Housing Advertisement

Title

Subject

Description

At 6520 Bedford Avenue, a two-story home stands equipped with seven bedrooms, fresh oak and maple floors, a brand new kitchen, and a garage that can accomodate a car comfortably. In the early 1990s, this house was sure to sell on sight, as described in the advertisement looking for new tenants. (Figure I) This paper analyzes that very Bee-News ad for the house at 6520 Bedford Avenue. The ad symbolizes the multiple annexations that took place in the Omaha area in the early nineteenth century, the city’s first period of suburbanization. Like most cities in the United States, Omaha grew tremendously during the period of 1880 to 1920, both in regard to population and area. From 1880 to 1920, Omaha’s population grew from 30,000 people to 200,000 people (Chudacoff 1972, 9). This first period of suburbanization laid the foundation for the more famous boom in suburbanization that took place after World War II. By serving as a reminder of suburbanization and its negative environmental effects, the housing ad connects Omaha to global environmental change in the age of the Anthropocene.

The housing ad likely appeared in the 1920s. The house itself was built in 1912, but the ad reads that the house is “as good as new,” so it is likely the ad took place a few years later. The real estate company that put this house on the market was The Byron Reed Company. The history of The Byron Reed Company dates back to 1856 when the company was first founded, but Byron Reed had a significant presence in Omaha’s political councils long before establishing his company (Durham). The total price of the home is set at $4,650 with $40 monthly payments. These prices mirror the housing prices of the 1920s. Additionally, the house is referred to as a “Benson bargain.” Given that Benson was annexed into Omaha in 1917 in addition with all of the other factors, it is reasonable to assume the housing ad took place in the 1920s.

Omaha’s public transportation system at the turn of the twentieth century drove Omaha’s increased land usage. (Chudacoff 1972, 9). It included horse railways and railway lines. The housing ad even mentions that the home is located near the Benson carline. The number of houses and total value of buildings in Omaha reflect this change in land consumption. By just 1884, there were 1174 new homes in Omaha (Chudacoff 1972, 14). In 1810, the total value of buildings was one million dollars. By 1890, the total reached 8 million (Chudacoff 1972, 14). Omaha experienced a construction boom from 1900 to 1920. Specifically, there were many lots available in Benson and Dundee, most of these being “ready-built” houses built by a single building firm with a standardized plan (Chudacoff 1972, 121).

Initially, Benson was connected to the city by trolley lines (Chudacoff 1972, 18). In 1917, what was once “Benson Place” was annexed into the city of Omaha. This occurred simultaneously with annexation of Florence and two years after the annexation of South Omaha and Dundee. Benson and Florence were the first two suburbs that surrounded Omaha to be annexed under the state law, passed in 1917, that permitted annexation without a popular vote (Omaha World Herald 1977). The annexation movement during these years was driven by both business leaders and public administrators in an effort to grow Omaha and its tax revenue (Persigehl 2017). These annexations sometimes faced public opposition. For example, many people opposed annexing the city of South Omaha. In an article written in the Omaha World Herald titled South Omaha Business Men Fight Annexation, the author interviewed the president of the South Omaha Commercial club. In this interview, he expressed deep concern for the future of the city’s education system, real estate value, and economic debt (Omaha World Herald, 1906).

Neighborhoods such as Benson and the growth of Omaha demonstrate the first stages of suburbanization. Today, the house advertised in the ad is be considered much closer to the center of Omaha than the metropolis’ western suburbs. Omaha now sits at 127.09 square miles with more suburban areas on the outskirts (United States Census Bureau). Omaha, like many industrial cities experienced suburbanization in the late 1800s and early 1900s and its first major suburban expansion took place in the 1920s. In 1922, 1,500 new houses were created in western neighborhoods (Larsen 2007, 197-198). The rich started to move to the suburbs around this same time. Larsen writes, “Builders, emphasizing the advantages of the automobile and the prospects of a cycle of rising land prices, lured rich Omahans away from the older north-side enclaves of Kountze Place and Miller Park to Fairacres and other western areas” (Larsen 2007, 197). As the Larsen quote hints at, the first few decades of the 1900s also saw an increase in the number of cars. In 1913 Nebraska had 25,617 registered vehicles and by 1920 there were 100,534 (Larsen 2007, 193). The increased popularity of the automobile caused a drastic reduction in the use of Omaha’s public transportation in the 1920s.

Omaha’s first period of annexation and slight suburbanization is comparable to other cities across the United States as well. The increased popularity of the automobile across the country meant that people did not need to stay near streetcar lines. Because of this, urban development began to spread outward (Williams 2000, 5). Donald C. Williams writes in Urban Sprawl: A Reference Handbook, “Some of these early suburbs were absorbed by the older cities as each grew ineluctably toward the other over the ensuing decades” (Williams 2000, 5). Just like in Omaha, Williams argues that many of these suburbs were resistant to urban annexation (Williams 2000, 5). Additionally, the increase in houses being built in Omaha parallels the national scene. Under the Hoover administration, developers built twice as many homes in 1925 (937,000) than in 1922 (Rome 2001, 23). Though major suburbanization took place in the post World War II era, this large jump would not have taken place if it was not for the initial suburbanization in the early 1900s.

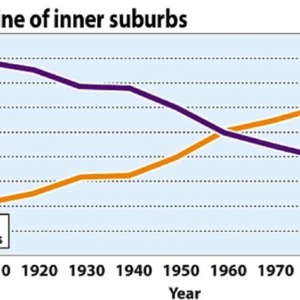

The boom in suburbanization after World War II was much bigger than the first. Before WWII a mere 13% of Americans lived in the suburbs but, just over seven decades later, that number would rise to half of the U.S. population (Nicolaides and Wiese 2017, 1). The Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History states that there were “two key chronological stages in suburban history since 1945: the expansive, racialized, mass suburbanization of the postwar years (1945–1970) and an era of intensive social diversification and metropolitan complexity (since 1970)” (Nicolaides and Wiese 2017, 1). During the first era of post-WWII suburbanization, the rise in populations that invaded the suburban neighborhoods caused a dramatic boost in real estate production. (Figure II) This likely resulted in an increase in housing ads similar to the one examined in this paper and certainly accelerated the environmental impacts of development.

Though suburbanization was especially prevalent in the United States, the trend of suburbanization is not isolated to the United States. It was felt by many cities in different countries across the world. Cities in Europe, New Zealand, Japan, and Australia have all witnessed a decline in city populations due to increased popularity of the suburbs (Mason and Nigmatullina 2011, 317). For example, in West Germany, the average living area per person grew from from 22 square meters to 42 square meters from 1965 to 2010 because of suburbanization (Rontos et al. 2006). However, in places like Western Europe, the social and spatial segregation that is present in suburbanization in the United States, is less prevalent (Leetma and Tammaru 2007, 129). Though not every country has experienced suburbanization to the same extent as the United States has, the effects of it are still felt globally.

Suburbanization is a major contributor to earth systems change in the Anthropocene. Various agricultural systems experienced change during suburbanization periods due to the overuse of rural and agricultural lands for the purpose of commercial real-estate (Wood 1988). A specific example of this can be seen through the conversion of farm lands in the state of New Jersey to urban establishments during the postwar period (Lopez et al. 1988). Once rich, fertile lands used to harvest economically and environmentally essential crops increasingly transformed into lightly populated suburbs. In hindsight, the transition from rural land to populated neighborhoods could have been beneficial for the regions surrounding high-density cities. It has been theorized that living in cities where there are smaller homes and public transportation is heavily utilized can be very beneficial for the environment (Owen 2009, 2-4). However, because of the supplemental costs, like those involving increased gasoline consumption and household energy footprints, the benefits of suburbanization did not outweigh the consequences.

Construction efforts reached new levels in the years following the war and in order to meet the increased housing demand many trees and nearby forestry had to be utilized (Wells 2012, 255). This depleted vital natural resources such as vegetation that provided an oxygen supply and destroyed ecosystems that were important in many biological processes such as the nitrogen and phosphorus cycles (Grimm et al 2008). During the second era of suburbanization after 1970, the amount of land used for real-estate development skyrocketed. Around 43 million acres of rural land was being consumed and an estimate stated that “the United States was losing two acres of farmland per minute to suburban development” (Nicolaides and Wiese 2017, 19). Land resources were quickly exhausted in many suburban communities to make way for houses similar to the “Benson Bargain.”

The move to suburbia expanded commuting distances for those who still retained jobs in the urban city but relocated their families to the suburbs. Commuting back and forth from homes, such as the one in the housing ad, used to involve public transportation. However, once reliance on personal automobiles increased, there was a shift away from public transportation in the suburbs. Norman G. Palhous and Jerry D. Ward argue that this is because with the further development of the suburbs, less travel is aimed at the city center (United States Department of Transportation 74, 25). Global car use rose significantly as suburbanization expanded through some of the nation’s most populated urban cities. As put by David J. Cieslewicz, “To a large extent, to determine the environmental impact of sprawl we need to simply follow the cars” (Cieslewicz 2002, 24).

In an article titled The Environmental Impact of Suburbanization by Matthew Kahn, he states that “suburbanites drove 31 percent more than central city residents in 1995” (Kahn 2000, 4) and contributed to the higher emissions that were reported in his study. The release of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere has detrimental effects on many of Earth’s ecosystems. As private car use transitioned from a luxury to a necessity in the U.S., the atmosphere and the environment began to deteriorate. Cieslewicz argues that the increased use of cars cannot be attributed simply to population growth, since the number of automobile miles traveled increased 140 percent from 1950 to 1990 while the United States population only grew 40% (Cieslewicz 2002, 24).

Suburbanization and all its effects are still present today. By now, many are aware of the environmental impacts of urban sprawl, however the benefits of suburbia keep the suburbs populated and ever growing. To this day, it still rings true that the suburbs furthest from the city cause the most environmental damage. In 2013, Christopher Jones and Daniel M. Kammen conducted a study on this very issue. They found that US households contribute 20 percent of annual global greenhouse gas emissions (Jones and Kammen 2013, 895). The Environmental Protection Agency states that 11 percent of greenhouse gas emission has commercial and residential causes and that 28% comes from transportation (EPA). The increased size of houses also plays a key role in elevated energy consumption in the suburbs. The housing ad boasts that the second floor has three large bedrooms. More spacious bedrooms means more space to heat and cool, requiring more energy. (Figure III)

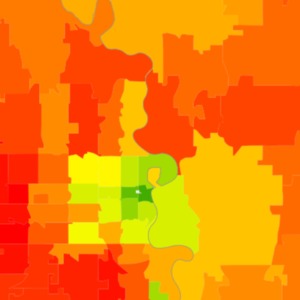

Using Atlanta as an example, Jones and Kammen (2013) argue that even when factors such as pricing and weather are the same, “The zip codes with the highest energy-related emissions are concentrated in a tight band of suburbs between 15 and 45 miles from the city center” (Jones and Kammen 2013, 898). To provide an example from Omaha, central Omaha has an average of household carbon footprint of 27.40, compared to 57.45 in West Omaha (Jones and Kammen 2013). The difference is even more noticeable in regard to transportation related emissions, ranging from <10 tCO2e per household in the center of the city to >25 tCO2e in the suburbs farthest from the city (Jones and Kammen 2013, 898). As for Omaha, residents of Central Omaha drive an average of 9,392 miles per year while residents of West Omaha drive an average of 24,057 (Jones and Kammen 2013).

Depicting suburbanization in Omaha, the housing ad also represents the the connection Omaha has to global history and the Anthropocene. Suburbs demanded increased energy and land consumption, releasing more greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere than city cores. Our best bet at combating the negative environmental effects of suburbanization might be a return to city life. Jones and Kammen argue that in large metropolitan areas with dense populations, even if the city center has low household carbon footprints, the surrounding suburbs with large household carbon footprints “more than [offset] the benefit of low carbon areas in city centers” (Jones and Kammen, 899). It is thus clear that the conversion of rural lands, increased car use, and increased energy consumption are all result in negative environmental change caused by suburbanization in the age of the Anthropocene.

Creator

Emery Staton

Source

Chudacoff, Howard P. 1972. Mobile Americans: Residential and Social Mobility in Omaha 1880-1920. New York: Oxford University Press.

Cieslewicz, David. J. 2000. “The Environmental Impacts of Sprawl.” In Urban Sprawl: Causes, Consequences, and Policy Responses, edited by Gregory D. Squires, 23-38. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute Press.

The Land Grab 1855. Permanent Exhibit, Durham Museum.

Environmental Protection Agency. “Greenhouse Gas Emissions.” Environmental Protection Agency. Accessed November 6, 2018. https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/sources-greenhouse-gas-emissions.

Grimm, Nancy B., David Foster, Peter Groffman, J. Morgan Grove, Charles S. Hopkinson, Knute J. Nadelhoffer, Diane E. Pataki, and Debra PC Peters. 2008. "The Changing Landscape: Ecosystem Responses to Urbanization and Pollution Across Climatic and Societal Gradients." Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 6, no. 5 (June): 264-272. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20440887

Jones, Christopher and Daniel Kammen. 2014. “Spatial Distribution of U.S. Household Carbon Footprints Reveals Suburbanization Undermines Greenhouse Gas Benefits of Urban Population Density.” Environmental Science and Technology 48, no. 2 (December): 895–902. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/es4034364.

Kahn, Matthew E. 2000.“The Environmental Impact of Suburbanization.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 19, no. 4 (Autumn 2000): 569-586. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3325575.

Lawrence Harold. 2007. Upstream Metropolis: An Urban Biography of Omaha and Council Bluffs. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

“Leave Omaha Suburbs Alone”.Omaha World Herald. (Omaha, NE) January 2, 1902.

Leetma, Kadri and Tiit Tammaru. 2007. “Suburbanization in Countries in Transition: Destinations of Suburbanizers in the Tallinn Metropolitan Area.” Geografiska Annaler. Series B, Human Geography 89, no. 2: 127-146.

“Little Strip of Land May Keep Benson Out”. Omaha World Herald. (Omaha, NE). March 14, 1915.

Lopez, Rigoberto A., Adesoji O. Adelaja, and Margaret S. Andrews. 1988. “The Effects of Suburbanization onAgriculture.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 70 (2), 346-358. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1242075

Mason, Robert J. and Lylia Nigmatuillna. 2011. “Suburbanization and Sustainability in Metrpopolitan Moscow.” Geographical Review 101, no. 3 (July): 316-333. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4130363

Nicolaides, Becky, and Wiese, Andrew 2017. "Suburbanization in the United States after 1945." Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History. 7 Nov. 2018. http://americanhistory.oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.001.0001/acrefore-9780199329175-e-64.

Owen, David. 2009. Green Metropolis: Why Living Smaller, Living Closer, and Driving Less are the Keys to Sustainability, New York: Riverhead Books.

Persigehl, Linda. 2017. “Battle for Benson: The 100th Anniversary of its Annexation.” Omaha Magazine, October 18. Accessed November 5, 2018. http://omahamagazine.com/articles/battle-for-benson/.

Rome, Adam. 2001. The Bulldozer in the Countryside: Suburban Sprawl and the Rise of American Environmentalism. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Rontos, Kostas & Mavroudis, Christos & Georgiadis, Theodore. 2006. “Suburbanization: A Post World War II Phenomenon in the Athens Metropolitan Area, Greece.” https://www.researchgate.net/publication/23732333_Suburbanization_A_Post_World_W ar_II_Phenomenon_in_the_Athens_Metropolitan_Area_Greece

“South Omaha Business Men Fight Annexation”. Omaha World Herald. (Omaha, NE). November 28, 1906.

United States Census Bureau. “Quick Facts: Omaha city, Nebraska.” United States Census Bureau. Accessed November 2, 2018. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/omahacitynebraska.

United States Department of Transportation. 1974. Suburbanization and its Implications for Urban Transportation Systems, by Jerry D. Ward and Norman G. Paulhus, Jr. Washington DC. Wells, Christopher W. 2012. Car Country: An Environmental History. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Whitney, Kristoffer. 2010. “Living Lawns, Dying Waters: The Suburban Boom, Nitrogenou Fertilizers, and the Nonpoint Source Pollution Dilemma.” Technology and Culture 51, no. 3 (July): 652-674. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40927990.

Williams, Donald C. 2000. Urban Sprawl: A Reference Handbook. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, Inc., 2000.

Wood, Joseph S. 1988. "Suburbanization of Center City." Geographical Review 78, no. 3: 325-29.

Rights

Collection

Citation

Embed

Copy the code below into your web page