VHS Tape

Title

VHS Tape

Subject

This is a VHS tape of a 1991 Christmas concert in Omaha. It was donated to the Durham Museum by the Omaha Musician’s Society. This tape serves as a record of people's experience that Christmas in 1991 and many recordings like this one help keep people’s memories alive. This VHS tape connects Omaha’s history to global environmental history because of what VHS was and how it was used. VHS gave people a new way to access and share information. As this technology progressed, people everywhere became able to preserve their lives on tape. VHS is no longer used today but it stands as an example of cycles of consumption and growth during the Anthropocene. Now we have phones and the internet to record and share our experiences but ultimately the modern media appetite is thanks to the humble VHS.

Description

The VHS tape is a significant artifact in Omaha’s environmental history because VHS was an important medium people used to record their lives and preserve the events happening in Omaha. It links Omaha’s environmental history to the global history of the Anthropocene because it was a major step in informatics and consequently, human cultural evolution as it increased the average person’s ability to record and consume information through media. It was used widely to preserve the past, including here in Omaha, as well as around the world.

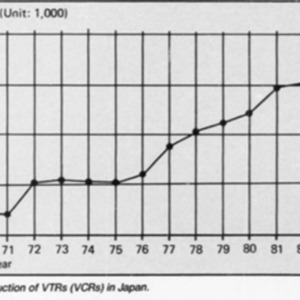

Dating back to their conception, magnetic strip cassette tape recorders were first developed by Ampex in the 1950s for the news media industry (Mix Staff 2011, others). However, it was not until later that VHS arose out of a hard won “format war” in corporate competition with the Betamax format developed by Sony in 1975 (Knight 2015). While bulkier and of lower image quality, VHS ultimately won out over Betamax as the dominant home video system format because of its greater recording duration. VHS was developed by JVC in 1976 and became the leading technology with a majority market share by 1980, for use both by businesses and private households (Knight 2015).

The tape itself consists of plastic and metal pigment layers, “the plastic layer consisting mainly of polyethylene terephthalate” (Pontynen, 2019). PET is the most common polymer used in the production of the various components of a VHS unit. The metal pigment layers supported the analog technicolor capabilities of early VCR sets. The plastic shell of a VHS tape is also of a basic hard plastic; a “semicrystalline thermoplastic that comes from refining petroleum as most all plastics do” (Aslan et al, 1997.). These plastic components of VHS beg their own environmental impact analysis, given the effects of oil refining on the Anthropocene. A majority of plastics are made of fossil fuel hydrocarbons which comes from an industry that has uniquely contributed to the anthropogenic climate crisis to an unequivocal extent. The polymer used is also a very durable form of plastic which makes it more difficult to reuse and recycle. It will not naturally degrade on its own. Despite the materials argument, it is the social impact which has made the VHS such an interesting lens through which to view the Anthropocene.

VHS was a landmark technology especially given its broad availability and novelty to customers across the globe. Counting Betamax too, it was the first readily available means for people to record themselves or the things they experienced for later viewing. Earlier mediums like photography, phonography and silent film could capture reality in one or two dimensions (imagery, audio and time, and imagery and time), but this was the first time imagery, audio, and time were all able to be recorded onto a single analogue record. As explained in the 1992 article “Camcorders'', this technology would put portable recording devices in the hands of anyone who could afford it, at first supporting only the bulky VHS format, but then eventually shrinking down to the more manageable VHS-C format that offered video recording devices that could be operated with one hand weighing in at only 2lbs (“Camcorders'', 1992.)

The artifact we have in particular is a tape recording of a 1991 Christmas Pageant that occurred here in Omaha at the Western Heritage Museum. This object was in the collection at Durham because it was donated by the Omaha Musician’s Association, the tape is titled Merry Tuba Christmas Western Heritage Museum 1991. The Omaha Musician’s society was originally chartered on November 19th, 1897, and has continued to provide music and culture to the Omaha community for 125 years (〖American Federation of Musicians〗^). This particular Christmas concert in Omaha was recorded as a piece of Omaha’s history and how the community gathered together for the holidays and for music.

The VHS tape itself is not especially unique to Omaha’s history. VHS tapes were ways for people temporally or spatially displaced from the actual recorded event to gain or relive experiences both commercially and privately. In particular, the ability to record audio and video dramatically changed the way people experienced music (Mallinder 2015). This is evident here as well, the Christmas concert that was played in Omaha in 1991 is recorded on this tape and to experience it you neither have to time travel nor have been alive in Omaha in 1991. It is a connection to the past for the people of Omaha and a glimpse into life here 30 years ago. This tape is simply an example of thousands like it that were created here in Omaha and of many more like it around the world that are now relics of a previous era. VHS in its time was exceptionally commonplace and could be found in every American’s home (Boucher, 2008).

Although not especially unique due to its ubiquity, VHS was culturally impactful and quickly became a part daily life with commercial movies and home videos. Part of its appeal and rise to popularity was the accessibility of the tapes and the multiplicity of their purpose. VHS allowed people to record and rewatch their favorite shows, games, and events in a way like never before. While this one contains a Christmas concert, going to any thrift store or estate sale around the country, one could find someone's eighth-grade musical from the 80s or a 1979 championship game. The ubiquity of VHS is what solidified its impact and although it finally died its commercial death in 2008, it remains relevant to so many people due to the moments and memories stored on them.

Although VHS was deeply relevant to people around the country, including Omaha, the manufacturing was done elsewhere. This tape was made by Memorex which was a major technology start-up corporation in Silicon Valley. Their products were widely distributed around the world so this was not made in Omaha, but it could easily have been purchased at a Nebraska retailer. The financial impact of VHS in Omaha did not come from production but rather from distribution. Video stores such as Blockbuster, and electronics stores like RadioShack, used to be found all around the city commercially distributing movies and VCR technology. A search through the Yellow Pages reveals that there were once at least nine different video stores in the city of Omaha. They have all since closed. The last reviews on the Saddle Creek Blockbuster were left in 2008 before they shut their doors for good after 32 years in business (C., Crystal, 2008). The death of the VHS was also effectively the death of video stores and the commercial economy of personal media, but this corner of the market was naturally replaced with cellphone stores as the technology passed onto better things.

While they did eventually fade from common use, VHS was once a major form of entertainment and record keeping for people and organizations alike. VHS tapes were used recreationally in two major ways; the first was through home video recordings where people documented special moments in their lives, and the second was for Hollywood. The preservation of the human experience and all it entails such as weddings, concerts, or something as simple as playing with the dog were a part of this first use. The 1982 Memorex commercial's slogan was “Is it live or is it Memorex?” was an attempt to sell customers on the clarity and the vividness of their VHS tapes (Memorex VHS Tapes Ad from 1982). The second way VHS tapes were used recreationally was for entertainment through recorded movies, television, and music. Hollywood mass-produced and distributed its films and recorded its TV series for the public to consume. Either through purchase or rent, VHS tapes became the main form of multimedia consumption at home for many people, being the preferred option to going out to the movies etc. For the people living in the VHS era; “going to the movies meant staying home” (Yue, 2013) and this became an widely popular choice.

Video recording was an important tool occupationally from Hollywood scales to local businesses. VHS allowed movie video productions to make larger profits by selling their films rather than simply playing in theaters. Businesses were also able to record commercials and presentations and distribute those changing marketing practices. New occupations even came about from the invention of VHS ranging from production to television shows like America’s Funniest Home Videos. The tapes are continuing to create new occupational uses as they are recycled and digitized now that their format has gone out of style.

While hotly debated, it’s simple enough to say that the Anthropocene is the accumulated impact of anthropogenic cycles of consumption and production, from the use of wood for the fire that dates back over 120,000 years ago, to the industrialized production paradigm of capitalism. The production paradigm is the notion that cycles of production and consumption are the end goal of a growth oriented self-replicating system. How the VHS is situated in this greater socio-ecological constellation is up to interpretation. VHS tapes can serve as a symbol of technology and industrial capitalism in a western media-based society as it represents the first practical commodification of AV multimedia. As a marvel of western consumerism, it stands conceptually as a ledger, a testament of record, to the happenings of a time of anthropocentric thought and social-economic development as well as to itself (evident in the Memorex commercial being recorded on Memorex). The VHS, a symbol of the 1980s and 90s, represented a global urge to gather, store and disseminate visual information. The VHS was originally developed for use by News agencies but came to represent a ubiquitous item common to all “western” idyllic households. Now it stands as a relic of the mistakes and achievements of a time of rapid global industrialization and commodification.

As referenced in a number of articles (Boucher, 2008. Knight, 2015. Paige, 1998. Verna, 1996. Solheim, 2003. Wloszczyna, 2002.) This is largely an object of the past, albeit the recent past, but the past nonetheless. Sony ceased Betamax equipment production in 2002 (Knight, 2015.) while the best-known date for the end of VHS seems to be 2016 (Walton, 2016.). I think it’s best to say that the historical relationships that link VHS to the Anthropocene have accelerated since its heyday as today media is recorded, shared, and consumed at an unthinkable rate. To demonstrate this point, if you can excuse a brief disregard for formality, I’ll step out of the writing to cite myself as evidence: even I can’t even fully realize how incredible it is that I can just search up topical articles in a heartbeat for the research component of writing this very piece! So, if VHS represents the personalization and commodification of media catered recreationally to individuals, then what we have today with smartphones, YouTube, DVD, and streaming is that same concept on crack, if you’ll excuse my colloquial language.

In some sense the VHS was unique, it was somehow more idealistically pure than the hodgepodge that is contemporary media. It obviously was a commodity that cornered the market that was produced and licensed by private enterprise but, at the same time, it represents something greater today, abstracted from what it physically was, the object itself an artifact of something that has more or less disappeared from the cultural diet. The anthropogenic socioecological connection has infinitely broadened from the product it once was but if we forget the connections it has to the development of the modern media appetite, as a plastic, highly industrialized, commodity good; it still had an impact that may not have disappeared when it ceased to be physically produced. On a different note, one could argue that as long as a single VHS exists out there, the material basis for judging its anthropological importance remains. Plastic is a product of the technology and innovation that has marked the Anthropocene as an anthropogenic (possibly a capital-o-genic) epoch and few things are as idyllically plastic as a VHS tape which is made almost entirely of plastic polymers and can be used, molded, into any shape the user pleases whether it be documentary or a silly video of one’s child playing with their dog. So, this argument that the plastic itself physically has to disappear for the connection to truly be severed, or under the argument that the VHS tape was symbolically plastic (moldable and long lived) made it unique for one reason or another for which reason it hasn’t completely disappeared with its usefulness.

The VHS tape was invented as a direct reaction to capitalism and industrialization. These two themes are very closely related and intertwined throughout the Anthropocene and its many creations and inspirations. The VHS was initially developed and rapidly advanced to fill the consumer need for video technology and information consumption that it could provide (Shiraishi, 1985). The first form of commercial VHS hit the market in 1956 and only 15 years later the technology had advanced from expensive commercial equipment to home video recorders. Just as quickly as it rose though, VHS tapes would fall out of favor to be replaced by DVDs and later streaming (Yue, 2013). These fast-paced changes are a result of the consumer-driven capitalistic society which is always looking to advance and find the next best thing.

This mass production and distribution of the VHS is also related to the Anthropocene in its own way. The materials that make up VHS and the production process were costly both financially and environmentally. The tapes are made up of plastics formed from polyester resins (Aslan, 1997). Plastic production has undoubtedly had a major impact on the environment. The plastics in the VHS were chemically synthesized and, as a result, tend to be difficult to recycle leading to pollutant factors on both ends. The production of the resins also results in carbon outputs which contributed to the carbon-climate crisis we face today. The mass production and subsequent decline of VHS tapes is evidence of cyclical obsolescence, which is a critical component of the production paradigm of the Anthropocene.

This VHS tape is a representation of both human culture and innovation. Industrialization and technological advancements made it possible for its invention. On the other hand, its practical use in the media and in individual homes made it a valuable means of record keeping and sentimental value. This is connected to the Anthropocene because it changed the way humans interacted with each other with the addition of personal recordings and a societal shift to multimedia. These same kind of records also contributed to the global economies and capitalist infrastructures of the present which today drive the ongoing global environmental impact of humans and consequently the Anthropocene.

Dating back to their conception, magnetic strip cassette tape recorders were first developed by Ampex in the 1950s for the news media industry (Mix Staff 2011, others). However, it was not until later that VHS arose out of a hard won “format war” in corporate competition with the Betamax format developed by Sony in 1975 (Knight 2015). While bulkier and of lower image quality, VHS ultimately won out over Betamax as the dominant home video system format because of its greater recording duration. VHS was developed by JVC in 1976 and became the leading technology with a majority market share by 1980, for use both by businesses and private households (Knight 2015).

The tape itself consists of plastic and metal pigment layers, “the plastic layer consisting mainly of polyethylene terephthalate” (Pontynen, 2019). PET is the most common polymer used in the production of the various components of a VHS unit. The metal pigment layers supported the analog technicolor capabilities of early VCR sets. The plastic shell of a VHS tape is also of a basic hard plastic; a “semicrystalline thermoplastic that comes from refining petroleum as most all plastics do” (Aslan et al, 1997.). These plastic components of VHS beg their own environmental impact analysis, given the effects of oil refining on the Anthropocene. A majority of plastics are made of fossil fuel hydrocarbons which comes from an industry that has uniquely contributed to the anthropogenic climate crisis to an unequivocal extent. The polymer used is also a very durable form of plastic which makes it more difficult to reuse and recycle. It will not naturally degrade on its own. Despite the materials argument, it is the social impact which has made the VHS such an interesting lens through which to view the Anthropocene.

VHS was a landmark technology especially given its broad availability and novelty to customers across the globe. Counting Betamax too, it was the first readily available means for people to record themselves or the things they experienced for later viewing. Earlier mediums like photography, phonography and silent film could capture reality in one or two dimensions (imagery, audio and time, and imagery and time), but this was the first time imagery, audio, and time were all able to be recorded onto a single analogue record. As explained in the 1992 article “Camcorders'', this technology would put portable recording devices in the hands of anyone who could afford it, at first supporting only the bulky VHS format, but then eventually shrinking down to the more manageable VHS-C format that offered video recording devices that could be operated with one hand weighing in at only 2lbs (“Camcorders'', 1992.)

The artifact we have in particular is a tape recording of a 1991 Christmas Pageant that occurred here in Omaha at the Western Heritage Museum. This object was in the collection at Durham because it was donated by the Omaha Musician’s Association, the tape is titled Merry Tuba Christmas Western Heritage Museum 1991. The Omaha Musician’s society was originally chartered on November 19th, 1897, and has continued to provide music and culture to the Omaha community for 125 years (〖American Federation of Musicians〗^). This particular Christmas concert in Omaha was recorded as a piece of Omaha’s history and how the community gathered together for the holidays and for music.

The VHS tape itself is not especially unique to Omaha’s history. VHS tapes were ways for people temporally or spatially displaced from the actual recorded event to gain or relive experiences both commercially and privately. In particular, the ability to record audio and video dramatically changed the way people experienced music (Mallinder 2015). This is evident here as well, the Christmas concert that was played in Omaha in 1991 is recorded on this tape and to experience it you neither have to time travel nor have been alive in Omaha in 1991. It is a connection to the past for the people of Omaha and a glimpse into life here 30 years ago. This tape is simply an example of thousands like it that were created here in Omaha and of many more like it around the world that are now relics of a previous era. VHS in its time was exceptionally commonplace and could be found in every American’s home (Boucher, 2008).

Although not especially unique due to its ubiquity, VHS was culturally impactful and quickly became a part daily life with commercial movies and home videos. Part of its appeal and rise to popularity was the accessibility of the tapes and the multiplicity of their purpose. VHS allowed people to record and rewatch their favorite shows, games, and events in a way like never before. While this one contains a Christmas concert, going to any thrift store or estate sale around the country, one could find someone's eighth-grade musical from the 80s or a 1979 championship game. The ubiquity of VHS is what solidified its impact and although it finally died its commercial death in 2008, it remains relevant to so many people due to the moments and memories stored on them.

Although VHS was deeply relevant to people around the country, including Omaha, the manufacturing was done elsewhere. This tape was made by Memorex which was a major technology start-up corporation in Silicon Valley. Their products were widely distributed around the world so this was not made in Omaha, but it could easily have been purchased at a Nebraska retailer. The financial impact of VHS in Omaha did not come from production but rather from distribution. Video stores such as Blockbuster, and electronics stores like RadioShack, used to be found all around the city commercially distributing movies and VCR technology. A search through the Yellow Pages reveals that there were once at least nine different video stores in the city of Omaha. They have all since closed. The last reviews on the Saddle Creek Blockbuster were left in 2008 before they shut their doors for good after 32 years in business (C., Crystal, 2008). The death of the VHS was also effectively the death of video stores and the commercial economy of personal media, but this corner of the market was naturally replaced with cellphone stores as the technology passed onto better things.

While they did eventually fade from common use, VHS was once a major form of entertainment and record keeping for people and organizations alike. VHS tapes were used recreationally in two major ways; the first was through home video recordings where people documented special moments in their lives, and the second was for Hollywood. The preservation of the human experience and all it entails such as weddings, concerts, or something as simple as playing with the dog were a part of this first use. The 1982 Memorex commercial's slogan was “Is it live or is it Memorex?” was an attempt to sell customers on the clarity and the vividness of their VHS tapes (Memorex VHS Tapes Ad from 1982). The second way VHS tapes were used recreationally was for entertainment through recorded movies, television, and music. Hollywood mass-produced and distributed its films and recorded its TV series for the public to consume. Either through purchase or rent, VHS tapes became the main form of multimedia consumption at home for many people, being the preferred option to going out to the movies etc. For the people living in the VHS era; “going to the movies meant staying home” (Yue, 2013) and this became an widely popular choice.

Video recording was an important tool occupationally from Hollywood scales to local businesses. VHS allowed movie video productions to make larger profits by selling their films rather than simply playing in theaters. Businesses were also able to record commercials and presentations and distribute those changing marketing practices. New occupations even came about from the invention of VHS ranging from production to television shows like America’s Funniest Home Videos. The tapes are continuing to create new occupational uses as they are recycled and digitized now that their format has gone out of style.

While hotly debated, it’s simple enough to say that the Anthropocene is the accumulated impact of anthropogenic cycles of consumption and production, from the use of wood for the fire that dates back over 120,000 years ago, to the industrialized production paradigm of capitalism. The production paradigm is the notion that cycles of production and consumption are the end goal of a growth oriented self-replicating system. How the VHS is situated in this greater socio-ecological constellation is up to interpretation. VHS tapes can serve as a symbol of technology and industrial capitalism in a western media-based society as it represents the first practical commodification of AV multimedia. As a marvel of western consumerism, it stands conceptually as a ledger, a testament of record, to the happenings of a time of anthropocentric thought and social-economic development as well as to itself (evident in the Memorex commercial being recorded on Memorex). The VHS, a symbol of the 1980s and 90s, represented a global urge to gather, store and disseminate visual information. The VHS was originally developed for use by News agencies but came to represent a ubiquitous item common to all “western” idyllic households. Now it stands as a relic of the mistakes and achievements of a time of rapid global industrialization and commodification.

As referenced in a number of articles (Boucher, 2008. Knight, 2015. Paige, 1998. Verna, 1996. Solheim, 2003. Wloszczyna, 2002.) This is largely an object of the past, albeit the recent past, but the past nonetheless. Sony ceased Betamax equipment production in 2002 (Knight, 2015.) while the best-known date for the end of VHS seems to be 2016 (Walton, 2016.). I think it’s best to say that the historical relationships that link VHS to the Anthropocene have accelerated since its heyday as today media is recorded, shared, and consumed at an unthinkable rate. To demonstrate this point, if you can excuse a brief disregard for formality, I’ll step out of the writing to cite myself as evidence: even I can’t even fully realize how incredible it is that I can just search up topical articles in a heartbeat for the research component of writing this very piece! So, if VHS represents the personalization and commodification of media catered recreationally to individuals, then what we have today with smartphones, YouTube, DVD, and streaming is that same concept on crack, if you’ll excuse my colloquial language.

In some sense the VHS was unique, it was somehow more idealistically pure than the hodgepodge that is contemporary media. It obviously was a commodity that cornered the market that was produced and licensed by private enterprise but, at the same time, it represents something greater today, abstracted from what it physically was, the object itself an artifact of something that has more or less disappeared from the cultural diet. The anthropogenic socioecological connection has infinitely broadened from the product it once was but if we forget the connections it has to the development of the modern media appetite, as a plastic, highly industrialized, commodity good; it still had an impact that may not have disappeared when it ceased to be physically produced. On a different note, one could argue that as long as a single VHS exists out there, the material basis for judging its anthropological importance remains. Plastic is a product of the technology and innovation that has marked the Anthropocene as an anthropogenic (possibly a capital-o-genic) epoch and few things are as idyllically plastic as a VHS tape which is made almost entirely of plastic polymers and can be used, molded, into any shape the user pleases whether it be documentary or a silly video of one’s child playing with their dog. So, this argument that the plastic itself physically has to disappear for the connection to truly be severed, or under the argument that the VHS tape was symbolically plastic (moldable and long lived) made it unique for one reason or another for which reason it hasn’t completely disappeared with its usefulness.

The VHS tape was invented as a direct reaction to capitalism and industrialization. These two themes are very closely related and intertwined throughout the Anthropocene and its many creations and inspirations. The VHS was initially developed and rapidly advanced to fill the consumer need for video technology and information consumption that it could provide (Shiraishi, 1985). The first form of commercial VHS hit the market in 1956 and only 15 years later the technology had advanced from expensive commercial equipment to home video recorders. Just as quickly as it rose though, VHS tapes would fall out of favor to be replaced by DVDs and later streaming (Yue, 2013). These fast-paced changes are a result of the consumer-driven capitalistic society which is always looking to advance and find the next best thing.

This mass production and distribution of the VHS is also related to the Anthropocene in its own way. The materials that make up VHS and the production process were costly both financially and environmentally. The tapes are made up of plastics formed from polyester resins (Aslan, 1997). Plastic production has undoubtedly had a major impact on the environment. The plastics in the VHS were chemically synthesized and, as a result, tend to be difficult to recycle leading to pollutant factors on both ends. The production of the resins also results in carbon outputs which contributed to the carbon-climate crisis we face today. The mass production and subsequent decline of VHS tapes is evidence of cyclical obsolescence, which is a critical component of the production paradigm of the Anthropocene.

This VHS tape is a representation of both human culture and innovation. Industrialization and technological advancements made it possible for its invention. On the other hand, its practical use in the media and in individual homes made it a valuable means of record keeping and sentimental value. This is connected to the Anthropocene because it changed the way humans interacted with each other with the addition of personal recordings and a societal shift to multimedia. These same kind of records also contributed to the global economies and capitalist infrastructures of the present which today drive the ongoing global environmental impact of humans and consequently the Anthropocene.

Creator

Donald Brorson

Victoria Farrington

Victoria Farrington

Source

Aslan, S, B. Immirzi, P. Laurienzo, M. Malinconico, E. Martuscelli, M. G. Volpe, M. Pelino, and L. Savini. “Unsaturated Polyester Resins from Glycolysed Waste Polyethyleneterephthalate: Synthesis and Comparison of Properties and Performance with Virgin Resin.” Journal of Materials Science 32, no. 9 (May 1997): 2329–36. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1018584519173.

Boucher, Geoff. “VHS Era Is Winding Down.” Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times, December 22, 2008. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2008-dec-22-et-vhs-tapes22-story.html.

“Camcorders.” 1992. Consumer Reports 57 (3): 161–69. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=aph&AN=9204131129&site=ehost-live.

C., Crystal, and nape9393. “Blockbuster - Closed in Omaha , NE.” YP.com, June 4, 2008. https://www.yellowpages.com/omaha-ne/mip/blockbuster-4821900.

Knight, Shawn. “Sony Finally Decides It's Time to Kill Betamax.” TechSpot. TechSpot, November 10, 2015. https://www.techspot.com/news/62733-sony-finally-decides-time-kill-betamax.html.

Mallinder, S. “Live or Memorex? Changing Perceptions of Music Practices.” The Digital Evolution of Live Music, July 28, 2015, 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-08-100067-0.00005-1.

Memorex VHS Tapes Ad from 1982 - Is It Live Or Is It Memorex? YouTube. YouTube,

2008. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EZyFcJcZiaU.

Mix Staff. “1956: Ampex VRX-1000 First Commercial Video Recorder.” Mixonline, January 1, 2011. https://www.mixonline.com/technology/1956-ampex-vrx-1000-first-commercial-video-recorder-383723.

Myers, Fred, and Lisa Stefanoff. “‘We Never Had Any Photos of My Family’: Archival Return, Film, and a Personal History.” Language Documentation and Conservation Volume Special, no. Issue 18 (2020): 217–38.

"Visual Deficiencies of Digitized Analog Video-a Study of a Video Home System (VHS) Archive.".

“Omaha Musicians' Association.” Local 70-558 - Omaha Musicians' Association :: Official Website of the American Federation of Musicians. Accessed November 3, 2022. https://members.afm.org/locals/info/number/70-558.

Paige, Earl. “Used-Tape Business Flourishes.” Billboard 110, no. 22, May 30, 1998.

Pöntynen, Simo. “Chemical Recycling of Magnetic Tape.” LUTPub, January 1, 2019. https://lutpub.lut.fi/handle/10024/160223.

“The Rise and Fall of the VHS.” Southtree. Accessed November 3, 2022. https://southtree.com/blogs/artifact/the-rise-and-fall-of-the-vhs.

Sawyer, T., R. Anderson, and G. McCuaig. 1986. "Is it Live Or is it Memorex?". doi:10.1145/324239.324295.

Shiraishi, Yuma. “History of Home Videotape Recorder Development.” SMPTE Journal 94, no. 12 (December 1985): 1257–63. https://doi.org/10.5594/j03317.

Solheim, Mark K., and Joan Goldwasser. 2003. “From Grooves to Gigabytes.” Kiplinger’s Personal Finance 57 (9): 98. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=aph&AN=10515105&site=ehost-live.

Verna, Paul. “`No Format Reigns Forever,' but Tape's Future Is by No Means a Wrap.” Billboard, July 13, 1996, Vol. 108 edition, sec. Issue 28.

Walton, Mark. “Last Known VCR Maker Stops Production, 40 Years after VHS Format Launch.” Ars Technica, July 21, 2016. https://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2016/07/vcr-vhs-production-ends/.

Whiteman, W. and B. Mathews. 2007. "Is it Real Or is it Memorex: A Distance Learning Experience."

Wloszczyna, Susan. “VHS Is so Familiar, It Can Be Scary.” USA Today. October 15, 2002.

Yue, Genevieve. “Book Review: Killer Tapes and Shattered Screens: Video Spectatorship from VHS to File Sharing.” Film Quarterly 67, no. 1 (2013): 91–92. https://doi.org/10.1525/fq.2013.67.1.91.

Boucher, Geoff. “VHS Era Is Winding Down.” Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times, December 22, 2008. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2008-dec-22-et-vhs-tapes22-story.html.

“Camcorders.” 1992. Consumer Reports 57 (3): 161–69. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=aph&AN=9204131129&site=ehost-live.

C., Crystal, and nape9393. “Blockbuster - Closed in Omaha , NE.” YP.com, June 4, 2008. https://www.yellowpages.com/omaha-ne/mip/blockbuster-4821900.

Knight, Shawn. “Sony Finally Decides It's Time to Kill Betamax.” TechSpot. TechSpot, November 10, 2015. https://www.techspot.com/news/62733-sony-finally-decides-time-kill-betamax.html.

Mallinder, S. “Live or Memorex? Changing Perceptions of Music Practices.” The Digital Evolution of Live Music, July 28, 2015, 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-08-100067-0.00005-1.

Memorex VHS Tapes Ad from 1982 - Is It Live Or Is It Memorex? YouTube. YouTube,

2008. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EZyFcJcZiaU.

Mix Staff. “1956: Ampex VRX-1000 First Commercial Video Recorder.” Mixonline, January 1, 2011. https://www.mixonline.com/technology/1956-ampex-vrx-1000-first-commercial-video-recorder-383723.

Myers, Fred, and Lisa Stefanoff. “‘We Never Had Any Photos of My Family’: Archival Return, Film, and a Personal History.” Language Documentation and Conservation Volume Special, no. Issue 18 (2020): 217–38.

"Visual Deficiencies of Digitized Analog Video-a Study of a Video Home System (VHS) Archive.".

“Omaha Musicians' Association.” Local 70-558 - Omaha Musicians' Association :: Official Website of the American Federation of Musicians. Accessed November 3, 2022. https://members.afm.org/locals/info/number/70-558.

Paige, Earl. “Used-Tape Business Flourishes.” Billboard 110, no. 22, May 30, 1998.

Pöntynen, Simo. “Chemical Recycling of Magnetic Tape.” LUTPub, January 1, 2019. https://lutpub.lut.fi/handle/10024/160223.

“The Rise and Fall of the VHS.” Southtree. Accessed November 3, 2022. https://southtree.com/blogs/artifact/the-rise-and-fall-of-the-vhs.

Sawyer, T., R. Anderson, and G. McCuaig. 1986. "Is it Live Or is it Memorex?". doi:10.1145/324239.324295.

Shiraishi, Yuma. “History of Home Videotape Recorder Development.” SMPTE Journal 94, no. 12 (December 1985): 1257–63. https://doi.org/10.5594/j03317.

Solheim, Mark K., and Joan Goldwasser. 2003. “From Grooves to Gigabytes.” Kiplinger’s Personal Finance 57 (9): 98. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=aph&AN=10515105&site=ehost-live.

Verna, Paul. “`No Format Reigns Forever,' but Tape's Future Is by No Means a Wrap.” Billboard, July 13, 1996, Vol. 108 edition, sec. Issue 28.

Walton, Mark. “Last Known VCR Maker Stops Production, 40 Years after VHS Format Launch.” Ars Technica, July 21, 2016. https://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2016/07/vcr-vhs-production-ends/.

Whiteman, W. and B. Mathews. 2007. "Is it Real Or is it Memorex: A Distance Learning Experience."

Wloszczyna, Susan. “VHS Is so Familiar, It Can Be Scary.” USA Today. October 15, 2002.

Yue, Genevieve. “Book Review: Killer Tapes and Shattered Screens: Video Spectatorship from VHS to File Sharing.” Film Quarterly 67, no. 1 (2013): 91–92. https://doi.org/10.1525/fq.2013.67.1.91.

Rights

The Durham Museum Permanent Collection

Collection

Citation

Donald Brorson

Victoria Farrington, “VHS Tape,” Omaha in the Anthropocene, accessed April 19, 2024, https://steppingintothemap.com/anthropocene/items/show/44.

Embed

Copy the code below into your web page