Plastic Cup

Title

Plastic Cup

Subject

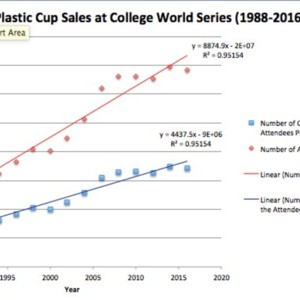

Omaha has been home to the College World Series since 1950. This great baseball event brings in thousands of fans from across the world every summer. Consumers buy souvenirs like this cup at high volumes to bring home with them from the event. When reused or recycled, consumer plastics like this cup can drastically decrease waste sent to landfills. If patrons throw this cup away, however, its durability ensures long-lasting environmental impact. Up to 79% of plastic waste is disposed in landfills or the environment. Because of this, plastic pollution has a significant negative impact on the environment. Consumer plastic is now a bedrock material of the Anthropocene.

Description

Since 1967, the College World Series has drawn countless baseball fans from across the country to the streets of Omaha for two weeks every summer. They arrive as consumers both of baseball and the countless products they use, abandon, or take home as souvenirs. One of these objects is a plastic souvenir cup from the 1988 CWS. This plastic cup is not an extraordinary object, however, it is imperative to look beyond the surface and imagine what this object truly represents: the global use of consumer plastic both in Omaha and worldwide. Consumer plastics have had dramatic effects on the environment on both a local and global scale; however, they have also positively contributed to progress toward a more sustainable society. Our object points to the fact that while plastics can embody negative effects of the Anthropocene, they can also exemplify the positive aspects of humanity’s technological and scientific development.

Plastic is a polymer; a substance made up of repeating chemical units. As explained by Andrea Sella, a professor at University College London, “you take a simple organic molecule react it with yourself again and again and again, a little bit like a bicycle chain; you attach one link, and you click on the next one and the next one… almost ad infinitum.” (Knight, 2014) Plastics were not the first manufactured polymer, though. While looking for a cheap substitute for ivory for use in billiards balls, John Wesley Hyatt created the first synthetic polymer in 1869. This scientific innovation was the first of its kind, and importantly did not require the contribution of the products directly extracted from natural resources. (SHI, 2016) Humans now had the complete control of the process for the production of plastic polymers.

Hyatt’s substance was an early predecessor today’s durable plastic. The more immediate precursors to modern-day plastics were substances retrospectively known as “proto-plastics”, such as vulcanized rubber produced in the mid-19th century. (Fenichell, 1996) During World War II, shortages in rubber, brass and aluminum incentivized the substitution of plastic, which became favored following the war for many of its newfound uses. Plastic production expanded exponentially during and after the war. (Meikle, 1995) During WWII, production of synthetic plastic within the United States of America increased by 300%. (SHI, 2016) Due to its immense popularity and economic potential, companies began investing in plastic research to produce new types of plastics “for their own sake and worried about finding uses for them later.” (SHI, 2016) The consumerist vision of plastic had begun.

Innovations of plastics have drastically changed its properties. Modern plastics are now heat resistant, elastic, and can avoid scratches and cracking. These new updates add unknown chemicals to the polymerization process. New societal fears about potential toxicity and easy disposability of plastics have begun to turn plastics use into a cultural and environmental question. (Mossman, 2008) Plastic’s main ingredient is one of the most precious materials on earth: oil. This sought after commodity price has fluctuated greatly through the years, and has affected the progression of plastic research and societal acceptance. (Swallow, 1951)

Plastic “combines the ultimate twentieth-century characteristics - artificiality, disposability, and synthesis - all rolled into one.” (Mossman, 2008) American society now has unlimited access to plastic goods ranging from hula-hoops to lawn furniture. Susan Frienkel describes the United States’ obsession with plastic simply. “In product after product, market after market, plastics challenged traditional materials and won, taking the place of steel in cars, paper and glass in packaging, and wood in furniture.” (Freinkel, 2011) Americans integrated plastic into nearly every aspect of their lives and it is now one of the primary materials in American everyday life.

The industrial and consumer growth has had profound environmental implications. Environmentalists describe plastic as “one of the most ubiquitous and long lasting recent changes to the surface of our planet.” (Fischer, 2017) The explosion of plastics usage has largely paralleled the exponential growth referred to by Anthropocene scholars as the Great Acceleration. Plastic became common in the 1940s, and its use has increased exponentially ever since. The amount of plastic created in the first ten years of this century is greater than the amount produced in the prior century. (Fischer, 2017) Additionally, numbers skyrocketed between the 20th and 21st centuries. In 2007, 230 million tons of plastic were produced globally. (Mossman, 2008) Consumer demand propelled its production and disposal of this product into a great hindrance upon the global environment.

Plastic’s effect upon the earth system is unprecedented. While people can theoretically reuse it, most plastics are created for single-use product, such as disposable water bottles. This has led to incredible amounts of plastics in landfills and the oceans which will remain there unless otherwise removed by humans. Plastics debris found in oceans has rattled the complete acceptance of plastic within American culture. (Meikle, 1997) Plastic objects are held as having three different ends; recycling or reprocessing, thermal destruction which is often done without energy recovery, or disposal in either “a managed system, such as sanitary landfills, or uncontained in open dumps or in the natural environment.” (Geyer, Jambek and Law, 2017)

The image of sea life trapped in plastic has achieved iconic status in environmental critiques of consumerism. Additionally, the negative impact of plastics upon the ocean is not limit to its solidified state. Oil, the primary ingredient of plastic, is always a danger to spilling within some of the world’s major bodies of water. This impending risk has become a reality on numerous occasions, hindering and destroying oceanic life as society knows it.

Furthermore, scientists have discovered that chemicals used in plastics production are detrimental to humans when absorbed, often through consumption of foods and beverages in plastic packaging. (Fischer, 2017) Some of the commonly used chemicals are hazardous due to their toxicity, sensitization, ability to corrode the skin and eyes, carcinogenicity, mutagenicity, and teratogenicity. (Wiberg, 1976) All organisms are susceptible to these effect, not just humans. Due to the great penetration of plastics into everyday life of humankind plastics are a negative component of the everyday life of oceanic, avian, and terrestrial animals. (Wallace, 2016) Due to its shear longevity, the negative implications of plastics within the earth system is significant and perpetual.

On the other hand, plastic does have many benefits. According to the American Chemistry Council, which is admittedly the research arm of the plastics industry, it is beneficial to the environment. Its high strength-weight ratio allows for lighter packaging, resulting lower fuel usage during transportation of products. It takes two pounds of plastic to create an 8 gallon container. The same container would require three pounds of aluminum, eight pounds of steel, or 27 pounds of glass. (ACC, 2018) Plastic products can often reused, recycled, or reimagined as containers, rug fibers, composite lumber, or new pipe products. (EPA, 2016) Plastics-to-oil, or PTO, production is a process which has recently begun gaining traction as a way to gain use from plastic in situations where it is not feasible to recycle plastics. PTO facilities first heat plastic to a gaseous state and then distill the gas into liquid fuel for sale or further refinement. (ACC, 2014) Researchers who represent the plastics lobby believe PTO facilities could divert 20% of the 32.5 million tons of plastic that enter US landfills each year and turn it into fuel.

Plastic is often superior to its substitutes due to superior efficiency, both in terms of money and energy. While plastic began to be widely during WWII due to shortages in other materials, its use continued postwar because for many uses it was cheaper than the original materials. (Meikle, 1995) Plastic use lowers costs for distributors and retailers, thereby lowering the cost of goods packaged in it. (Belasco and Bronner, 2017) A 2010 study conducted by Plastics Europe, a research arm of a plastics lobby, found that the “substitution of plastic products by other materials wherever possible would need about 57% more energy than currently used in the total life cycle of all plastic products today”- the same amount of energy carried by approximately 205 oil tankers. That action would increase would increase annual greenhouse gas emissions by 124 megatons- about the same as Belgium’s total CO₂ emissions in 2000. This is because plastics are less costly to produce and use in terms of energy used. Only 18% of plastic’s energy demand is linked to the period of time the product is being used for its intended purpose relative to an average of 24% for other materials, largely because of its weight savings in packaging and the resulting lowered transportation energy costs. (Denkstatt GmbH, 2010) This is because of plastic’s relatively high strength to weight ratio not found in other common packaging materials. (Andrady and Neal, 2009) These numbers are easily demonstrated in the figure “Life Cycle Energy Consumption of Plastic Products and Their Potential Substitutes” found in the Figure 2. It was estimated that the emissions savings of using plastic products in 2007 rather than its substitutes were 5-9 times the emissions used to produce and dispose of plastic. Furthermore, the negative environmental effects of plastics have often been greatly exaggerated; only 1.3% of an average person’s carbon footprint comes from plastic products whereas recreation and leisure accounts for the largest share of the carbon footprint at 18%. (Andrady and Neal, 2009) It is worth noting again that pretty much all benefits research is done on the behalf of plastics lobbies.

One might ponder the significance of plastic cup in a history museum, as one should. Could it be the familiarity of the object that makes you question its importance? For most people, a common plastic cup from the 1988 College World Series may not reveal much history. In fact, the true historical value of theses cups is surprisingly within the plastic of which it was made. It’s undeniable that humans see and use plastics in almost every aspect of our lives yet the importance of plastic is often overlooked because of its commonality. Moreover, the history of plastic illustrates an ongoing, interconnected relationship between humans, objects, and nature. In fact, Omaha is a great example of this interconnected relationship as it harks back to when railways were used as means for transporting goods and commodities between the east and west. Think about where this plastic originated (St. Louis, Missouri), how it was made, how was it brought to Omaha, what resources were needed to make it, how it was disposed, and how has nature become affected as a result. Plastic has evolved throughout history in order to better benefit human use. However, it is important to understand that with all benefits come costs. This cup emphasizes the importance of personal awareness that our actions often have unforeseeable consequences on nature. Organizations like “Recycling Green Team” serve to promote the proper disposal of plastic cups and other recyclable objects at sports events. (NRDC, 2014) Individual efforts and the acceptance of accountability has shown significant improvement in the amount plastic being recycled. However, more is required, as in 2010 41% of the waste collected from the Douglas County landfill could have been recycled instead. (Sierra Club, 2017) Humans undeniably cause damage to nature, yet our current preservation and understanding of our involvement highlights the importance of sustainability in the survival of the human race.

Consumer plastic has left an immense footprint upon the foundation of the local and global environment. It has negatively impacted the environment through factory emissions, pollution of oceans, and longevity within landfills. This problem persists today, even with stronger recycling efforts in place. The overproduction of plastics, such as our College World Series collectible cup, is a byproduct of our consumerist society. Though there are many costs associated with the production, distribution, and waste of plastic, there have also been great societal benefits as well. The advancement of humanity’s technological and scientific development has helped countless lives across the world. When used with intention, plastic may help reduce waste created and slow the progression of human induced pollution. Awareness is imperative in this potential change.

Plastic is a polymer; a substance made up of repeating chemical units. As explained by Andrea Sella, a professor at University College London, “you take a simple organic molecule react it with yourself again and again and again, a little bit like a bicycle chain; you attach one link, and you click on the next one and the next one… almost ad infinitum.” (Knight, 2014) Plastics were not the first manufactured polymer, though. While looking for a cheap substitute for ivory for use in billiards balls, John Wesley Hyatt created the first synthetic polymer in 1869. This scientific innovation was the first of its kind, and importantly did not require the contribution of the products directly extracted from natural resources. (SHI, 2016) Humans now had the complete control of the process for the production of plastic polymers.

Hyatt’s substance was an early predecessor today’s durable plastic. The more immediate precursors to modern-day plastics were substances retrospectively known as “proto-plastics”, such as vulcanized rubber produced in the mid-19th century. (Fenichell, 1996) During World War II, shortages in rubber, brass and aluminum incentivized the substitution of plastic, which became favored following the war for many of its newfound uses. Plastic production expanded exponentially during and after the war. (Meikle, 1995) During WWII, production of synthetic plastic within the United States of America increased by 300%. (SHI, 2016) Due to its immense popularity and economic potential, companies began investing in plastic research to produce new types of plastics “for their own sake and worried about finding uses for them later.” (SHI, 2016) The consumerist vision of plastic had begun.

Innovations of plastics have drastically changed its properties. Modern plastics are now heat resistant, elastic, and can avoid scratches and cracking. These new updates add unknown chemicals to the polymerization process. New societal fears about potential toxicity and easy disposability of plastics have begun to turn plastics use into a cultural and environmental question. (Mossman, 2008) Plastic’s main ingredient is one of the most precious materials on earth: oil. This sought after commodity price has fluctuated greatly through the years, and has affected the progression of plastic research and societal acceptance. (Swallow, 1951)

Plastic “combines the ultimate twentieth-century characteristics - artificiality, disposability, and synthesis - all rolled into one.” (Mossman, 2008) American society now has unlimited access to plastic goods ranging from hula-hoops to lawn furniture. Susan Frienkel describes the United States’ obsession with plastic simply. “In product after product, market after market, plastics challenged traditional materials and won, taking the place of steel in cars, paper and glass in packaging, and wood in furniture.” (Freinkel, 2011) Americans integrated plastic into nearly every aspect of their lives and it is now one of the primary materials in American everyday life.

The industrial and consumer growth has had profound environmental implications. Environmentalists describe plastic as “one of the most ubiquitous and long lasting recent changes to the surface of our planet.” (Fischer, 2017) The explosion of plastics usage has largely paralleled the exponential growth referred to by Anthropocene scholars as the Great Acceleration. Plastic became common in the 1940s, and its use has increased exponentially ever since. The amount of plastic created in the first ten years of this century is greater than the amount produced in the prior century. (Fischer, 2017) Additionally, numbers skyrocketed between the 20th and 21st centuries. In 2007, 230 million tons of plastic were produced globally. (Mossman, 2008) Consumer demand propelled its production and disposal of this product into a great hindrance upon the global environment.

Plastic’s effect upon the earth system is unprecedented. While people can theoretically reuse it, most plastics are created for single-use product, such as disposable water bottles. This has led to incredible amounts of plastics in landfills and the oceans which will remain there unless otherwise removed by humans. Plastics debris found in oceans has rattled the complete acceptance of plastic within American culture. (Meikle, 1997) Plastic objects are held as having three different ends; recycling or reprocessing, thermal destruction which is often done without energy recovery, or disposal in either “a managed system, such as sanitary landfills, or uncontained in open dumps or in the natural environment.” (Geyer, Jambek and Law, 2017)

The image of sea life trapped in plastic has achieved iconic status in environmental critiques of consumerism. Additionally, the negative impact of plastics upon the ocean is not limit to its solidified state. Oil, the primary ingredient of plastic, is always a danger to spilling within some of the world’s major bodies of water. This impending risk has become a reality on numerous occasions, hindering and destroying oceanic life as society knows it.

Furthermore, scientists have discovered that chemicals used in plastics production are detrimental to humans when absorbed, often through consumption of foods and beverages in plastic packaging. (Fischer, 2017) Some of the commonly used chemicals are hazardous due to their toxicity, sensitization, ability to corrode the skin and eyes, carcinogenicity, mutagenicity, and teratogenicity. (Wiberg, 1976) All organisms are susceptible to these effect, not just humans. Due to the great penetration of plastics into everyday life of humankind plastics are a negative component of the everyday life of oceanic, avian, and terrestrial animals. (Wallace, 2016) Due to its shear longevity, the negative implications of plastics within the earth system is significant and perpetual.

On the other hand, plastic does have many benefits. According to the American Chemistry Council, which is admittedly the research arm of the plastics industry, it is beneficial to the environment. Its high strength-weight ratio allows for lighter packaging, resulting lower fuel usage during transportation of products. It takes two pounds of plastic to create an 8 gallon container. The same container would require three pounds of aluminum, eight pounds of steel, or 27 pounds of glass. (ACC, 2018) Plastic products can often reused, recycled, or reimagined as containers, rug fibers, composite lumber, or new pipe products. (EPA, 2016) Plastics-to-oil, or PTO, production is a process which has recently begun gaining traction as a way to gain use from plastic in situations where it is not feasible to recycle plastics. PTO facilities first heat plastic to a gaseous state and then distill the gas into liquid fuel for sale or further refinement. (ACC, 2014) Researchers who represent the plastics lobby believe PTO facilities could divert 20% of the 32.5 million tons of plastic that enter US landfills each year and turn it into fuel.

Plastic is often superior to its substitutes due to superior efficiency, both in terms of money and energy. While plastic began to be widely during WWII due to shortages in other materials, its use continued postwar because for many uses it was cheaper than the original materials. (Meikle, 1995) Plastic use lowers costs for distributors and retailers, thereby lowering the cost of goods packaged in it. (Belasco and Bronner, 2017) A 2010 study conducted by Plastics Europe, a research arm of a plastics lobby, found that the “substitution of plastic products by other materials wherever possible would need about 57% more energy than currently used in the total life cycle of all plastic products today”- the same amount of energy carried by approximately 205 oil tankers. That action would increase would increase annual greenhouse gas emissions by 124 megatons- about the same as Belgium’s total CO₂ emissions in 2000. This is because plastics are less costly to produce and use in terms of energy used. Only 18% of plastic’s energy demand is linked to the period of time the product is being used for its intended purpose relative to an average of 24% for other materials, largely because of its weight savings in packaging and the resulting lowered transportation energy costs. (Denkstatt GmbH, 2010) This is because of plastic’s relatively high strength to weight ratio not found in other common packaging materials. (Andrady and Neal, 2009) These numbers are easily demonstrated in the figure “Life Cycle Energy Consumption of Plastic Products and Their Potential Substitutes” found in the Figure 2. It was estimated that the emissions savings of using plastic products in 2007 rather than its substitutes were 5-9 times the emissions used to produce and dispose of plastic. Furthermore, the negative environmental effects of plastics have often been greatly exaggerated; only 1.3% of an average person’s carbon footprint comes from plastic products whereas recreation and leisure accounts for the largest share of the carbon footprint at 18%. (Andrady and Neal, 2009) It is worth noting again that pretty much all benefits research is done on the behalf of plastics lobbies.

One might ponder the significance of plastic cup in a history museum, as one should. Could it be the familiarity of the object that makes you question its importance? For most people, a common plastic cup from the 1988 College World Series may not reveal much history. In fact, the true historical value of theses cups is surprisingly within the plastic of which it was made. It’s undeniable that humans see and use plastics in almost every aspect of our lives yet the importance of plastic is often overlooked because of its commonality. Moreover, the history of plastic illustrates an ongoing, interconnected relationship between humans, objects, and nature. In fact, Omaha is a great example of this interconnected relationship as it harks back to when railways were used as means for transporting goods and commodities between the east and west. Think about where this plastic originated (St. Louis, Missouri), how it was made, how was it brought to Omaha, what resources were needed to make it, how it was disposed, and how has nature become affected as a result. Plastic has evolved throughout history in order to better benefit human use. However, it is important to understand that with all benefits come costs. This cup emphasizes the importance of personal awareness that our actions often have unforeseeable consequences on nature. Organizations like “Recycling Green Team” serve to promote the proper disposal of plastic cups and other recyclable objects at sports events. (NRDC, 2014) Individual efforts and the acceptance of accountability has shown significant improvement in the amount plastic being recycled. However, more is required, as in 2010 41% of the waste collected from the Douglas County landfill could have been recycled instead. (Sierra Club, 2017) Humans undeniably cause damage to nature, yet our current preservation and understanding of our involvement highlights the importance of sustainability in the survival of the human race.

Consumer plastic has left an immense footprint upon the foundation of the local and global environment. It has negatively impacted the environment through factory emissions, pollution of oceans, and longevity within landfills. This problem persists today, even with stronger recycling efforts in place. The overproduction of plastics, such as our College World Series collectible cup, is a byproduct of our consumerist society. Though there are many costs associated with the production, distribution, and waste of plastic, there have also been great societal benefits as well. The advancement of humanity’s technological and scientific development has helped countless lives across the world. When used with intention, plastic may help reduce waste created and slow the progression of human induced pollution. Awareness is imperative in this potential change.

Creator

Emily Newcomb

Duncan Riley

Craig Schmerbach

Duncan Riley

Craig Schmerbach

Source

American Chemistry Council. Economic Impact of Plastics-To-Oil Facilities in the US. (American Chemistry Council, Oct. 2014). Accessed February 27, 2018. plastics.americanchemistry.com/Product-Groups-and-Stats/Plastics-to-Fuel/Economic-Impact-of-Plastics-to-Oil-Facilities-in-the-United-States-Full-Study.pdf.

Andrady, Anthony L., and Mike A. Neal. “Applications and Societal Benefits of Plastics.” Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences 364, no 1526 (2009): 1977-1984. Accessed February 27, 2018.

Belasco, Warren J. and Simon J. Bronner, ed. “Foodways.” Encyclopedia of American Studies, (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017). Accessed February 27, 2018.

The Cavanaugh Law Firm, P.C., L.L.O. “Omaha Metropolitan Area Solid Waste Management Study.” The Nebraska Sierra Club. Last modified March 13, 2017. Accessed February 6, 2018.https://www.sierraclub.org/sites/www.sierraclub.org/files/sce-authors/u2978/Sierra%20Club%27s%20%20Omaha%20Metropolitan%20Area%20SWM%20Study%20%20March%2013%20%202017.pdf

“Concessions > Reusable Bags and Cups.” National Resources Defence Council, (2014). Accessed March 26, 2018.

Denkstatt GmbH. “The Impact of Plastics on Life Cycle Energy Consumption and Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Europe.” Vienna, Austria. June 2010.

Edwards, Bryant. Process and Apparatus For Forming Plastic Cups or the Like. (Nov. 1965).

Fenichell, Stephen. Plastic: The Making of a Synthetic Century. (HarperCollins., 1996).

Fischer, Douglas. “The Environmental Toll of Plastics.” Environmental Health News. Last modified October 26, 2017. Accessed February 6, 2018. http://www.ehn.org/plastic-environmental-impact-2501923191.html

Freinkel, Susan. Plastic: A Toxic Love Story. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2011.

Geyer, Roland, Jenna R. Jambeck, and Kara Lavender Law. "Production, Use, and Fate of All Plastics Ever Made." Science Advances3, no. 7 (2017). doi:10.1126/sciadv.1700782. "How Our Trash Affects the Whole Planet." Green Living Ideas. March 24, 2016. Accessed May 04, 2018. https://greenlivingideas.com/2015/04/24/how-our-trash-affects-the-whole-planet/.

Knight, Laurence. “A Brief History of Plastics, Natural and Synthetic.” BBC News, BBC, 17 May 2014, www.bbc.com/news/magazine-27442625.

Meikle, Jeffrey L. American Plastic: A Cultural History (Rutgers Univ. Press: 1995). Accessed February 27, 2018.

Meikle, Jeffrey L. "Material Doubts: The Consequences of Plastic." Environmental History 2, no. 3 (1997): 278-300. Accessed February 27, 2018.

Mossman, Susan, Fantastic Plastic: Product Design + Consumer Culture (Black Dog Publishing: 2008). Accessed February 27, 2018.

NRDC. “Guide to Recycling Green Teams at Sports Venues.” National Resources Defense Council, July 2014.

“Plastics: Plastics in Packaging and Consumer Products.” American Chemistry Council. Accessed February 6, 2018. https://plastics.americanchemistry.com/Plastics-in-Packaging-and-Consumer-Products/

Regan, Jennifer, Allen Hershkowitz, Darby Hoover, Alice Henly, and James Hands. “Guide to Recycling Green Teams at Sports Venues: A Roadmap to Help Sports Teams and Venues Develop a Successful Recycling Green Team.” National Resources Defence Council, (2014). Accessed March 26, 2018.

Science History Institute. “The History and Future of Plastics.” Science History Institute, (Dec. 2016). Accessed February 27, 2018.

Swallow, J. C. "The Plastics Industry." Journal of the Royal Society of Arts 99, no. 4843 (1951): 335-81.

United States, Congress, EPA. “2016 Recycling Economic Impact Report.” 2016 Recycling Economic Impact Report (Oct. 2016). Accessed February 27, 2018.

Wallace, Molly, ed. “Letting plastic have its say; or, Plastic’s tell.” Risk criticism (University of Michigan Press, 2016): 123-153. Accessed February 27, 2018.

Wiberg, G. S. “Consumer Hazards of Plastics.” Environmental Health Perspectives 17 (1976): 221-225. Accessed February 27, 2018.

Andrady, Anthony L., and Mike A. Neal. “Applications and Societal Benefits of Plastics.” Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences 364, no 1526 (2009): 1977-1984. Accessed February 27, 2018.

Belasco, Warren J. and Simon J. Bronner, ed. “Foodways.” Encyclopedia of American Studies, (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017). Accessed February 27, 2018.

The Cavanaugh Law Firm, P.C., L.L.O. “Omaha Metropolitan Area Solid Waste Management Study.” The Nebraska Sierra Club. Last modified March 13, 2017. Accessed February 6, 2018.https://www.sierraclub.org/sites/www.sierraclub.org/files/sce-authors/u2978/Sierra%20Club%27s%20%20Omaha%20Metropolitan%20Area%20SWM%20Study%20%20March%2013%20%202017.pdf

“Concessions > Reusable Bags and Cups.” National Resources Defence Council, (2014). Accessed March 26, 2018.

Denkstatt GmbH. “The Impact of Plastics on Life Cycle Energy Consumption and Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Europe.” Vienna, Austria. June 2010.

Edwards, Bryant. Process and Apparatus For Forming Plastic Cups or the Like. (Nov. 1965).

Fenichell, Stephen. Plastic: The Making of a Synthetic Century. (HarperCollins., 1996).

Fischer, Douglas. “The Environmental Toll of Plastics.” Environmental Health News. Last modified October 26, 2017. Accessed February 6, 2018. http://www.ehn.org/plastic-environmental-impact-2501923191.html

Freinkel, Susan. Plastic: A Toxic Love Story. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2011.

Geyer, Roland, Jenna R. Jambeck, and Kara Lavender Law. "Production, Use, and Fate of All Plastics Ever Made." Science Advances3, no. 7 (2017). doi:10.1126/sciadv.1700782. "How Our Trash Affects the Whole Planet." Green Living Ideas. March 24, 2016. Accessed May 04, 2018. https://greenlivingideas.com/2015/04/24/how-our-trash-affects-the-whole-planet/.

Knight, Laurence. “A Brief History of Plastics, Natural and Synthetic.” BBC News, BBC, 17 May 2014, www.bbc.com/news/magazine-27442625.

Meikle, Jeffrey L. American Plastic: A Cultural History (Rutgers Univ. Press: 1995). Accessed February 27, 2018.

Meikle, Jeffrey L. "Material Doubts: The Consequences of Plastic." Environmental History 2, no. 3 (1997): 278-300. Accessed February 27, 2018.

Mossman, Susan, Fantastic Plastic: Product Design + Consumer Culture (Black Dog Publishing: 2008). Accessed February 27, 2018.

NRDC. “Guide to Recycling Green Teams at Sports Venues.” National Resources Defense Council, July 2014.

“Plastics: Plastics in Packaging and Consumer Products.” American Chemistry Council. Accessed February 6, 2018. https://plastics.americanchemistry.com/Plastics-in-Packaging-and-Consumer-Products/

Regan, Jennifer, Allen Hershkowitz, Darby Hoover, Alice Henly, and James Hands. “Guide to Recycling Green Teams at Sports Venues: A Roadmap to Help Sports Teams and Venues Develop a Successful Recycling Green Team.” National Resources Defence Council, (2014). Accessed March 26, 2018.

Science History Institute. “The History and Future of Plastics.” Science History Institute, (Dec. 2016). Accessed February 27, 2018.

Swallow, J. C. "The Plastics Industry." Journal of the Royal Society of Arts 99, no. 4843 (1951): 335-81.

United States, Congress, EPA. “2016 Recycling Economic Impact Report.” 2016 Recycling Economic Impact Report (Oct. 2016). Accessed February 27, 2018.

Wallace, Molly, ed. “Letting plastic have its say; or, Plastic’s tell.” Risk criticism (University of Michigan Press, 2016): 123-153. Accessed February 27, 2018.

Wiberg, G. S. “Consumer Hazards of Plastics.” Environmental Health Perspectives 17 (1976): 221-225. Accessed February 27, 2018.

Collection

Citation

Emily Newcomb

Duncan Riley

Craig Schmerbach, “Plastic Cup,” Omaha in the Anthropocene, accessed April 19, 2024, https://steppingintothemap.com/anthropocene/items/show/18.

Embed

Copy the code below into your web page