Monkey Wrench

Title

Monkey Wrench

Subject

Tools like this twentieth-century monkey wrench tuned machines and shaped environments during the Second Industrial Revolution. Associated with railroading in the nineteenth century, the monkey wrench symbolizes industrial progress. Later in the twentieth century, the monkey wrench became a symbol of environmental resistance to industrial progress. In his novel The Monkey Wrench Gang, Edward Abbey popularized an ideology of direct action against environmental destruction, which later inspired environmental organization such as Earth First! and the Earth Liberation Front. This wave of environmentalism found its way to Omaha and led to the formation of the Quality Environment Council and acts of environmental protest on Creighton University’s campus in the 1970s. The monkey wrench is an important artifact of the Anthropocene, symbolizing both industrialism and environmentalism.

Description

First created in nineteenth-century England, the monkey wrench is an adjustable tool used in many areas of industry to insert screws and fasten materials together (Geesin 2015). As such, the monkey wrench is a symbol of the innovation, industrialization and in the context of the Anthropocene, the humans on the earth system. Ironically, the monkey wrench symbolizes resistance to these changes as well. Since the publication of American author Edward Abbey’s novel, The Monkey Wrench Gang in 1975, the tool has become a symbol of radical environmentalism as well. This is the paradox of the monkey wrench: a tool created for use in industry and the taming of the natural world by mankind, has also become a totem for those who radically oppose the very same industrial advancement. The monkey wrench, thus tells us two contrasting stories of the Anthropocene. The first, industrial progress and the second, questioning and active resistance to that “progress”.

The monkey wrench in the collection of the Durham Museum (Figure 1) bears no distinctive markings or indicators as to when or where it was made. However, it was likely manufactured in the early 20th century due to its similarity to examples from that time (Geesin 2015). Its proximity to Omaha, Nebraska is unsurprising, as similar wrenches were utilized and modified in the Omaha area in the 1920s. The elongated handle and ratchet for size adjustment are common features of period wrenches (Inventions New and Interesting). The development of new and improved versions of the monkey wrench tailored the tool to different areas of industry. By the mid-nineteenth-century, the manufacturing of such wrenches was a thriving and competitive industry on its own (Greeley 1874).

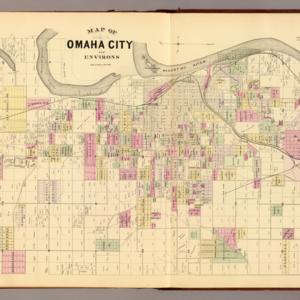

Although different iterations of the monkey wrench were in various areas of industry, one of the most common uses was in the construction and maintenance of steam locomotives. The monkey wrench would have been widely employed in Omaha’s many railroad shops. Omaha was and continues to be the headquarters of the Union Pacific Railroad from the nineteenth-century (Monkey Wrench). Figure 2 is a map of Omaha from 1885 depicting the transformational effect that the Union Pacific railroad imparted on the city after only two decades of prevalence. The pink area on the lower-right portion of the map shows the expanse of the Union Pacific Shops.

The city grew and developed in the nineteenth-century largely as a result of its relationship with the Union Pacific Railroad. After the railroad construction began in the 1860s, an influx of employment opportunities in Omaha allowed for its growth to surpass its neighbor cities and the city became a gateway to the Western portion of the United States. The project of building the railroad brought thousands of jobs to the Omaha area and this opportunity to make a living working on it saw Omaha’s population increase at an incredible rate (Bristow 2000). By the twentieth-century, Omaha had become a railroad hub and central city of the second industrial revolution in the United States.

The growth of Omaha’s railroad industry transformed Omaha and Nebraska with dramatic environmental consequences. In an 1867 book, The Union Pacific Railroad from Omaha, Nebraska, Across the Continent, the Union Pacific Railroad Company outlines the economic opportunities afforded by the construction of the railroad. These opportunities were headlined by the opportunity to expand the areas in which people live westward, bridging the gap between the Eastern and Western United States. In addition, natural resources such as untapped land for farming, mining, hunting and harvesting lumber were held as the most lucrative of opportunities. During this time period, the Union Pacific railroad transported 460,000 tons of freight across the continent each year (The Union Pacific Railroad Company 1867). This industrial expanding of the railroad to the West would manifest itself through an immense impact on the environment of the Great Plains.

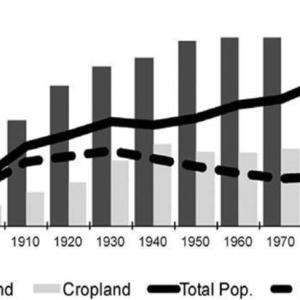

As the railroad stretched West towards the Rocky Mountains, populations and land usage in the Great Plains region increased at an incredible rate. The further that the railroad stretched, the more settlements were established along it. These settlements enabled the land to be used by the new people in an area where it had been nearly impossible to receive supplies and contact with the East prior to railroad construction (Whitney 1994). Figure 3 shows measured usages of land for raising livestock and crops, as well as the population in the Great Plains region after construction on the Transcontinental Railroad from Omaha began. Once a small number of individuals had begun to populate the Great Plains and begin to tame the land, the success of their agricultural endeavors coupled with the ease of communication with the rest of the country established by the railroad and the transcontinental telegraph brought people seeking prosperity in the region (Hartman 2011). As the region was further developed throughout the decades following the establishment of rural communities, the impact of large-scale agriculture took its toll on the local and global environments.

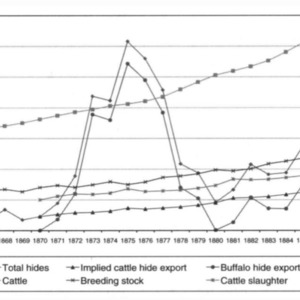

In addition to the establishment of a booming agriculture industry in the Great Plains, the railroad enabled transnational and international trade of hides and furs of animals. One striking example was the systematic destruction and near extinction of the North American Bison. Figure 4 demonstrates the marked spike in the number of bison hide exports almost immediately after the beginning of railroad construction from Omaha, along with the consistent rise in cattle population in the Great Plains (Taylor 2011, Bozell 1995). Bison hide exports declined significantly in the late 1870s as the population of bison dwindled in the region, while the cattle population maintained its steady rise through the late 1880s. The hunting of bison to virtual extinction is an example of the devastating damage that the increased accessibility to the Great Plains established by the railroad had on its environment (Taylor 2011). There is a stark increase and subsequent decrease in the number of bison hides exported as the population dwindled in the 1870s (Hartman 2011).

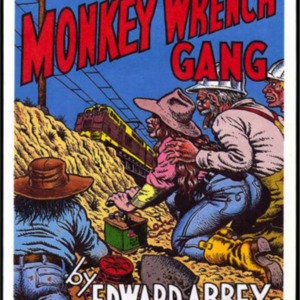

As a tool and symbol of industry, the monkey wrench represented the growth of progress and urbanization and taming of their surrounding landscapes. In Omaha and Nebraska, the railroad played an important role in these changes that also resulted in significant environmental consequences, especially in grassland environments. However, this rampant industrialization was no longer accepted uncritically as “progress” by the mid-twentieth-century. “Monkey Wrenching” came to embody active resistance to industrial growth at the expense of the environment. This term entered public discourse upon publication of Edward Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench Gang in 1975. In his novel Abbey tells the fictional story of a group of activists who commit acts of sabotage in the name of environmentalism. The group destroys bridges, billboards and makes plans to destroy a dam. Their activities, called “monkeywrenching,” lauded the destruction of industrial property for the sake of saving the natural world from development (Abbey 1975). Figure 5 is an example of illustrations by Robert Crumb from The Monkey Wrench Gang. Abbey’s characters saw industry, government-sponsored or corporate, as a threat and promoted uncompromising resistance.

After the release of The Monkey Wrench Gang, the monkey wrench was a widely recognized symbol for radical environmentalism as it had been described in the book. The writing itself became a handbook for those looking to shake up the industrial establishment through acts of monkeywrenching. From the ideology of Edward Abbey sprung a variety of radical environmental groups, most notably the Earth Liberation Front (ELF) and Earth First! of which Abbey was a member. The actions of destroying machines in an attempt to slow the progress of industry harken back to the attempted Luddite revolution in late 18th century England. Although the Luddites were motivated by the prospect of keeping their own jobs in industry, the consequences of destroying machinery were much the same (Horn 2005).

The ideology established by Abbey in the late twentieth-century was one of resistance to industrial development of the environment. This ideology manifested itself in acts of direct and indirect resistance. In the vain of direct resistance, groups such as Earth First! And the ELF, established in 1980 and 1992 respectively, committed acts of sabotage in the United States. Bombings claimed by ELF have targeted ski resorts, animal testing facilities, fishing operations and other sites of humans meddling with the environment. This led to ELF’s listing as the greatest domestic threat in the United States by the FBI in 2001 (Taylor 2008). Earth First! did not claim responsibility for destructive crimes, although some of their members have been personally indicted for various acts of sabotage. In 1983, an editorial in the journal Environmental Ethics personally addressed Edward Abbey and his friends for actively encouraging the destruction of industrial resources, thus endangering the lives of workers. Abbey responded directly, claiming that Earth First! is little more than a disorganized group of environmentalists who come together for acts of civil disobedience in the face of the destruction of nature. He also plainly stated that he believes that the destruction of nature is an act of terrorism (Abbey 1983). Foreman takes matters a step further, openly denying acts of monkeywrenching in Earth First! while directly stating that he believes that such acts are completely morally justified (Foreman 1983).

The direct actions of groups such as Earth First! and ELF coupled with a new ideology of environmentalism had a massive impact on the United States throughout the late 20th century. Other citizens intent on protecting the environment practiced indirect resistance to industrial progress. In Omaha, these effects manifested in the creation of the Quality Environment Council (QEC). Established in the 1970s, the Omaha QEC protected the parks and open spaces in Omaha against development. Its original goal was to prevent the construction of a mall in downtown Omaha. They managed to prevent further development within the city in this case, however this simply diverted the same development to the suburbs (Taylor 1973). The QEC also vehemently opposed the release of extremely hot waste water into the Missouri river by the Omaha Public Power District in 1972. They succeeded in the city imposing a required cooling time for all water being disposed of in the river to prevent destruction of the environment within (Omaha World Herald 1972).

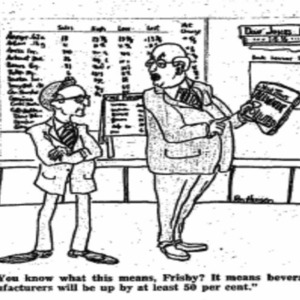

On the campus of Creighton University, students reacted negatively to the environmental policies of the Nixon administration in the 1970s. Although Nixon was the president who established the Environmental Protection Agency, students at Creighton did not believe that this was enough, given the publication of a study claiming that 73% of all water in the United States is contaminated with industrial byproducts. Figure 6 displays a political cartoon published in The Creightonian, the school newspaper. This is an example of civil disobedience within the student population against large companies and government policies. The article published with this cartoon admonishes the industrial domination of nature, providing examples of deforestation, water contamination and animal populations nearing extinction (Meyer 1970). In a further article from The Creightonian, the newspaper announces the beginning of seemingly the first ecology class at the university. With its purpose to study the physical and social implications of the environment and the factors which contribute to damaging it, this certainly shows a shift in the mindset of people in Omaha towards at least some form of environmentalism (Lohr 1972).

The monkey wrench, through its contributions to industry primarily through the railroad, has historically been a tool and symbol of industrial progress. The meaning of progress changed over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth-centuries, however. By the Green Decades of the 1960s and 1970s, and drawing upon criticisms of corporate and state “development,” the monkey wrench became a symbol of resistance. Direct resistance of the type advocated by Edward Abbey and radical groups such as Earth First! and the ELF, though these strategies found little support in Nebraska or Omaha. In Omaha, indirect resistance was the primary mode of fighting industrial progress for the betterment of the natural environment. The dual symbolism of the monkey wrench, promoting progress and simultaneously symbolizing resistance to it, is a fitting artifact of the Anthropocene.

The monkey wrench in the collection of the Durham Museum (Figure 1) bears no distinctive markings or indicators as to when or where it was made. However, it was likely manufactured in the early 20th century due to its similarity to examples from that time (Geesin 2015). Its proximity to Omaha, Nebraska is unsurprising, as similar wrenches were utilized and modified in the Omaha area in the 1920s. The elongated handle and ratchet for size adjustment are common features of period wrenches (Inventions New and Interesting). The development of new and improved versions of the monkey wrench tailored the tool to different areas of industry. By the mid-nineteenth-century, the manufacturing of such wrenches was a thriving and competitive industry on its own (Greeley 1874).

Although different iterations of the monkey wrench were in various areas of industry, one of the most common uses was in the construction and maintenance of steam locomotives. The monkey wrench would have been widely employed in Omaha’s many railroad shops. Omaha was and continues to be the headquarters of the Union Pacific Railroad from the nineteenth-century (Monkey Wrench). Figure 2 is a map of Omaha from 1885 depicting the transformational effect that the Union Pacific railroad imparted on the city after only two decades of prevalence. The pink area on the lower-right portion of the map shows the expanse of the Union Pacific Shops.

The city grew and developed in the nineteenth-century largely as a result of its relationship with the Union Pacific Railroad. After the railroad construction began in the 1860s, an influx of employment opportunities in Omaha allowed for its growth to surpass its neighbor cities and the city became a gateway to the Western portion of the United States. The project of building the railroad brought thousands of jobs to the Omaha area and this opportunity to make a living working on it saw Omaha’s population increase at an incredible rate (Bristow 2000). By the twentieth-century, Omaha had become a railroad hub and central city of the second industrial revolution in the United States.

The growth of Omaha’s railroad industry transformed Omaha and Nebraska with dramatic environmental consequences. In an 1867 book, The Union Pacific Railroad from Omaha, Nebraska, Across the Continent, the Union Pacific Railroad Company outlines the economic opportunities afforded by the construction of the railroad. These opportunities were headlined by the opportunity to expand the areas in which people live westward, bridging the gap between the Eastern and Western United States. In addition, natural resources such as untapped land for farming, mining, hunting and harvesting lumber were held as the most lucrative of opportunities. During this time period, the Union Pacific railroad transported 460,000 tons of freight across the continent each year (The Union Pacific Railroad Company 1867). This industrial expanding of the railroad to the West would manifest itself through an immense impact on the environment of the Great Plains.

As the railroad stretched West towards the Rocky Mountains, populations and land usage in the Great Plains region increased at an incredible rate. The further that the railroad stretched, the more settlements were established along it. These settlements enabled the land to be used by the new people in an area where it had been nearly impossible to receive supplies and contact with the East prior to railroad construction (Whitney 1994). Figure 3 shows measured usages of land for raising livestock and crops, as well as the population in the Great Plains region after construction on the Transcontinental Railroad from Omaha began. Once a small number of individuals had begun to populate the Great Plains and begin to tame the land, the success of their agricultural endeavors coupled with the ease of communication with the rest of the country established by the railroad and the transcontinental telegraph brought people seeking prosperity in the region (Hartman 2011). As the region was further developed throughout the decades following the establishment of rural communities, the impact of large-scale agriculture took its toll on the local and global environments.

In addition to the establishment of a booming agriculture industry in the Great Plains, the railroad enabled transnational and international trade of hides and furs of animals. One striking example was the systematic destruction and near extinction of the North American Bison. Figure 4 demonstrates the marked spike in the number of bison hide exports almost immediately after the beginning of railroad construction from Omaha, along with the consistent rise in cattle population in the Great Plains (Taylor 2011, Bozell 1995). Bison hide exports declined significantly in the late 1870s as the population of bison dwindled in the region, while the cattle population maintained its steady rise through the late 1880s. The hunting of bison to virtual extinction is an example of the devastating damage that the increased accessibility to the Great Plains established by the railroad had on its environment (Taylor 2011). There is a stark increase and subsequent decrease in the number of bison hides exported as the population dwindled in the 1870s (Hartman 2011).

As a tool and symbol of industry, the monkey wrench represented the growth of progress and urbanization and taming of their surrounding landscapes. In Omaha and Nebraska, the railroad played an important role in these changes that also resulted in significant environmental consequences, especially in grassland environments. However, this rampant industrialization was no longer accepted uncritically as “progress” by the mid-twentieth-century. “Monkey Wrenching” came to embody active resistance to industrial growth at the expense of the environment. This term entered public discourse upon publication of Edward Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench Gang in 1975. In his novel Abbey tells the fictional story of a group of activists who commit acts of sabotage in the name of environmentalism. The group destroys bridges, billboards and makes plans to destroy a dam. Their activities, called “monkeywrenching,” lauded the destruction of industrial property for the sake of saving the natural world from development (Abbey 1975). Figure 5 is an example of illustrations by Robert Crumb from The Monkey Wrench Gang. Abbey’s characters saw industry, government-sponsored or corporate, as a threat and promoted uncompromising resistance.

After the release of The Monkey Wrench Gang, the monkey wrench was a widely recognized symbol for radical environmentalism as it had been described in the book. The writing itself became a handbook for those looking to shake up the industrial establishment through acts of monkeywrenching. From the ideology of Edward Abbey sprung a variety of radical environmental groups, most notably the Earth Liberation Front (ELF) and Earth First! of which Abbey was a member. The actions of destroying machines in an attempt to slow the progress of industry harken back to the attempted Luddite revolution in late 18th century England. Although the Luddites were motivated by the prospect of keeping their own jobs in industry, the consequences of destroying machinery were much the same (Horn 2005).

The ideology established by Abbey in the late twentieth-century was one of resistance to industrial development of the environment. This ideology manifested itself in acts of direct and indirect resistance. In the vain of direct resistance, groups such as Earth First! And the ELF, established in 1980 and 1992 respectively, committed acts of sabotage in the United States. Bombings claimed by ELF have targeted ski resorts, animal testing facilities, fishing operations and other sites of humans meddling with the environment. This led to ELF’s listing as the greatest domestic threat in the United States by the FBI in 2001 (Taylor 2008). Earth First! did not claim responsibility for destructive crimes, although some of their members have been personally indicted for various acts of sabotage. In 1983, an editorial in the journal Environmental Ethics personally addressed Edward Abbey and his friends for actively encouraging the destruction of industrial resources, thus endangering the lives of workers. Abbey responded directly, claiming that Earth First! is little more than a disorganized group of environmentalists who come together for acts of civil disobedience in the face of the destruction of nature. He also plainly stated that he believes that the destruction of nature is an act of terrorism (Abbey 1983). Foreman takes matters a step further, openly denying acts of monkeywrenching in Earth First! while directly stating that he believes that such acts are completely morally justified (Foreman 1983).

The direct actions of groups such as Earth First! and ELF coupled with a new ideology of environmentalism had a massive impact on the United States throughout the late 20th century. Other citizens intent on protecting the environment practiced indirect resistance to industrial progress. In Omaha, these effects manifested in the creation of the Quality Environment Council (QEC). Established in the 1970s, the Omaha QEC protected the parks and open spaces in Omaha against development. Its original goal was to prevent the construction of a mall in downtown Omaha. They managed to prevent further development within the city in this case, however this simply diverted the same development to the suburbs (Taylor 1973). The QEC also vehemently opposed the release of extremely hot waste water into the Missouri river by the Omaha Public Power District in 1972. They succeeded in the city imposing a required cooling time for all water being disposed of in the river to prevent destruction of the environment within (Omaha World Herald 1972).

On the campus of Creighton University, students reacted negatively to the environmental policies of the Nixon administration in the 1970s. Although Nixon was the president who established the Environmental Protection Agency, students at Creighton did not believe that this was enough, given the publication of a study claiming that 73% of all water in the United States is contaminated with industrial byproducts. Figure 6 displays a political cartoon published in The Creightonian, the school newspaper. This is an example of civil disobedience within the student population against large companies and government policies. The article published with this cartoon admonishes the industrial domination of nature, providing examples of deforestation, water contamination and animal populations nearing extinction (Meyer 1970). In a further article from The Creightonian, the newspaper announces the beginning of seemingly the first ecology class at the university. With its purpose to study the physical and social implications of the environment and the factors which contribute to damaging it, this certainly shows a shift in the mindset of people in Omaha towards at least some form of environmentalism (Lohr 1972).

The monkey wrench, through its contributions to industry primarily through the railroad, has historically been a tool and symbol of industrial progress. The meaning of progress changed over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth-centuries, however. By the Green Decades of the 1960s and 1970s, and drawing upon criticisms of corporate and state “development,” the monkey wrench became a symbol of resistance. Direct resistance of the type advocated by Edward Abbey and radical groups such as Earth First! and the ELF, though these strategies found little support in Nebraska or Omaha. In Omaha, indirect resistance was the primary mode of fighting industrial progress for the betterment of the natural environment. The dual symbolism of the monkey wrench, promoting progress and simultaneously symbolizing resistance to it, is a fitting artifact of the Anthropocene.

Creator

Brad MacDonald

Hasan Lari

Hasan Lari

Source

Abbey, E. “Earth first! And the Monkey Wrench Gang.” Environmental Ethics 5, no.1 (1983): 94-95. https://www.pdcnet.org//pdc/bvdb.nsf

Abbey, E. The Monkey Wrench Gang (Salt Lake City: Dream Garden Press, 1975).

Bozell, J. “Culture, Environment, and Bison Populations on the Late Prehistoric and Early Historic Central Plains.” Plains Anthropologist. 40, no. 152 (1995): 145-163.

Bristow, D. A Dirty, Wicked Town: Tales of 19th Century Omaha (Omaha: University of Nebraska Press, 2000), 152-154.

Foreman, D. “More on Earth First! And The Monkey Wrench Gang.” Environmental Ethics. 5, no.1 (1983): 95-96.

Geesin, R. Adjustable Spanner: History, Origins and Development to 1970 (Crowood: Antiques & Collectibles, 2015).

George M. Smith, Omaha Central. 1885. Lithographed map, 40 x 69 cm. David Rumsey. From: David Rumsey Historical Map Collection, www.davidrumsey.com (Accessed April 4, 2018).

Greeley, H. The Great Industries of the United States (Hartford: J.B. Burr & Hyde, 1874), 875-876.

Gutmann, M. “Beyond Social Science History: Population and Environment in the US Great Plains.” Social Science History, 42, no. 1 (2018).

Hartman, M. “Impact of Historical Land-Use Changes on Greenhouse Gas Exchange in the U.S. Great Plains, 1883-2003.” Ecological Applications. 21, no. 4 (2011): 1105-1119.

Horn, J. “Machine-breaking in England and France during the Age of Revolution.” Labour 55, (2005): 143-166.

“Hot Water Dumping Is Protested,” The Omaha World Herald (Omaha, NE), July 19, 1972.

"Inventions New and Interesting." Scientific American 127, no. 2 (1922): 117-20. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24993964

Lohr, J. “Ecology Course To Study Physical, Social Environment,” The Creightonian (Omaha, NE), October 27, 1972.

Meyer, M. “Environment: Student Issue,” The Creightonian (Omaha, NE), January 9, 1970.

“Monkey Wrench.” America on the Move, last modified 2018, http://amhistory.si.edu/onthemove/collection/object_137

Crumb, Robert. The Monkey Wrench Gang. 1975. Source: JohnShalek.com, 2009, Digital Image. Available from: http://www.joshshalek.com/tag/the-monkey-wrench-gang/

Taylor, Bron. "The Tributaries of Radical Environmentalism." Journal for the Study of Radicalism 2, no. 1 (2008): 27-61. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41887590.

Taylor, J. “Leahy: River Critics ‘In A Dream World’,” The Omaha World Herald (Omaha, NE), July 25, 1973.

Taylor, S. “International Trade and the Virtual Extinction of the North American Bison.” American Economic Association. 101, no. 7 (2011): 3162-3195.

Union Pacific Railroad Company, The Union Pacific Railroad from Omaha, Nebraska, Across the Continent (Chicago: Press of Wynkoop & Hallenbeck, 1867), 7.

Whitney, G. From Coastal Wilderness to Fruited Plain (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 188-190.

Zalasiewicz, J. “Stratigraphy of the Anthropocene.” Philosophical Transitions. 396 (2016): 1036- 1055.

Abbey, E. The Monkey Wrench Gang (Salt Lake City: Dream Garden Press, 1975).

Bozell, J. “Culture, Environment, and Bison Populations on the Late Prehistoric and Early Historic Central Plains.” Plains Anthropologist. 40, no. 152 (1995): 145-163.

Bristow, D. A Dirty, Wicked Town: Tales of 19th Century Omaha (Omaha: University of Nebraska Press, 2000), 152-154.

Foreman, D. “More on Earth First! And The Monkey Wrench Gang.” Environmental Ethics. 5, no.1 (1983): 95-96.

Geesin, R. Adjustable Spanner: History, Origins and Development to 1970 (Crowood: Antiques & Collectibles, 2015).

George M. Smith, Omaha Central. 1885. Lithographed map, 40 x 69 cm. David Rumsey. From: David Rumsey Historical Map Collection, www.davidrumsey.com (Accessed April 4, 2018).

Greeley, H. The Great Industries of the United States (Hartford: J.B. Burr & Hyde, 1874), 875-876.

Gutmann, M. “Beyond Social Science History: Population and Environment in the US Great Plains.” Social Science History, 42, no. 1 (2018).

Hartman, M. “Impact of Historical Land-Use Changes on Greenhouse Gas Exchange in the U.S. Great Plains, 1883-2003.” Ecological Applications. 21, no. 4 (2011): 1105-1119.

Horn, J. “Machine-breaking in England and France during the Age of Revolution.” Labour 55, (2005): 143-166.

“Hot Water Dumping Is Protested,” The Omaha World Herald (Omaha, NE), July 19, 1972.

"Inventions New and Interesting." Scientific American 127, no. 2 (1922): 117-20. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24993964

Lohr, J. “Ecology Course To Study Physical, Social Environment,” The Creightonian (Omaha, NE), October 27, 1972.

Meyer, M. “Environment: Student Issue,” The Creightonian (Omaha, NE), January 9, 1970.

“Monkey Wrench.” America on the Move, last modified 2018, http://amhistory.si.edu/onthemove/collection/object_137

Crumb, Robert. The Monkey Wrench Gang. 1975. Source: JohnShalek.com, 2009, Digital Image. Available from: http://www.joshshalek.com/tag/the-monkey-wrench-gang/

Taylor, Bron. "The Tributaries of Radical Environmentalism." Journal for the Study of Radicalism 2, no. 1 (2008): 27-61. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41887590.

Taylor, J. “Leahy: River Critics ‘In A Dream World’,” The Omaha World Herald (Omaha, NE), July 25, 1973.

Taylor, S. “International Trade and the Virtual Extinction of the North American Bison.” American Economic Association. 101, no. 7 (2011): 3162-3195.

Union Pacific Railroad Company, The Union Pacific Railroad from Omaha, Nebraska, Across the Continent (Chicago: Press of Wynkoop & Hallenbeck, 1867), 7.

Whitney, G. From Coastal Wilderness to Fruited Plain (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 188-190.

Zalasiewicz, J. “Stratigraphy of the Anthropocene.” Philosophical Transitions. 396 (2016): 1036- 1055.

Collection

Citation

Brad MacDonald

Hasan Lari, “Monkey Wrench,” Omaha in the Anthropocene, accessed April 26, 2024, https://steppingintothemap.com/anthropocene/items/show/23.

Embed

Copy the code below into your web page