Husker Football

Title

Subject

Description

Sport fandom is a universal language that unite communities, evoking passionate response among its participants. In Nebraska, college football is king. On game day, upwards of 90,000 people attend home games. It is not unfair to imagine that most fans pay little attention to the environmental impacts of their sport. Historians have studied the impacts of sports and its importance to different cultures. The sports fandom culture it creates has a major impact on the Anthropocene. Global sport fandom has become a phenomenon, and its expansion since the mid-1900s has had profound environmental effects. The sport of football has a significant environmental impact in the anthropocene through the waste it creates, the ecosystems it alters, and its overall carbon footprint it generates. The significance of sports fandom as a global cultural phenomenon is only matched by its environmental significance in the Anthropocene.

This Nebraska Huskers commemorative football, housed in the Durham Museum lists the career awards and achievements of Eric Crouch. (Figure I and II) Eric Crouch is not only relevant in terms of his importance in the history of Husker football, but he is relevant in the history of the city of Omaha, as this is his hometown. Crouch grew up as the son of a single mother who was a medical technician by day and a waitress by night in Omaha (Lapointe, 2001). One of his biggest mentors was a Creighton faculty member, Dr. Jim Brown, who was a radiologist (Lapointe, 2001). Crouch went on to become a very well-known and successful Husker football player, known by Husker fans for two major scoring plays in his Junior season. One being a 95-yard touchdown scramble, the other being a trick play against Oklahoma to seal what was a close game (Lapointe, 2001). Being from Omaha, Crouch was a fan favorite and ties Omaha into Husker football history.

College football fandom feeds from and builds upon cultural and social norms that support a team. (Satterfield and Godfrey 2011). Like many sports cultures around the world, football culture operates through a set of rules. Rules such as showing loyalty on game days by wearing school colors and team jerseys (Satterfield and Godfrey 2011). A community develops that defines itself by the wins and losses of its team. The success of the team’s performance affects the behavior of the community. A successful team is more likely to draw in more supporters and increase their fanbase. The connection between the team and the community is especially strong in a small college town (Satterfield and Godfrey 2011). The importance of college football to Nebraskans is amplified by the absence of professional sports teams in the state. The lack of competition among other sports and a large student population results in attendances regularly over 90,000 for Nebraska home games (Satterfield and Godfrey 2011).

Nebraska football fandom in particular has been found to not be primarily rooted in the team’s success, or its geographic location, or even a fan’s association with the university. Rather, their fandom and attachment to the Husker football team is due to what it stands for. The team stands for the state of Nebraska and what Husker fans believe to be their way of life or set principles that represent the state’s dominant agrarian culture. As a result, Husker fans tend to equate their fandom of the football team to being part of what it means to be a Nebraskan (Earnheardt et al, 2013).

The historic growth of Nebraska football fandom is most clearly expressed in the construction and expansion of Memorial Stadium. Figure III shows the initial construction of the Memorial Stadium in Lincoln, Nebraska in 1923. The stadium was built to replace Nebraska Field which previously hosted all Husker home games. The construction of buildings by Nebraska Field reduced its seating capacity. As Nebraska’s fan base grew in popularity, a new stadium with more seating arrangements were required (“Memorial Stadium” 2005). (Figure IV) The use of a horse drawn plow alters the soil and the cutting down of trees to clear the area for construction also changes the landscape and the ecosystem. The altering of the ecosystem can result in loss of many habitats for the local fauna. The construction of the stadium also contributes to urbanization and the subsequent loss of farmland.

College football had its roots in America in the late 18th century. Schools in the Northeast each had a different version of football (PFRA). The first official college football game wasn’t until 1869 between Princeton and Rutgers. This game attracted about a hundred supporters cheering on their team despite the cold, windy conditions (PFRA). The game soon spread to other ivy league schools such as Harvard, Yale, and Columbia. The popularity of the game was noticed by colleges around the nation and many other schools began to start programs dedicated to football (PFRA). College football has managed to retain its passionate fanbase that initially made it popular. A survey from September 2, 2007 indicates that college football is the third most popular sport after professional football and baseball with thirteen percent of the sample (PR Newswire 2007). This indicates that even after the introduction of new sports such as basketball and soccer, college football has managed to retain its popularity among the public.

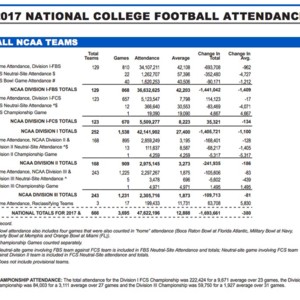

By the 2000s, college football transformed into a big business. Football games around the nation recorded an attendance of 36 million over the course of 129 games in the NCAA Division I-FBS subdivision with an average of 42,000 spectators for each game (NCAA 2017). (Figure V) NCAA Division I football also recorded a median revenue of $63 million in 2015 (NCAA 2016). These figures are also expected to increase every year. The increasing demand led to many stadiums expanding their capacity. For example, Texas A&M spent an incredible $485 million to expand their stadium (Patterson 2018). The expansion projects are designed to increase seating capacity and provide more facilities for the fans. The new stadium also provides increased facilities to players and in hopes of attracting new recruits. Many colleges rely on their football programs as their main source of revenue (Patterson 2018).

Football, ranging from high school to the professional level, has become a billion-dollar industry (Massengil 2016). This industry provides entertainment and jobs for thousands of people across the nation. Historian Taylor Rhodes argues that college sports are especially significant in geographically isolated cities like Lincoln, Nebraska. These cities experience a significant increase in employment and tax revenues from hosting college football games (Rhodes 2013). Major sporting events such as the NFL Super Bowl, the Olympics, and the FIFA World Cup promise fame and fortune to host cities (Warren 2017). This large economic benefit results in the negative environmental impacts being overlooked (Massengil 2016).

One negative impact is air pollution. Environmental scientist Tanushree Dutta and colleagues explain that large scale assemblies of people gathering in confined spaces can have significant impacts on the local air chemistry due to human emissions of volatile organics (Dutta et al, 2016). These variations in air quality in such a small scale can be studied by quantifying fingerprint volatile organic compounds such as acetone, toluene, and isoprene. All of these can be found in large scale assemblies of people such as concerts, movie screenings, and of course sporting events such as the Olympic or the FIFA World Cup (Dutta et al, 2016). During the 2014 FIFA World Cup in Brazil, average attendance of over 50,000 fans per game totaled more than 3.4 million people during the whole event (Dutta et al, 2016). Large scale attendance numbers aren’t just restricted to events such as the Olympics and the World Cup but can also be seen on local scales as well. Nebraska Cornhusker football games are just one of many examples of this local scale gatherings in the United States. Roughly 90,000 people attended Husker football games on game days in Lincoln, NE in 2016 (KETV, 2016). Overall, 631,000 fans total attended home games that season, and over 1 million fans total attended home and away games (KETV, 2016). The sheer number of fans that attend these sports teams makes sense as to why teams nationally and globally would expand and further construct their stadiums to meet these capacities. This expansion of stadiums can relate back to the environmental impacts of gameday.

Stadiums produce significant waste during game days. (Figure VI) In addition to the waste generated, stadiums also use up a great amount of energy. For example, the 2012 Super Bowl in Indianapolis was estimated to have consumed 15,000 megawatt hours of electricity (Massengil 2016). This is enough electricity to power 1,400 homes across the nation for an entire year. In addition to the energy consumption by the stadium itself, 111.3 million viewers consumed more electricity to watch the game (Massengil 2016). The carbon emissions that result from game day are also a significant concern. Carbon emissions are a major proponent of climate change. A study conducted by researchers at Cardiff University in the U.K. in 2007 examined the ecological footprint of an FA Cup Final, the premier event of English domestic soccer. The footprint included traveling energy consumption, food and drinks consumed at the end, and the stadium infrastructure. The results showed that the estimated event footprint was about 3000 global hectares with more than half comprising of travel energy consumption (Collins et al, 2009).

The footprint estimate would be similar to a major football bowl game in the United States. Construction projects, which include sports stadiums, consume 60 % of the nation’s raw materials annually (Grant, 2014). The construction projects failed to use local or recycled product that could reduce their environmental impact addresses Thomas Grant Jr. (Gant, 2014). The construction and personal vehicle of stadiums contribute to air pollution and carbon dioxide emissions. This was evident after the construction of the new Yankee stadium which significantly increased air pollution in an already congested part of New York City (Porteshawyer 2009).

Fandom is also expressed in travel. In the post-realignment era in Division I sports, teams of all sports (not just football) have had to travel larger distances due to a growing geographical footprint of these conferences. One way that college football in the United States has had an effect on the environment in terms of energy used on game days can be seen when the NCAA Division I athletic conferences underwent conference realignments. Conferences such as the Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC), the Big Ten Conference (B1G), the Big 12 Conference, the Pac-12 Conference (Pac-12), and the Southeastern Conference (SEC) make up what is known as the Power 5 Conferences in division I college football (Farley et al, 2017). What Farley and his colleagues found during their study was that sports do, in fact, have a major impact on the environment. In almost every case in their study, the expansion of the Power 5 Conferences caused average emissions to rise. The only conference that did not rise in emissions was the one that already had the largest average emissions per game and highest total emissions, the Pac-12 Conference (Farley et al, 2017). While colleges have focused more attention on the sustainability of their campuses and at stadiums, travel-related environmental impacts have risen (Farley et al, 2017). This problem of transportation related emissions on game days can also be seen in Husker football, as many fans travel from Omaha to Lincoln and back in their cars to attend these home games. For their first home game in 2018, stadium officials expected a turnout of 100,000 with thousands driving from Omaha to attend the game (Patterson 2018). The large number of commuters impacts the transportation related emissions.

The impact of sport fandom occurs globally and is not just restricted to America. The Olympics is an event that unites sports fans worldwide. It can also lead to environmental problems for the host country. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil hosted the summer Olympics in 2016. This was an exciting venture for the city, but it also led to many environmental concerns. This included the 3.6 million tons of carbon dioxide emitted during the duration of the event (Frontier 2016). In addition to this, there was an estimated 17,000 tons of waste produced, 23,500 liters of fuel consumed, along with almost 30,000 gigawatts of electricity used throughout the Olympics (Frontier 2016). The environmental impacts of global sport fandom such as carbon dioxide emissions and waste produced have lasting impacts on the anthropocene.

To avoid such traffic congestion, there was once even an attempted ban of a football stadium in New York City in 2004. Groups such as the Straphangers Campaign and the Tri-State Transportation Campaign were arguing that the city’s environmental review underestimated the number of fans that would travel to the stadium on the West side of New York on game days via cars or taxis. The groups argued that this would result in traffic congestion and pollution in a neighborhood that already had problems in both of those areas (Bagli, 2004). The review estimated that anywhere between 68 and 75 percent of the fans would travel to games by foot, but they were mistaken. The actual percentage of fans that travel on foot ranges from 52 percent at Pacific Bell Stadium in San Francisco, to 17 percent at Shea Stadium in Queens (Bagli, 2004). A reason for choosing car travel over other methods was explained by Robert Paaswell, director of the University Transportation Research Center at City College. He said that going to a football game is considered, “leisure travel, not business travel, so people don't have to travel by transit. They go with friends, go out for lunch or for beers afterward. You want to get there early, and you don't want to deal with a fixed schedule. A car is the most attractive way to go” (Bagli, 2004). This incident is yet another example of the concerns of traffic congestion and air pollution that can be seen on football game days.

Despite all of the negative impacts that can be seen from football game days, or mass sporting events in general, there is still some positive things students and fans can do to try and make these events greener. According to Kristen Domonell, successful efforts at campuses across the country include: solar arrays at 10 sporting facilities at Arizona State University, wind turbines that supply 30% of the power to North Texas University’s football stadium and nearby buildings, and the switch to all compostable or recyclable concession packaging at the University of Washington’s Husky Stadium (Domonell, 2013). If more universities, including the University of Nebraska at Lincoln Cornhuskers, would be able to implement efforts such as these, then it would help cut down the environmental effects that are seen on game days.

The sport of football brings joy to millions of people across the nation. While we are celebrating a victory or enjoying the unity of supporting a team, we must remember the environmental effects caused by football and other major sports and work to address them.

Creator

Brody Methven

Source

Collins, Andrea, Calvin Jones, and Max Munday. "Assessing the Environmental Impacts of Mega Sporting Events: Two Options?" Tourism Management 30, no. 6 (2009): 828-37. Accessed November 7, 2018.

KETV. "Nebraska Football Team Ranks in Top 10 in Average Attendance in 2016."

Lapointe, Joe. 2001. “FOOTBALL; Crouch Has Matured Beyond His 23 Years”. New York Times, December 28

Memorial Stadium Construction June 30 2006. In Huskers.com. Accessed October 9, http://www.huskers.com/PhotoAlbum.dbml?DB_OEM_ID=100&PALBID=105.

Memorial Stadium Picture after a Nebraska Touchdown. In Huskers.com. Accessed October 9, 2018. http://www.huskers.com/PhotoAlbum.dbml?DB_OEM_ID=100&PALBID=105.

"2017 Football Attendance." NCAA. 2017. Accessed December 13, 2018. http://fs.ncaa.org/Docs/stats/football_records/Attendance/2017.pdf.

"Revenues and Expenses." NCAA. 2016. Accessed December 13, 2018. http://www.ncaapublications.com/productdownloads/D1REVEXP2015.pdf

Construction on Memorial Stadium took place during the summer of 1923. In Huskers.com. Accessed October 9, 2018.http://www.huskers.com/PhotoAlbum.dbml?DB_OEM_ID=100&PALBID=105

Patterson, Thom. "Eye-popping College Football Stadium Pricetags." CNN. September 28, 2018. Accessed December 14, 2018.

"While Still the Nation's Favorite Sport, Professional Football Drops in Popularity." Razor Tie Artery Foundation Announce New Joint Venture Recordings | Razor & Tie. Accessed December 13, 2018. https://web.archive.org/web/20070902220050/http://sev.prnewswire.com:80/sports/20070109/NYTU17309012007-1.html.

Bagli, Charles V. 2004. “Environmental Review Stirs Doubt About Stadium Plan.” New York Times, December 22.

Collins, Andrea, Andrew Flynn, Max Munday, and Annette Roberts. 2007. “Assessing the Environmental Consequences of Major Sporting Events: The 2003/04 FA Cup Final.” Urban Studies (Routledge) 44 (3): 457–76.

Dutta, Tanushree, Ki-Hyun Kim, Minori Uchimiya, Pawan Kumar, Subhasish Das, Satya Sundar Bhattacharya, and Jan Szulejko. 2016. “The Micro-Environmental Impact of Volatile Organic Compound Emissions from Large-Scale Assemblies of People in a Confined Space.” Environmental Research 151 (November): 304–12.

Domonell, Kristen. 2013. “Sustainable Game Days.” University Business 16 (10): 16.

Earnheardt, A. C., Haridakis, P. M., & Hugenberg, B. S. (2013). Sports fans, identity, and socialization exploring the fandemonium. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Farley, Bradley, Lisa M. DeChano-Cook, and Lucius F. Hallett IV. 2017. “Environmental Impact of Power Five Conference Realignment.” Geographical Bulletin 58 (2): 93–106.

Frontier. "The Environmental Impact Of The Olympics." HuffPost UK. August 19, 2017. Accessed December 14, 2018.

Grant, Thomas, Jr. "Chapter 2. Impact Studies and Other Quantitative Analyses: Inconclusive Conclusions." The Sports Franchise Game 25, no. 1 (January 1, 2014). Accessed October 9, 2018. doi:10.9783/9780812209150.13.

Massengill, Mitchell. "Tackling Football's Environmental Impact." Energy and Environmental Policy 2016. November 28, 2016. Accessed October 10, 2018.

"Memorial Stadium." UNL Historic Buildings - Burnett Hall. Accessed December 13, 2018. http://historicbuildings.unl.edu/building.php?b=38.

Patterson, Thom. "Eye-popping College Football Stadium Pricetags." CNN. September 28, 2018. Accessed December 14, 2018.

Porteshawver, Alex. "Green Sports Facilities: Why Adopting New Green-Building Policies Will Improve the Environment and the Community." Marquette Sports Law Review20, no. 1 (2009).

PFRA Research. "No Christian End! The Beginnings of Football in America." Professional Football Researchers Association. Accessed December 13, 2018. http://www.profootballresearchers.com/articles/No_Christian_End.pdf.

Rhodes, M. Taylor, 2013. "Pigskin, Tailgating and Pollution: Estimating the Environmental Impacts of Sporting Events," UNCG Economics Working Papers 13-19, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Department of Economics.

Satterfield, J., & Godfrey, M. (2010). The University of Nebraska-Lincoln Football: A Metaphorical,Symbolic and Ritualistic Community Event. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 12(1).

Rhodes, Taylor. "Pigskin, Tailgating and Pollution: Estimating the Environmental Impacts of Sporting Events." October 21, 2013. Accessed November 7, 2018. http://faculty.lawrence.edu/rhodesm/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2013/10/draft_v48_environ_jmp_10_2013.pdf.

Warren, Gina. "Big Sports Events Have Big Environmental Footprints. Could Social Licenses To Operate Help?" Forbes. December 11, 2017.

Collection

Citation

Embed

Copy the code below into your web page