

The single wheeled hoe is a type of plow, but one with a fundamentally different purpose. Rather than producing food to be sold in quantity, it would have been used for gardening. Plains farmers, even those with significant acreage planted in single crops, often cultivated large kitchen gardens. Farmers growing vegetables typically use wheel cultivators to aid in their gardening (Figure 2). These smaller plows are used to “loosen the soil, allow moisture to reach the roots of crops and to keep down the weeds." (Moulton, 1997) A single wheeled hoe is useful because farmers are able to plant seeds in more narrow rows compared to the rows created by using a double wheeled plow or a plow pulled by a horse. This allows more crops to be produced in a smaller space thereby increasing productivity.

The tire used in this plow resembles that of a bicycle tire contributing to our argument that this was a homemade implement. The wooden arms of the plow appear to be screwed to the cultivator teeth. This single-wheeled hoe is made of a bike tire, two wooden handles, and steel cultivator teeth. The object is useful for both amateur and professional gardeners. Recreational gardeners use it to save time and decrease effort. Professional gardeners use this object because it is more precise. It is also sturdier and can be effective though “many sessions… The hoes are used for weeding, mulching, and shallow cultivation… The cultivator teeth or ‘duckfeet’ are for general cultivation. They have a narrow neck with a wide head for turning over the weeds. The plow is rugged enough to do real plowing or furrowing.” (History of the Wheel Hoe)

This object is in The Durham Museum's collection because of the many agricultural supplies produced in Omaha as well as the numerous farms in the surrounding area. One place of this production in Omaha was the Parlin Orendorff and Martin Plow Co. This building of this wholesale company was located at 707 S 11th Street in Omaha and was built in 1906 (Figure 3). The railroad and nearby river were used to distribute the agricultural tools from this building. In 1903 the main interests in South Omaha included livestock and packing. At that time, Omaha “[had] some good agricultural lands outlying." (Wills, 1995) While it is believed that this object was handmade, it may have been inspired by products made in this building.

In the territorial period, farming was limited in Nebraska. Farms were only about fifty acres, and the “tools and implements” were crude and simple. Markets for agricultural products were few, and capital for investment was in short supply. But after Nebraska was linked by rail to the East by 1869, farming was transformed into the state’s basic producer of wealth - the foundation of its economy.” (Traveler's Railway Guide, 1903) Plows became more common by the 1870s. “Nebraska farmers could buy a variety of new and improved plows… [and] cultivators." (Luebke, 2005) The plows used during this time allowed farmers to produce large quantities of crops that stimulated economic growth and the personal wealth of these farmers. Due to this economic impact, the cities of Nebraska were able to develop homes and businesses that lead to the establishment of cities like Omaha”. This single wheeled hoe was used in both amateur and professional gardener: recreationally or occupationally.

The Anthropocene highlights a history of human impact on the environment that is commonly seen in a negative light. Plows can easily be added to the list of man-made implements that produce disastrous environmental changes and threaten the future of the earth. Major events such as the Dust Bowl have been attributed to the overuse of plows and show the disastrous effects the plow can have on the environment. (Plow that Broke the Plains, 1936) Areas of land that are continuously plowed can quickly become useless for farming due to soil erosion and nutrient depletion from the earth that continues long after the land is abandoned. (Ciampalini et al, 2012) As the soil erodes it is carried away by water runoff or wind and becomes pollution in the air and water. Some soil and nutrients end up in nearby ponds or lakes making them dirty and reducing photosynthesis. (Lal, Reicosky, and Hanson, 2007) The pH of the soil is also affected by long-term plowing as well as the hydration of the soil which affects the soil’s ability to sustain crops over time. (Hester and Marrison, 2012; Percy, 1992) In addition to these more tangible effects, other consequences of plowing affect the earth’s atmosphere (Figure 4). Carbon dioxide and nitrogen emissions play a major role in the environmental change. As these harmful substances are released from the soil, they go into the atmosphere where they contribute to holes in the ozone and global warming. As shown in the following chart, plowing and other farming practices have had a major impact on environmental change. (Gilbert, 2011)

However, single wheeled plows such as this one must be viewed from a different perspective. These smaller plows are used to participate in small scale, oftentimes organic farming that produces far fewer emissions and soil disruption than the large-scale plows. (Wu and Xie, 2011) They oftentimes do not use pesticides which helps decrease the runoff of toxins into the surrounding water and air. Smaller farms also commonly practice crop rotation which fosters healthier soil that does not require nearly as many fertilizers to grow healthy crops. The use of smaller plows such as this single wheeled hoe helps increase carbon storage and decreases nutrient depletion. (Bengtsson, Ahnstrohm, and Weibull, 2005) While the scale of these positive environmental impacts of farming with a single wheeled hoe are varied based on location and climate of the region, it is clear that this local farming avoids many of the harmful impacts of commercial farming. Additionally, urban farming does not require the removal of natural environments such as forests that oftentimes accompanies larger rural farming.

This object is connected to the Anthropocene by the themes of agriculture, industrialization, and the growth of industry. The plow is deeply rooted in the history of agriculture, as it has remained a major contributor to the success of farming. The plow has been used in many cultures across the world for thousands of years. Preceded by the use of a digging stick, plows have changed the scale on which humans interact with the land. The plow’s association with agriculture assisted in creating an environmental impact that included the selection of species, indirect influences, ecosystem change, population pressure, climate change, and farming pressure. The environmental impact of the plow accelerated during the nineteenth century as a result of industrialization and the expansion of resource frontiers . via railroads, linking increasingly distant farmlands to growing cities. The farming implements themselves were also transported on these rail networks after the Industrial Revolution. As time went on, according to historian Michael Kopsidis, “demand from cities generated incentives for an intensification of agriculture. In this view, the urban dwellers that specialized in commerce, crafts, proto-industry, trade, and later on industry, were important and concentrated sources of demand for the output of farms.” (Kopsidis and Wolf, 2012) Companies were created for the sole purpose of selling this groundbreaking equipment to farmers. One of the most famous farm equipment companies, the John Deere Corporation, was founded due to their creation of a self-scouring steel plow. In addition to their popularity in the retail market, the plow’s capacity to strip soil of its nutrients has resulted in the need to quickly replace the lost nutrients of the soil. (Gregg, 2015)

The plow has played a significant role in the history of agriculture as well as the emergence of the Anthropocene. Through its utility the plow has become one of the most influential instruments used in the farming community today. From the time people first began using plows, their usage had progressively increased. Farmers now rely heavily on plows to efficiently increase their crop production by burying weeds and previously planted crops and increased soil fertility. While historically most plows looked similar to this one, the farming equipment industry has exploded and today most plows are massive machines pulled by tractors used to cultivate hundreds of acres of farmland. The advancement of plows, although more efficient, have unfavorable impacts on the environment. However, plows similar to this single wheeled hoe have had a more positive effect on the environment through their promotion of organic farming methods that reduce the amount of toxins released into their environments. Our single wheeled hoe, thus, reflects a more hopeful view of the Anthropocene. Lately the focus has shifted to finding ways to use the plow responsibly to reduce its negative impacts. Recognizing the capacity of the land and shifting to the use of smaller plows such as this one could help reduce the emissions produced by large-scale farming. Farmers could also plant trees and shrubs surrounding their farms to reduce the wind erosion that is supported by the plowing 18 . These steps must be taken to reduce the impacts of the plow on the earth that can be seen through the Anthropocene. The plow has played a major role in the environmental history of Omaha through its contribution to the agriculture both within Omaha and the surrounding area. The effects of the plow must be considered with looking at the global history of the Anthropocene as it directly relates to the widespread shift towards farming which has greatly influenced our world.

Creator

Abigail Klick

Michaela Peck

Michaela Peck

Source

Bengtsson, Janne, Johan Ahnström, and Ann-Christin Weibull. "The effects of organic agriculture on biodiversity and abundance: a meta-analysis." Journal of Applied Ecology 42, no. 2 (2005): 261-69.

Bonney, Margaret Atherton ed., “Plowing in the Past: A Look at Early Farm Machinery,” The Goldfinch 2, no. 3 (February 1981): 8-11.Cunfer, Geoff. On The Great Plains. TX: Texas A&M University Press, 2005.

Ciampalini, Rossano, Paolo Billi, Giovanni Ferrari, Lorenzo Borsellini, and Stephane Follain. "Soil erosion induced by land use changes as determined by plough marks and field evidence in the Aksum area (Ethiopia)." Agriculture, Ecosystems, & Environment 146 (1) (2012): 197-208.

Gilbert, Natasha. "Summit Urged to Clean Up Farming." Nature 479, no. 7373 (2011): 279.

Gregg, Sara M. "From Breadbasket to Dust Bowl: Rural Credit, the World War I Plow-Up, and the Transformation of American Agriculture." Great Plains Quarterly 35, no. 2 (Spring 2015): 129-66.

Hester, R. E., and Roy M. Harrison. Environmental impacts of modern agriculture. Cambridge: RSC Publishing, 2012.

"History of the Wheel Hoe." Hoss Tools. https://hosstools.com/history-of-the-wheel-hoe/.

"Iron Age Farm and Garden Tools of 1903." Farm and Garden Tools of 1903, 1903, 108.

Kopsidis, Michael, and Nikolaus Wolf. “Agricultural Productivity Across Prussia During the Industrial Revolution: A Thünen Perspective.” The Journal of Economic History 72, no. 3 (2012): 634–70.

Lal, R., D. C. Reicosky, and J. D. Hanson. "Evolution of the plow over 10,000 years and the rationale for no-till farming." Soil and Tillage Research 93, no. 1 (March 2007): 1-12.

Luebke, Frederick C. Nebraska: an illustrated history. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005.

Moulton, Candy Vyvey. Roadside history of Nebraska. Missoula, MT: Mountain Press Pub. Co., 1997.

Percy, David O. "Ax or Plow?: Significant Colonial Landscape Alteration Rates in the Maryland and Virginia Tidewater." Agricultural History 66, no. 2 (1992): 66-74.

Prelinger Archives: The Plow That Broke the Plains (Part I) (1936). 1936. Accessed October 10, 2017.

Pryor, Frederic L. "The Invention of the Plow." Comparative Studies in Society and History 27,

no. 4 (1985): 727-43.

"The Garden Magazine." Grow Your Own Vegetables : 72.

Travelers' Railway Guide, Western Section (formerly the Rand-McNally Railway Guide). American Railway Guide Company, 1903.

Wills, Charles A. Historical Album of Nebraska. Brookfield, CT: Millbrook Press, 1995. "Parlin Orendorff and Martin Plow Co. Building." Omaha LHPC. Accessed October 03, 2017.

Wu, Xingkuan, and Hao Xie. 2011. Green Building Technologies and Materials : Selected, Peer Reviewed Papers From the 2011 International Conference on Green Building Technologies and Materials (GBTM 2011), May 30, 2011, Brussels, Belgium. Durtne-Zurich, Switzerland: Trans Tech Publications, 2011. (accessed October

10, 2017).

Bonney, Margaret Atherton ed., “Plowing in the Past: A Look at Early Farm Machinery,” The Goldfinch 2, no. 3 (February 1981): 8-11.Cunfer, Geoff. On The Great Plains. TX: Texas A&M University Press, 2005.

Ciampalini, Rossano, Paolo Billi, Giovanni Ferrari, Lorenzo Borsellini, and Stephane Follain. "Soil erosion induced by land use changes as determined by plough marks and field evidence in the Aksum area (Ethiopia)." Agriculture, Ecosystems, & Environment 146 (1) (2012): 197-208.

Gilbert, Natasha. "Summit Urged to Clean Up Farming." Nature 479, no. 7373 (2011): 279.

Gregg, Sara M. "From Breadbasket to Dust Bowl: Rural Credit, the World War I Plow-Up, and the Transformation of American Agriculture." Great Plains Quarterly 35, no. 2 (Spring 2015): 129-66.

Hester, R. E., and Roy M. Harrison. Environmental impacts of modern agriculture. Cambridge: RSC Publishing, 2012.

"History of the Wheel Hoe." Hoss Tools. https://hosstools.com/history-of-the-wheel-hoe/.

"Iron Age Farm and Garden Tools of 1903." Farm and Garden Tools of 1903, 1903, 108.

Kopsidis, Michael, and Nikolaus Wolf. “Agricultural Productivity Across Prussia During the Industrial Revolution: A Thünen Perspective.” The Journal of Economic History 72, no. 3 (2012): 634–70.

Lal, R., D. C. Reicosky, and J. D. Hanson. "Evolution of the plow over 10,000 years and the rationale for no-till farming." Soil and Tillage Research 93, no. 1 (March 2007): 1-12.

Luebke, Frederick C. Nebraska: an illustrated history. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005.

Moulton, Candy Vyvey. Roadside history of Nebraska. Missoula, MT: Mountain Press Pub. Co., 1997.

Percy, David O. "Ax or Plow?: Significant Colonial Landscape Alteration Rates in the Maryland and Virginia Tidewater." Agricultural History 66, no. 2 (1992): 66-74.

Prelinger Archives: The Plow That Broke the Plains (Part I) (1936). 1936. Accessed October 10, 2017.

Pryor, Frederic L. "The Invention of the Plow." Comparative Studies in Society and History 27,

no. 4 (1985): 727-43.

"The Garden Magazine." Grow Your Own Vegetables : 72.

Travelers' Railway Guide, Western Section (formerly the Rand-McNally Railway Guide). American Railway Guide Company, 1903.

Wills, Charles A. Historical Album of Nebraska. Brookfield, CT: Millbrook Press, 1995. "Parlin Orendorff and Martin Plow Co. Building." Omaha LHPC. Accessed October 03, 2017.

Wu, Xingkuan, and Hao Xie. 2011. Green Building Technologies and Materials : Selected, Peer Reviewed Papers From the 2011 International Conference on Green Building Technologies and Materials (GBTM 2011), May 30, 2011, Brussels, Belgium. Durtne-Zurich, Switzerland: Trans Tech Publications, 2011. (accessed October

10, 2017).

Collection

Citation

Abigail Klick

Michaela Peck, “Single-Wheel Hoe,” Omaha in the Anthropocene, accessed April 20, 2024, https://steppingintothemap.com/anthropocene/items/show/10.

Embed

Copy the code below into your web page