Coffee Cans

Title

Coffee Cans

Subject

Omaha businessmen William Paxton and Benjamin Gallagher started gas-roasting coffee in 1887. Their factory stood across the street from the current location of The Durham Museum on 10th and Jones. The pair launched Butter-Nut Coffee in 1916 and employed hundreds of Omahans.

Although a local hit for decades, the coffee beans used by the “Butter-Nut” brand were anything but local. The coffee beans grew thousands of miles away. Butter-Nut farmed their beans on plantations in 18 different tropical countries. These plantations used either sun or shade-grown coffee. Sun-grown coffee is grown in the sun, whereas shade grown coffee grows under the canopy of trees. Large businesses, like Butter-Nut, preferred sun-grown coffee, which requires massive deforestation. This led to habitat loss, sometimes putting species at risk for extinction. Declines in tropical ecosystems and species diversity are part of the Anthropocene. Not only does coffee start our day, it changes the places where it is grown.

Although a local hit for decades, the coffee beans used by the “Butter-Nut” brand were anything but local. The coffee beans grew thousands of miles away. Butter-Nut farmed their beans on plantations in 18 different tropical countries. These plantations used either sun or shade-grown coffee. Sun-grown coffee is grown in the sun, whereas shade grown coffee grows under the canopy of trees. Large businesses, like Butter-Nut, preferred sun-grown coffee, which requires massive deforestation. This led to habitat loss, sometimes putting species at risk for extinction. Declines in tropical ecosystems and species diversity are part of the Anthropocene. Not only does coffee start our day, it changes the places where it is grown.

Description

Thomas Jefferson called it “the drink of the civilized world,” it has been cultivated since the fifteenth century, and there is a very good chance you started your day with it. It is consumed recreationally, to promote wakefulness and productivity, and often just for the taste. Today, coffee is the most popular beverage in the world, with 400 billion cups consumed annually. (Morris, 2013)

Grown in the “Bean Belt-” the area between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn - and shipped globally, coffee can be found in our stores, our homes, and in the factories that process beans. It is no surprise why coffee is popular. It’s flavors... the cultural significance… its mild addictiveness… but how it achieved such prominence is a fascinating story that connects the rise of cities with different environments. It is a tale of the Anthropocene. We are surrounded by evidence of that story, whether in the form of coffee cans on our shelves or the immense fields of coffee beans in distant countries. You drink that story with every sip of coffee. The Butter-Nut Coffee can represents Omaha’s place in that story. The commodity chain developed over the last 150 years to bring coffee into our homes and businesses speaks to dramatic changes the coffee industry has had on the global environment.

Coffee traveled long and far to end up in the roasters that supplied Butter-Nut Coffee. The bean was first described in writing to be a beneficial crop as early as 1000 CE by Avicenna of Bukhara (in modern-day Uzbekistan), and scholars have found evidence of widespread coffee drinking during the mid-15th century after it found its way to Mecca. From there, coffee traveled along trade routes and became an instant hit wherever it was available. Cafes became popular places to meet in 17th century Europe, and the beans were already being exported to America by 1668. (Luttinger and Dicum, 2006) A crop with such a global popularity does not enter our lives unnoticed. “Only a handful of consumer goods have fueled the passions of the public as much as coffee. [It] has inspired battlefields of economics, human rights, politics, and religion” while becoming a part of our everyday lives thanks to the chemical composition responsible for its habit-forming properties and enjoyable taste. (Luttinger and Dicum, 2006)

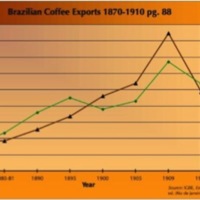

By the early 18th century, obsession with coffee expanded to the US. Coffee consumption was on par with tea domestically until the 1880s, when an influx of immigrants hoping to have the economic ability to purchase coffee began to settle in the US. (Morris, 2013) It was not a specific taste for coffee that the immigrants sought, but rather, they yearned for the financial agency to obtain coffee - something that could be done in America, as argued by coffee historian Jonathan Morris, PhD. Around this time, various manufacturers of coffee began to notice an uptick in demand of an already popular product and acted accordingly, importing increasing amounts of beans from source countries like Brazil. (Figure 1) Speaking on the early dramatic rise of coffee consumption in America, notable coffee historian Steven Topik describes how “consumption ballooned from under one pound [per capita] at independence to nine pounds in 1882,” leading to the US consuming one-fifth of the world’s coffee at this time. (Topik, 2013) Paxton & Gallagher as suppliers would ultimately create a coffee powerhouse in the Midwest during this popularity surge - and would be the first producer to sell coffee in tin cans, as opposed to loose beans, in the state of Nebraska. (Landale, 1945)

The story of coffee in Omaha began long after it was found that coffee beans could be stewed into an energizing elixir. Omaha businessmen William Paxton and Benjamin Gallagher enjoyed success across several industries and rose to prominence in the late nineteenth century thanks to their investments and ties to other prominent capitalist families like the Creightons. (NSHS, 2010) In 1879, the pair established a trading post that enjoyed success along the rail lines they helped to build, and by 1887 they were roasting beans for distribution on 10th and Jones streets in Omaha. (OWH. 1994)(Figure 2) The unique process used gas instead of coal to roast the imported green coffee faster, reducing the detrimental effects of prolonged heat exposure while still achieving the desired characteristics in an effort to preserve the freshness and flavor of the coffee. (OWH, 1915)

Paxton & Gallagher used their method as a unique selling point, bragging to audiences about how they spare no expense to produce the best product. “Gas roasting means something,” says an ad in an April 1915 printing of the Omaha-World Herald. “The Omaha Gas Company will tell you that we are the biggest gas consumers in the city. You can use your own judgment, for we certainly would not pay them over $500.00 a month for gas to roast our coffee if we could do it by using coal for $50.00 a month.” (OWH, 1915) This advertisement reveals to us the efforts that Paxton and Gallagher made in creating their product, while also showcasing their immense gas consumption. This braggadocio with respect to energy consumption is a trait of the Anthropocene, as it demonstrates the ideal of producing as much product as possible with little thought to possible impacts. Beans first arrived via railroads and were stored onsite. (OCCJ, 1936) After being fed through pneumatic tubes in 120 pound increments, the beans were dumped into one of several sixty-foot-long roasters. (The Spice Mill, 1911) After twenty minutes of roasting, the roasted and ground blend of coffee was then packaged in two pound red coffee cans vacuum-packed to preserve taste - a new development for coffee in the early 20th century that gave Paxton & Gallagher a marketable advantage. (The Spice Mill, 1911) These cans were emblazoned with “PAXTON GAS ROASTED COFFEE,” much like the first coffee can artifact from The Durham Museum, which can lead one to reasonably conclude that this can was created around 1915. (Figure 3)

This can lands a spot in The Durham thanks to the large role that Paxton & Gallagher had in shaping the Omaha economy through their roastery, among other ventures. Their coffee brand would only grow for most of the 20th century. Shortly after the production of this can, Paxton & Gallagher launched the Butter-Nut line of foods, which included coffee. Named after a tree nut, this rebranding was an attempt to describe their sweet-smelling product and launch a successful effort that would increase its reach to other states. The number of employees at the roastery on 10th street grew with increased demand, doubling in size to 150 between 1939 and 1942. (Landale, 1945) Butter-Nut directly impacted the economic scene in Omaha by employing a steady, local workforce.

As demand for coffee increased and Butter-Nut’s sales grew, competitors began eyeing the corporation. In 1958 the coffee line was bought by Clark and Gilbert Swanson, and was then acquired by Coca-Cola in 1964 thanks to a stock transition worth $30 million. (Coca-Cola, 1969) It is during this time under Coke that the second coffee can was produced - likely in the late 1960s.(Figure 4) Its design changes reflect ideals of modernization that were driven by the commercial consolidations that produced the can. With company structures changing through acquisitions and time, the can designs were periodically updated to appeal to consumers. In 1989, Butter-Nut was sold to an investor working for Maryland Club Foods, and later that year was finally sold to Procter & Gamble, where a Butter-Nut variant of Folger’s was produced. (United Press International, 1989) The flavor was discontinued and Folger’s was sold to Smucker’s, which accounts for 69% of today’s coffee sales along with the remaining “Big Five” coffee producers. (Morris, 2013) Butter-Nut Coffee distinguished itself from the competing brands of its time through its unique taste and aroma.

As its popularity grew exponentially, the Butter-Nut Coffee swiftly established itself as a common household brand and found its way into millions of homes across the Midwest. Butter-Nut faced two primary obstacles that blocked the growing company’s path in maximizing their profit margins, both of which were derived from the biological nature of the coffee bean itself. One limitation is the fact that coffee beans will only grow in tropical climates that exist in certain geographical locations. The collective growing sites of coffee around the world is known as the coffee belt which, “spans the globe along the equator, with cultivation in Central and South America; the Caribbean; Africa; the Middle East; and Asia. Brazil is now the world’s largest coffee-producing country.” (Scott, 2015) (Figure 5) While Butter-Nut could process and distribute its product in North America, they had to import the coffee beans, “from the 18 producing countries in Central America, South America, and Africa.” (OWH, 1959)

The second obstacle the company encountered was the unpredictable events affecting coffee yields from Butter-Nut’s eighteen producing countries. The motivation to overcome this challenge is due to the rising demand and the consumer’s expectation of the product’s quality which both had to be met in order to maintain the company’s gain in capital. This is evident in the Seventy Fifth Anniversary Cook Book, produced by the Paxton and Gallagher company in 1939. (Figure 6) When describing the origin of their coffee they state that maintaining adequate amounts of their product, “accurate knowledge of the world’s supply, day by day, month by month in and month out, from season to season, and year to year in spite of crop failures, revolutions, and other unpredictable occurrences.” (Paxton and Gallagher, 1939)They go on to say, “In the Butter-Nut Coffee you drink today there is sure to be coffee grown thousands of miles apart and from all, or almost all, of the eighteen countries that supply us. Next day, or a week from now, still another combination is necessary the distinctive flavor of Butter-Nut Coffee for you.” (Paxton and Gallagher, 1939) This reveals that the climate sensitivity of the coffee bean, the ever-increasing demand, and quality expectations of the consumer for the product forced Butter-Nut to uptake resources from around the globe.

The Butter-Nut Coffee commodity chain expanding into these foreign locations exemplifies how the coffee industry have dramatic environmental impacts on a global scale. The methods of cultivations represent the strongest influential factors that contributed to the coffee industry’s environmental effects. These methods vary in the intensity of deforestation which is directly linked to a change in the biodiversity and the release of carbon emissions into the earth’s atmosphere. The most profound differences between cultivation practices are apparent in the system management of the coffee farm landscapes. (Morris, 2013) Coffee farming locations around the globe vary in the how they control production, giving rise to a broad collection of landscapes. The coffee fields that are considered rustic denotes plantations that are completely covered with natural tree species that shroud the coffee plants in shade. Sun grown coffee represents the opposite side of the spectrum where there are little to no trees are present in the area of cultivation. Due to their small size, coffee plants store very little carbon. Plantations consisting of sun grown coffee, where the fields have almost no trees, create an ecosystem in which very low amounts of carbon are being taken out of the atmosphere by vegetation. One possible way to lower coffee’s carbon footprint, “is to store more carbon in the trees on the farm.” (Morris, 2013)

Therefore, shade grown coffee’s use of trees on the landscape offers environmental benefits by lowering the global levels of atmospheric carbon. Of the 18 coffee producing countries utilized by Butter-Nut, many were in Central America. In the article, “Paxton and Gallagher Company’s Coffee Train”, Mexico is listed as one of their main coffee producing countries. (Paxton & Gallagher's Company Coffee Train, 1901) Much research has been conducted comparing the shade and sun grown coffee’s influence on biodiversity in Mexico, which can make implications on Butter-Nut’s environmental impacts in the region. In his article Robert Rice comments on the landscapes of shade grown coffee and its effects on biodiversity stating, “It is the managed shade covered, essentially a biodiversity managed by the farmer, that in turn allows promotion and presence of an associated biodiversity.” (Morris, 2013) He goes on to refer to a study conducted in Chiapas, Mexico that compared biodiversity between the two coffee managing systems. The authors of the study concluded that “it is imperative to highlight the ecological function of shade farms, not only in providing refuge for native tree fauna, but also in preserving connectivity and gene flow processes essential for reforestation by native tree species.” (Morris, 2013)

Where habitat fragmentation can have inhibitory effects of species population growth, the studies provide evidence that more shade-grown coffee farms can be beneficial to the maintaining of species diversity among the surrounding native forests as well. The evidence for the effects of agroforestry systems and may be helpful in understanding how Butter-Nut coffee influenced its coffee producing regions. There tend to be trends that relate the size of the coffee farms and the management systems they utilize. Rice states that larger farms tend to use sun grown coffee because “less tending of the shade trees means that more time can be spent on tending to the coffee bushes.” (Morris, 2013) According to these trends, Butter-Nut, being a large company and producing massive amounts of coffee to meet the public demand, would have used sun grown coffee. Therefore, it is likely Butter-Nut coffee contributed to the loss of biodiversity, an increase in coffee’s carbon footprint, and habitat fragmentation.

Clearly, analysis of Omaha’s Butter-Nut Coffee commodity chain reveals the coffee industry’s dramatic effects on the global environment, which are proportional to the historical changes in consumption and production of the product. Coffee drinkers and, in the case of Butter-Nut, Omahans specifically, have been participating in an intricate process that has gained complexity over time. The story of commodification and consumption requires players that desire a product. Our examination of the process in which Butter-Nut acquired beans, imported them, and processed the final product shows how cities can have far-reaching effects on the global environment by requiring resources from increasingly further places. Coffee is a clear example of how high demand for a product changes the environment where it is produced, while creating a complex and competitive market for the final product. This is demonstrated by coffee growing fields in the tropics, and brands like Paxton & Gallagher’s line of Butter-Nut Coffee.

Grown in the “Bean Belt-” the area between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn - and shipped globally, coffee can be found in our stores, our homes, and in the factories that process beans. It is no surprise why coffee is popular. It’s flavors... the cultural significance… its mild addictiveness… but how it achieved such prominence is a fascinating story that connects the rise of cities with different environments. It is a tale of the Anthropocene. We are surrounded by evidence of that story, whether in the form of coffee cans on our shelves or the immense fields of coffee beans in distant countries. You drink that story with every sip of coffee. The Butter-Nut Coffee can represents Omaha’s place in that story. The commodity chain developed over the last 150 years to bring coffee into our homes and businesses speaks to dramatic changes the coffee industry has had on the global environment.

Coffee traveled long and far to end up in the roasters that supplied Butter-Nut Coffee. The bean was first described in writing to be a beneficial crop as early as 1000 CE by Avicenna of Bukhara (in modern-day Uzbekistan), and scholars have found evidence of widespread coffee drinking during the mid-15th century after it found its way to Mecca. From there, coffee traveled along trade routes and became an instant hit wherever it was available. Cafes became popular places to meet in 17th century Europe, and the beans were already being exported to America by 1668. (Luttinger and Dicum, 2006) A crop with such a global popularity does not enter our lives unnoticed. “Only a handful of consumer goods have fueled the passions of the public as much as coffee. [It] has inspired battlefields of economics, human rights, politics, and religion” while becoming a part of our everyday lives thanks to the chemical composition responsible for its habit-forming properties and enjoyable taste. (Luttinger and Dicum, 2006)

By the early 18th century, obsession with coffee expanded to the US. Coffee consumption was on par with tea domestically until the 1880s, when an influx of immigrants hoping to have the economic ability to purchase coffee began to settle in the US. (Morris, 2013) It was not a specific taste for coffee that the immigrants sought, but rather, they yearned for the financial agency to obtain coffee - something that could be done in America, as argued by coffee historian Jonathan Morris, PhD. Around this time, various manufacturers of coffee began to notice an uptick in demand of an already popular product and acted accordingly, importing increasing amounts of beans from source countries like Brazil. (Figure 1) Speaking on the early dramatic rise of coffee consumption in America, notable coffee historian Steven Topik describes how “consumption ballooned from under one pound [per capita] at independence to nine pounds in 1882,” leading to the US consuming one-fifth of the world’s coffee at this time. (Topik, 2013) Paxton & Gallagher as suppliers would ultimately create a coffee powerhouse in the Midwest during this popularity surge - and would be the first producer to sell coffee in tin cans, as opposed to loose beans, in the state of Nebraska. (Landale, 1945)

The story of coffee in Omaha began long after it was found that coffee beans could be stewed into an energizing elixir. Omaha businessmen William Paxton and Benjamin Gallagher enjoyed success across several industries and rose to prominence in the late nineteenth century thanks to their investments and ties to other prominent capitalist families like the Creightons. (NSHS, 2010) In 1879, the pair established a trading post that enjoyed success along the rail lines they helped to build, and by 1887 they were roasting beans for distribution on 10th and Jones streets in Omaha. (OWH. 1994)(Figure 2) The unique process used gas instead of coal to roast the imported green coffee faster, reducing the detrimental effects of prolonged heat exposure while still achieving the desired characteristics in an effort to preserve the freshness and flavor of the coffee. (OWH, 1915)

Paxton & Gallagher used their method as a unique selling point, bragging to audiences about how they spare no expense to produce the best product. “Gas roasting means something,” says an ad in an April 1915 printing of the Omaha-World Herald. “The Omaha Gas Company will tell you that we are the biggest gas consumers in the city. You can use your own judgment, for we certainly would not pay them over $500.00 a month for gas to roast our coffee if we could do it by using coal for $50.00 a month.” (OWH, 1915) This advertisement reveals to us the efforts that Paxton and Gallagher made in creating their product, while also showcasing their immense gas consumption. This braggadocio with respect to energy consumption is a trait of the Anthropocene, as it demonstrates the ideal of producing as much product as possible with little thought to possible impacts. Beans first arrived via railroads and were stored onsite. (OCCJ, 1936) After being fed through pneumatic tubes in 120 pound increments, the beans were dumped into one of several sixty-foot-long roasters. (The Spice Mill, 1911) After twenty minutes of roasting, the roasted and ground blend of coffee was then packaged in two pound red coffee cans vacuum-packed to preserve taste - a new development for coffee in the early 20th century that gave Paxton & Gallagher a marketable advantage. (The Spice Mill, 1911) These cans were emblazoned with “PAXTON GAS ROASTED COFFEE,” much like the first coffee can artifact from The Durham Museum, which can lead one to reasonably conclude that this can was created around 1915. (Figure 3)

This can lands a spot in The Durham thanks to the large role that Paxton & Gallagher had in shaping the Omaha economy through their roastery, among other ventures. Their coffee brand would only grow for most of the 20th century. Shortly after the production of this can, Paxton & Gallagher launched the Butter-Nut line of foods, which included coffee. Named after a tree nut, this rebranding was an attempt to describe their sweet-smelling product and launch a successful effort that would increase its reach to other states. The number of employees at the roastery on 10th street grew with increased demand, doubling in size to 150 between 1939 and 1942. (Landale, 1945) Butter-Nut directly impacted the economic scene in Omaha by employing a steady, local workforce.

As demand for coffee increased and Butter-Nut’s sales grew, competitors began eyeing the corporation. In 1958 the coffee line was bought by Clark and Gilbert Swanson, and was then acquired by Coca-Cola in 1964 thanks to a stock transition worth $30 million. (Coca-Cola, 1969) It is during this time under Coke that the second coffee can was produced - likely in the late 1960s.(Figure 4) Its design changes reflect ideals of modernization that were driven by the commercial consolidations that produced the can. With company structures changing through acquisitions and time, the can designs were periodically updated to appeal to consumers. In 1989, Butter-Nut was sold to an investor working for Maryland Club Foods, and later that year was finally sold to Procter & Gamble, where a Butter-Nut variant of Folger’s was produced. (United Press International, 1989) The flavor was discontinued and Folger’s was sold to Smucker’s, which accounts for 69% of today’s coffee sales along with the remaining “Big Five” coffee producers. (Morris, 2013) Butter-Nut Coffee distinguished itself from the competing brands of its time through its unique taste and aroma.

As its popularity grew exponentially, the Butter-Nut Coffee swiftly established itself as a common household brand and found its way into millions of homes across the Midwest. Butter-Nut faced two primary obstacles that blocked the growing company’s path in maximizing their profit margins, both of which were derived from the biological nature of the coffee bean itself. One limitation is the fact that coffee beans will only grow in tropical climates that exist in certain geographical locations. The collective growing sites of coffee around the world is known as the coffee belt which, “spans the globe along the equator, with cultivation in Central and South America; the Caribbean; Africa; the Middle East; and Asia. Brazil is now the world’s largest coffee-producing country.” (Scott, 2015) (Figure 5) While Butter-Nut could process and distribute its product in North America, they had to import the coffee beans, “from the 18 producing countries in Central America, South America, and Africa.” (OWH, 1959)

The second obstacle the company encountered was the unpredictable events affecting coffee yields from Butter-Nut’s eighteen producing countries. The motivation to overcome this challenge is due to the rising demand and the consumer’s expectation of the product’s quality which both had to be met in order to maintain the company’s gain in capital. This is evident in the Seventy Fifth Anniversary Cook Book, produced by the Paxton and Gallagher company in 1939. (Figure 6) When describing the origin of their coffee they state that maintaining adequate amounts of their product, “accurate knowledge of the world’s supply, day by day, month by month in and month out, from season to season, and year to year in spite of crop failures, revolutions, and other unpredictable occurrences.” (Paxton and Gallagher, 1939)They go on to say, “In the Butter-Nut Coffee you drink today there is sure to be coffee grown thousands of miles apart and from all, or almost all, of the eighteen countries that supply us. Next day, or a week from now, still another combination is necessary the distinctive flavor of Butter-Nut Coffee for you.” (Paxton and Gallagher, 1939) This reveals that the climate sensitivity of the coffee bean, the ever-increasing demand, and quality expectations of the consumer for the product forced Butter-Nut to uptake resources from around the globe.

The Butter-Nut Coffee commodity chain expanding into these foreign locations exemplifies how the coffee industry have dramatic environmental impacts on a global scale. The methods of cultivations represent the strongest influential factors that contributed to the coffee industry’s environmental effects. These methods vary in the intensity of deforestation which is directly linked to a change in the biodiversity and the release of carbon emissions into the earth’s atmosphere. The most profound differences between cultivation practices are apparent in the system management of the coffee farm landscapes. (Morris, 2013) Coffee farming locations around the globe vary in the how they control production, giving rise to a broad collection of landscapes. The coffee fields that are considered rustic denotes plantations that are completely covered with natural tree species that shroud the coffee plants in shade. Sun grown coffee represents the opposite side of the spectrum where there are little to no trees are present in the area of cultivation. Due to their small size, coffee plants store very little carbon. Plantations consisting of sun grown coffee, where the fields have almost no trees, create an ecosystem in which very low amounts of carbon are being taken out of the atmosphere by vegetation. One possible way to lower coffee’s carbon footprint, “is to store more carbon in the trees on the farm.” (Morris, 2013)

Therefore, shade grown coffee’s use of trees on the landscape offers environmental benefits by lowering the global levels of atmospheric carbon. Of the 18 coffee producing countries utilized by Butter-Nut, many were in Central America. In the article, “Paxton and Gallagher Company’s Coffee Train”, Mexico is listed as one of their main coffee producing countries. (Paxton & Gallagher's Company Coffee Train, 1901) Much research has been conducted comparing the shade and sun grown coffee’s influence on biodiversity in Mexico, which can make implications on Butter-Nut’s environmental impacts in the region. In his article Robert Rice comments on the landscapes of shade grown coffee and its effects on biodiversity stating, “It is the managed shade covered, essentially a biodiversity managed by the farmer, that in turn allows promotion and presence of an associated biodiversity.” (Morris, 2013) He goes on to refer to a study conducted in Chiapas, Mexico that compared biodiversity between the two coffee managing systems. The authors of the study concluded that “it is imperative to highlight the ecological function of shade farms, not only in providing refuge for native tree fauna, but also in preserving connectivity and gene flow processes essential for reforestation by native tree species.” (Morris, 2013)

Where habitat fragmentation can have inhibitory effects of species population growth, the studies provide evidence that more shade-grown coffee farms can be beneficial to the maintaining of species diversity among the surrounding native forests as well. The evidence for the effects of agroforestry systems and may be helpful in understanding how Butter-Nut coffee influenced its coffee producing regions. There tend to be trends that relate the size of the coffee farms and the management systems they utilize. Rice states that larger farms tend to use sun grown coffee because “less tending of the shade trees means that more time can be spent on tending to the coffee bushes.” (Morris, 2013) According to these trends, Butter-Nut, being a large company and producing massive amounts of coffee to meet the public demand, would have used sun grown coffee. Therefore, it is likely Butter-Nut coffee contributed to the loss of biodiversity, an increase in coffee’s carbon footprint, and habitat fragmentation.

Clearly, analysis of Omaha’s Butter-Nut Coffee commodity chain reveals the coffee industry’s dramatic effects on the global environment, which are proportional to the historical changes in consumption and production of the product. Coffee drinkers and, in the case of Butter-Nut, Omahans specifically, have been participating in an intricate process that has gained complexity over time. The story of commodification and consumption requires players that desire a product. Our examination of the process in which Butter-Nut acquired beans, imported them, and processed the final product shows how cities can have far-reaching effects on the global environment by requiring resources from increasingly further places. Coffee is a clear example of how high demand for a product changes the environment where it is produced, while creating a complex and competitive market for the final product. This is demonstrated by coffee growing fields in the tropics, and brands like Paxton & Gallagher’s line of Butter-Nut Coffee.

Creator

Trevor Schlecht

Zach Tapia

Zach Tapia

Source

Baker, Peter S. “Coffee as a Global System.” Coffee: A Comprehensive Guide to the Bean, the

Beverage, and the Industry, (2013) 26-29

"Butter Nut Coffee Roasted Far From Growing Fields." Omaha Chamber of Commerce Journal,

May 1936, 4-5.

Coca-Cola Company Foods Division. "The Coffee Processing Story at the Butter Nut

Coffee Plant." News release, Houston, TX, May 1969. The Coca-Cola Company.

"Coffee-Roasting Equipment of Paxton & Gallagher." The Spice Mill, Vol. 34 No. 1, January

1911, 359.

"Ex-Butter-Nut Workers Brew Omaha Reunion." Omaha World-Herald , October 8 , 1994.

Landale, Ted . "Coffee Business Cures Its Own Wartime Headache ." Omaha World-Herald ,

January 21 , 1945.

Landale, Ted . "Oldest or Youngest ." Omaha World-Herald , March 1 , 1959.

Luttinger, Nina, and Gregory Dicum. The Coffee Book: Anatomy of an Industry from crop to the

last drop. New York: New Press, 2006.

"Maryland Club Foods completes coffee acquisition." United Press International, February 1,

1989.

Michon, Scott. "Climate and Coffee." Climate.gov. June 19, 2015. Accessed November 7, 2017.

https://www.climate.gov/news-features/climate-and/climate-coffee.

Morris, Jonathan. “Coffee, a Condensed History”. Coffee: A Comprehensive Guide to the Bean,

the Beverage, and the Industry. Maryland: Rowman and Littleton, 2013. 215-224.

"Notable Nebraskans." Nebraska State Historical Society. June 3, 2010.

"Paxton & Gallagher's Company Coffee Train." September 1 , 1901.

Paxton and Gallagher Co. Seventy Fifth Anniversary Cook Book. Paxton and Gallagher, 1939

Rice, Robert. “Shade Coffee Farms and Biodiversity.” Coffee: A Comprehensive Guide to the Bean, the Beverage, and the Industry, (2013) 42-49

"To Our Dealers ." Omaha World-Herald , April 24 , 1915.

Topik, Steven. “Why Americans Drink Coffee”. Coffee: A Comprehensive Guide to the Bean, the

Beverage, and the Industry. Maryland: Rowman and Littleton, 2013. 234-244.

Beverage, and the Industry, (2013) 26-29

"Butter Nut Coffee Roasted Far From Growing Fields." Omaha Chamber of Commerce Journal,

May 1936, 4-5.

Coca-Cola Company Foods Division. "The Coffee Processing Story at the Butter Nut

Coffee Plant." News release, Houston, TX, May 1969. The Coca-Cola Company.

"Coffee-Roasting Equipment of Paxton & Gallagher." The Spice Mill, Vol. 34 No. 1, January

1911, 359.

"Ex-Butter-Nut Workers Brew Omaha Reunion." Omaha World-Herald , October 8 , 1994.

Landale, Ted . "Coffee Business Cures Its Own Wartime Headache ." Omaha World-Herald ,

January 21 , 1945.

Landale, Ted . "Oldest or Youngest ." Omaha World-Herald , March 1 , 1959.

Luttinger, Nina, and Gregory Dicum. The Coffee Book: Anatomy of an Industry from crop to the

last drop. New York: New Press, 2006.

"Maryland Club Foods completes coffee acquisition." United Press International, February 1,

1989.

Michon, Scott. "Climate and Coffee." Climate.gov. June 19, 2015. Accessed November 7, 2017.

https://www.climate.gov/news-features/climate-and/climate-coffee.

Morris, Jonathan. “Coffee, a Condensed History”. Coffee: A Comprehensive Guide to the Bean,

the Beverage, and the Industry. Maryland: Rowman and Littleton, 2013. 215-224.

"Notable Nebraskans." Nebraska State Historical Society. June 3, 2010.

"Paxton & Gallagher's Company Coffee Train." September 1 , 1901.

Paxton and Gallagher Co. Seventy Fifth Anniversary Cook Book. Paxton and Gallagher, 1939

Rice, Robert. “Shade Coffee Farms and Biodiversity.” Coffee: A Comprehensive Guide to the Bean, the Beverage, and the Industry, (2013) 42-49

"To Our Dealers ." Omaha World-Herald , April 24 , 1915.

Topik, Steven. “Why Americans Drink Coffee”. Coffee: A Comprehensive Guide to the Bean, the

Beverage, and the Industry. Maryland: Rowman and Littleton, 2013. 234-244.

Collection

Citation

Trevor Schlecht

Zach Tapia, “Coffee Cans,” Omaha in the Anthropocene, accessed April 18, 2024, https://steppingintothemap.com/anthropocene/items/show/3.

Embed

Copy the code below into your web page