Arrowheads

Title

Subject

Description

The Anthropocene is a new age defined by a changing environment, due to the presence of human action. Anthropocene discourse is largely Eurocentric, privileging changes wrought by European Empires, the expansion of global capital, or industrial transformations of the environment (Carrington, 2016). Global modifications of the environment have a deeper lineage, however. One such lineage is the use of Arrowheads and other tools by native American tribes. Arrowheads are an important artifact for many Native American tribes, including the Omaha tribe. Arrowheads are important in Omaha’s environmental history because they represent pre-Columbian management of the Plains landscape. These arrowheads link Omaha’s environmental history to the global history of the Anthropocene because they represent the changes produced by human hunting. The peoples of the Plains used projectiles and fire mold the environment to their needs. Although distinctly American, they point to the larger implications of these tools on global environments.

The territory of Nebraska was home to diverse peoples long before the arrival of Europeans. The city of Omaha takes its name from the Omaha tribe who originally migrated west from modern Ohio (Wakeley, 1917). Originally, they were mainly hunters and farmers, then they took part in fur trading, and eventually came under the control of their powerful allies, the Pawnee tribe (Fletcher, 2013). During the tribe’s history they are noted to have faced hardships from the enemies of the Pawnee tribe, who were the Sioux tribe. They also faced hardships from smallpox and other disease. From war and disease, they had a population of under 300 in the early 1800s, from almost 3,000 a few decades earlier (Legends of America - The Omaha Indians).

The arrowheads were used for hunting by most indigenous people who lived on the Great Plains of North America, like the Omaha. Arrowheads are made in a variety of shapes, most often based on the region in which they were made. Based on the size and color of the arrowheads presented at The Durham Museum (Figure I), our arrowheads are most likely Samantha Arrows, which are primarily found in the Northern Plains of the United States (Samantha Arrowhead). Arrowheads are historically important because many tribes were migratory, which required that they find ways to carry their belongings and possessions with them. They often camped near rivers where they hunted for bison and found edible plants in the spring (Fagan, 1994). These indigenous people used a wide variety of materials to produce arrowheads. Obsidian, for example, was a volcanic glass found in the Rocky Mountains. Chert, a crystalline quartz, had razor-sharp edges which was also used to make arrowheads. Antler was also used to make arrowheads when suitable rock material wasn’t available. Some arrowheads were also reusable. Analysis from the Gila River in Arizona found that some arrow points were used to hunt large animals and they could be retrieved and used again while other unnotched points were only used one time and were usually used to kill people (Loendorf, 2015). This gives more context behind how the arrowheads were used. Most often though, these Indigenous people of the plains found use for the arrowheads in hunting, specifically for bison.

Hunting was integral to Native American culture and it tied Plains peoples to the land in diverse material and spiritual ways. Anthropologist David Lewis argues that Plain peoples built relationships with the land that transcended settlement; relationships that proved central to their identities (Lewis, 1995). Perhaps due to this close connection to the land, they used the environment as tools for many purposes. They planted many types of crops to feed themselves and their animals, they used the skin of hunted animals for clothing and shelter, hunted large game like bison, and fished river systems. They lived with, but also manipulated the land to provide food and shelter for themselves.

Plains natives employed fire as one of these environmental tools. Charcoal layers provide archeological evidence that Native American populations all over the Midwest and in Omaha used fire regularly (Roos, 2018). The multiple charcoal layers’ present suggest frequent, large-scale burning around the time period when the Omaha tribe were present in the area.

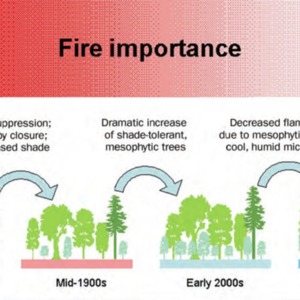

Archeologists often speculate as to the purpose of such wide-ranging fire use. Some argue that natives burned landscapes in spiritual traditions, to improve the range of sight over the landscape, or to open migration pathways (Lewis, 1993). Most agree they were used for hunting though (Delcourt and Delcourt, 1997). Tribes used controlled burning to drive the megafauna (including bison) into hunting areas. They controlled the migration of animals; thus, increasing the impact and effectiveness of hunting. This practice was especially important before the re-arrival of horses when hunting was done on foot (Hämäläinen, 2003). Fire opened diverse resources to human use such as animal meat, bones, buckskin, hair, rawhide, stomach, and horns; all of which had multiple uses including clothing, shelter, tools such as arrowheads, and many more (Natives - Native Americans). Plains burning drastically changed the composition of the land. Fire promotes plant species that are fire-tolerant, which tend to be fast-spreading, short-lived plants such as the prairie grasses that dominated much of the Midwest. Fire also suppressed large tree species that now are more prevalent (Figure II).

In addition to promoting fire tolerant species, anthropogenic fire regimes cleared brush, promoted seed germination, and increased resources yields (Klimaszewski-Patterson and Mensin, 2016). All of these had a large impact on the environment of the prairies in and around Nebraska for centuries. In short, this increase in fire improved soil fertility, which favored native species. This increased biodiversification of plants, including grasses, forbs, and trees. Biodiverse vegetation promoted faunal biodiversity as well. Beyond hunting, fire use was beneficial for soil fertility, which improved Native agriculture.

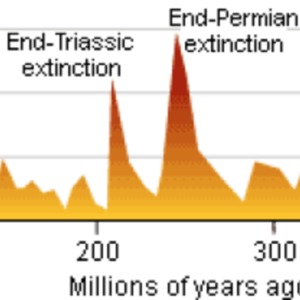

Arrowheads used for hunting had global impacts such as the overkilling of animals like American bison. This extinction not only included bison, but also the extinction of species such as birds, lemmings, and salamanders. It is unknown how many mammalian species disappeared, but it is estimated that at least thirty-five mammalian genera had vanished. Most mammals that weighed more than one hundred pounds became extinct because of how they would have been seen as attractive to hunters. Tusked mammoths and mastodons, ground sloths, rhinoceros-sized pampatheres, and giant armadillos also vanished. Other herbivores also vanished (Krech, 2018).

The overkill hypothesis states that extinction is a result because of human hunting which in turn causes death rates to exceed birth rates. This implies that humans have a direct impact on overhunting and the extinction of animals. Koch and Barnosky (2006) similarly found that about fifty thousand years ago, ecosystems all over the world were populated with large animals, but they are now extinct. They stated that worldwide, 90 genera of mammals that weighed over 44 kg had disappeared. Specifically, in North America, there used to proboscideans, giant sloths, camels, saber-tooth cats, beavers, etc. By about 10,000 years ago, most of these animals had vanished. The extinction of these large animals provides strong support that humans contributed to the extinction of these animals and this shows the relation of mass extinctions to the Anthropocene. (Figure III) In addition, this extinction happened on a global scale.

The Native American hunting patterns did influence the species composition, though not as much as other mass extinctions. Plains peoples have shaped the environment for centuries, but it is important to consider the dynamic world that the hunters were operating in during that time. For example, Isenberg (2000) looks at how the destruction of bison as the result of a complex process that involves the natural environment of Great Plains, the invasion of the Euro Americans, as well as the economy of the Plains Indians. There were natural causes of death such as fires, drowning, and competition from other grazers that all affected the population of bison on the plains. Natural mortality also could have aided in the catastrophic decline in the population of bison. The combination of the hunting practices in the Great Plains as well as the volatility of the natural environment both aided in the destruction of these herds of animals which is important to keep in mind.

North American Native Americans were not the only peoples who used fire or projectiles to change and manipulate the landscape around them. In fact, use of fire as a tool for hunting likely predates the evolution of the species (Guthrie, 1970). Human communities on every inhabited continent wielded fire and many developed projectile hunting tools (James, et. al. 1989). All over the world there was environmental changes cause by fire because the fire was being controlled by humans. Indicating global environmental, anthropogenic changes. These changes, while not representing a traditional “golden spike” should be considered when talking about the anthropocene for several reasons. Some include that it was not localized to one area, there were large scale environmental effects, and the changes were caused by human influence. The ecological changes represented in the transition to increased fire regimes is something that has continued to be studied today.

The “Anthropocene” designation claims that the earth has entered the “Age of Humans”. It is important, therefore, to consider the full measure of humanity’s long history of environmental impact. These arrowheads represent the impact of fire and hunting on the global environment. Current conservation efforts in the United States and Canada have been increasingly focused on restoring the landscape to its “pristine condition, which is often defined by the absence of people (Wooster, 1996). This has the unfortunate consequence of erasing the long history of people from the landscape. If the arrowheads teach us anything, it’s that people have played an integral part in creating these “pristine” areas. The modernist bias of the Anthropocene debate threatens that as well. Where the focus is on increasing fire regimes and megafaunal grazers such as bison. While increasing megafauna like bison would be considered more like when there were no humans, increasing fire use would actually be characteristic of when Native Americans were present, not when there were no humans in North America (Matlack, 2013). Despite these minor inconsistencies, it is evident that the impact of the Native American tools used for hunting, arrowheads and fire, have caused a global impact, which is why they should be considered when discussing the Anthropocene.

Creator

Kimberly Jurado

Source

Bohr, Roland. 2016. “Bows & Arrows.” Canada’s History 96 (5): 22–29

Carrington, Damian. 2016. “The Anthropocene epoch: scientists declare dawn of human-influenced age” The Guardian. Accessed December 8, 2018 https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/aug/29/declare-anthropocene-epoch-experts-urge-geological-congress-human-impact-earth

Delcourt, Hazel R., and Paul A. Delcourt. "Pre-Columbian Native American Use of Fire on Southern Appalachian Landscapes." Conservation Biology 11, no. 4 (1997): 1010-014. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2387336.

“Extinctions: Georges Cuvier.” Digital image. Understanding Evolution. Accessed November 6, 2018. https://evolution.berkeley.edu/evolibrary/article/history_08

Fagan, Brian. "Bison Hunters of the Northern Plains." Archaeology 47, no. 3 (1994): 37-41. Accessed October 7, 2018 http://www.jstor.org/stable/41766565.

Fletcher, C. Alice. Life among the Indians: First Fieldwork among the Sioux and Omahas ed. Scherer, C. Joanna, DeMallie, J. Raymond (University of Nebraska Press, 2013).

Guthrie, R. D. "Bison Evolution and Zoogeography in North America During the Pleistocene." The Quarterly Review of Biology45, no. 1 (1970): 1-15. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2817929

Isenberg, Andrew C., The Destruction of Bison. New Jersey: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Jin, Y.G, Wang, Y, Wang, W, Shang, Q.H, Cao, C.Q, Erwin, D.H. “Pattern of Marine Mass Extinction Near the Permian-Triassic Boundary in South China” Science 21 (2000). Accessed November 6, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.289.5478.432

Klimaszewski-Patterson, Anna, Mensing, A. Scott. “Multi-disciplinary approach to identifying Native American impacts on Late Holocene forest dynamics in the southern sierra Nevada range California, USA.” Anthropocene 15 (2016): 37-48. Accessed October 8, 2018. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2213305416300327

Koch, P.L., Barnowsky, A.D. “Late Quaternary Extinctions: State of the Debate” The Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 37 (2006): 215-250. Accessed December 8, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132415

Krech, Shepard. “Chapter One” The Ecological Indian: Myth and History (W.W. Norton and Company, 1999). https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/first/k/krech-indian.html

Laliberte, Andrea S., and William J. Ripple. “Wildlife Encounters by Lewis and Clark: A Spatial Analysis of Interactions between Native Americans and Wildlife.” BioScience53, no. 10 (October 2003): 994–1003.

Lewis, David Rich. "Native Americans and the Environment: A Survey of Twentieth-Century Issues." American Indian Quarterly 19, no. 3 (1995): 423-50. doi:10.2307/1185599.

Lewis, David Rich. "Still Native: The Significance of Native Americans in the History of the Twentieth-Century American West." The Western Historical Quarterly 24, no. 2 (1993): 203-27. doi:10.2307/970936.

Loendorf, Chris, Lynn Simon, Daniel Dybowski, M. Kyle Woodson, R. Scott Plumlee, Shari Tiedens, and Michael Withrow. 2015. “Warfare and Big Game Hunting: Flaked-Stone Projectile Points along the Middle Gila River in Arizona.” Antiquity 89 (346): 940–53. doi:10.15184/aqy.2015.28.

“Natives - Native Americans” All about Bison. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://allaboutbison.com/natives/

Nowacki, Gregory J, Abrams, Marc. D. “The Demise of Fire and “Mesophcation” of Forests in the Eastern United States” Image. BioScience 58 no. 2 (February 2008).

Matlack, R. Glenn. “Reassessment of the Use of Fires as a Management Tool in Deciduous Forests of Eastern North America” Conservation Biology 27 no. 5 (September 2013). Accessed October 7, 2018. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/cobi.12121

Pekka, Hämäläinen; The Rise and Fall of Plains Indian Horse Cultures, Journal of American History, Volume 90, Issue 3, 1 December 2003, Pages 833–862, https://doi.org/10.2307/3660878

Roos, I. Christopher, Zedeno, N. Maria, Hollenback, L. Kacy, Erlick, M.H. Mary. “Indigenous impacts on North American Great Plains fire regimes of the past millennium.” National Academy of Sciences. August, 2018. Accessed October 7, 2018. http://www.pnas.org/content/115/32/8143/tab-article-info

“Samantha Projectile Point, Samantha Arrowhead” Projectile Points Database. Accessed October 7, 2018. http://www.projectilepoints.net/Points/Samantha_Dart.html

Steven R. James, R. W. Dennell, Allan S. Gilbert, Henry T. Lewis, J. A. J. Gowlett, Thomas F. Lynch, W. C. McGrew, Charles R. Peters, Geoffrey G. Pope, Ann B. Stahl, and Steven R. James, "Hominid Use of Fire in the Lower and Middle Pleistocene: A Review of the Evidence [and Comments and Replies]," Current Anthropology 30, no. 1 (Feb., 1989): 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1086/203705

“The Omaha Indians - True Nebraskans” Legends of America: Exploring history, destinations, people, & legends of this great country since 2003. Accessed December 8, 2018. https://www.legendsofamerica.com/na-omaha/

Wakeley, C. Arthur. Omaha: The Gate City and Douglas County Nebraska (The S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1917)

Wooster, M. Martin. 1996. “The Digest: Science and environment.” American Enterprise. 7, no. 4: 90. Accessed October 8, 2018.

Rights

Collection

Citation

Embed

Copy the code below into your web page