Transcontinental Telegraph Wire

Title

Transcontinental Telegraph Wire

Subject

In 1961, Western Union gifted this part of the transcontinental telegraph line to Creighton University to commemorate the Creightons' contributions the city of Omaha. Invented in 1836 during the second industrial revolution, the telegraph changed communication forever. Telegraphs are messages sent over wires by electricity. The transcontinental telegraph united the country from coast to coast, and eventually, telegraph lines crossed oceans. Every new telegraph cable built connected businesses to new markets and helped change the landscape it passed through. Plains became feeding areas; green woods turned to timber yards; and mountain sides gave way to coal mines. These changes depended upon rapid, effective communication provided by the telegraph. (Western Union Telegraph Company sent Edward Creighton to survey the Omaha area and determine the best route of installation. His wealth and business experience helped grow and shape the city, and allowed his wife Lucretia to fund Creighton University.)

The transcontinental telegraph showed the growth and enhancement of global telecommunications. This includes communication by means of cable, telegraph, telephone, or broadcasting. Expansion of telegraph networks mirrors today expansion of communication networks. Edward Creighton was brought to Omaha by the telegraph, which allowed him to earn his fortune. His wife Lucretia later used a portion of his earnings to fund Creighton University.

The transcontinental telegraph showed the growth and enhancement of global telecommunications. This includes communication by means of cable, telegraph, telephone, or broadcasting. Expansion of telegraph networks mirrors today expansion of communication networks. Edward Creighton was brought to Omaha by the telegraph, which allowed him to earn his fortune. His wife Lucretia later used a portion of his earnings to fund Creighton University.

Description

Before the telegraph, communicating across distances meant waiting for letters delivered by horses, boats, and trains, that often took days or weeks to reach their destination. Today, we cannot imagine life without instant communication. The invention of the telegraph in 1836 during the second industrial revolution allowed immediate transmission of messages, and suddenly business transactions could be made from across the country, increasing trade, globalization, and the accumulation of capital - all of which had dramatic environmental consequences. These connections in Omaha were directly linked to changes in telecommunication developing on a global scale - a telegraph could be sent from anywhere in the country and make its way across the globe in minutes.

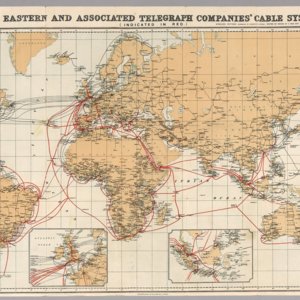

When considering the growth of Omaha, the telegraph and its implication for the area cannot be left out - with a direct connection to Edward Creighton and Omaha, the telegraph’s impact is undeniable. (Figure 1) On a larger level, the telegraph not only connected the United States from coast to coast, but also to the rest of the globe. (Figure 2) The telegraph played an important role in the telecommunication revolution of the second industrial revolution and the mass globalization that stemmed from it, and continues to be relevant in the discussion of globalization’s effect on the environment. Globalization has resulted in an increased demand for goods and competition, ultimately leading to exploitation of the environment’s natural resources. The telegraph, then, and it’s connection to the Anthropocene, is beyond doubt.

For the invention of the telegraph, Samuel F. B. Morse is to thank. Morse’s initial telegraph was crudely composed of parts from his painting studio. The first part of the apparatus recorded messages. Made of old canvas stretchers nailed against the side of a table, with a bar attached to an electromagnet hung across the middle of the frame. A lever stretched from the top of the frame, holding a magnet, its base holding a pencil onto a roll of paper. The second part of the apparatus transmitted messages, and consisted of a long horizontal rod with a saw-toothed type arranged in a deep slot at the top. The type was arranged in a way that opened and closed an electrical circuit according to a code pattern received as dots and lines as the pencil moved up and down, marking the moving paper. (Thompson, 1947)

Galvanic batteries with 10-30 cylinders were used to power the telegraph after its installation. The cylinders were zinc with a thin plating of copper or platina, and placed in a glass vessel containing weak sulfuric acid. Operators placed a porous earthenware jar placed inside the zinc cylinder, containing a platina plate and weak nitric acid. To create a circuit copper wire was attached to the end of a platina plate to the zinc cylinder, and on the final cylinder from the platina to a metallic key on a pivot used by the operator. Pressing this key lifts the opposite end breaking the circuit, causing the pencil on the receiving apparatus to lower and transcribe the message. (Scientific American, 1851) Cables carrying messages were made of seven copper wires tinned over, and sheathed with natural latex or felted tape, and encased in india rubber. (Scientific American, 1871)

Morse was motivated to improve communication after missing his wife’s funeral due to slow communication methods. To keep his mind off grief, Morse attended a series of lectures by James Freeman Dana. Morse’ and interest in electricity led Dana to stop by Morse’ studio often, where they would further discuss the applications of electricity. The idea of the telegraph was born on Morse’s return from Europe in 1832, during a discussion about electromagnetism. Morse saw no reason why electricity could not serve as a medium across which, “intelligence might not be instantaneously transmitted by electricity to any distance.” Morse completed his first telegraph apparatus and numerical code to represent the alphabet in 1836. (Thompson, 1947)

Professor Leonard D. Gale of New York University helped improve the battery and electromagnet, increasing transmission from 40ft to 10 miles of wire arrange around Gale’s lecture room. (Thompson, 1947) Alfred Vail, graduate student and owner of an iron and brass works in New Jersey, heard of Morse’ invention and agreed to pay for the construction of telegraph instruments for a demonstration before a Congressional committee in January 1838. (Thompson, 1947) Morse took on Gale and Vail as partners. After successful exhibitions in the US and Europe, the American Senate signed the Telegraph Bill on March 3, 1843. The bill provided $30,000 (worth $918,183 today) for constructing an experimental telegraph line from Washington to Baltimore. Representative Cave Johnson of Tennessee felt Congress was doing much to encourage science, and he, “did not wish to see the science of mesmerism overlooked.” The majority of members agreed that allowing further experiments would be beneficial. (Thompson, 1947) This was the first step in the process of building the first transcontinental telegraph line. The ambition of this project was to connect the east and west coasts.

Without Morse’ invention and persistence Omaha would not be the city it is today. When the installation reached Omaha, it was a small city just starting out. Western Union Telegraph Company sent Edward Creighton to survey to surrounding area and determine the best route of installation. His wealth and experience helped grow and shape the city. To commemorate the Creighton family’s contributions, the city of Omaha presented this piece of telegraph wire to Creighton University in 1961.

At the age of fourteen Creighton began his entrepreneurial career as a cart boy delivering goods. When he was eighteen years old, his father gave him a wagon and team of horses, which he used to haul freight long distance within his home state of Ohio. He later expanded his business to building roads, grading city streets, and preparing roadbeds for railroad tracks. This experience made him ideal for working on the transcontinental telegraph. Through hard work Creighton earned the respect of his peers, and overcame the stereotypes of being Irish and Catholic. After seeing two Irish-Americans installing a line, Creighton shifted his business focus and began supplying and transporting lumber for the poles. He later secured contracts for grading the land, and within a year was supervising construction of multiple lines. (Mihelich, 2006)

Creighton began working for the Western Union Telegraph Company and was chosen to survey the western plains for the proposed transcontinental line and provide it with supplies. (Mihelich, 2006; Zornow, 1950) Creighton and his younger brother John moved to Omaha, Nebraska in 1856 to sell their equipment, and head to the new town of Omaha, Nebraska to restart his businesses. The Panic of 1857 and the Civil War stalled his plans to install telegraph lines to the west coast and caused the economy to plunge, however, Edward still made money by becoming a creditor. (Mihelich, 2006)

When the telegraph reached California on October 23, 1861 Edward returned to Omaha and became the general superintendent of the Pacific Telegraph Company. Using the nineteenth century business device of watered stock and artificially inflating the value, Edward and other directors profited more than they should have. Spending only $147,000 of the $400,000 subsidy they received to build a line, then issuing $1 million in stock which directors paid significantly less for. In 1864 Western Union absorbed Pacific Telegraph, and despite the initially inflated value, the actual value of stock rose. Edward sold one third of his stock for 8x the price he paid, receiving $85,000 (approximately $1.3 million today). (Michelich, 2006; Inflation Calculator)

Mounting capital allowed Edward to create a freighting company, which took goods from Omaha to Salt Lake City to trade with the Mormon community there, then to the goldfields of Montana. Before the Platte River Bridge Company he started could take off, Union Pacific laid 305 miles of track west of Omaha. Changing his business, Edward began to transport goods between gaps in the railroad. Herds of draft animals did the grunt work for this business requiring arrangement of grazing rights until the Homestead Act of 1862. Large amounts of pasture west of the Missouri River became available, allowing Edward to claim thousands of acres so his herds to eat for free. Grazing extra animals to sell further increased profits. (Mihelich, 2006)

Edward Creighton played an active role in all his businesses until November 3, 1874 when he collapsed in his office. Never regaining consciousness, he died two days later. Without a will, his wife Lucretia and brother John inventoried and administered her husband’s estate. Lucretia became ill and died in 1876, leaving in her will $100,000 for the founding of a, “Creighton College as a testimony to her late husband's virtues and her affection to his memory.” She did this for Edward because he wanted to found an institute of higher learning, but never got the chance. (Mihelich, 2006)

Throughout the duration of man’s time on earth, communication has continued to evolve. The invention of the telegraph initiated a shift from communication by means of letters that took days to weeks to be delivered to messages that could be delivered and received in a matter of seconds or minutes. The telegraph kickstarted the telecommunications revolution of the Second Industrial Revolution and from it stemmed a rapid advance in new forms of technology that allowed for faster and easier communication, which of course, meant increased connectedness felt around the globe. The second industrial revolution, also referred to as the “Technological Revolution” is the time period during which the telegraph was brought to life. Beginning in 1870, the second industrial revolution was a time of great economic and industrial growth in America after the Civil War that gave way to numerous advances in different technologies, including the telegraph and railroad.

Prior to the transatlantic cable connecting London and New York, it took three weeks for letters to travel across the ocean. Throughout Europe, the telegraph was also revolutionizing communication, with major cities serving as points of communication: “London was a major international communications node, as were Paris and Berlin. Perhaps somewhat surprisingly so too were Vienna and Budapest.” (EH.net) Investors often chose to do business within local markets at a known price instead of using information from a foreign market that was already a month old. The transatlantic cable cut down communication time to one day. Transaction prices were still accurate upon receipt and orders from foreign markets were able to be put in faster. Foreign transactions added came shipping costs, so cheaper goods did not always mean lower total costs. (Esty and Ivanova, 2003) To summarize the effects of the telegraph on a global scale: “By 1900, communication times converged and no longer reflected geography, presumably suggesting that globalization was entering a new phase.” (EH.net)

History has shown that globalization often comes at a cost to the environment. Globalization has led to an increased consumption of products and competition within various industries. Lower environmental standards are a consequence of increased competition, as countries competing for global trade opportunities face pressure to lower prices, which often time results in detrimental exploitation of the environment. A higher demand to export products means more of a reason to push natural resources to their limit if it maximizes production. (Esty and Ivanova, 2003)

An increased demand for goods to be imported and exported around the world has requires transportation. Food is an obvious example: “Globalization has also led to an increase in the transportation of raw materials and food from one place to another. Earlier, people used to consume locally-grown food, but with globalization, people consume products that have been developed in foreign countries." (Esty and Ivanova, 2003) Such a high demand for goods to be transported around the globe puts a strain on non-renewable energy sources, and the environment ultimately suffers. “The gases that are emitted from the aircraft have led to the depletion of the ozone layer apart from increasing the greenhouse effect. The industrial waste that is generated as a result of production has been laden on ships and dumped in oceans.” Overall, “production, transportation and use of consumer goods results in more waste, pollution and fuel use.” (McAusland, 2008)

Apart from the effect of the telegraph on the manner in which individual businesses operated, capitalism itself owes much to the telegraph wire, for without the means to communicate on a transcontinental level, the huge web of business practices that we know to exist today as capitalism would not be so. Referred to as the “‘great item with commercial men,’” the ability to send seemingly instant messages by means of the telegraph greatly influenced the “acquisition, exchange, and circulation of specialized economic information by major-center businessmen.” (Pred, 1980) Bankers, manufacturers and other businesses used the telegraph to finalize buying or selling arrangements, and the Stock Market relied on the instant communication made possible by the telegraph to follow conditions of supply and demand. The telegraph meant that trade could occur more efficiently on a larger scale, impacting the level of speed at which negotiations could be made: “the telegraph not only affected when and where business opportunities were exploited, but, since they were performed in minutes and hours rather than days and weeks, they affected the pace at which capital could circulate, turn over, and accumulate.” (Pred, 1980)

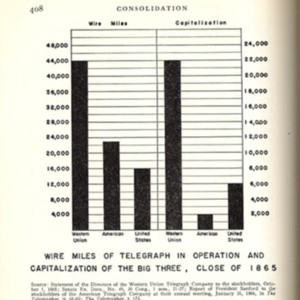

The telegraph changed the nature of business interactions in the nineteenth century, but that power was controlled by a relatively limited number of corporations. Initially, a number of telegraph companies obstructed the telecommunications infrastructure and controlled (and profited) from its operation. This gave way to the telegraph monopoly of the Western Union during the last half of the 19th century. Western Union absorbed numerous smaller companies, as shown in the illustration on the right, and rose “in two short decades to become the largest and most powerful corporation in the United States.” (Nonnenmacher, 2001)

In the case of Western Union, more wire miles meant more capital - the connection between the telegraph and capitalism is undeniable. (Figure 3) Due to its large contribution to the acceleration of capitalism and globalization, the telegraph wire earns its place within the Anthropocene, even if its own impact as a material object on the environment is in some ways indirect. The telegraph is a representation of capitalism, and capitalism has been seen to have negative impacts on the Earth System.

While the telegraph wire is no longer in use - the last message was transmitted in 2006 - modern day communication methods have the telegraph to thank for their existence today. (Thompson, 1947) The telegraph was the first form of instant messaging, a concept that is an integral part of everyday life. The implications of the wire’s impact on capitalism and globalization are still felt today, as the connection of the world and efficiency of the business world relies on rapid communication on a global level. The telegraph wire, due to its contributions to globalization growth of capitalism is a representation of human impact on the Earth System. Globalization has contributed to an increase in consumerism, which has resulted in negative effects on the environment such as exploitation of resources from the environment and due to a demand for products and transportation. The way businesses conduct trade was changed by the telegraph, as was the way humans communicate in general. The segment of the transcontinental telegraph line mounted on a plaque house at Creighton University is a clear representation of humankind’s impact on the earth, and for that reason, the telegraph earns itself a place in the Anthropocene.

When considering the growth of Omaha, the telegraph and its implication for the area cannot be left out - with a direct connection to Edward Creighton and Omaha, the telegraph’s impact is undeniable. (Figure 1) On a larger level, the telegraph not only connected the United States from coast to coast, but also to the rest of the globe. (Figure 2) The telegraph played an important role in the telecommunication revolution of the second industrial revolution and the mass globalization that stemmed from it, and continues to be relevant in the discussion of globalization’s effect on the environment. Globalization has resulted in an increased demand for goods and competition, ultimately leading to exploitation of the environment’s natural resources. The telegraph, then, and it’s connection to the Anthropocene, is beyond doubt.

For the invention of the telegraph, Samuel F. B. Morse is to thank. Morse’s initial telegraph was crudely composed of parts from his painting studio. The first part of the apparatus recorded messages. Made of old canvas stretchers nailed against the side of a table, with a bar attached to an electromagnet hung across the middle of the frame. A lever stretched from the top of the frame, holding a magnet, its base holding a pencil onto a roll of paper. The second part of the apparatus transmitted messages, and consisted of a long horizontal rod with a saw-toothed type arranged in a deep slot at the top. The type was arranged in a way that opened and closed an electrical circuit according to a code pattern received as dots and lines as the pencil moved up and down, marking the moving paper. (Thompson, 1947)

Galvanic batteries with 10-30 cylinders were used to power the telegraph after its installation. The cylinders were zinc with a thin plating of copper or platina, and placed in a glass vessel containing weak sulfuric acid. Operators placed a porous earthenware jar placed inside the zinc cylinder, containing a platina plate and weak nitric acid. To create a circuit copper wire was attached to the end of a platina plate to the zinc cylinder, and on the final cylinder from the platina to a metallic key on a pivot used by the operator. Pressing this key lifts the opposite end breaking the circuit, causing the pencil on the receiving apparatus to lower and transcribe the message. (Scientific American, 1851) Cables carrying messages were made of seven copper wires tinned over, and sheathed with natural latex or felted tape, and encased in india rubber. (Scientific American, 1871)

Morse was motivated to improve communication after missing his wife’s funeral due to slow communication methods. To keep his mind off grief, Morse attended a series of lectures by James Freeman Dana. Morse’ and interest in electricity led Dana to stop by Morse’ studio often, where they would further discuss the applications of electricity. The idea of the telegraph was born on Morse’s return from Europe in 1832, during a discussion about electromagnetism. Morse saw no reason why electricity could not serve as a medium across which, “intelligence might not be instantaneously transmitted by electricity to any distance.” Morse completed his first telegraph apparatus and numerical code to represent the alphabet in 1836. (Thompson, 1947)

Professor Leonard D. Gale of New York University helped improve the battery and electromagnet, increasing transmission from 40ft to 10 miles of wire arrange around Gale’s lecture room. (Thompson, 1947) Alfred Vail, graduate student and owner of an iron and brass works in New Jersey, heard of Morse’ invention and agreed to pay for the construction of telegraph instruments for a demonstration before a Congressional committee in January 1838. (Thompson, 1947) Morse took on Gale and Vail as partners. After successful exhibitions in the US and Europe, the American Senate signed the Telegraph Bill on March 3, 1843. The bill provided $30,000 (worth $918,183 today) for constructing an experimental telegraph line from Washington to Baltimore. Representative Cave Johnson of Tennessee felt Congress was doing much to encourage science, and he, “did not wish to see the science of mesmerism overlooked.” The majority of members agreed that allowing further experiments would be beneficial. (Thompson, 1947) This was the first step in the process of building the first transcontinental telegraph line. The ambition of this project was to connect the east and west coasts.

Without Morse’ invention and persistence Omaha would not be the city it is today. When the installation reached Omaha, it was a small city just starting out. Western Union Telegraph Company sent Edward Creighton to survey to surrounding area and determine the best route of installation. His wealth and experience helped grow and shape the city. To commemorate the Creighton family’s contributions, the city of Omaha presented this piece of telegraph wire to Creighton University in 1961.

At the age of fourteen Creighton began his entrepreneurial career as a cart boy delivering goods. When he was eighteen years old, his father gave him a wagon and team of horses, which he used to haul freight long distance within his home state of Ohio. He later expanded his business to building roads, grading city streets, and preparing roadbeds for railroad tracks. This experience made him ideal for working on the transcontinental telegraph. Through hard work Creighton earned the respect of his peers, and overcame the stereotypes of being Irish and Catholic. After seeing two Irish-Americans installing a line, Creighton shifted his business focus and began supplying and transporting lumber for the poles. He later secured contracts for grading the land, and within a year was supervising construction of multiple lines. (Mihelich, 2006)

Creighton began working for the Western Union Telegraph Company and was chosen to survey the western plains for the proposed transcontinental line and provide it with supplies. (Mihelich, 2006; Zornow, 1950) Creighton and his younger brother John moved to Omaha, Nebraska in 1856 to sell their equipment, and head to the new town of Omaha, Nebraska to restart his businesses. The Panic of 1857 and the Civil War stalled his plans to install telegraph lines to the west coast and caused the economy to plunge, however, Edward still made money by becoming a creditor. (Mihelich, 2006)

When the telegraph reached California on October 23, 1861 Edward returned to Omaha and became the general superintendent of the Pacific Telegraph Company. Using the nineteenth century business device of watered stock and artificially inflating the value, Edward and other directors profited more than they should have. Spending only $147,000 of the $400,000 subsidy they received to build a line, then issuing $1 million in stock which directors paid significantly less for. In 1864 Western Union absorbed Pacific Telegraph, and despite the initially inflated value, the actual value of stock rose. Edward sold one third of his stock for 8x the price he paid, receiving $85,000 (approximately $1.3 million today). (Michelich, 2006; Inflation Calculator)

Mounting capital allowed Edward to create a freighting company, which took goods from Omaha to Salt Lake City to trade with the Mormon community there, then to the goldfields of Montana. Before the Platte River Bridge Company he started could take off, Union Pacific laid 305 miles of track west of Omaha. Changing his business, Edward began to transport goods between gaps in the railroad. Herds of draft animals did the grunt work for this business requiring arrangement of grazing rights until the Homestead Act of 1862. Large amounts of pasture west of the Missouri River became available, allowing Edward to claim thousands of acres so his herds to eat for free. Grazing extra animals to sell further increased profits. (Mihelich, 2006)

Edward Creighton played an active role in all his businesses until November 3, 1874 when he collapsed in his office. Never regaining consciousness, he died two days later. Without a will, his wife Lucretia and brother John inventoried and administered her husband’s estate. Lucretia became ill and died in 1876, leaving in her will $100,000 for the founding of a, “Creighton College as a testimony to her late husband's virtues and her affection to his memory.” She did this for Edward because he wanted to found an institute of higher learning, but never got the chance. (Mihelich, 2006)

Throughout the duration of man’s time on earth, communication has continued to evolve. The invention of the telegraph initiated a shift from communication by means of letters that took days to weeks to be delivered to messages that could be delivered and received in a matter of seconds or minutes. The telegraph kickstarted the telecommunications revolution of the Second Industrial Revolution and from it stemmed a rapid advance in new forms of technology that allowed for faster and easier communication, which of course, meant increased connectedness felt around the globe. The second industrial revolution, also referred to as the “Technological Revolution” is the time period during which the telegraph was brought to life. Beginning in 1870, the second industrial revolution was a time of great economic and industrial growth in America after the Civil War that gave way to numerous advances in different technologies, including the telegraph and railroad.

Prior to the transatlantic cable connecting London and New York, it took three weeks for letters to travel across the ocean. Throughout Europe, the telegraph was also revolutionizing communication, with major cities serving as points of communication: “London was a major international communications node, as were Paris and Berlin. Perhaps somewhat surprisingly so too were Vienna and Budapest.” (EH.net) Investors often chose to do business within local markets at a known price instead of using information from a foreign market that was already a month old. The transatlantic cable cut down communication time to one day. Transaction prices were still accurate upon receipt and orders from foreign markets were able to be put in faster. Foreign transactions added came shipping costs, so cheaper goods did not always mean lower total costs. (Esty and Ivanova, 2003) To summarize the effects of the telegraph on a global scale: “By 1900, communication times converged and no longer reflected geography, presumably suggesting that globalization was entering a new phase.” (EH.net)

History has shown that globalization often comes at a cost to the environment. Globalization has led to an increased consumption of products and competition within various industries. Lower environmental standards are a consequence of increased competition, as countries competing for global trade opportunities face pressure to lower prices, which often time results in detrimental exploitation of the environment. A higher demand to export products means more of a reason to push natural resources to their limit if it maximizes production. (Esty and Ivanova, 2003)

An increased demand for goods to be imported and exported around the world has requires transportation. Food is an obvious example: “Globalization has also led to an increase in the transportation of raw materials and food from one place to another. Earlier, people used to consume locally-grown food, but with globalization, people consume products that have been developed in foreign countries." (Esty and Ivanova, 2003) Such a high demand for goods to be transported around the globe puts a strain on non-renewable energy sources, and the environment ultimately suffers. “The gases that are emitted from the aircraft have led to the depletion of the ozone layer apart from increasing the greenhouse effect. The industrial waste that is generated as a result of production has been laden on ships and dumped in oceans.” Overall, “production, transportation and use of consumer goods results in more waste, pollution and fuel use.” (McAusland, 2008)

Apart from the effect of the telegraph on the manner in which individual businesses operated, capitalism itself owes much to the telegraph wire, for without the means to communicate on a transcontinental level, the huge web of business practices that we know to exist today as capitalism would not be so. Referred to as the “‘great item with commercial men,’” the ability to send seemingly instant messages by means of the telegraph greatly influenced the “acquisition, exchange, and circulation of specialized economic information by major-center businessmen.” (Pred, 1980) Bankers, manufacturers and other businesses used the telegraph to finalize buying or selling arrangements, and the Stock Market relied on the instant communication made possible by the telegraph to follow conditions of supply and demand. The telegraph meant that trade could occur more efficiently on a larger scale, impacting the level of speed at which negotiations could be made: “the telegraph not only affected when and where business opportunities were exploited, but, since they were performed in minutes and hours rather than days and weeks, they affected the pace at which capital could circulate, turn over, and accumulate.” (Pred, 1980)

The telegraph changed the nature of business interactions in the nineteenth century, but that power was controlled by a relatively limited number of corporations. Initially, a number of telegraph companies obstructed the telecommunications infrastructure and controlled (and profited) from its operation. This gave way to the telegraph monopoly of the Western Union during the last half of the 19th century. Western Union absorbed numerous smaller companies, as shown in the illustration on the right, and rose “in two short decades to become the largest and most powerful corporation in the United States.” (Nonnenmacher, 2001)

In the case of Western Union, more wire miles meant more capital - the connection between the telegraph and capitalism is undeniable. (Figure 3) Due to its large contribution to the acceleration of capitalism and globalization, the telegraph wire earns its place within the Anthropocene, even if its own impact as a material object on the environment is in some ways indirect. The telegraph is a representation of capitalism, and capitalism has been seen to have negative impacts on the Earth System.

While the telegraph wire is no longer in use - the last message was transmitted in 2006 - modern day communication methods have the telegraph to thank for their existence today. (Thompson, 1947) The telegraph was the first form of instant messaging, a concept that is an integral part of everyday life. The implications of the wire’s impact on capitalism and globalization are still felt today, as the connection of the world and efficiency of the business world relies on rapid communication on a global level. The telegraph wire, due to its contributions to globalization growth of capitalism is a representation of human impact on the Earth System. Globalization has contributed to an increase in consumerism, which has resulted in negative effects on the environment such as exploitation of resources from the environment and due to a demand for products and transportation. The way businesses conduct trade was changed by the telegraph, as was the way humans communicate in general. The segment of the transcontinental telegraph line mounted on a plaque house at Creighton University is a clear representation of humankind’s impact on the earth, and for that reason, the telegraph earns itself a place in the Anthropocene.

Creator

Kassidy Smith

Lindzey Sánchez

Lindzey Sánchez

Source

Blondheim, Menahem. "Rehearsal for Media Regulation: Congress Versus the Telegraph-News Monopoly, 1866-1900." Federal Communications Law Journal 56, no. 2 (March 2004): 299-328. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed November 7, 2017).

Brown, Charles H. First Telegraph Line across the Continent. Lincoln, NE: Nebraska State Historical Society, 2011.

Esty, Daniel C. & Ivanova, Maria H. “Global Environmental Governance: the Post-Johannesburg Agenda” October 2003.

FinanceRef Inflation Calculator, Alioth Education. “$85,000 in 1864 → 2017 | Inflation Calculator.”, 15 Dec. 2017, http://www.in2013dollars.com/1864-dollars-in-2017?amount=85000.

Garbade, K., & Silber, W. (1978). Technology, Communication and the Performance of Financial Markets: 1840-1975. The Journal of Finance, 33(3), 819-832.

Lew, Byron. Connecting the Nineteenth-Century World: The Telegraph and Globalization. https://eh.net/book_reviews/5252/. Accessed 15 Dec. 2017.

"Manufacture of Telegraph Cables." Scientific American 25, no. 11 (1871): 165.

McAusland, Carol. “Global Forum on Transport and Environment in a Globalising World; Globalisation’s Direct and Indirect Effect on the Environment.” November 2008.

Mihelich, Dennis N. The History of Creighton University 1878-2003. Omaha, NE: Creighton University Press, 2006.

Moore, Jason W. “The Capitalocene, Part I: On the Nature and Origins of Our Ecological Crisis.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 44, no. 3 (May 4, 2017): 594–630.

NBC News. “STOP-Telegram Era over, Western Union Says.” Associated Press. February 2, 2006.

Nonnenmacher, Tomas. “History of the U.S. Telegraph Industry.” Edited by Robert Whaples. Economic History Encyclopedia. EH.Net Encyclopedia: Economic History Association, August 14, 2001. https://eh.net/encyclopedia/history-of-the-u-s-telegraph-industry/.

Pred, Allan. Urban Growth and City-Systems in the United States, 1840-1860. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1980.

Prescott, George B. History, Theory, and Practice of the Electric Telegraph. Boston, Ticknot and Fields, 1860.

Rumsey, David. “MEDIA INFORMATION.” The Eastern and Associated Telegraph Companies' Cable System, Eastern Associated Telegraph Companies, 1922.

Sandweiss, Martha A. “John Gast, American Progress, 1872.” Picturing United States History. Accessed October 8, 2017.

"THE AMERICAN ELECTRO MAGNETIC TELEGRAPH." Scientific American 6, no. 27 (1851): 211.

Thompson, Robert L. Wiring a Continent. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1947.

Zornow, William Frank. "Jeptha H. Wade in California: Beginning the Transcontinental Telegraph." California Historical Society Quarterly 29, no. 4 (1950): 345-56.

Brown, Charles H. First Telegraph Line across the Continent. Lincoln, NE: Nebraska State Historical Society, 2011.

Esty, Daniel C. & Ivanova, Maria H. “Global Environmental Governance: the Post-Johannesburg Agenda” October 2003.

FinanceRef Inflation Calculator, Alioth Education. “$85,000 in 1864 → 2017 | Inflation Calculator.”, 15 Dec. 2017, http://www.in2013dollars.com/1864-dollars-in-2017?amount=85000.

Garbade, K., & Silber, W. (1978). Technology, Communication and the Performance of Financial Markets: 1840-1975. The Journal of Finance, 33(3), 819-832.

Lew, Byron. Connecting the Nineteenth-Century World: The Telegraph and Globalization. https://eh.net/book_reviews/5252/. Accessed 15 Dec. 2017.

"Manufacture of Telegraph Cables." Scientific American 25, no. 11 (1871): 165.

McAusland, Carol. “Global Forum on Transport and Environment in a Globalising World; Globalisation’s Direct and Indirect Effect on the Environment.” November 2008.

Mihelich, Dennis N. The History of Creighton University 1878-2003. Omaha, NE: Creighton University Press, 2006.

Moore, Jason W. “The Capitalocene, Part I: On the Nature and Origins of Our Ecological Crisis.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 44, no. 3 (May 4, 2017): 594–630.

NBC News. “STOP-Telegram Era over, Western Union Says.” Associated Press. February 2, 2006.

Nonnenmacher, Tomas. “History of the U.S. Telegraph Industry.” Edited by Robert Whaples. Economic History Encyclopedia. EH.Net Encyclopedia: Economic History Association, August 14, 2001. https://eh.net/encyclopedia/history-of-the-u-s-telegraph-industry/.

Pred, Allan. Urban Growth and City-Systems in the United States, 1840-1860. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1980.

Prescott, George B. History, Theory, and Practice of the Electric Telegraph. Boston, Ticknot and Fields, 1860.

Rumsey, David. “MEDIA INFORMATION.” The Eastern and Associated Telegraph Companies' Cable System, Eastern Associated Telegraph Companies, 1922.

Sandweiss, Martha A. “John Gast, American Progress, 1872.” Picturing United States History. Accessed October 8, 2017.

"THE AMERICAN ELECTRO MAGNETIC TELEGRAPH." Scientific American 6, no. 27 (1851): 211.

Thompson, Robert L. Wiring a Continent. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1947.

Zornow, William Frank. "Jeptha H. Wade in California: Beginning the Transcontinental Telegraph." California Historical Society Quarterly 29, no. 4 (1950): 345-56.

Collection

Citation

Kassidy Smith

Lindzey Sánchez, “Transcontinental Telegraph Wire,” Omaha in the Anthropocene, accessed April 19, 2024, https://steppingintothemap.com/anthropocene/items/show/4.

Embed

Copy the code below into your web page