Omaha Streetmap and Guide

Title

Omaha Streetmap and Guide

Subject

In a world before smartphones, Omaha residents relied on paper maps to navigate the city. The Omaha Street Map and Guide was one such map. It also included locations of local attractions and businesses. As a historical document, it captures a moment in Omaha’s past when owning a private car became popular in America. It is a snapshot in time, before highways supercharged westward suburbanization. What it does not show is also important. Rich people, the majority of whom were white, bought cars and moved to the suburbs. Lower class minorities continued to live closer to the city. This Street Map and Guide highlights the challenge of using objects to tell Anthropocene stories. It shows change in the physical layout of Omaha, but only hints to its deeper racial implications. Omaha is not unique for suburbanizing because cities around the globe shifted too. This map and guide reminds us how suburbanization relates to the Anthropocene.

Description

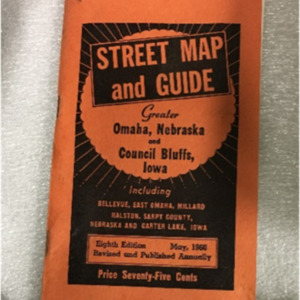

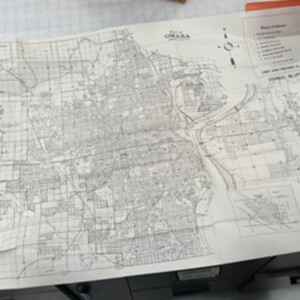

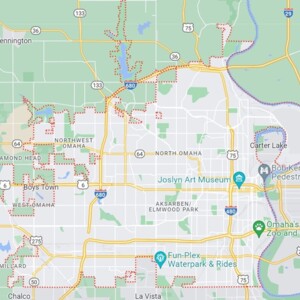

Imagine a world without smartphones… How would anyone get around a busy city like Omaha? In 1960, Omaha residents would have used this Street Map and Guide of the Greater Omaha, Nebraska and Council Bluffs, Iowa area (Appendix, Figure 1) like a modern-day equivalent to google maps combined with a city directory. The map from 1960 is a snapshot in time of Omaha’s growing city limits. Comparing it to a map of Omaha today (Appendix, Figure 2), it is clear that the city has greatly expanded away from downtown since 1960, referencing the rush to suburbanization. The Omaha Street Map and Guide symbolizes the hidden history of suburbanization and how it impacted the physical and racial layout of Omaha in a way similar to cities around the world, as related to the shifting transportation industry and the Anthropocene.

The 1960 Street Map and Guide of Greater Omaha, Nebraska, and Council Bluffs, Iowa includes a map of the surrounding areas and a guide to some local hot spots. The Street Guide Publishing Company (SGPC) updated and published the map annually in Omaha. The map was mass-produced and available at bookstores, newsstands, drug stores, and other public places for 75 cents, which is equivalent to around $7.11 in today’s currency (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2022). According to the U.S. Department of Labor-Wage and Hour Division, this was considered to be expensive, as the minimum wage during the 1960s was around $1.00. The guide includes a street map, but also important facts regarding Omaha, such as population size and city accomplishments, along with advertisements for businesses and events in Omaha. The map also includes sites of economic and cultural interest, such as banks and schools, and provides the establishments’ addresses and phone numbers. The functionality of the map and guide was critical, so the SGPC took care to update the map annually. By 1960, it was already in its 8th edition. The list of businesses in this small booklet is surprisingly extensive – including over 500 entries (Figure 1).

This history of Omaha’s urban and suburban growth correlates with the history of advances in transportation within the city. The founding of the city of Omaha occurred in 1854 around the development of the Union Pacific Railroad, one of the first mechanisms of public transportation in the United States. This increased the number of people and commercial goods coming in and out of the new city, causing Omaha to flourish (Thavenet, 1960). During much of its early history, however, Omaha's city limits remained within less than 5 miles of the Missouri River and only consisted of a few buildings (Hendee, 2015). Even in the early 1960s, its western city limits scarcely moved beyond 118th street, as seen in Figure 1.

Saving time and energy for travel is what prompted changes in the transportation industry throughout Omaha’s history. In 1867, the Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Nebraska organized an act that would create the Omaha Horse Railway Company (Bloomfield, 2005). This promptly led to the construction of a railway, resulting in the growth of the city. Initially, the lines followed downtown and reached no farther than 16th street. Eventually, they expanded to reach the North and South sides of Omaha (Thomas, 2019). Omaha’s physical layout changed as an increasing number of horse-drawn streetcar lines were laid at both ends of the city. As the lines expanded, so did the placement of houses. Omaha residents were now able to live farther away from where they worked, as the horse-drawn streetcar cut their commuting times. As a result, the city created new housing communities, referred to as “streetcar suburbs”. Omaha established “streetcar suburbs” in the neighborhoods of Dundee and Kountze Place in 1880, Benson in 1887, Miller Park in 1891, and Minne Lusa in 1916 (Fletcher, 2016). This early westward expansion in Omaha would serve as a template for later suburban growth.

As people began to live further out from the city, they pushed for an even more reliable and quicker public transportation method. We see a shift in the energy source of public transportation in Omaha from running on horse-drawn streetcars’ animal muscle power to using machine power that would get the electric streetcar lines into action. In 1887, the Cable Tramway Company brought the electric streetcar into Omaha’s transportation narrative (Fletcher, 2017). This posed an immediate threat to the Omaha Horse Railway Company and its lines, causing the two companies to merge and form the Omaha Street Railway Company (Fletcher, 2017). For the electrical streetcars to operate at their best potential, this company updated the lines throughout the city with more heavy-duty tracks. Due to Omaha’s innovative transportation methods, more lines were built to support the popularity of public transportation, causing an increase in land usage (Chudacoff, 1972).

With companies competing with one another over lines, the rights to tracks and streets were in constant dispute. In 1925, the city implemented buses into the streetcar system (Thavanet, 1960). Buses served to transport riders past the ends of the lines, causing further population and housing growth in the West. After drivers participated in strikes over labor wages, Omaha could no longer fund all the laborers that it took to maintain both the streetcar lines and the bus lines (Thavenet, 1960). The city realized that it could not support both modes of transportation. In 1955, the last streetcar ran and the Omaha Street Railway Company sold many of them for other uses, such as serving as dormitories for a boy’s camp (Thavanet, 1960). Popular new bus lines replaced the outdated electrical streetcar lines. But public transportation wouldn't stay popular for long.

As Omaha’s suburbs kept growing, the transportation industry experienced a shift in demand from public to private transportation. In Omaha and cities around the world, public transportation like buses and streetcars often did not reach far into the suburbs, so one of the only transportation options for suburban residents was to buy a private car (Mason & Nigmatullina, 2011). This was a cyclical process because as the car industry grew, more people were able to move farther away from the city, thus expanding the suburbs. This was evident in the simultaneous boom of houses constructed on the west side of Omaha and the skyrocketing numbers of registered vehicles in the state of Nebraska in the early 20th century. According to Lawrence, Nebraska had 25,617 registered auto vehicles in 1913 and just seven years later, there were 100,534 (Lawrence, 2007). At the same time, the western neighborhoods of Omaha grew by 1,500 houses in just 1922 alone (Lawrence, 2007). Owning a private car allowed residents to travel longer over a shorter period, so many people who owned cars chose to live farther away from downtown.

When the Street Guide Publishing Company published this map and guide in 1960 around 40 years after this housing and private transportation boom, the private car industry was still growing, corresponding with an even greater decrease in the popularity of public transportation in Nebraska. As more people purchased private cars, fewer people bought public transport vehicles. From 1955 to 1965, the number of registered private auto vehicles rose from 503,362 to 633,518, while the number of registered public buses and other assorted vehicles only rose from 70,859 to 93,695 in the same time frame (Nebraska DMV). The private transportation industry was growing at a much faster rate than the public transportation industry. The decline in public transportation after World War II directly relates to the growth in the suburbs. Before WWII, only 13% of United States residents lived in the suburbs but this number grew to more than 50% by 2010 (Nicolaides & Wiese, 2017).

Omaha is not unique in its rush to suburbanization. In fact, after World War II, Australian and Canadian cities experienced similar growth rates in their suburbs as compared to the United States (Mason & Nigmatullina, 2011). Urban sprawl was common after World War II among these wealthier countries because with soldiers arriving home, the net number of nuclear families increased, resulting in a ‘baby boom’ (Nicolaides & Wiese, 2017). With more kids comes the need for more space, so houses in the suburbs with bigger yards were often the ideal option for bigger families (Nicolaides & Wiese, 2017).

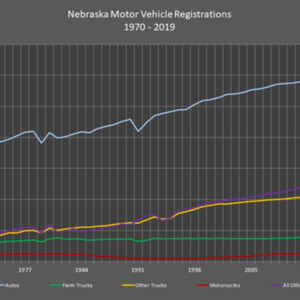

The expansion of cities into suburbs is not merely an issue of the past. According to the United States Census Bureau, the area of Omaha as of 2020 is 141.57 square miles (US Census Bureau, 2020). The city grew more than 14 square miles in the past ten years, indicating that the city and its suburbs are continuing to grow. Once again, Omaha is not the only example of modern-day suburbanization. Mason and Nigmatullina state that “Indeed, most core cities, not only in Europe and the United States but also in Australia, New Zealand and Japan, have lost population in recent decades” (Mason & Nigmatullina, 2011). The decrease in urban populations results in urban sprawl and an increase in suburbs. Continued suburbanization is also evident in the ever-growing private transportation sector. Since 1998, the number of registered auto vehicles in Nebraska has increased by more than 200,000 (Appendix, Figure 4). The growth of the private car industry allows for even greater rates of suburbanization as people can commute longer distances over shorter periods.

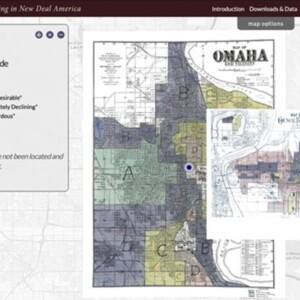

With the rapid building of houses in the suburbs across America throughout the 20th century, the issue of funding came into play. In 1933, the Roosevelt administration proposed the New Deal to help promote economic growth after by creating new federal government programs to salvage the housing market after the Great Depression caused house values to decrease and foreclosure to increase (Walker 2022). Government agencies such as the Home Owners' Loan Corporation and the Federal Home Loan Bank Board graded a neighborhood based on its quality of housing, the recent history of sale and rent values, and the racial and ethnic identity and a class of residents that lived there (Appendix, Figure 3). This is a term known as redlining, which was a discriminatory practice that withheld minorities from mortgages and taking out loans because they were not considered trustworthy to pay back what the bank loaned them. According to Turner, “Redlining is said to occur when otherwise comparable loans are more likely to be denied for houses in minority neighborhoods than for houses in white neighborhoods, even though all credit-relevant characteristics of applicants, properties, and loans are the same” (Turner, 1999). This meant that many minorities were unable to purchase houses in white neighborhoods, forcing them to purchase within the areas viewed as ‘hazardous’ (Appendix, Figure 3). Although redlining is now illegal, this explains why even today in Omaha we see a “white flight” of white people moving to the higher rated predominantly middle to upper-class areas while middle to lower-class minorities live in the lower-graded urban areas (Boustan, 2013). Other factors in the segregation of housing include, “population influx, labor competition, racial tensions, and racial violence that led to White animosity and the rise of racially restrictive covenants in housing, which limited the ability of Black citizens to live and purchase homes in many areas” (Strand, 1970).

Apart from detrimentally affecting the social and racial layout of Omaha, suburban growth also caused harm to the surrounding ecosystems. In cities around the world, to create space for new homes and businesses in the suburbs, natural environments are often left destroyed or fragmented (Grimm et al. 2008). Since cities and suburbs are common in most parts of the globe and do not seem to be slowing in popularity, many ecosystems around the world are continually affected. This period in which “human activity acts as a major driving factor, if not the dominant process, in modifying the landscape and the environment” has been described as the Anthropocene (Certini, et al. 2011). Suburbanization plays into the Anthropocene because as cities around the globe grow, the surrounding environment is continually modified and affected.

The 1960 Map and Guide of Omaha, Nebraska and Council Bluffs, Iowa is a snapshot in time of the area’s continued suburbanization that results from the growing private transportation industry. A quote from Mason and Nigmatullina nicely summarizes the economic, social, and environmental issues that stem from the urban expansion: “Metropolitan regions have tended to be highly fragmented and uneven, as multiple governments compete for tax revenue, provide duplicative, inefficient municipal services, and enact regulations designed to segregate residents by class and race. The resultant sprawl incurs high fiscal and environmental costs” (Mason & Nigmatullina, 2011).

Expanding cities and their suburbs around the world act as mechanisms for social segregation and continued environmental degradation. As suburbs continue to grow globally alongside the private transportation industry, the surrounding environments will continue to be destroyed. The idea of the Anthropocene reminds us of our effects on the environment.

The 1960 Street Map and Guide of Greater Omaha, Nebraska, and Council Bluffs, Iowa includes a map of the surrounding areas and a guide to some local hot spots. The Street Guide Publishing Company (SGPC) updated and published the map annually in Omaha. The map was mass-produced and available at bookstores, newsstands, drug stores, and other public places for 75 cents, which is equivalent to around $7.11 in today’s currency (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2022). According to the U.S. Department of Labor-Wage and Hour Division, this was considered to be expensive, as the minimum wage during the 1960s was around $1.00. The guide includes a street map, but also important facts regarding Omaha, such as population size and city accomplishments, along with advertisements for businesses and events in Omaha. The map also includes sites of economic and cultural interest, such as banks and schools, and provides the establishments’ addresses and phone numbers. The functionality of the map and guide was critical, so the SGPC took care to update the map annually. By 1960, it was already in its 8th edition. The list of businesses in this small booklet is surprisingly extensive – including over 500 entries (Figure 1).

This history of Omaha’s urban and suburban growth correlates with the history of advances in transportation within the city. The founding of the city of Omaha occurred in 1854 around the development of the Union Pacific Railroad, one of the first mechanisms of public transportation in the United States. This increased the number of people and commercial goods coming in and out of the new city, causing Omaha to flourish (Thavenet, 1960). During much of its early history, however, Omaha's city limits remained within less than 5 miles of the Missouri River and only consisted of a few buildings (Hendee, 2015). Even in the early 1960s, its western city limits scarcely moved beyond 118th street, as seen in Figure 1.

Saving time and energy for travel is what prompted changes in the transportation industry throughout Omaha’s history. In 1867, the Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Nebraska organized an act that would create the Omaha Horse Railway Company (Bloomfield, 2005). This promptly led to the construction of a railway, resulting in the growth of the city. Initially, the lines followed downtown and reached no farther than 16th street. Eventually, they expanded to reach the North and South sides of Omaha (Thomas, 2019). Omaha’s physical layout changed as an increasing number of horse-drawn streetcar lines were laid at both ends of the city. As the lines expanded, so did the placement of houses. Omaha residents were now able to live farther away from where they worked, as the horse-drawn streetcar cut their commuting times. As a result, the city created new housing communities, referred to as “streetcar suburbs”. Omaha established “streetcar suburbs” in the neighborhoods of Dundee and Kountze Place in 1880, Benson in 1887, Miller Park in 1891, and Minne Lusa in 1916 (Fletcher, 2016). This early westward expansion in Omaha would serve as a template for later suburban growth.

As people began to live further out from the city, they pushed for an even more reliable and quicker public transportation method. We see a shift in the energy source of public transportation in Omaha from running on horse-drawn streetcars’ animal muscle power to using machine power that would get the electric streetcar lines into action. In 1887, the Cable Tramway Company brought the electric streetcar into Omaha’s transportation narrative (Fletcher, 2017). This posed an immediate threat to the Omaha Horse Railway Company and its lines, causing the two companies to merge and form the Omaha Street Railway Company (Fletcher, 2017). For the electrical streetcars to operate at their best potential, this company updated the lines throughout the city with more heavy-duty tracks. Due to Omaha’s innovative transportation methods, more lines were built to support the popularity of public transportation, causing an increase in land usage (Chudacoff, 1972).

With companies competing with one another over lines, the rights to tracks and streets were in constant dispute. In 1925, the city implemented buses into the streetcar system (Thavanet, 1960). Buses served to transport riders past the ends of the lines, causing further population and housing growth in the West. After drivers participated in strikes over labor wages, Omaha could no longer fund all the laborers that it took to maintain both the streetcar lines and the bus lines (Thavenet, 1960). The city realized that it could not support both modes of transportation. In 1955, the last streetcar ran and the Omaha Street Railway Company sold many of them for other uses, such as serving as dormitories for a boy’s camp (Thavanet, 1960). Popular new bus lines replaced the outdated electrical streetcar lines. But public transportation wouldn't stay popular for long.

As Omaha’s suburbs kept growing, the transportation industry experienced a shift in demand from public to private transportation. In Omaha and cities around the world, public transportation like buses and streetcars often did not reach far into the suburbs, so one of the only transportation options for suburban residents was to buy a private car (Mason & Nigmatullina, 2011). This was a cyclical process because as the car industry grew, more people were able to move farther away from the city, thus expanding the suburbs. This was evident in the simultaneous boom of houses constructed on the west side of Omaha and the skyrocketing numbers of registered vehicles in the state of Nebraska in the early 20th century. According to Lawrence, Nebraska had 25,617 registered auto vehicles in 1913 and just seven years later, there were 100,534 (Lawrence, 2007). At the same time, the western neighborhoods of Omaha grew by 1,500 houses in just 1922 alone (Lawrence, 2007). Owning a private car allowed residents to travel longer over a shorter period, so many people who owned cars chose to live farther away from downtown.

When the Street Guide Publishing Company published this map and guide in 1960 around 40 years after this housing and private transportation boom, the private car industry was still growing, corresponding with an even greater decrease in the popularity of public transportation in Nebraska. As more people purchased private cars, fewer people bought public transport vehicles. From 1955 to 1965, the number of registered private auto vehicles rose from 503,362 to 633,518, while the number of registered public buses and other assorted vehicles only rose from 70,859 to 93,695 in the same time frame (Nebraska DMV). The private transportation industry was growing at a much faster rate than the public transportation industry. The decline in public transportation after World War II directly relates to the growth in the suburbs. Before WWII, only 13% of United States residents lived in the suburbs but this number grew to more than 50% by 2010 (Nicolaides & Wiese, 2017).

Omaha is not unique in its rush to suburbanization. In fact, after World War II, Australian and Canadian cities experienced similar growth rates in their suburbs as compared to the United States (Mason & Nigmatullina, 2011). Urban sprawl was common after World War II among these wealthier countries because with soldiers arriving home, the net number of nuclear families increased, resulting in a ‘baby boom’ (Nicolaides & Wiese, 2017). With more kids comes the need for more space, so houses in the suburbs with bigger yards were often the ideal option for bigger families (Nicolaides & Wiese, 2017).

The expansion of cities into suburbs is not merely an issue of the past. According to the United States Census Bureau, the area of Omaha as of 2020 is 141.57 square miles (US Census Bureau, 2020). The city grew more than 14 square miles in the past ten years, indicating that the city and its suburbs are continuing to grow. Once again, Omaha is not the only example of modern-day suburbanization. Mason and Nigmatullina state that “Indeed, most core cities, not only in Europe and the United States but also in Australia, New Zealand and Japan, have lost population in recent decades” (Mason & Nigmatullina, 2011). The decrease in urban populations results in urban sprawl and an increase in suburbs. Continued suburbanization is also evident in the ever-growing private transportation sector. Since 1998, the number of registered auto vehicles in Nebraska has increased by more than 200,000 (Appendix, Figure 4). The growth of the private car industry allows for even greater rates of suburbanization as people can commute longer distances over shorter periods.

With the rapid building of houses in the suburbs across America throughout the 20th century, the issue of funding came into play. In 1933, the Roosevelt administration proposed the New Deal to help promote economic growth after by creating new federal government programs to salvage the housing market after the Great Depression caused house values to decrease and foreclosure to increase (Walker 2022). Government agencies such as the Home Owners' Loan Corporation and the Federal Home Loan Bank Board graded a neighborhood based on its quality of housing, the recent history of sale and rent values, and the racial and ethnic identity and a class of residents that lived there (Appendix, Figure 3). This is a term known as redlining, which was a discriminatory practice that withheld minorities from mortgages and taking out loans because they were not considered trustworthy to pay back what the bank loaned them. According to Turner, “Redlining is said to occur when otherwise comparable loans are more likely to be denied for houses in minority neighborhoods than for houses in white neighborhoods, even though all credit-relevant characteristics of applicants, properties, and loans are the same” (Turner, 1999). This meant that many minorities were unable to purchase houses in white neighborhoods, forcing them to purchase within the areas viewed as ‘hazardous’ (Appendix, Figure 3). Although redlining is now illegal, this explains why even today in Omaha we see a “white flight” of white people moving to the higher rated predominantly middle to upper-class areas while middle to lower-class minorities live in the lower-graded urban areas (Boustan, 2013). Other factors in the segregation of housing include, “population influx, labor competition, racial tensions, and racial violence that led to White animosity and the rise of racially restrictive covenants in housing, which limited the ability of Black citizens to live and purchase homes in many areas” (Strand, 1970).

Apart from detrimentally affecting the social and racial layout of Omaha, suburban growth also caused harm to the surrounding ecosystems. In cities around the world, to create space for new homes and businesses in the suburbs, natural environments are often left destroyed or fragmented (Grimm et al. 2008). Since cities and suburbs are common in most parts of the globe and do not seem to be slowing in popularity, many ecosystems around the world are continually affected. This period in which “human activity acts as a major driving factor, if not the dominant process, in modifying the landscape and the environment” has been described as the Anthropocene (Certini, et al. 2011). Suburbanization plays into the Anthropocene because as cities around the globe grow, the surrounding environment is continually modified and affected.

The 1960 Map and Guide of Omaha, Nebraska and Council Bluffs, Iowa is a snapshot in time of the area’s continued suburbanization that results from the growing private transportation industry. A quote from Mason and Nigmatullina nicely summarizes the economic, social, and environmental issues that stem from the urban expansion: “Metropolitan regions have tended to be highly fragmented and uneven, as multiple governments compete for tax revenue, provide duplicative, inefficient municipal services, and enact regulations designed to segregate residents by class and race. The resultant sprawl incurs high fiscal and environmental costs” (Mason & Nigmatullina, 2011).

Expanding cities and their suburbs around the world act as mechanisms for social segregation and continued environmental degradation. As suburbs continue to grow globally alongside the private transportation industry, the surrounding environments will continue to be destroyed. The idea of the Anthropocene reminds us of our effects on the environment.

Creator

Clara Coughlan-Smith

Sabrina Morales

Sabrina Morales

Source

Boustan, Leah P., and Robert A. Margo. (2013). A Silver Lining to White Flight? White Suburbanization and African–American Homeownership, 1940–1980. Journal of Urban Economics 78: 71–80. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2013.08.001.

Chudacoff, Howard P. (1972). Mobile Americans: Residential and Social Mobility in Omaha ; 1880-1920. New York: Oxford Univ. Press.

Certini, Giamoco, and Scalenghe, Riccardo. (2011). Anthropogenic soils are the golden spikes for the Anthropocene. Sage Publications.

David Hendee / World-Herald staff writer. (2019). 1865 In Omaha: A Momentous Year. Omaha World-Herald. Accessed October 16, 2022. https://omaha.com/special_sections/in-omaha-a-momentous-year/article_72e950df-ec1f-53ae-b383-8ef47b8241fc.html.

Doug Thomas / World-Herald staff writer. (2019). Omaha's Once-Sprawling Streetcar System Now Lives Only in Memory. Omaha World-Herald. Accessed October 16, 2022. https://www.omaha.com/living/omaha-s-once-sprawling-streetcar-system-now-lives-only-in/article_faf152c0-da05-11e7-b045-2f378c682fd5.html.

Fletcher, Adam F.C., and Sam Swanson. (2022). A History of Streetcars in Benson. North Omaha History. Accessed October 21, 2022. https://northomahahistory.com/2017/03/04/benson-motor-company/.

Fletcher, Adam F.C., Wade, Linda, Lee, Steven, Mendicino, Lori, Heeren, Ann Heeren. (2022). A History of the Minne Lusa Historic District in North Omaha. North Omaha History. Accessed October 16, 2022. https://northomahahistory.com/2016/06/24/a-history-of-the-minne-lusa-historic-district-in-north-omaha-nebraska/.

Grimm, Nancy B., David Foster, Peter Groffman, J. Morgan Grove, Charles S. Hopkinson, Knute J. Nadelhoffer, Diane E. Pataki, and Debra PC Peters. (2008). The Changing Landscape: Ecosystem Responses to Urbanization and Pollution Across Climatic and Societal Gradients. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 6, no. 5 (June): 264-272. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20440887

“History of Federal Minimum Wage Rates under the Fair Labor Standards Act, 1938 - 2009.” 2022. United States Department of Labor. Accessed December 9. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/minimum-wage/history/chart.

Knute J. Nadelhoffer, Diane E. Pataki, and Debra PC Peters. (2008). The Changing Landscape: Ecosystem Responses to Urbanization and Pollution Across Climatic and Societal Gradients. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 6, no. 5 (June): 264-272. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20440887

Google. (2022). Omaha, Nebraska. Google maps. Retrieved December 8, 2022, from https://maps.google.com/

Lawrence, Harold. (2007). Upstream Metropolis: An Urban Biography of Omaha and Council Bluffs. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Mapping Inequality. Digital Scholarship Lab. (n.d.). Retrieved November 3, 2022, from https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/#loc=12/41.271/-95.991&city=omaha-ne

Mason, R.J., & Nigmatullina, L. (2011). Suburbanization and Sustainability in Metropolitan Moscow. Geographical Review, 101(3), 316–333. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41303637

Nebraska Department of Energy and Environment. (2020). Nebraska Energy Statistics: Nebraska Motor Vehicle Registrations. Nebraska Energy Office, Lincoln, NE. Accessed December 8, 2022. https://neo.ne.gov/programs/stats/inf/72a.html

Nebraska Department of Motor Vehicles, Lincoln, NE. (n.d.). DMV Annual Report. Nebraska Energy Office, Lincoln, NE.

Nicolaides, Becky, and Wiese, Andrew. (2017). Suburbanization in the United States after 1945. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History.

Peattie Elia Wilkinson and Susanne George-Bloomfield. (2005). Impertinences : Selected Writings of Elia Peattie a Journalist in the Gilded Age. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Strand, Palma J. (1970). Mirror, Mirror on the Wall...": Reflections on Fairness and Housing in the Omaha Council-Bluffs Region. CDR Home. https://dspace2.creighton.edu/xmlui/handle/10504/110116.

Thavenet, Dennis. (1960). A History of Omaha Public Transportation. DigitalCommons@UNO. Accessed December 9, 2022. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/1467/.

Turner, Margery Austin, and Felicity Skidmore. (1999). Mortgage Lending Discrimination: A Review of Existing Evidence. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute.

United States Census Bureau. (2020). Quick Facts: Omaha city, Nebraska. United States Census Bureau. Accessed December 8, 2022. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/omahacitynebraska.

Walker, Richard. (2022). New Deal Basics - Living New Deal. Accessed December 8, 2022. https://livingnewdeal.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/New-Deal-in-Brief.pdf.

“1865 In Omaha: A Momentous Year - Omaha World-Herald.” (2022). Accessed December 8, 2022. https://omaha.com/special_sections/1865-in-omaha-a-momentous-year/article_72e950df-ec1f-53ae-b383-8ef47b8241fc.html.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2022). U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Accessed December 9, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/.

Chudacoff, Howard P. (1972). Mobile Americans: Residential and Social Mobility in Omaha ; 1880-1920. New York: Oxford Univ. Press.

Certini, Giamoco, and Scalenghe, Riccardo. (2011). Anthropogenic soils are the golden spikes for the Anthropocene. Sage Publications.

David Hendee / World-Herald staff writer. (2019). 1865 In Omaha: A Momentous Year. Omaha World-Herald. Accessed October 16, 2022. https://omaha.com/special_sections/in-omaha-a-momentous-year/article_72e950df-ec1f-53ae-b383-8ef47b8241fc.html.

Doug Thomas / World-Herald staff writer. (2019). Omaha's Once-Sprawling Streetcar System Now Lives Only in Memory. Omaha World-Herald. Accessed October 16, 2022. https://www.omaha.com/living/omaha-s-once-sprawling-streetcar-system-now-lives-only-in/article_faf152c0-da05-11e7-b045-2f378c682fd5.html.

Fletcher, Adam F.C., and Sam Swanson. (2022). A History of Streetcars in Benson. North Omaha History. Accessed October 21, 2022. https://northomahahistory.com/2017/03/04/benson-motor-company/.

Fletcher, Adam F.C., Wade, Linda, Lee, Steven, Mendicino, Lori, Heeren, Ann Heeren. (2022). A History of the Minne Lusa Historic District in North Omaha. North Omaha History. Accessed October 16, 2022. https://northomahahistory.com/2016/06/24/a-history-of-the-minne-lusa-historic-district-in-north-omaha-nebraska/.

Grimm, Nancy B., David Foster, Peter Groffman, J. Morgan Grove, Charles S. Hopkinson, Knute J. Nadelhoffer, Diane E. Pataki, and Debra PC Peters. (2008). The Changing Landscape: Ecosystem Responses to Urbanization and Pollution Across Climatic and Societal Gradients. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 6, no. 5 (June): 264-272. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20440887

“History of Federal Minimum Wage Rates under the Fair Labor Standards Act, 1938 - 2009.” 2022. United States Department of Labor. Accessed December 9. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/minimum-wage/history/chart.

Knute J. Nadelhoffer, Diane E. Pataki, and Debra PC Peters. (2008). The Changing Landscape: Ecosystem Responses to Urbanization and Pollution Across Climatic and Societal Gradients. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 6, no. 5 (June): 264-272. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20440887

Google. (2022). Omaha, Nebraska. Google maps. Retrieved December 8, 2022, from https://maps.google.com/

Lawrence, Harold. (2007). Upstream Metropolis: An Urban Biography of Omaha and Council Bluffs. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Mapping Inequality. Digital Scholarship Lab. (n.d.). Retrieved November 3, 2022, from https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/#loc=12/41.271/-95.991&city=omaha-ne

Mason, R.J., & Nigmatullina, L. (2011). Suburbanization and Sustainability in Metropolitan Moscow. Geographical Review, 101(3), 316–333. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41303637

Nebraska Department of Energy and Environment. (2020). Nebraska Energy Statistics: Nebraska Motor Vehicle Registrations. Nebraska Energy Office, Lincoln, NE. Accessed December 8, 2022. https://neo.ne.gov/programs/stats/inf/72a.html

Nebraska Department of Motor Vehicles, Lincoln, NE. (n.d.). DMV Annual Report. Nebraska Energy Office, Lincoln, NE.

Nicolaides, Becky, and Wiese, Andrew. (2017). Suburbanization in the United States after 1945. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History.

Peattie Elia Wilkinson and Susanne George-Bloomfield. (2005). Impertinences : Selected Writings of Elia Peattie a Journalist in the Gilded Age. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Strand, Palma J. (1970). Mirror, Mirror on the Wall...": Reflections on Fairness and Housing in the Omaha Council-Bluffs Region. CDR Home. https://dspace2.creighton.edu/xmlui/handle/10504/110116.

Thavenet, Dennis. (1960). A History of Omaha Public Transportation. DigitalCommons@UNO. Accessed December 9, 2022. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/1467/.

Turner, Margery Austin, and Felicity Skidmore. (1999). Mortgage Lending Discrimination: A Review of Existing Evidence. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute.

United States Census Bureau. (2020). Quick Facts: Omaha city, Nebraska. United States Census Bureau. Accessed December 8, 2022. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/omahacitynebraska.

Walker, Richard. (2022). New Deal Basics - Living New Deal. Accessed December 8, 2022. https://livingnewdeal.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/New-Deal-in-Brief.pdf.

“1865 In Omaha: A Momentous Year - Omaha World-Herald.” (2022). Accessed December 8, 2022. https://omaha.com/special_sections/1865-in-omaha-a-momentous-year/article_72e950df-ec1f-53ae-b383-8ef47b8241fc.html.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2022). U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Accessed December 9, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/.

Rights

The Durham Museum Permanent Collection

Collection

Citation

Clara Coughlan-Smith

Sabrina Morales, “Omaha Streetmap and Guide,” Omaha in the Anthropocene, accessed April 30, 2024, https://steppingintothemap.com/anthropocene/items/show/45.

Embed

Copy the code below into your web page