Nuclear Fallout Sign

Title

Nuclear Fallout Sign

Subject

The nuclear age began in the New Mexico desert on July 16, 1945 with a mushroom cloud of radioactive gases. The U.S. performed hundreds of nuclear bomb tests in the American Desert and Southern Pacific during the 1950s and 1960s. The radioactive fallout from these nuclear tests and the threat of nuclear war produced fear in America. FS2 fallout shelter signs remain as material evidence of this fear. Nuclear fears influenced environmentalism world-wide. In 1989, on the anniversary of the first atomic bomb, a large Omaha crowd protested at SAC. Today, we can still identify traces of this nuclear past in the earth’s crust. Few changes of the earth can be so directly observed and as a result, many scientists point to nuclear tests as the best starting point for the Anthropocene.

Description

The American bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki Japan on August 1945 inaugurated the nuclear age. Few historical transitions have such a clear beginning, and the consequences of that moment reverberate today (Figure 1). Fear of nuclear devastation and resulting radioactive fallout produced a culture of apocalyptic fear during the Cold War, and although nuclear annihilation no longer holds saw over our collective consciousness, nuclear power continues to be a factor in our globalized 21st century. Scientists continued to test nuclear weapons after 1945, to observe the consequences of nuclear detonations as well as the longer lasting effects of nuclear fallout. As a result of these tests, fear shifted from the apocalypse to more insidious threats. New invisible pollutants that were capable of not only impacting their health, but of irreversibly damaging the biosphere assumed center stage. This fear was a significant influence on the development of modern American environmentalism and the rising public influence of ecological sciences. Growing scientific awareness of global environmental change, the Anthropocene itself, were direct consequences of these historical changes.

This FS2 fallout shelter sign is an object that reveals much about the Anthropocene. It is a ten by fourteen-inch sign composed of galvanized steel (Figure 2). During 1962, the Department of Defense produced one million of these FS2 signs. (Civil Defense Museum) They can be found inside public fallout shelter facilities. The distribution of these signs was an important component of the National Fallout Shelter Program. The U.S. Department of Defense developed the National Fallout Shelter Program in an attempt to improve the dilemma of national security in the event of a nuclear attack. Later nuclear testing would demonstrate the inadequate ability to withstand an atomic bomb detonation or to effectively prevent radiation exposure. Interior signs had to be posted in a position of good visibility to the public and placed in such a way as to avoid vandalism. (Dept of Defense, 1977) FS1 signs were also developed to be posted on the exterior of fallout shelter facilities, these signs were slightly larger at fourteen by twenty inches and were made of the same galvanized steel. FS2 signs were emblazoned with the Civil Defense fallout shelter trefoil and adhesive tape displayed the capacity of the shelter and indicated their starting point. The civil defense fallout shelter symbol was designed to be readily identifiable from a long distance and visibly different than the radiation hazard symbol. Civil defense fallout shelter symbols represented safety while the older radiation symbol represented hazard (Figure 3). (ORAU) Public fear of nuclear attack stemmed not only from the thought of an initial blast that could vaporize an entire city but also from the notion of the invisible particles of radioactive fallout. FS2 signs were public representations of that fear.

A blinding flash of light followed by a towering mushroom cloud of radioactive gases signaled the first atomic bomb detonation in the desert of New Mexico on July 16, 1945. (Worster, 1977) The beginning of the nuclear age began with this detonation, while unconscious of the detrimental effects, nuclear states would persist with nuclear testing for decades. Previous technological developments such as railroads had already generated controversy regarding the effects on the environment, but the scale of a nuclear bomb’s impact produced a new, more resounding challenge. Could humanity be trusted with such power? The fear of rendering the earth a radioactive wasteland invoked fear in the public as well as in many of the primary developers of the atomic bomb. Oppenheimer, a leading Los Alamos scientist, was shaken to his core and questioned his humanity. (Fiege, 2012) Oppenheimer later reflected on this experience by reiterating a quote from the Bhagavad Gita, “now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.” (Atomic Archive) As the United States continued testing in American deserts, scientists confirmed the catastrophic destruction of explosions, as well as radionuclide drift. For the vast majority of Americans, including “downwinders” living in the path of airborne radioactive particulates, recognition of this second threat emerged very slowly.

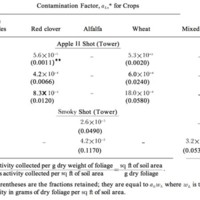

Among the first public intellectual to sound the alarm about the effects of radiation was Barry Commoner. Government scientists conducted studies, but were typically reticent to publicize them for reasons of “national security” A significant shift occurred in 1963 when Eugene P. Odum presented several claims about the ecological effects of nuclear war in the closing of the Ecological Society of America’s Symposium. Odum claimed that the removal of biomass from the soil as a result of coniferous and deciduous tree species’ sensitivity to ionizing radiation would likely result in an increase in nutrient loss from several ecosystems. Grover and Harwell used atmospheric tests to provide evidence of the limited plausibility for plant recovery following a nuclear war (Grover and Harwell, 1985). Reestablishment of several larger plant species would be dependent on seed banks, as well as the acute and chronic stresses acting on the particular environment (Figure 4). Lakes, estuaries, and tropical forests are among the environments that experience change in temperature, sunlight reduction, precipitation reduction, less significantly fallout radiation, and increased UV-B from ozone depletion as a result of nuclear bomb detonation. Grover and Harwell conclude that a nuclear war imposes the same environmental effects that alternative forms of man’s exploitation of nature can impose, but the scale is drastically larger. Reestablishment of several larger plant species would be dependent on seed banks, as well as the acute and chronic stresses acting on the particular environment. Lakes, estuaries, and tropical forests are among the environments that experience change in temperature, sunlight reduction, precipitation reduction, fallout radiation (small effect), and increased UV-B from ozone depletion as a result of nuclear bomb detonation. Grover and Harwell conclude that a nuclear war imposes the same environmental effects that alternative forms of man’s exploitation of nature can impose, but the scale is drastically larger. The ecological consequences of nuclear war must be of higher concern than our global security. (Grover and Harwell, 1985) Scientific evidence of fallout pollution inspired a public fear; ecological studies of the consequences of nuclear warfare made the public realize that ecological mindfulness of “invisible pollutants” was necessary to avoid environmental devastation.

It was perhaps no coincidence that fear of invisible pollutants and the rise of ecological thinking arose in the 1960s. Nuclear fallout wasn’t the first invisible pollutant that had persistently found its way into food chains and impacted human health. In 1962, Rachel Carson published her blockbuster expose about the effects of pesticide use, called Silent Spring. In this book, she demonstrated how dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane (DDT) moved through food webs, polluting the environment and threatening public health. Exposure to fallout played into similar fears. In the years following the Hiroshima detonation, many survivors developed leukemia. (Carson, 2015) The development of cancer can arise from diverse exposure to mutagens, but indelible evidence of Leukemia development just two years after the Japan nuclear attack demonstrates the extent of radiation-induced health detriments that arise from nuclear bomb detonations. (K1 Project)

As scientists, particularly ecologists, uncovered more of the human and environmental consequences of fallout, public sentiment shifted. Collaboration between scientists and major publications was necessary to overcome public apathy. Scientists began drawing information on the ecological impact of nuclear explosions from test sites in the American desert and the South Pacific. Reader’s Digest began to publish doomsday articles in the late 1940s, these publications had titles like “What the Atom Bomb Would Do to Us” and “What the Atomic Bomb Really Did.” (Egan, 2009) These articles presented scientific findings in the context of the atomic bomb used in Hiroshima, even though other more lethal bombs had subsequently been developed and tested. In 1947, Reader’s Digest collaborated with credible scientists to describe a realistic hypothetical nuclear bomb attack in the heart of major American cities with the publication of “Mist of Death Over New York.” They began by describing the violent deaths of those in the explosive zone. What resonated more with the public was the description of those who managed to escape the blast but were struck with radiation sickness and eventually died from the exposure to the gamma rays. The public began to understand the health repercussions that would result from fallout exposure, which included sterility, birth rate decline, and limited access to essential resources. From that understanding arose a great public fear about said repercussions. Politically active scientists had become an instrument of peace with the increase in the scale of hazards. (Egan, 2009) Politicized fear had become a potent agent for change, one that could push the public to demand environmental sustainability.

Fallout shelters represent this transition. Fallout shelters were not built to withstand the impact of a nuclear explosion; they were made to prevent exposure to radioactive fallout. The Department of Defense issued twenty-five million booklets on the construction parameters for fallout shelters. (Berrien, Schulman and Amarel, 1963) Private fallout shelters were not common; among people that had the financial means to build a fallout shelter, only a small percentage built them. Failure to build private fallout shelters wasn’t due to their lack of protection, but due to the attitude that the “government should place a greater emphasis on efforts to secure the peace through diplomacy.” (Berrien, Schulman and Amarel, 1963) In an attempt to encourage the public to build private fallout shelters, The Science News-Letter described the construction of fallout shelters as dual purpose rooms in the lower level of a home. Several scientists studied the effectiveness of fallout shelters to provide a safe environment in the event of a nuclear attack while performing nuclear bomb testing at the Nevada site. The Federal Department of Defense Administration conducted Operation Plumbbob; after testing several fallout shelters in the event of a nuclear bomb, the examiners concluded that fallout shelters were not always effective at preventing the respiratory hazard caused by dust leakage. (White, Wetherbe and Goldzien, 1957) Initially, the government promoted fallout shelters as a temporary solution to the impending war. Nevertheless, as the public became more aware of the ineffectiveness and lack of the feasibility of fallout shelters, they demanded social change.

Omaha, and Nebraska in general, have had an interesting history with regards to the threat of nuclear fallout, and thus are major players in the fight against nuclear weapons. During the Cold War, Omaha and its surrounding areas were strategic targets for nuclear attack due to military installations such as the Offutt military base, which houses the Strategic Air Command (SAC) for the United States. Additionally, SAC began construction of Atlas Missile Complexes in the areas surrounding Omaha and Lincoln in 1959. (Neb Educational Telecommunications) These developments prompted organizations such as the Committee for Nonviolent Action (CNVA) to organize protests at SAC to denounce the use of nuclear weapons and encourage resistance against the sites’ construction (Figure 5). Through acts of civil disobedience, protesters would attempt to stall the construction however they could, by blocking trucks, for instance. (Neb Educational Telecommunications) There was also a major campaign to encourage civilians to resist the construction: suggesting that the people can refuse to work on the construction, scientists can refuse to create such weapons, unions can strike against military projects, and church members can use their faith as a means to limit their involvement in these military projects. (Neb Educational Telecommunications) Nebraskans feared that cities like Omaha and Lincoln would become targets if nuclear war was to break out, and the resulting fallout would devastate human health and the environment for generations. In a letter to President Eisenhower in 1959, A.J. Muste of the CNVA argued:

"Man did not create the land. It was given to him as a heritage to use for the production of food and clothing and shelter, and that he might enjoy its beauty. Men are now preparing destruction, which can hardly be called war in the old sense at all, which may actually wipe out vegetation and poison the soil." (Nebraska Historical Society)

In this small way, Omaha took part in a much larger social movement intended to call attention to this new, catastrophic threat.

Human nuclear activity has changed the world in ways unlike any other time in recorded history. The mass proliferation of particles in the atmosphere from nuclear weapons has changed the world in ways that are only possible through human action, which is why the nuclear age is the epitome of the Anthropocene. With the onset of the nuclear age we started a new epoch, the Anthropocene, where the evidence of our profound impact is indelible. The proliferation of radioactive particles from nuclear bomb detonations serves as the best candidate for the golden spike of the Anthropocene. We have observed cycles of elevated carbon dioxide, elevated animal extinctions, and changing levels of nitrogen and phosphorus in the soil during several time periods. (Carrington, 2016) Yet, in no other time have we observed the presence of ionizing radioactive particles in the atmosphere and the associated environmental and health consequences. We live in an age where our actions have lasting consequences. The Anthropocene is only possible with the rise of the environmentalist movement; it is only after reflecting on the interconnectivity between man and the environment that we can begin to define the Anthropocene.

This FS2 fallout shelter sign is an object that reveals much about the Anthropocene. It is a ten by fourteen-inch sign composed of galvanized steel (Figure 2). During 1962, the Department of Defense produced one million of these FS2 signs. (Civil Defense Museum) They can be found inside public fallout shelter facilities. The distribution of these signs was an important component of the National Fallout Shelter Program. The U.S. Department of Defense developed the National Fallout Shelter Program in an attempt to improve the dilemma of national security in the event of a nuclear attack. Later nuclear testing would demonstrate the inadequate ability to withstand an atomic bomb detonation or to effectively prevent radiation exposure. Interior signs had to be posted in a position of good visibility to the public and placed in such a way as to avoid vandalism. (Dept of Defense, 1977) FS1 signs were also developed to be posted on the exterior of fallout shelter facilities, these signs were slightly larger at fourteen by twenty inches and were made of the same galvanized steel. FS2 signs were emblazoned with the Civil Defense fallout shelter trefoil and adhesive tape displayed the capacity of the shelter and indicated their starting point. The civil defense fallout shelter symbol was designed to be readily identifiable from a long distance and visibly different than the radiation hazard symbol. Civil defense fallout shelter symbols represented safety while the older radiation symbol represented hazard (Figure 3). (ORAU) Public fear of nuclear attack stemmed not only from the thought of an initial blast that could vaporize an entire city but also from the notion of the invisible particles of radioactive fallout. FS2 signs were public representations of that fear.

A blinding flash of light followed by a towering mushroom cloud of radioactive gases signaled the first atomic bomb detonation in the desert of New Mexico on July 16, 1945. (Worster, 1977) The beginning of the nuclear age began with this detonation, while unconscious of the detrimental effects, nuclear states would persist with nuclear testing for decades. Previous technological developments such as railroads had already generated controversy regarding the effects on the environment, but the scale of a nuclear bomb’s impact produced a new, more resounding challenge. Could humanity be trusted with such power? The fear of rendering the earth a radioactive wasteland invoked fear in the public as well as in many of the primary developers of the atomic bomb. Oppenheimer, a leading Los Alamos scientist, was shaken to his core and questioned his humanity. (Fiege, 2012) Oppenheimer later reflected on this experience by reiterating a quote from the Bhagavad Gita, “now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.” (Atomic Archive) As the United States continued testing in American deserts, scientists confirmed the catastrophic destruction of explosions, as well as radionuclide drift. For the vast majority of Americans, including “downwinders” living in the path of airborne radioactive particulates, recognition of this second threat emerged very slowly.

Among the first public intellectual to sound the alarm about the effects of radiation was Barry Commoner. Government scientists conducted studies, but were typically reticent to publicize them for reasons of “national security” A significant shift occurred in 1963 when Eugene P. Odum presented several claims about the ecological effects of nuclear war in the closing of the Ecological Society of America’s Symposium. Odum claimed that the removal of biomass from the soil as a result of coniferous and deciduous tree species’ sensitivity to ionizing radiation would likely result in an increase in nutrient loss from several ecosystems. Grover and Harwell used atmospheric tests to provide evidence of the limited plausibility for plant recovery following a nuclear war (Grover and Harwell, 1985). Reestablishment of several larger plant species would be dependent on seed banks, as well as the acute and chronic stresses acting on the particular environment (Figure 4). Lakes, estuaries, and tropical forests are among the environments that experience change in temperature, sunlight reduction, precipitation reduction, less significantly fallout radiation, and increased UV-B from ozone depletion as a result of nuclear bomb detonation. Grover and Harwell conclude that a nuclear war imposes the same environmental effects that alternative forms of man’s exploitation of nature can impose, but the scale is drastically larger. Reestablishment of several larger plant species would be dependent on seed banks, as well as the acute and chronic stresses acting on the particular environment. Lakes, estuaries, and tropical forests are among the environments that experience change in temperature, sunlight reduction, precipitation reduction, fallout radiation (small effect), and increased UV-B from ozone depletion as a result of nuclear bomb detonation. Grover and Harwell conclude that a nuclear war imposes the same environmental effects that alternative forms of man’s exploitation of nature can impose, but the scale is drastically larger. The ecological consequences of nuclear war must be of higher concern than our global security. (Grover and Harwell, 1985) Scientific evidence of fallout pollution inspired a public fear; ecological studies of the consequences of nuclear warfare made the public realize that ecological mindfulness of “invisible pollutants” was necessary to avoid environmental devastation.

It was perhaps no coincidence that fear of invisible pollutants and the rise of ecological thinking arose in the 1960s. Nuclear fallout wasn’t the first invisible pollutant that had persistently found its way into food chains and impacted human health. In 1962, Rachel Carson published her blockbuster expose about the effects of pesticide use, called Silent Spring. In this book, she demonstrated how dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane (DDT) moved through food webs, polluting the environment and threatening public health. Exposure to fallout played into similar fears. In the years following the Hiroshima detonation, many survivors developed leukemia. (Carson, 2015) The development of cancer can arise from diverse exposure to mutagens, but indelible evidence of Leukemia development just two years after the Japan nuclear attack demonstrates the extent of radiation-induced health detriments that arise from nuclear bomb detonations. (K1 Project)

As scientists, particularly ecologists, uncovered more of the human and environmental consequences of fallout, public sentiment shifted. Collaboration between scientists and major publications was necessary to overcome public apathy. Scientists began drawing information on the ecological impact of nuclear explosions from test sites in the American desert and the South Pacific. Reader’s Digest began to publish doomsday articles in the late 1940s, these publications had titles like “What the Atom Bomb Would Do to Us” and “What the Atomic Bomb Really Did.” (Egan, 2009) These articles presented scientific findings in the context of the atomic bomb used in Hiroshima, even though other more lethal bombs had subsequently been developed and tested. In 1947, Reader’s Digest collaborated with credible scientists to describe a realistic hypothetical nuclear bomb attack in the heart of major American cities with the publication of “Mist of Death Over New York.” They began by describing the violent deaths of those in the explosive zone. What resonated more with the public was the description of those who managed to escape the blast but were struck with radiation sickness and eventually died from the exposure to the gamma rays. The public began to understand the health repercussions that would result from fallout exposure, which included sterility, birth rate decline, and limited access to essential resources. From that understanding arose a great public fear about said repercussions. Politically active scientists had become an instrument of peace with the increase in the scale of hazards. (Egan, 2009) Politicized fear had become a potent agent for change, one that could push the public to demand environmental sustainability.

Fallout shelters represent this transition. Fallout shelters were not built to withstand the impact of a nuclear explosion; they were made to prevent exposure to radioactive fallout. The Department of Defense issued twenty-five million booklets on the construction parameters for fallout shelters. (Berrien, Schulman and Amarel, 1963) Private fallout shelters were not common; among people that had the financial means to build a fallout shelter, only a small percentage built them. Failure to build private fallout shelters wasn’t due to their lack of protection, but due to the attitude that the “government should place a greater emphasis on efforts to secure the peace through diplomacy.” (Berrien, Schulman and Amarel, 1963) In an attempt to encourage the public to build private fallout shelters, The Science News-Letter described the construction of fallout shelters as dual purpose rooms in the lower level of a home. Several scientists studied the effectiveness of fallout shelters to provide a safe environment in the event of a nuclear attack while performing nuclear bomb testing at the Nevada site. The Federal Department of Defense Administration conducted Operation Plumbbob; after testing several fallout shelters in the event of a nuclear bomb, the examiners concluded that fallout shelters were not always effective at preventing the respiratory hazard caused by dust leakage. (White, Wetherbe and Goldzien, 1957) Initially, the government promoted fallout shelters as a temporary solution to the impending war. Nevertheless, as the public became more aware of the ineffectiveness and lack of the feasibility of fallout shelters, they demanded social change.

Omaha, and Nebraska in general, have had an interesting history with regards to the threat of nuclear fallout, and thus are major players in the fight against nuclear weapons. During the Cold War, Omaha and its surrounding areas were strategic targets for nuclear attack due to military installations such as the Offutt military base, which houses the Strategic Air Command (SAC) for the United States. Additionally, SAC began construction of Atlas Missile Complexes in the areas surrounding Omaha and Lincoln in 1959. (Neb Educational Telecommunications) These developments prompted organizations such as the Committee for Nonviolent Action (CNVA) to organize protests at SAC to denounce the use of nuclear weapons and encourage resistance against the sites’ construction (Figure 5). Through acts of civil disobedience, protesters would attempt to stall the construction however they could, by blocking trucks, for instance. (Neb Educational Telecommunications) There was also a major campaign to encourage civilians to resist the construction: suggesting that the people can refuse to work on the construction, scientists can refuse to create such weapons, unions can strike against military projects, and church members can use their faith as a means to limit their involvement in these military projects. (Neb Educational Telecommunications) Nebraskans feared that cities like Omaha and Lincoln would become targets if nuclear war was to break out, and the resulting fallout would devastate human health and the environment for generations. In a letter to President Eisenhower in 1959, A.J. Muste of the CNVA argued:

"Man did not create the land. It was given to him as a heritage to use for the production of food and clothing and shelter, and that he might enjoy its beauty. Men are now preparing destruction, which can hardly be called war in the old sense at all, which may actually wipe out vegetation and poison the soil." (Nebraska Historical Society)

In this small way, Omaha took part in a much larger social movement intended to call attention to this new, catastrophic threat.

Human nuclear activity has changed the world in ways unlike any other time in recorded history. The mass proliferation of particles in the atmosphere from nuclear weapons has changed the world in ways that are only possible through human action, which is why the nuclear age is the epitome of the Anthropocene. With the onset of the nuclear age we started a new epoch, the Anthropocene, where the evidence of our profound impact is indelible. The proliferation of radioactive particles from nuclear bomb detonations serves as the best candidate for the golden spike of the Anthropocene. We have observed cycles of elevated carbon dioxide, elevated animal extinctions, and changing levels of nitrogen and phosphorus in the soil during several time periods. (Carrington, 2016) Yet, in no other time have we observed the presence of ionizing radioactive particles in the atmosphere and the associated environmental and health consequences. We live in an age where our actions have lasting consequences. The Anthropocene is only possible with the rise of the environmentalist movement; it is only after reflecting on the interconnectivity between man and the environment that we can begin to define the Anthropocene.

Creator

Jesus Perez

Wade Peyou

Wade Peyou

Source

Berrien, F. K., Carol Schulman, and Marianne Amarel. "The Fallout-Shelter Owners: A Study of

Attitude Formation." The Public Opinion Quarterly 27, no. 2 (1963): 206-16. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2746915.

Boyer, Paul . By the Bomb's Early Light: American Thought and Culture at the Dawn of the

Atomic Age. University of North Carolina Press, 1994.

Carrington, Damian. "The Anthropocene epoch: scientists declare dawn of human-influenced

age." The Guardian. August 29, 2016. Accessed December 10, 2017.

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/aug/29/declare-anthropocene-epoch-experts-urge-geological-congress-human-impact-earth.

Carson, Rachel. Silent Spring. London: Penguin Books, in association with Hamish Hamilton,

2015.

"Civil Defense Fallout Shelter Sign." Civil Defense Fallout Shelter Sign (ca. 1960s). May 24,

2011. Accessed November 08, 2017. https://www.orau.org/ptp/collection/civildefense/sheltersign.htm.

Egan, Michael. Barry Commoner and the Science of Survival: The Remaking of American

Environmentalism. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009.

"Fallout Shelters' "Lived-in" Look." The Science News-Letter 80, no. 16 (1961): 258-59.

doi:10.2307/3943848.

Fiege, Mark. The Republic of Nature: An Environmental History of the United States. Seattle,

Washington: University of Washington Press, 2012.

Frame , P. "Radiation Warning Symbol (Trefoil)." Origin of the Radiation Warning Sign

(Trefoil). Accessed November 07, 2017. http://www.orau.org/ptp/articlesstories/radwarnsymbstory.htm.

Glass, Bentley. "The Biology of Nuclear War." The American Biology Teacher 24, no. 6 (1962):

407-25. doi:10.2307/4440018.

Grover, Herbert D., and Mark A. Harwell. "Biological Effects of Nuclear War II: Impact on the

Biosphere." BioScience 35, no. 9 (1985): 576-83. doi:10.2307/1309966.

Interactive Media Group - Nebraska Educational Telecommunications. NebraskaStudies.Org.

Accessed December 10, 2017.

http://www.nebraskastudies.org/0900/frameset_reset.html?http%3A%2F%2Fwww.nebr

skastudies.org%2F0900%2Fstories%2F0901_0126.html.

"J. Robert Oppenheimer "Now I am become death..."." J. Robert Oppenheimer | Media Gallery.

Accessed December 10, 2017. http://www.atomicarchive.com/Movies/Movie8.shtml.

"Little Boy and Fat Man." Atomic Heritage Foundation. July 23, 2014. Accessed November 06,

2017. https://www.atomicheritage.org/history/little-boy-and-fat-man.

Muste, Abraham. Swarthmore College Peace Collection. 1920-1967. Nebraska Historical

Society. Accessed November 4, 2017.

http://www.nebraskastudies.org/0900/media/0904_0704letter.pdf.

Nebraska Educational Telecommunications. “Missiles on Land and Sea: Protests against Nuclear

War.” Nebraska Studies 1950-1974. 2001. Accessed November 4, 2017. http://www.nebraskastudies.org/0900/frameset_reset.html?http://www.nebraskastudies.org/0900/stories/0901_0126.html.

Prăvălie, Remus. "Nuclear Weapons Tests and Environmental Consequences: A Global

Perspective." Ambio. October 2014. Accessed October 10, 2017.

"Standard Fallout Shelter Signs ." Fallout Shelter Sign Page. Accessed October 08, 2017.

http://www.civildefensemuseum.com/signs/.

United Press International. “208 Detained in Nuclear Protest At Air Force Base Near Omaha. “

The New York Times. August 8, 1983. Accessed November 4, 2017. http://www.nytimes.com/1983/08/08/us/208-detained-in-nuclear-protest-at-air-force-base-near-omaha.html.

United States of America. Defense Civil Preparedness Agency. Department of Defense . October

1977. Accessed November 3, 2017. http://www.civildefensemuseum.com/signs/CPG1-19A.pdf.

United States of America. “EPA Facts About Strontium-90.” Environmental Protection Agency.

Accessed November 4, 2017. https://semspub.epa.gov/work/HQ/175430.pdf.

United States of America. The Internal Environment of Underground Structures Subjected to

Nuclear Blast: Operation Plumbbob, Project 33.5. By C. S. White, M. B. Wetherbe, and V. C. Goldizen. Albuquerque, NM, NM: Lovelace

Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 1957.

Woodwell, G. M. Ecological Effects of Nuclear War . Vol. 917. (1963): Brookhaven National

Laboratory.

Worster, Donald. Nature's Economy: A History of Ecological Ideas . Cambridge University

Press, 1977.

Attitude Formation." The Public Opinion Quarterly 27, no. 2 (1963): 206-16. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2746915.

Boyer, Paul . By the Bomb's Early Light: American Thought and Culture at the Dawn of the

Atomic Age. University of North Carolina Press, 1994.

Carrington, Damian. "The Anthropocene epoch: scientists declare dawn of human-influenced

age." The Guardian. August 29, 2016. Accessed December 10, 2017.

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/aug/29/declare-anthropocene-epoch-experts-urge-geological-congress-human-impact-earth.

Carson, Rachel. Silent Spring. London: Penguin Books, in association with Hamish Hamilton,

2015.

"Civil Defense Fallout Shelter Sign." Civil Defense Fallout Shelter Sign (ca. 1960s). May 24,

2011. Accessed November 08, 2017. https://www.orau.org/ptp/collection/civildefense/sheltersign.htm.

Egan, Michael. Barry Commoner and the Science of Survival: The Remaking of American

Environmentalism. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009.

"Fallout Shelters' "Lived-in" Look." The Science News-Letter 80, no. 16 (1961): 258-59.

doi:10.2307/3943848.

Fiege, Mark. The Republic of Nature: An Environmental History of the United States. Seattle,

Washington: University of Washington Press, 2012.

Frame , P. "Radiation Warning Symbol (Trefoil)." Origin of the Radiation Warning Sign

(Trefoil). Accessed November 07, 2017. http://www.orau.org/ptp/articlesstories/radwarnsymbstory.htm.

Glass, Bentley. "The Biology of Nuclear War." The American Biology Teacher 24, no. 6 (1962):

407-25. doi:10.2307/4440018.

Grover, Herbert D., and Mark A. Harwell. "Biological Effects of Nuclear War II: Impact on the

Biosphere." BioScience 35, no. 9 (1985): 576-83. doi:10.2307/1309966.

Interactive Media Group - Nebraska Educational Telecommunications. NebraskaStudies.Org.

Accessed December 10, 2017.

http://www.nebraskastudies.org/0900/frameset_reset.html?http%3A%2F%2Fwww.nebr

skastudies.org%2F0900%2Fstories%2F0901_0126.html.

"J. Robert Oppenheimer "Now I am become death..."." J. Robert Oppenheimer | Media Gallery.

Accessed December 10, 2017. http://www.atomicarchive.com/Movies/Movie8.shtml.

"Little Boy and Fat Man." Atomic Heritage Foundation. July 23, 2014. Accessed November 06,

2017. https://www.atomicheritage.org/history/little-boy-and-fat-man.

Muste, Abraham. Swarthmore College Peace Collection. 1920-1967. Nebraska Historical

Society. Accessed November 4, 2017.

http://www.nebraskastudies.org/0900/media/0904_0704letter.pdf.

Nebraska Educational Telecommunications. “Missiles on Land and Sea: Protests against Nuclear

War.” Nebraska Studies 1950-1974. 2001. Accessed November 4, 2017. http://www.nebraskastudies.org/0900/frameset_reset.html?http://www.nebraskastudies.org/0900/stories/0901_0126.html.

Prăvălie, Remus. "Nuclear Weapons Tests and Environmental Consequences: A Global

Perspective." Ambio. October 2014. Accessed October 10, 2017.

"Standard Fallout Shelter Signs ." Fallout Shelter Sign Page. Accessed October 08, 2017.

http://www.civildefensemuseum.com/signs/.

United Press International. “208 Detained in Nuclear Protest At Air Force Base Near Omaha. “

The New York Times. August 8, 1983. Accessed November 4, 2017. http://www.nytimes.com/1983/08/08/us/208-detained-in-nuclear-protest-at-air-force-base-near-omaha.html.

United States of America. Defense Civil Preparedness Agency. Department of Defense . October

1977. Accessed November 3, 2017. http://www.civildefensemuseum.com/signs/CPG1-19A.pdf.

United States of America. “EPA Facts About Strontium-90.” Environmental Protection Agency.

Accessed November 4, 2017. https://semspub.epa.gov/work/HQ/175430.pdf.

United States of America. The Internal Environment of Underground Structures Subjected to

Nuclear Blast: Operation Plumbbob, Project 33.5. By C. S. White, M. B. Wetherbe, and V. C. Goldizen. Albuquerque, NM, NM: Lovelace

Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 1957.

Woodwell, G. M. Ecological Effects of Nuclear War . Vol. 917. (1963): Brookhaven National

Laboratory.

Worster, Donald. Nature's Economy: A History of Ecological Ideas . Cambridge University

Press, 1977.

Rights

The Durham Museum

Collection

Citation

Jesus Perez

Wade Peyou, “Nuclear Fallout Sign,” Omaha in the Anthropocene, accessed April 23, 2024, https://steppingintothemap.com/anthropocene/items/show/11.

Embed

Copy the code below into your web page