Trans-Mississippi Exposition

Title

Trans-Mississippi Exposition

Subject

The Trans-Mississippi Exposition was a World’s Fair hosted in Omaha in 1898. This pamphlet described the attractions and new technological developments on display. Sponsors hoped the fair would boost the local economy and encourage settlement in unclaimed Western lands. People could then use those natural resources as a source for profit. The fair’s fantastic Renaissance-style buildings showed this potential for success, but they only existed for one year. Planners constructed buildings with cheap materials and destroyed them after the fair ended. No buildings from the fair remain today. The fair, and this artifact, are a symbol of this frontier sensibility. People treated the environment in the same way: using resources until they were not profitable, and then moving on. This exploitation of nature for profit is a common theme of the Anthropocene.

Description

“The mighty West affords striking evidences of the splendid achievements and possibilities of our people,” remarked President William McKinley. “It is a matchless tribute to the energy and endurance of the pioneer, while its vast agricultural development, its progress in manufactures, its advancement in the arts and sciences, and in all departments of education and endeavor, have been inestimable contributions to the civilization and wealth of the world.” Few times in the prior history of America did it possess the opportunity to demonstrate its affluence and ingenuity as it did with the platform of World’s Fairs and Expositions in the late 19th century. Catalyzed by the synthesis of resource and resourcefulness, industry elevated America on the new global capitalist stage. Greater than anticipated, the then-untamed West possessed a wealth of resources for cultivation and extraction alike. The success afforded the majority of the nation as a result of its Western backbone led to many celebrations of the West in the form of lavish World’s Fairs, the prime model being Chicago’s Columbian Exposition in 1893. However successful the West had appeared, in truth the West’s ability to support the new industrial America was an illusion. The West’s extreme prosperity came at the cost of an ever-accelerating requirement for a finite amount of new land: over-commodifying the land had exhausted its ability to produce. The same boom and bust mirrored in the years to come in the lesser Western fairs and expositions: demonstrating illusive staying power and affluence, but in truth embodying overexploitation and their promises preying on the hopeful.

The 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition exists as a metaphor for the boom-and-bust nature of capitalism in the developing West. All facets of the exposition illustrated these cyclic patterns, ranging from the physical construction and demolition of the exposition buildings to its impact on the local economy. Boom-and-bust financial cycles were fundamental and recurrent phenomena in capitalist economies in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Since the 1970s, environmental historians have critiqued the predominant economic interpretation of these cycles, emphasizing their connections to western expansion. A “capitalist ethos” reframed nature as resource and incentivized the utilization of Western resource frontiers for financial gain. Omaha’s economic success in the 1890s reflected in the exposition’s ability to market the untamed Western land purely as substances ready for new settlers to exploit. This capitalist ethos originated from the idea that humans are separate from nature, a mindset that resonated throughout the exposition, what Jason Moore refers to as Cartesian dualism that prevails in practice. This rejection of ties with the natural environment enabled drastic overexploitation, without consideration for future viability. The Omaha Trans-Mississippi International Exposition represented the cyclic pattern of success and decline caused by many similar dualisms, evidenced in the exposition’s physical construction as well as its fluctuating economic outcomes.

The Omaha 1898 International Exposition pamphlet (Figure 1) was a commemorative item and a contemporary guide for attendees of the 1898 Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition. It was distributed beginning in June during the 1898 festival and provided 32 pages of detailed exhibit coverage. It supplied visitors with necessary information regarding available amenities and transportation around Omaha, a comprehensive exhibit guide, and details about the available diversions, including carnivalesque swordsmen, mazes, and funhouses. The pamphlet first describes the layout of the exposition as a guide for navigation. The exposition grounds consisted of Renaissance-style buildings surrounding a lagoon (Figure 3). Nearly half the pamphlet consisted of photographs of these architectural installations. The classical, palatial aesthetic of the Omaha Exhibition was proudly lauded, illustrating the grandeur of the fair.

The pamphlet enumerates the exhibits housed within each of the state buildings, as well as exhibits documenting substantial achievements. Specific care is taken describing the special exhibits. The government exhibit (Figure 4) displayed exotic artifacts, such as a draft of the Declaration of Independence, and featured military and educational advancements that promoted imperialist sentiments. The Indian Exhibit, when juxtaposed with the exposition’s impressive shows of classical architecture, technology, and material wealth, emphasized the progress of colonialism. Other major exhibits, such as the Agriculture (Figure 5), Electricity, and Machinery buildings, presented the technological advancements and the resources wrought by these newfound processes in order to glorify the technological progress and economic opportunity in the West.

The Exposition celebrated western technology and colonial progress, and their relationship to economic opportunity, though the fair itself was an opportunity for financial gain. Ironically, this fair celebrating western progress originated when the entire nation was recovering from the Financial Panic of 1893. Western states were disproportionately impacted by the panic and therefore especially determined to revitalize their economic prospects. Several macroeconomic problems initiated the beginning of an economic recession; however, the addition of unexpected Western crop failures pushed a common depression into a financial panic. These agricultural shocks were most prevalent in the Western and North Central states, including Nebraska, which caused bank failures that were strongly concentrated in Western states. National and Eastern banks, which were less influenced by the struggling Western agricultural markets, did not experience the same magnitude of the recession following the panic. However, rural banks depended on the success of nearby farms, so local and state banks in the West failed more frequently than in other regions.

The Trans-Mississippi Exposition was a direct response to this economic disaster. Shortly after the recession, Omaha leaders determined that an exposition would successfully communicate the financial potential of the West to the rest of the nation and perhaps resurrect the economic stability in the region. The immense, unprecedented success of Chicago’s Columbian Exposition in 1893 inspired several Western leaders to advocate similar projects in their respective cities. In 1894, Nebraskan delegates invited the Trans-Mississippi Congress, a group of men from Western states who promoted the commercial and material interests of their region, to host the next annual meeting in Omaha. After proposing the idea to the Congress in 1895, local Omaha businessmen successfully committed their city to host an exposition.

The 1898 Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition, also known as the Omaha World’s Fair, was one of forty international expositions that occurred during the “Golden Age of Fairs” from 1880-1910. The purpose of the Omaha World’s Fair was to exemplify the fertility and potential of Western farming and manufacturing as a definite pathway to financial success. The initial settlers already utilized the Western resources by growing crops and raising livestock, but many were still skeptical about adopting the pioneer lifestyle. The number of Nebraskan farms drastically increased from 1870-1890, but then growth and settlement stagnated through the 1890s following the agricultural failures from Panic of 1893. The development of new procedures and technologies provided a stronger promise of success for those moving West. William Jennings Bryan, the spokesman for the Nebraska committee of the Trans-Mississippi Congress, stated, “We believe that an exposition of all the products, industries and civilization of the States west of the Mississippi River, made at some central gateway where the world can behold the wonderful capabilities of these great wealth-producing States, would be of great value, not only to the Trans-Mississippi States, but to all the homeseekers in the world.” The planners hoped the exposition would directly combat the previous notion of the West as having low and unpredictable crop yields observed in the Panic of 1893. By projecting Western industrial and agricultural success to the rest of the nation, Omaha leaders sought to attract settlers to utilize the abundant resources in order to boost the local economy.

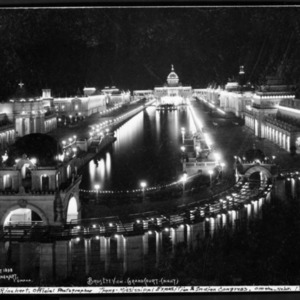

The desire to project an image of the West’s success and appeal to potential settlers influenced the construction of the fairgrounds itself, though its execution occurred in a temporary and superficial manner. The goal of the architecture and landscaping was to produce the impression of a prosperous civilization: full of order and stability. A two-thousand foot-long lagoon designed to resemble Venetian canals hosted gondola rides as a whimsical form of transportation throughout the fair (Figure 6) . Stately trees and lush grass plots lined artistically crafted walking paths, illuminated by electric lights (left) . Bright white building designed in Renaissance style reflected ancient Greek and Roman influences (Figure 7) and possessed strenuous constraints on color, scale and height. The strict application of artistic consistency and simplicity produced a harmonious environment to all attendees. Though the architecture created the appearance of success and stability, the exposition was merely an illusion of prosperity. The clean “White City” had no resemblance to the rough and untamed Trans-Mississippi wilderness that the exposition claimed to be the source of their economic success. The trees and shrubs were transplanted onto the original landscape to create the illusion of mature landscapes and fertile soil. The buildings were inherently temporary – constructed of plaster of Paris and horsehair – since they were only intended to survive the short duration of the 5-month exhibition and then destined for immediate demolition. The purpose of the Omaha World’s Fair was to initiate lasting economic growth following the financial panic, yet the founders had no intention of maintaining the environment or circumstances that would promote further financial prosperity following the exposition’s conclusion.

Omaha did experience some transient financial benefits due to its successful execution of Trans-Mississippi Exposition. The fair attracted over 2.6 million visitors to the city of Omaha over the short five-month duration of the fair. Planners generated a sufficient profit to recoup the expenditure of $2.5 million to put on the Exposition. Nebraska’s government sponsored the Nebraska Exposition for $100,000, and leveraged its local resources to great effect, reaping significant short-term financial gains through its infrastructure and by prominently featuring its agricultural bounty . Visiting delegations, such as Illinois, also poured significant financial investments into the fair. The Illinois delegation regarded the Trans-Mississippi Exposition of paramount importance in its reports to the governor, since the fair would provide a stimulus for Chicagoan industry. Their expenditures were unequivocally reimbursed in returns from the committee and through advertising for Chicagoan business, affluence, and luxuries. All the delegations present at the Omaha Exposition were involved for profit, and Omaha took advantage of its position by exhibiting its hospitality and luxuries. Omaha’s immediate financial success was due to its ability to thoroughly project the inherent potential of Western land and resources throughout all aspects of the exposition.

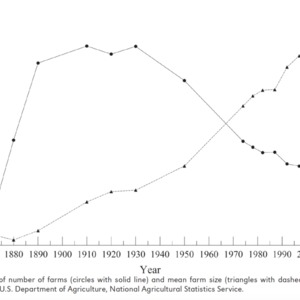

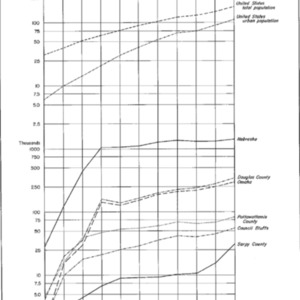

Despite its immediate financial benefits, Omaha did not experience its predicted, long-lasting settlement and success. The number of Nebraskan farms leveled off around 1890, which coincided with the period of agricultural failures in the Panic of 1893 (Figure 8). However, the number of farms did not increase following the Trans-Mississippi Exposition, as the stagnant trend following the recession continued. Population changes followed the same trend: dramatically increasing into the 1890s, stagnating during the decade, but failing to resume its upward climb following the close of the exposition (Figure 9). Though the fair experienced an initial financial boost, its predicted lasting effects were a bust.

A capitalist ethos of commodified nature and endless growth permeated the Omaha World’s Fair. From this perspective, industrious westerners viewed capital as exogenous from nature. Nature was a commodity, and resources were simply reduced to substances to be used by humans. Jason Moore has argued that capitalism promoted this dualistic mindset, which ultimately separated humans from the environment with profound, global consequences. The objective and the execution of the Trans-Mississippi Exposition precisely illustrate this duality. Acquisition of capital was the motivating force for creating the exposition, and the event itself worked to convince other Americans to join the pioneering effort to use the Western resource frontier to create wealth. In a public address, Gurdon Wattles, the President of the Trans-Mississippi Association, explicitly named the goal of the exhibition to be an “advancement of commercial interests of the West, a demonstration of the marvelous resources of the great West.” The fair promoted the improvement of Western territories and in doing so, converted nature to resources to wealth, unclaimed wilderness to Western Civilization. Moore, in The Capitalocene, remarks that “capital… forms independently of the web of life, and intervenes… intruding in, and interrupting, a pre-given ‘traditional balance between humanity and nature.’” Moore states that capitalism depends on the frontier; although the centrality of capitalism is the commodification of everything, it is the frontier that underpins the acquisition of capital. More specifically, the methods to sustainably tame this untouched nature are disparate from the methods that Western settlers used and the age of World’s Fairs glorified.

Although practices that promote profit maximization are logical from capitalist perspectives, they become illogical in ecological contexts. Capitalist production utilizes this separation of humans from nature to view natural resources as disposable commodities, in which the exploitation of these commodities results in profits, yet also often degrades the environment of its source. In ecological matters, this process occurs without feedback or regulation until overproduction or resource depletion occurs, where profitability declines and environmental destruction endures. The cycle of an expedited profit boom and following bust from the Trans-Mississippi exposition illustrates this cycle of exploitation and the resulting ecological impacts.

The Omaha World’s Fair exceeded their goal of financial revitalization in the short duration, and therefore attempted to prolong their success. However, the bust arrived almost immediately following the closing of the fair. Although remnant funds from the exposition were intended for a new exposition, much of the board who had conducted the previous year’s Exposition were unwilling to accept the responsibility of a second Exposition. The novelty of the Trans-Mississippi grounds and image had lost its shine. After the physical fairgrounds structures had outlived their use and profitability, the buildings were hastily destroyed or removed from the North Omaha site. The majority of the demolished material shipped to Chicago by freight cars, but the plaster sculptures and exteriors of buildings were discarded into the emptied lagoon. The exposition physically transformed the North Omaha landscape for the purpose of temporary financial gain, but once the financial payoff began to decline, the fairgrounds were entirely trashed and forgotten with no remnants remaining. The extremely temporary lifespan between construction and demolition, and similarly the exposition’s investment and payoff, portrays the culmination of all societal, economic and environmental perspectives influencing the Trans-Mississippi Exposition.

The inception of the exposition was financially motivated in response to the Financial Panic of 1893 in hopes of accruing wealth. In order to combat the recession, Western inhabitants utilized untouched Western resources as disposable substances for capital gain. The perspective of nature existing independent of humans originated from a capitalist ethos, which justified this exploitation of nature for quick financial gain. Likewise, the construction of the exposition fairgrounds mimicked the exploitation of the environment. The land of North Omaha transformed for the purpose of economic gain, and certainly not in a Lockean sense for its improvement. The buildings were structurally deficient and the landscaping unnatural and artificial. Once profits declined, the city demolished the fairgrounds and erased any actual remnant of the exposition from the Omaha landscape. Today, the only trace of the fair is a small park located on top of the plaster-filled lagoon. Commercial businesses and residential areas now occupy the previous location of the White City. The Trans-Mississippi Exposition strived to instill a lasting economic change, but since it was inherently tied to capitalist economic cycles, the successful boom was followed by the inevitable bust. The technological advances showcased at the fair eventually allowed Western economies to flourish, yet this was in not a direct result of the Exposition’s efforts. Though its legacy is largely forgotten, Omaha eventually evolved into a prosperous metropolis, which satisfied the initial goal of the Trans-Mississippi Exposition.

The 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition exists as a metaphor for the boom-and-bust nature of capitalism in the developing West. All facets of the exposition illustrated these cyclic patterns, ranging from the physical construction and demolition of the exposition buildings to its impact on the local economy. Boom-and-bust financial cycles were fundamental and recurrent phenomena in capitalist economies in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Since the 1970s, environmental historians have critiqued the predominant economic interpretation of these cycles, emphasizing their connections to western expansion. A “capitalist ethos” reframed nature as resource and incentivized the utilization of Western resource frontiers for financial gain. Omaha’s economic success in the 1890s reflected in the exposition’s ability to market the untamed Western land purely as substances ready for new settlers to exploit. This capitalist ethos originated from the idea that humans are separate from nature, a mindset that resonated throughout the exposition, what Jason Moore refers to as Cartesian dualism that prevails in practice. This rejection of ties with the natural environment enabled drastic overexploitation, without consideration for future viability. The Omaha Trans-Mississippi International Exposition represented the cyclic pattern of success and decline caused by many similar dualisms, evidenced in the exposition’s physical construction as well as its fluctuating economic outcomes.

The Omaha 1898 International Exposition pamphlet (Figure 1) was a commemorative item and a contemporary guide for attendees of the 1898 Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition. It was distributed beginning in June during the 1898 festival and provided 32 pages of detailed exhibit coverage. It supplied visitors with necessary information regarding available amenities and transportation around Omaha, a comprehensive exhibit guide, and details about the available diversions, including carnivalesque swordsmen, mazes, and funhouses. The pamphlet first describes the layout of the exposition as a guide for navigation. The exposition grounds consisted of Renaissance-style buildings surrounding a lagoon (Figure 3). Nearly half the pamphlet consisted of photographs of these architectural installations. The classical, palatial aesthetic of the Omaha Exhibition was proudly lauded, illustrating the grandeur of the fair.

The pamphlet enumerates the exhibits housed within each of the state buildings, as well as exhibits documenting substantial achievements. Specific care is taken describing the special exhibits. The government exhibit (Figure 4) displayed exotic artifacts, such as a draft of the Declaration of Independence, and featured military and educational advancements that promoted imperialist sentiments. The Indian Exhibit, when juxtaposed with the exposition’s impressive shows of classical architecture, technology, and material wealth, emphasized the progress of colonialism. Other major exhibits, such as the Agriculture (Figure 5), Electricity, and Machinery buildings, presented the technological advancements and the resources wrought by these newfound processes in order to glorify the technological progress and economic opportunity in the West.

The Exposition celebrated western technology and colonial progress, and their relationship to economic opportunity, though the fair itself was an opportunity for financial gain. Ironically, this fair celebrating western progress originated when the entire nation was recovering from the Financial Panic of 1893. Western states were disproportionately impacted by the panic and therefore especially determined to revitalize their economic prospects. Several macroeconomic problems initiated the beginning of an economic recession; however, the addition of unexpected Western crop failures pushed a common depression into a financial panic. These agricultural shocks were most prevalent in the Western and North Central states, including Nebraska, which caused bank failures that were strongly concentrated in Western states. National and Eastern banks, which were less influenced by the struggling Western agricultural markets, did not experience the same magnitude of the recession following the panic. However, rural banks depended on the success of nearby farms, so local and state banks in the West failed more frequently than in other regions.

The Trans-Mississippi Exposition was a direct response to this economic disaster. Shortly after the recession, Omaha leaders determined that an exposition would successfully communicate the financial potential of the West to the rest of the nation and perhaps resurrect the economic stability in the region. The immense, unprecedented success of Chicago’s Columbian Exposition in 1893 inspired several Western leaders to advocate similar projects in their respective cities. In 1894, Nebraskan delegates invited the Trans-Mississippi Congress, a group of men from Western states who promoted the commercial and material interests of their region, to host the next annual meeting in Omaha. After proposing the idea to the Congress in 1895, local Omaha businessmen successfully committed their city to host an exposition.

The 1898 Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition, also known as the Omaha World’s Fair, was one of forty international expositions that occurred during the “Golden Age of Fairs” from 1880-1910. The purpose of the Omaha World’s Fair was to exemplify the fertility and potential of Western farming and manufacturing as a definite pathway to financial success. The initial settlers already utilized the Western resources by growing crops and raising livestock, but many were still skeptical about adopting the pioneer lifestyle. The number of Nebraskan farms drastically increased from 1870-1890, but then growth and settlement stagnated through the 1890s following the agricultural failures from Panic of 1893. The development of new procedures and technologies provided a stronger promise of success for those moving West. William Jennings Bryan, the spokesman for the Nebraska committee of the Trans-Mississippi Congress, stated, “We believe that an exposition of all the products, industries and civilization of the States west of the Mississippi River, made at some central gateway where the world can behold the wonderful capabilities of these great wealth-producing States, would be of great value, not only to the Trans-Mississippi States, but to all the homeseekers in the world.” The planners hoped the exposition would directly combat the previous notion of the West as having low and unpredictable crop yields observed in the Panic of 1893. By projecting Western industrial and agricultural success to the rest of the nation, Omaha leaders sought to attract settlers to utilize the abundant resources in order to boost the local economy.

The desire to project an image of the West’s success and appeal to potential settlers influenced the construction of the fairgrounds itself, though its execution occurred in a temporary and superficial manner. The goal of the architecture and landscaping was to produce the impression of a prosperous civilization: full of order and stability. A two-thousand foot-long lagoon designed to resemble Venetian canals hosted gondola rides as a whimsical form of transportation throughout the fair (Figure 6) . Stately trees and lush grass plots lined artistically crafted walking paths, illuminated by electric lights (left) . Bright white building designed in Renaissance style reflected ancient Greek and Roman influences (Figure 7) and possessed strenuous constraints on color, scale and height. The strict application of artistic consistency and simplicity produced a harmonious environment to all attendees. Though the architecture created the appearance of success and stability, the exposition was merely an illusion of prosperity. The clean “White City” had no resemblance to the rough and untamed Trans-Mississippi wilderness that the exposition claimed to be the source of their economic success. The trees and shrubs were transplanted onto the original landscape to create the illusion of mature landscapes and fertile soil. The buildings were inherently temporary – constructed of plaster of Paris and horsehair – since they were only intended to survive the short duration of the 5-month exhibition and then destined for immediate demolition. The purpose of the Omaha World’s Fair was to initiate lasting economic growth following the financial panic, yet the founders had no intention of maintaining the environment or circumstances that would promote further financial prosperity following the exposition’s conclusion.

Omaha did experience some transient financial benefits due to its successful execution of Trans-Mississippi Exposition. The fair attracted over 2.6 million visitors to the city of Omaha over the short five-month duration of the fair. Planners generated a sufficient profit to recoup the expenditure of $2.5 million to put on the Exposition. Nebraska’s government sponsored the Nebraska Exposition for $100,000, and leveraged its local resources to great effect, reaping significant short-term financial gains through its infrastructure and by prominently featuring its agricultural bounty . Visiting delegations, such as Illinois, also poured significant financial investments into the fair. The Illinois delegation regarded the Trans-Mississippi Exposition of paramount importance in its reports to the governor, since the fair would provide a stimulus for Chicagoan industry. Their expenditures were unequivocally reimbursed in returns from the committee and through advertising for Chicagoan business, affluence, and luxuries. All the delegations present at the Omaha Exposition were involved for profit, and Omaha took advantage of its position by exhibiting its hospitality and luxuries. Omaha’s immediate financial success was due to its ability to thoroughly project the inherent potential of Western land and resources throughout all aspects of the exposition.

Despite its immediate financial benefits, Omaha did not experience its predicted, long-lasting settlement and success. The number of Nebraskan farms leveled off around 1890, which coincided with the period of agricultural failures in the Panic of 1893 (Figure 8). However, the number of farms did not increase following the Trans-Mississippi Exposition, as the stagnant trend following the recession continued. Population changes followed the same trend: dramatically increasing into the 1890s, stagnating during the decade, but failing to resume its upward climb following the close of the exposition (Figure 9). Though the fair experienced an initial financial boost, its predicted lasting effects were a bust.

A capitalist ethos of commodified nature and endless growth permeated the Omaha World’s Fair. From this perspective, industrious westerners viewed capital as exogenous from nature. Nature was a commodity, and resources were simply reduced to substances to be used by humans. Jason Moore has argued that capitalism promoted this dualistic mindset, which ultimately separated humans from the environment with profound, global consequences. The objective and the execution of the Trans-Mississippi Exposition precisely illustrate this duality. Acquisition of capital was the motivating force for creating the exposition, and the event itself worked to convince other Americans to join the pioneering effort to use the Western resource frontier to create wealth. In a public address, Gurdon Wattles, the President of the Trans-Mississippi Association, explicitly named the goal of the exhibition to be an “advancement of commercial interests of the West, a demonstration of the marvelous resources of the great West.” The fair promoted the improvement of Western territories and in doing so, converted nature to resources to wealth, unclaimed wilderness to Western Civilization. Moore, in The Capitalocene, remarks that “capital… forms independently of the web of life, and intervenes… intruding in, and interrupting, a pre-given ‘traditional balance between humanity and nature.’” Moore states that capitalism depends on the frontier; although the centrality of capitalism is the commodification of everything, it is the frontier that underpins the acquisition of capital. More specifically, the methods to sustainably tame this untouched nature are disparate from the methods that Western settlers used and the age of World’s Fairs glorified.

Although practices that promote profit maximization are logical from capitalist perspectives, they become illogical in ecological contexts. Capitalist production utilizes this separation of humans from nature to view natural resources as disposable commodities, in which the exploitation of these commodities results in profits, yet also often degrades the environment of its source. In ecological matters, this process occurs without feedback or regulation until overproduction or resource depletion occurs, where profitability declines and environmental destruction endures. The cycle of an expedited profit boom and following bust from the Trans-Mississippi exposition illustrates this cycle of exploitation and the resulting ecological impacts.

The Omaha World’s Fair exceeded their goal of financial revitalization in the short duration, and therefore attempted to prolong their success. However, the bust arrived almost immediately following the closing of the fair. Although remnant funds from the exposition were intended for a new exposition, much of the board who had conducted the previous year’s Exposition were unwilling to accept the responsibility of a second Exposition. The novelty of the Trans-Mississippi grounds and image had lost its shine. After the physical fairgrounds structures had outlived their use and profitability, the buildings were hastily destroyed or removed from the North Omaha site. The majority of the demolished material shipped to Chicago by freight cars, but the plaster sculptures and exteriors of buildings were discarded into the emptied lagoon. The exposition physically transformed the North Omaha landscape for the purpose of temporary financial gain, but once the financial payoff began to decline, the fairgrounds were entirely trashed and forgotten with no remnants remaining. The extremely temporary lifespan between construction and demolition, and similarly the exposition’s investment and payoff, portrays the culmination of all societal, economic and environmental perspectives influencing the Trans-Mississippi Exposition.

The inception of the exposition was financially motivated in response to the Financial Panic of 1893 in hopes of accruing wealth. In order to combat the recession, Western inhabitants utilized untouched Western resources as disposable substances for capital gain. The perspective of nature existing independent of humans originated from a capitalist ethos, which justified this exploitation of nature for quick financial gain. Likewise, the construction of the exposition fairgrounds mimicked the exploitation of the environment. The land of North Omaha transformed for the purpose of economic gain, and certainly not in a Lockean sense for its improvement. The buildings were structurally deficient and the landscaping unnatural and artificial. Once profits declined, the city demolished the fairgrounds and erased any actual remnant of the exposition from the Omaha landscape. Today, the only trace of the fair is a small park located on top of the plaster-filled lagoon. Commercial businesses and residential areas now occupy the previous location of the White City. The Trans-Mississippi Exposition strived to instill a lasting economic change, but since it was inherently tied to capitalist economic cycles, the successful boom was followed by the inevitable bust. The technological advances showcased at the fair eventually allowed Western economies to flourish, yet this was in not a direct result of the Exposition’s efforts. Though its legacy is largely forgotten, Omaha eventually evolved into a prosperous metropolis, which satisfied the initial goal of the Trans-Mississippi Exposition.

Creator

Maddie Fung

Matthew Mordeson

Matthew Mordeson

Source

Altvater, Elmar. "Ecological and Economic Modalities of Time and Space." Capitalism Nature Socialism 1, no. 3 (1898): 59-70.

Bostwick, Louis, and Homer Frohardt. Shot of Government Building. Digital image. Durham Museum Photo Archive.

Bostwick, Louis, and Homer Frohardt. View of the Agriculture Building. Digital image. Durham Museum Photo Archive.

Dupont, Brandon R. "Panic in the Plains: Agricultural Markets and the Panic of 1893." Cliometrica 3, no. 1 (January 03, 2008): 27-54.

Findling, John. "World's Fair." Encyclopaedia Britannica. September 15, 2017.

Haynes, James B. History of the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition. (Omaha, NE: Committee on History, 1910), 14.

Hiller, Tim L., Larkin A. Powell, Tim D. McCoy, and Jeffrey J. Lusk. "Long-Term Agricultural Land-Use Trends in Nebraska, 1866-2007." Great Plains Research 19 (2009): 225-237.

Kelly, Michael. "Find in Trench Dusts Off Exposition Quests." Omaha World-Herald, June 11, 1980.

Landmarks Heritage Preservation Commission. Patterns on the Landscape: Heritage Conservation in North Omaha. (Omaha, NE: The Commission, 1984), 25.

Maloney, Kathy Jean. World's Fair Gardens: Shaping American Landscapes. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2012.

Moore, Jason W. "The Capitalocene Part I: On the Nature and Origins of Our Ecological Crisis." The Journal of Peasant Studies 44, no. 3 (March 17, 2017): 594-630.

Nebraska State Commission. Report of the Nebraska State Commission for the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition. Omaha, NE: Omaha Printing Company, 1898.

Omaha Daily Bee (Omaha, NE) “Greater America Exposition at Omaha, July 1 to Nov.1, 1899.” June 25, 1899.

Omaha Daily Bee (Omaha, NE) “Only Small Crowd Appears.” July 6, 1899.

Rinehart, F.A. Bird's-eye View Grand Court (Night). 1898. Durham Museum Photo Archive.

Rinehart, F.A. Fine Arts Building. 1898. Durham Museum Photo Archive

Rinehart, F. A. "Grand Court Looking E. (1)" Digital image. Trans- Mississippi & International Exposition. April 5, 1996.;

Rinehart, F. A. "Grand Court Looking E. (2)" Digital image. Trans-Mississippi & International Exposition. April 5, 1996.

Spencer, Jeffrey. East End of Lagoon. 1898. Durham Museum Photo Archive.

"The Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition at Omaha." Scientific American 78, no. 22 (May 28, 1898): 346-47.

Wishart, Ryan. "Coal River's Last Mountain." Organization and Environment 25, no. 4 (November 27, 2012): 470-485.

Worster, Donald. Dust Bowl: The Southern Plains in the 1930s. New York: Oxford University Press, 1979. 6.

Zipay, John P., "The Changing Population of the Omaha SMSA 1860-1967 With Estimates for 1970" (1967). Publications Archives, 1963-2000.

Bostwick, Louis, and Homer Frohardt. Shot of Government Building. Digital image. Durham Museum Photo Archive.

Bostwick, Louis, and Homer Frohardt. View of the Agriculture Building. Digital image. Durham Museum Photo Archive.

Dupont, Brandon R. "Panic in the Plains: Agricultural Markets and the Panic of 1893." Cliometrica 3, no. 1 (January 03, 2008): 27-54.

Findling, John. "World's Fair." Encyclopaedia Britannica. September 15, 2017.

Haynes, James B. History of the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition. (Omaha, NE: Committee on History, 1910), 14.

Hiller, Tim L., Larkin A. Powell, Tim D. McCoy, and Jeffrey J. Lusk. "Long-Term Agricultural Land-Use Trends in Nebraska, 1866-2007." Great Plains Research 19 (2009): 225-237.

Kelly, Michael. "Find in Trench Dusts Off Exposition Quests." Omaha World-Herald, June 11, 1980.

Landmarks Heritage Preservation Commission. Patterns on the Landscape: Heritage Conservation in North Omaha. (Omaha, NE: The Commission, 1984), 25.

Maloney, Kathy Jean. World's Fair Gardens: Shaping American Landscapes. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2012.

Moore, Jason W. "The Capitalocene Part I: On the Nature and Origins of Our Ecological Crisis." The Journal of Peasant Studies 44, no. 3 (March 17, 2017): 594-630.

Nebraska State Commission. Report of the Nebraska State Commission for the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition. Omaha, NE: Omaha Printing Company, 1898.

Omaha Daily Bee (Omaha, NE) “Greater America Exposition at Omaha, July 1 to Nov.1, 1899.” June 25, 1899.

Omaha Daily Bee (Omaha, NE) “Only Small Crowd Appears.” July 6, 1899.

Rinehart, F.A. Bird's-eye View Grand Court (Night). 1898. Durham Museum Photo Archive.

Rinehart, F.A. Fine Arts Building. 1898. Durham Museum Photo Archive

Rinehart, F. A. "Grand Court Looking E. (1)" Digital image. Trans- Mississippi & International Exposition. April 5, 1996.;

Rinehart, F. A. "Grand Court Looking E. (2)" Digital image. Trans-Mississippi & International Exposition. April 5, 1996.

Spencer, Jeffrey. East End of Lagoon. 1898. Durham Museum Photo Archive.

"The Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition at Omaha." Scientific American 78, no. 22 (May 28, 1898): 346-47.

Wishart, Ryan. "Coal River's Last Mountain." Organization and Environment 25, no. 4 (November 27, 2012): 470-485.

Worster, Donald. Dust Bowl: The Southern Plains in the 1930s. New York: Oxford University Press, 1979. 6.

Zipay, John P., "The Changing Population of the Omaha SMSA 1860-1967 With Estimates for 1970" (1967). Publications Archives, 1963-2000.

Collection

Citation

Maddie Fung

Matthew Mordeson, “Trans-Mississippi Exposition,” Omaha in the Anthropocene, accessed April 26, 2024, https://steppingintothemap.com/anthropocene/items/show/26.

Embed

Copy the code below into your web page