Yoke

Title

Yoke

Subject

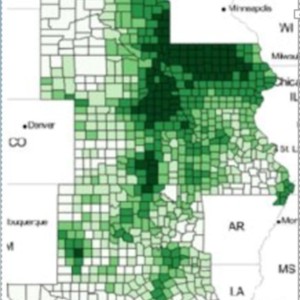

The Great Plains region was unusable for Euro-American farmers without plows and yokes. Yoked oxen pulled steel plows across the prairie, breaking through the tough sod. Yokes like this, usually made out of hardwood, harness the power of oxen. Between the years of 1880-1940 there was a drastic increase of up to 70% in plowed land through the region. Plowed soil was more likely to lose nutrients and become eroded than prairie soil. During the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, the soil turned to black clouds in the wind, furthering erosion. Farming practices have evolved, but grasslands remain under pressure globally. This is one component of the discussion of a new possible era called the Anthropocene.

Description

“In the 1870s the “boomers” were joined by others with excellent reputations as scientists who proclaimed that plowing up the plains had the effect of increasing rainfall - that rain follows the plow.” (Luebke, 2005) This was the mindset that lead to the settling and plowing of the Great Plains. Over several decades, the region was drastically changed through sodbusting and the long-term effects involved. In this region there was a period of major expansion followed by a period of reduction once farmers realized their error. (Cunfer, 2005) These regional changes are one of many as a result of humans occurring in different places globally. A new era for the planet caused by these human interactions, the Anthropocene, might be at hand do to these global environmental changes.

The ox yoke is a tool from ancient times. It is thought they were first used in southern Europe and western Asia. However, it is difficult to determine when and where since the wood they are made of decomposes. But remains of ox horns found in 2900-2600 BCE show indentions thought to be from being tied to a yoke. (Milisauaskas, Sarunus, and Kruk, 1991) A yoke is a wooden bar or frame by which oxen are joined at the heads or necks for accomplishing tasks such as pulling a plow or a wagon.

At first, farming was done largely by hand with few specific tools, later advancements made the job easier and more productive. These new farming techniques were not instantly accepted by people around the globe when they first came to be. Field peasants were weary of these new techniques and were slow to adapt to their changing environments. (Moon, 2013) These people had their ways of cultivating land that was passed on through new generations. Over time though these methods weren’t as efficient due to population growth in a changing world. Other places such as the Great Plains in North America, adapted quickly to use the new technology of oxen and plows to cultivate land.

First, however, the farmer needed a yoke. The pioneers on the upper plains “had to ‘make everything and had to be as ingenious as shipwrecked soldiers.’" (Nadir, 2015) Because trees were so scarce on the Great Plains, the wood used for yokes, fences, houses, and fuel was practically worth more than a life. Everett Dick, a 19th century Nebraska farmer, stated:

In those gun-toting days in Nebraska, if you had something against your neighbor, it was safer to whip out your gun and shoot him than to cut down his trees… Often a killer got away scot-free; but no such subterfuge could be claimed by a tree mutilator. It was the penitentiary for him..." (Dick 1975)

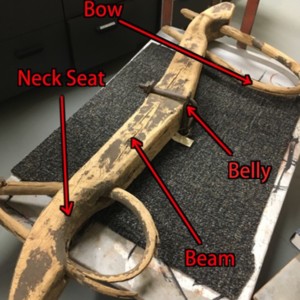

The ox yoke on display at the Durham museum is a handmade neck yoke. We suspect it was made around 1880-1900 out of a hardwood. The neck yoke is most popularly used in the United States for several reasons. Neck yokes offer a few advantages such as comfort for the animal on uneven terrain, maneuverability, and are not custom fitted allowing for use on different oxen. Neck yokes are relatively easy to make even for someone new to woodworking, and safer to use for a novice at working with cattle. (Rapp, 2015) An important factor in why the neck yoke was used in the states was they were traditionally used in England, therefore culturally implemented by settlers and their descendants. (Conroy)

Yokes have been made with wood, as well as with metal, or a combination of the two. (Rapp, 2015) Three different types of yoke are commonly used with oxen today: the head yoke, the neck yoke, and the withers yoke. Head yokes are custom fitted to the horns of a single animal. Neck yokes are attached around the neck of an oxen, where they push with their neck, chest and shoulders. Withers yokes are attached on the shoulder ridge and so, are commonly used on cattle breeds with humps.

The versatility of oxen expands that of simply pulling a cart or plow. Oxen have also been used in the timber industry by being “the ones who skidded [pulled] the fallen trees from the forest”, a job that was dependent on these oxen. (Hribal, 2003) Historically oxen have been used for labor and agriculture over other animals like horses for several reasons. First, oxen are simply cheaper to purchase and easier to maintain. A wooden yoke could also be purchased at a relatively inexpensive price. (Dick, 1975) Oxen also provide better quality manure to fertilize the fields than other farm animals. “He [the ox] not only pulled the plow, harrowed the fields, threshed the grain, and perhaps hauled some of it to the market," the farmer John Moore noted, "all the while providing the manure for the next year’s crop.”

The lack of wood meant that yokes from the early years of farming were often manufactured with other farm equipment and brought to the Great Plains, which then became invaluable to the farmers who began to sodbust the plains. Plowing through unbroken prairie could take years if done alone, even longer and more difficult to do without a team of oxen. Yoked oxen were critical for the early pioneers of the Midwest. With the introduction of the yoke to this region people were finally able to make use of the land for farming by breaking through the hard sod. “Breaking prairie sod required a plow weighing [at least] 30 to 50 kg, typically powered by six to eight oxen” and up to 14 oxen were used to sod-bust across the plains. (Rhoads, 2016) According to an Omaha World Herald article written in 1929, one farmer kept his ox team in use till “more than a thousand acres of land were broken,” when the farmer “sold the two oxen…in 1883 and the yoke was stored away.” (OWH, 1929) This is a great example of how important yokes and oxen were to farmers and how they were kept for as long as possible.

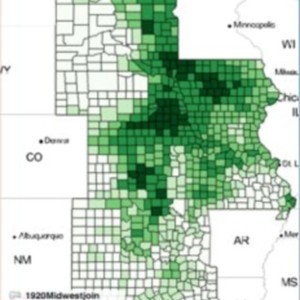

Farming communities like those surrounding Omaha in the upper Midwest were products of plowing. Prior to the introduction of the plow and the oxen that pulled it, the landscape, according to William Heat-Moon in PrairyErth was “eternal prairie and grass, with occasional groups of trees.” (Heat-Moon, 2001) Pioneers did not have the strength to clear the land on their own. Sod is the tough soil of the Great Plains, it is typically covered in tall grass and was often hard enough that houses could be built out of it. The earliest communities on the Great Plains were the Native Americans who roamed the grasslands in search of food and shelter, they were followed in the early-to-mid 1800s by American settlers and explorers. These new people brought modern farming and work animals to the Great Plains. It was only with the integration of working animals before land was of any use to permanent settlements for farming. Oxen were best suited to handle the rolling landscape and thick prairie grass, the yoke and plow were necessary to make the plains yield to European agriculture. As the maps in the appendix show, there was a dramatic change as a result of the yoked oxen being introduced to the Great Plains. The hardships of the plains made the yoke and plow necessary, and through the hard work of yoked oxen teams, both the plains and the quality of life on them had changed forever.

These changes were not just physical to the environment but there were also notable changes to social status of humans as well. Once farmers were able to cultivate the prairie lands it became a massive place for agriculture to occur. “Larger landowners sometimes negotiated a formal contract with sodbusters” to break up the land for them and were in turn paid for their services. (Schob, 1973) This was due to the population of people in the plains becoming so large that people could sell work to landowners who then wouldn’t have to do the hard work of sod-busting on their own farms. All of this changed once the severe environmental impacts made themselves known.

Due to the sod-busting that occurred, followed by the cultivation of never-seen-before crops like corn in this region, the Great Plains changed drastically. (Wishart, 2018) There are very few places, if any, today that would look like they did before this sod-busting occurred. There was suddenly new species of plants and animals to compete for the soil and water that native species had had access to. This competition led to the further depletion of topsoil and nutrients as farmers continued to plow more land. Sod busting did more than allow new species into the area, "sod busting, wind and drought combined to strip away friable soils." (Landa and Feller, 2010) With these factors draining soil of its nutrients, more land was needed to be plowed in order for farmers to maintain the amount harvested.

The cycle of over plowing and planting worsened the Dust Bowl in the 1930s. This was a period of severe dust storms that greatly damaged the ecology and the ability for agriculture of the American prairie. "A widely respected authority on world food problems, George Borgstrom, has ranked the creation of the Dust Bowl as one of the three worst ecological blunders in history." (Worster, 1979) During the drought of the 1930s, topsoil was no longer anchored by the roots of prairie grass turned to dust. This dust was then blown away into huge, blackening clouds by prevailing winds. Droughts had happened before but there had always been prairie grass to hold moisture and soil, now there was nothing to stop the black clouds from covering the plains. This period of drought and major erosion was not exclusively caused by sodbusting but may have been less severe without farmers doing this to the land.

After the Dust Bowl period farmers realized that they surpassed the limits of the land that something needed to change in the Great Plains region. “The true period of adaptation was in the transition era, between about 1930 and 1940, when farmers first reached the natural limits of environment, passed them, and were pulled back by nature.” (Cunfer, 2005) This quote from On the Great Plains summarizes how resilient nature is in its ability to recover after such vast ecological damage has occurred. This transition was not originally a choice of farmers but rather it was natures way of showing how its limits had been surpassed.

Devastating impacts to the Earth, as seen in the Great Plains with Dust Bowl, are not exclusive to this region. There have been major environmental changes to the globe all caused by humans. These impacts have lead some people to think that it should be deemed the start of a new epoch called the Anthropocene. Human impacts have had on the environment globally is without a doubt drastic. “Through harvesting, deforestation, and conversion of grasslands and wetlands, humans have reduced the stock of global terrestrial plant mass by as much as 45% in the last 2000 years.” (Goudie, 2018) This destruction has exponentially increased over time with the different advancements made.

Even today oxen are still widely used. In 1890, there were 1,117,494 oxen reported in the United States census. (Moore, 1961) Even today, there are hundreds of millions of oxen still used on small scale farms. The reasoning for using oxen on many of these small-scale farms is strikingly similar to the past reasoning; it is simply cheaper. Oxen are no longer compared to other working animals, but rather to machinery. Buying a tractor new would be significantly more expensive than buying claves. However, calves require much time, work, and training before they are ready to be yoked for plowing a field. A better comparison might be that of a tractor, costing $15,000, versus a team of grown and well-trained oxen, costing about $1,000 to $2,500. (Collins, 2013) This is still significantly lower in cost than a new tractor which would also require an input of gasoline, maintenance, and other issues that may arise. Oxen on the other hand, will eat the grass where they are kept and provide valuable fertilizer and even after death they have some value in being eaten as meat. (DMO, 2011)

Humans have impacted the environment since the introduction of fire. Taking the once endless expanse of tall grass and adjusting the land for Euro-American farming practices, the plains were changed forever with the use of the ox yoke. Just as cultivated land in the Great Plains drastically increased in the 1900’s, human impacts on the environment globally have greatly increased over time. There have been negative impacts followed with periods of recovery for the Great Plains. This is also seen in other regions of the globe where humans have populated the land but with more devastation than recovery. Since the birth of the human race, devastating changes have been made all over the globe; are these impacts enough to constitute a new era, the Anthropocene?

The ox yoke is a tool from ancient times. It is thought they were first used in southern Europe and western Asia. However, it is difficult to determine when and where since the wood they are made of decomposes. But remains of ox horns found in 2900-2600 BCE show indentions thought to be from being tied to a yoke. (Milisauaskas, Sarunus, and Kruk, 1991) A yoke is a wooden bar or frame by which oxen are joined at the heads or necks for accomplishing tasks such as pulling a plow or a wagon.

At first, farming was done largely by hand with few specific tools, later advancements made the job easier and more productive. These new farming techniques were not instantly accepted by people around the globe when they first came to be. Field peasants were weary of these new techniques and were slow to adapt to their changing environments. (Moon, 2013) These people had their ways of cultivating land that was passed on through new generations. Over time though these methods weren’t as efficient due to population growth in a changing world. Other places such as the Great Plains in North America, adapted quickly to use the new technology of oxen and plows to cultivate land.

First, however, the farmer needed a yoke. The pioneers on the upper plains “had to ‘make everything and had to be as ingenious as shipwrecked soldiers.’" (Nadir, 2015) Because trees were so scarce on the Great Plains, the wood used for yokes, fences, houses, and fuel was practically worth more than a life. Everett Dick, a 19th century Nebraska farmer, stated:

In those gun-toting days in Nebraska, if you had something against your neighbor, it was safer to whip out your gun and shoot him than to cut down his trees… Often a killer got away scot-free; but no such subterfuge could be claimed by a tree mutilator. It was the penitentiary for him..." (Dick 1975)

The ox yoke on display at the Durham museum is a handmade neck yoke. We suspect it was made around 1880-1900 out of a hardwood. The neck yoke is most popularly used in the United States for several reasons. Neck yokes offer a few advantages such as comfort for the animal on uneven terrain, maneuverability, and are not custom fitted allowing for use on different oxen. Neck yokes are relatively easy to make even for someone new to woodworking, and safer to use for a novice at working with cattle. (Rapp, 2015) An important factor in why the neck yoke was used in the states was they were traditionally used in England, therefore culturally implemented by settlers and their descendants. (Conroy)

Yokes have been made with wood, as well as with metal, or a combination of the two. (Rapp, 2015) Three different types of yoke are commonly used with oxen today: the head yoke, the neck yoke, and the withers yoke. Head yokes are custom fitted to the horns of a single animal. Neck yokes are attached around the neck of an oxen, where they push with their neck, chest and shoulders. Withers yokes are attached on the shoulder ridge and so, are commonly used on cattle breeds with humps.

The versatility of oxen expands that of simply pulling a cart or plow. Oxen have also been used in the timber industry by being “the ones who skidded [pulled] the fallen trees from the forest”, a job that was dependent on these oxen. (Hribal, 2003) Historically oxen have been used for labor and agriculture over other animals like horses for several reasons. First, oxen are simply cheaper to purchase and easier to maintain. A wooden yoke could also be purchased at a relatively inexpensive price. (Dick, 1975) Oxen also provide better quality manure to fertilize the fields than other farm animals. “He [the ox] not only pulled the plow, harrowed the fields, threshed the grain, and perhaps hauled some of it to the market," the farmer John Moore noted, "all the while providing the manure for the next year’s crop.”

The lack of wood meant that yokes from the early years of farming were often manufactured with other farm equipment and brought to the Great Plains, which then became invaluable to the farmers who began to sodbust the plains. Plowing through unbroken prairie could take years if done alone, even longer and more difficult to do without a team of oxen. Yoked oxen were critical for the early pioneers of the Midwest. With the introduction of the yoke to this region people were finally able to make use of the land for farming by breaking through the hard sod. “Breaking prairie sod required a plow weighing [at least] 30 to 50 kg, typically powered by six to eight oxen” and up to 14 oxen were used to sod-bust across the plains. (Rhoads, 2016) According to an Omaha World Herald article written in 1929, one farmer kept his ox team in use till “more than a thousand acres of land were broken,” when the farmer “sold the two oxen…in 1883 and the yoke was stored away.” (OWH, 1929) This is a great example of how important yokes and oxen were to farmers and how they were kept for as long as possible.

Farming communities like those surrounding Omaha in the upper Midwest were products of plowing. Prior to the introduction of the plow and the oxen that pulled it, the landscape, according to William Heat-Moon in PrairyErth was “eternal prairie and grass, with occasional groups of trees.” (Heat-Moon, 2001) Pioneers did not have the strength to clear the land on their own. Sod is the tough soil of the Great Plains, it is typically covered in tall grass and was often hard enough that houses could be built out of it. The earliest communities on the Great Plains were the Native Americans who roamed the grasslands in search of food and shelter, they were followed in the early-to-mid 1800s by American settlers and explorers. These new people brought modern farming and work animals to the Great Plains. It was only with the integration of working animals before land was of any use to permanent settlements for farming. Oxen were best suited to handle the rolling landscape and thick prairie grass, the yoke and plow were necessary to make the plains yield to European agriculture. As the maps in the appendix show, there was a dramatic change as a result of the yoked oxen being introduced to the Great Plains. The hardships of the plains made the yoke and plow necessary, and through the hard work of yoked oxen teams, both the plains and the quality of life on them had changed forever.

These changes were not just physical to the environment but there were also notable changes to social status of humans as well. Once farmers were able to cultivate the prairie lands it became a massive place for agriculture to occur. “Larger landowners sometimes negotiated a formal contract with sodbusters” to break up the land for them and were in turn paid for their services. (Schob, 1973) This was due to the population of people in the plains becoming so large that people could sell work to landowners who then wouldn’t have to do the hard work of sod-busting on their own farms. All of this changed once the severe environmental impacts made themselves known.

Due to the sod-busting that occurred, followed by the cultivation of never-seen-before crops like corn in this region, the Great Plains changed drastically. (Wishart, 2018) There are very few places, if any, today that would look like they did before this sod-busting occurred. There was suddenly new species of plants and animals to compete for the soil and water that native species had had access to. This competition led to the further depletion of topsoil and nutrients as farmers continued to plow more land. Sod busting did more than allow new species into the area, "sod busting, wind and drought combined to strip away friable soils." (Landa and Feller, 2010) With these factors draining soil of its nutrients, more land was needed to be plowed in order for farmers to maintain the amount harvested.

The cycle of over plowing and planting worsened the Dust Bowl in the 1930s. This was a period of severe dust storms that greatly damaged the ecology and the ability for agriculture of the American prairie. "A widely respected authority on world food problems, George Borgstrom, has ranked the creation of the Dust Bowl as one of the three worst ecological blunders in history." (Worster, 1979) During the drought of the 1930s, topsoil was no longer anchored by the roots of prairie grass turned to dust. This dust was then blown away into huge, blackening clouds by prevailing winds. Droughts had happened before but there had always been prairie grass to hold moisture and soil, now there was nothing to stop the black clouds from covering the plains. This period of drought and major erosion was not exclusively caused by sodbusting but may have been less severe without farmers doing this to the land.

After the Dust Bowl period farmers realized that they surpassed the limits of the land that something needed to change in the Great Plains region. “The true period of adaptation was in the transition era, between about 1930 and 1940, when farmers first reached the natural limits of environment, passed them, and were pulled back by nature.” (Cunfer, 2005) This quote from On the Great Plains summarizes how resilient nature is in its ability to recover after such vast ecological damage has occurred. This transition was not originally a choice of farmers but rather it was natures way of showing how its limits had been surpassed.

Devastating impacts to the Earth, as seen in the Great Plains with Dust Bowl, are not exclusive to this region. There have been major environmental changes to the globe all caused by humans. These impacts have lead some people to think that it should be deemed the start of a new epoch called the Anthropocene. Human impacts have had on the environment globally is without a doubt drastic. “Through harvesting, deforestation, and conversion of grasslands and wetlands, humans have reduced the stock of global terrestrial plant mass by as much as 45% in the last 2000 years.” (Goudie, 2018) This destruction has exponentially increased over time with the different advancements made.

Even today oxen are still widely used. In 1890, there were 1,117,494 oxen reported in the United States census. (Moore, 1961) Even today, there are hundreds of millions of oxen still used on small scale farms. The reasoning for using oxen on many of these small-scale farms is strikingly similar to the past reasoning; it is simply cheaper. Oxen are no longer compared to other working animals, but rather to machinery. Buying a tractor new would be significantly more expensive than buying claves. However, calves require much time, work, and training before they are ready to be yoked for plowing a field. A better comparison might be that of a tractor, costing $15,000, versus a team of grown and well-trained oxen, costing about $1,000 to $2,500. (Collins, 2013) This is still significantly lower in cost than a new tractor which would also require an input of gasoline, maintenance, and other issues that may arise. Oxen on the other hand, will eat the grass where they are kept and provide valuable fertilizer and even after death they have some value in being eaten as meat. (DMO, 2011)

Humans have impacted the environment since the introduction of fire. Taking the once endless expanse of tall grass and adjusting the land for Euro-American farming practices, the plains were changed forever with the use of the ox yoke. Just as cultivated land in the Great Plains drastically increased in the 1900’s, human impacts on the environment globally have greatly increased over time. There have been negative impacts followed with periods of recovery for the Great Plains. This is also seen in other regions of the globe where humans have populated the land but with more devastation than recovery. Since the birth of the human race, devastating changes have been made all over the globe; are these impacts enough to constitute a new era, the Anthropocene?

Creator

Jen Luttrell

Abbey Rieber

Nicole Shintani

Abbey Rieber

Nicole Shintani

Source

Collins, Rob. “Small Farming With Oxen - Animals - GRIT Magazine.” Grit, Apr. 2013, https://www.grit.com/farm-and-garden/farming-with-oxen-zm0z13mazgou. Accessed March 25, 2018.

Conroy, Drew. "Ox Yokes: Culture, Comfort and Animal Welfare" (PDF). World Association for Transport Animal Welfare and Studies.

Cunfer, Geoff. On the Great Plains: Agriculture and Environment. College Station: Texas A & M University Press, 2005.

Daily Mail Reporter. “Farmers across America Ditch Tractors for Oxen in Bid to Beat Rising Fuel Prices.” Daily Mail Online, Associated Newspapers, 9 May 2011. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1385193/Take-bull-horns-Farmers-America-trade-tractors-oxen-beat-soaring-fuel-prices.html. Accessed March 24, 2018. 3 May 2011.

Dick, Everett. "Conquering the Great American Desert: Nebraska. Conquering the Great American Desert: Nebraska." Nebraska State Historical Society Publications (1975).

Goudie, Andrew. Human Impact on the Natural Environment: Past, Present and Future. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley, 2018.

Hribal, Jason. ""Animals Are Part of the Working Class": A Challenge to Labor History." Labor History 44.4 (2003): 435-53.

Landa E.R. In a Supporting Role: Soil and the Cinema. In: Landa E., Feller C. (eds) Soil and Culture. Springer, Dordrecht. 2010

Luebke, Frederick C. Nebraska: An Illustrated History. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005.

Milisauskas, Sarunus & Janusz Kruk. “Utilization of cattle for traction during the later Neolithic in Southeastern Poland.” Antiquity, Vol. 65, No. 248. September 1991. pp. 562-566

Moon, David. “The Plough that Broke the Steppes: Agriculture and Environment on Russia's Grasslands, 1700-1914” Oxford University Press. 2013.

Moon, William Least Heat. PrairyErth. Houghton Mifflin, 2001. Accessed March 25, 2018.Moore, John H. “The Ox in the Middle Ages.” Agricultural History, vol. 35, no. 2, 1961, pp. 90–93. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3740550

Nadir, Leila C. "Time Out of Place." Cather Studies.10 (2015): 68-96. Accessed March 25, 2018.

Pullen, Daniel J. "Ox and Plow in the Early Bronze Age Aegean." American Journal of Archaeology 96, no. 1 (1992): 45-54. doi:10.2307/505757.

Rapp, Callene. "The Art of Making an Ox Yoke: Working with Wood Can Be a Challenge, but the Finished Product Is Well worth the Effort." Grit 133, no. 2 (2015): 60.

Rhoads, et al. “Historical Changes in Channel Network Extent and Channel Planform in an Intensively Managed Landscape: Natural versus Human-Induced Effects.” Geomorphology, vol. 252, 2016, pp. 17-31.

Schob, David E. "Sodbusting on the Upper Midwestern Frontier, 1820-1860." Agricultural History 47, no. 1 (1973): 47-56.

"State's Last Ox Yoke." Omaha World Herald, May 26, 1929. Accessed March 16, 2018.

Wishart, David. J. "Encyclopedia of the Great Plains." Encyclopedia of the Great Plains | AGRICULTURE. Accessed April 22, 2018. http://plainshumanities.unl.edu/encyclopedia/doc/egp.ag.001.

Worster, Donald. Dust Bowl: The Southern Plains in the 1930s. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979.

Conroy, Drew. "Ox Yokes: Culture, Comfort and Animal Welfare" (PDF). World Association for Transport Animal Welfare and Studies.

Cunfer, Geoff. On the Great Plains: Agriculture and Environment. College Station: Texas A & M University Press, 2005.

Daily Mail Reporter. “Farmers across America Ditch Tractors for Oxen in Bid to Beat Rising Fuel Prices.” Daily Mail Online, Associated Newspapers, 9 May 2011. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1385193/Take-bull-horns-Farmers-America-trade-tractors-oxen-beat-soaring-fuel-prices.html. Accessed March 24, 2018. 3 May 2011.

Dick, Everett. "Conquering the Great American Desert: Nebraska. Conquering the Great American Desert: Nebraska." Nebraska State Historical Society Publications (1975).

Goudie, Andrew. Human Impact on the Natural Environment: Past, Present and Future. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley, 2018.

Hribal, Jason. ""Animals Are Part of the Working Class": A Challenge to Labor History." Labor History 44.4 (2003): 435-53.

Landa E.R. In a Supporting Role: Soil and the Cinema. In: Landa E., Feller C. (eds) Soil and Culture. Springer, Dordrecht. 2010

Luebke, Frederick C. Nebraska: An Illustrated History. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005.

Milisauskas, Sarunus & Janusz Kruk. “Utilization of cattle for traction during the later Neolithic in Southeastern Poland.” Antiquity, Vol. 65, No. 248. September 1991. pp. 562-566

Moon, David. “The Plough that Broke the Steppes: Agriculture and Environment on Russia's Grasslands, 1700-1914” Oxford University Press. 2013.

Moon, William Least Heat. PrairyErth. Houghton Mifflin, 2001. Accessed March 25, 2018.Moore, John H. “The Ox in the Middle Ages.” Agricultural History, vol. 35, no. 2, 1961, pp. 90–93. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3740550

Nadir, Leila C. "Time Out of Place." Cather Studies.10 (2015): 68-96. Accessed March 25, 2018.

Pullen, Daniel J. "Ox and Plow in the Early Bronze Age Aegean." American Journal of Archaeology 96, no. 1 (1992): 45-54. doi:10.2307/505757.

Rapp, Callene. "The Art of Making an Ox Yoke: Working with Wood Can Be a Challenge, but the Finished Product Is Well worth the Effort." Grit 133, no. 2 (2015): 60.

Rhoads, et al. “Historical Changes in Channel Network Extent and Channel Planform in an Intensively Managed Landscape: Natural versus Human-Induced Effects.” Geomorphology, vol. 252, 2016, pp. 17-31.

Schob, David E. "Sodbusting on the Upper Midwestern Frontier, 1820-1860." Agricultural History 47, no. 1 (1973): 47-56.

"State's Last Ox Yoke." Omaha World Herald, May 26, 1929. Accessed March 16, 2018.

Wishart, David. J. "Encyclopedia of the Great Plains." Encyclopedia of the Great Plains | AGRICULTURE. Accessed April 22, 2018. http://plainshumanities.unl.edu/encyclopedia/doc/egp.ag.001.

Worster, Donald. Dust Bowl: The Southern Plains in the 1930s. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979.

Collection

Citation

Jen Luttrell

Abbey Rieber

Nicole Shintani

, “Yoke,” Omaha in the Anthropocene, accessed April 25, 2024, https://steppingintothemap.com/anthropocene/items/show/19.

Embed

Copy the code below into your web page