Branding Iron

Title

Branding Iron

Subject

Branding irons marked cattle ownership. Ranchers used brands on the Great Plains to prevent theft or miscommunication. This is indicative of an era when producers and consumers of beef spread across vast distances. The iron is not specific to a ranch but symbolizes changes in the cattle economy during the 19th and 20th centuries. As demand for red meat grew- the supply could not keep up. Sources of meat grew more distant. Foreign environments came to feed American appetites and similar changes took place around the world. Shipping meat across distances hides its economic and environmental costs. These costs do not disappear but become a dept paid by future consumers and the planet. This branding iron symbolizes the relationship in the Anthropocene.

Description

While a device that was created to permanently burn cattle with an identifying symbol may not sound important in relation to the environment, that isn’t actually the case. The branding iron may not seem like a lot at first glance, but in reality, it is an important artifact in not only Omaha’s environmental history, but also global environmental history. This is because it serves as a symbol of the significance of the cattle ranching industry. The cattle ranching industry has had major effects on not only the environment in Nebraska and the rest of the United States, but the world environment as well. The demand for red meat in the United States accelerated the cattle ranching industry. As the consumer demand for meat rose- the requirement of materials to produce beef, such as pastureland, laborers, feed, all increased exponentially. These concerns were addressed by outsourcing red meat production, which has led to food production becoming more environmentally impactful. This same phenomenon took place worldwide and has created the global food web that we have present in today’s society. Therefore, the branding iron, while relatively small, symbolizes the large effect that its industry has had on global history and therefore the Anthropocene.

Branding cattle is necessary on ranches to differentiate between two herds that share the same grazing space (Lombard 226). Brands are also useful when it comes to preventing the theft of livestock, as a permanent mark on the animal would make it impossible for anyone to try to claim it as their own, if the brand doesn’t belong to them (“Livestock Brands”). These brands often represent the owners “character” given there are no requirements for the symbols to represent anything specific such as the name of the ranch or owner, though they should be decently simple and recognizable (“Livestock Brands”). Once a brand is designed it can be registered for in states that have brand registers, so long as it is a unique symbol that no other ranch is using, which can be difficult to achieve due to the large number of existing brands (“Livestock Brands”). Due to the fact that not all states register their brands and the fact that there is no national brand registration book, it is difficult to determine both where our brand comes from. The simplicity of the branding iron has allowed for it to be used for centuries; however it also makes dating our branding iron problematic as there have seemingly been little changes to the structure of the branding iron since its introduction to the New World (“Livestock Brands”). The brand itself appears to be intact, though the exact symbol may not be obvious. While it appears to be a lowercase “h”, which is what the Durham Museum describes it as, brands are typically composed of capital letters, which means that it is possible that our brand depicts something other than a “h” (“Livestock Brands”). Branding symbols can also be made up of multiple characters or pictures, with brands today often being made of at least three symbols due to the number of existing brands, this means that our brand may not be one symbol, but multiple combined together to make one picture that happens to look like an lowercase “h” (“Livestock Brands”). It is a little humorous that something that was created to assist with identification can be so hard to identify, but the value that the branding iron holds as a symbol of anthropogenic environmental change is still clear.

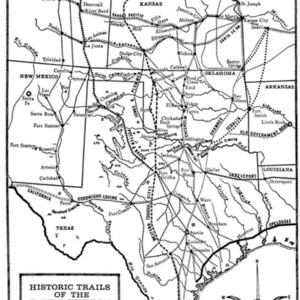

Branding irons in general played an important role in the history of cattle ranching. The origin of cattle branding can be traced back to Egypt in 2700 B.C., but it made its way to the New World from Europe because of Hernando Cortez in 1541 (“Livestock Brands”) This happened because many Spanish and Portuguese colonies in Latin America participated with cattle ranching, and their techniques would have eventually been observed by Texans due to their proximity and eventually adopted by them (“The Origin” 122). The original brands from Spain tended to be complicated with beautiful designs, which made them not very practical, leading to American ranchers to create brands that were more simplistic, easy to remember and produce, while also being effective and difficult to change (“Livestock Brands”). When cattle ranching first became prominent in the United States it was primarily in the Texas and California areas (“The Overemphasis” 2). While ranchers from both areas tried to get their ranching methods spread across the country, with Texas targeting the Great Plains and California the Great Basin neither method lasted past the end of the nineteenth century (“The Overemphasis” 9). At that point a new cattle ranching culture started to rise in popularity, this being the midwestern system of cattle ranching. This new system originated in the Midwest and mountain South, and primarily deviated from the ranching culture in Texas and California with its use of methods originating from the British highlands, instead of ones of Spanish influence (“The Overemphasis” 9). The midwestern system also tended to have more of a focus on the welfare of the cattle and had practices in place that helped the cattle survive through winters and harsh weather, while the Texas and California systems didn’t (“The Overemphasis” 9). This system can be traced back to the 1850s, specifically in Nebraska with its “road ranches” that were set up along the trails, but it only started to spread across the country after the collapse of the Texas and California systems, both of which happened around the 1880s (“The Overemphasis” 12). With the midwest system of cattle ranching being the most popular by the end of the nineteenth century, it would eventually be the system that most ranchers or future ranchers would adapt once they moved out west for the new opportunities that were promised to them by the United States following the Civil War.

The end of the Civil War in the United States opened opportunities for Euro-American settlers to move out West. The United States Government incentivized people to move with the Homestead Act of 1862 that allowed for any US citizen to claim 160 acres of land (Homestead Act). The act had requirements of “improving” the land in the first five years, but the Homestead Act was very indistinct about how the land had to change in order to meet these requirements. Individuals and companies began abusing The Homestead Act, for economic and personal gain, and by the end of 1934 10% of all US lands were distributed into individual hands (Potter 360). These lands were not the US government’s to distribute however- the vast majority of them were inhabited by Native peoples, with established communities, hunting practices and lifestyles (Pritzke 8). The Homestead Act did not account for this and there was a mass displacement of Native peoples in a violent manner. This led to conflict throughout the country as Natives defended their homes, this time period is known as the Indian Wars (Michno 364). As Euro-Americans started occupying this land, the native bison were seen as a nuisance, untamable, and most importantly not profitable (Hornaday 457). Moving forward the bison were killed off in order for the preferred bovine cattle to take their place (Hornaday 466). There was lots of new business in the West including mining, farming, and cattle ranching (Kivette 177). The colonial practices that encouraged a complete change in landscape and lifestyle by displacing the current ecosystems made the ideal conditions for cattle ranching to thrive.

Cattle ranching had lots of potential because during the Civil War, the populations of cattle in Texas had gone unchecked and were now substantially large (Russel 6). The cattle were unbranded as well, making them easy targets for theft (Gard 1). Cattle are not suited for every climate, they require large grazing areas and moderate temperatures which can be seen throughout the central and northern plains, making it seemingly ideal for cattle ranches. (Kim 112). However, cattle also required moving each season to keep the grass plentiful and the cattle alive through the winter (Niedringhaus 18). This led to the development of a rotational grazing system for cattle ranches (Niedringhaus 20). Cattle ranching also requires immense amounts of resources to be brought in such as feed, laborers, ranching equipment, and more (Beef Checkoff 9). The ranching system along with many other emerging economic systems, all needed an efficient way to receive goods quickly- and the answer was the railroad system (Kinbacher 194). The Pacific Railroad Act in 1862 marked the creation of the largest rail system in the US, one that started construction in Omaha, Nebraska (Pacific Railroad Act). The formation of this railroad was the start of a new transportation method that accelerated the production and consumer market. The terminal end in Omaha meant numerous economic opportunities for development, and at one point in the mid-20th century Omaha had the largest stockyards in the country (Kivett 178). Once the basics of cattle ranching were understood and the optimal conditions were met, cattle ranching could flourish into the start of the 20th century.

By the start of the 20th century, cattle ranching was an economic powerhouse, and all the kinks had worked out in order to create the most profit per carcass. In 1909 the US was producing 6,915 million pounds of beef alone each year and imported a mere 2 million (USDA). This mass production of meat was creating a sudden availability of red meat on the market, which made the everyday consumer more eager to consume red meat (Holecheck 119). The US kept up with the demand for red meat until the start of the first World War (Holecheck 118). The war meant less men to work, and more mouths to feed each day. This was the first time that the US decided to outsource their meat production and open the trade doors for the beef to come from non-domestic lands, in 1914 the US imported 328 million pounds of beef compared to 45 million pounds the year before (USDA). The importation of beef slowed down dramatically after the end of the first world war and the American government encouraged the consumer to buy from a local source and support their hometown (Hulse 681). Then came the second World War, and with it another loss of the working class, creating a lack of red meat on the market. And in response the United States had a second uptake in beef imports. In the final year of the war, 1945, the US imported 130 million pounds of beef, and the very next year only imported 20 million pounds (USDA). This lull in imports did not last long however, in 1958 the United States established trade routes with Australia, Canada, and many others. This was in order to establish a constant red meat supply to US consumers and that year imported 1,184 million pounds of beef (USDA). After the United States had created the precedent of getting their meat from somewhere else, they got used to letting someone else do the work for them.

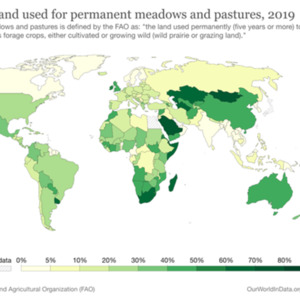

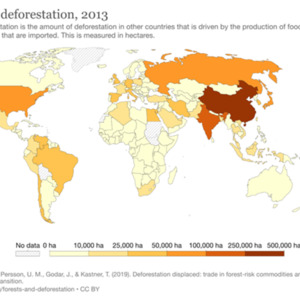

The United States shipped the process of red meat production globally, but the costs did not disappear. The costs were instead paid by the planet, and other less wealthy countries (Ritchie 4). The exportation of this process played a key role in the destruction of world's forests becoming graze lands, as the time period of 1900 to present was when 23% of all natural surviving forests surviving on earth were converted to agricultural land-including crops and grazing land (Ritchie 5). This led to the creation of a global food web, allowing consumers to eat a cow that was butchered all the way across the world for dinner and not know any different (Boucher 45). However ignorant the consumer may be, the costs of outsourcing are innumerable and environmentally deleterious. The impacts of a global food web are compounding, and the price tag when purchasing a package of red meat from the grocery store does not include how many trees were cut down in order to allow that cow to graze (Dubay 2). Now that food is no longer being consumed on a local scale, there are transportation emissions, refrigeration processes, and added preservation stops along the way that all create a negative effect on the environment (Dubay 3). This shift from locally sourced beef to global food webs created a massive impact on our planet that can be seen here in the US and all over the world.

Even though we might not know that many specific history or details about this branding iron, we know that the branding iron symbolizes the cattle ranching industry and the effects that it has had on Omaha and global history. The popularity of the cattle ranching industry helped to put Omaha on the map due to the industry’s reliance on railroad systems like Union Pacific and it helped give Omaha some of the biggest stockyards in the country. Globally the cattle ranching industry spread once it essentially got too big for the United States, who turned to outsourcing to keep up with the demand for red meat. This outsourcing would have large effects on the global environment which can still be seen and added on to today. As the population grows the need for red meat most likely will too, which would logically mean that the global environment and therefore the Anthropocene will continue to be affected by cattle ranching, or in a way, the branding iron.

Branding cattle is necessary on ranches to differentiate between two herds that share the same grazing space (Lombard 226). Brands are also useful when it comes to preventing the theft of livestock, as a permanent mark on the animal would make it impossible for anyone to try to claim it as their own, if the brand doesn’t belong to them (“Livestock Brands”). These brands often represent the owners “character” given there are no requirements for the symbols to represent anything specific such as the name of the ranch or owner, though they should be decently simple and recognizable (“Livestock Brands”). Once a brand is designed it can be registered for in states that have brand registers, so long as it is a unique symbol that no other ranch is using, which can be difficult to achieve due to the large number of existing brands (“Livestock Brands”). Due to the fact that not all states register their brands and the fact that there is no national brand registration book, it is difficult to determine both where our brand comes from. The simplicity of the branding iron has allowed for it to be used for centuries; however it also makes dating our branding iron problematic as there have seemingly been little changes to the structure of the branding iron since its introduction to the New World (“Livestock Brands”). The brand itself appears to be intact, though the exact symbol may not be obvious. While it appears to be a lowercase “h”, which is what the Durham Museum describes it as, brands are typically composed of capital letters, which means that it is possible that our brand depicts something other than a “h” (“Livestock Brands”). Branding symbols can also be made up of multiple characters or pictures, with brands today often being made of at least three symbols due to the number of existing brands, this means that our brand may not be one symbol, but multiple combined together to make one picture that happens to look like an lowercase “h” (“Livestock Brands”). It is a little humorous that something that was created to assist with identification can be so hard to identify, but the value that the branding iron holds as a symbol of anthropogenic environmental change is still clear.

Branding irons in general played an important role in the history of cattle ranching. The origin of cattle branding can be traced back to Egypt in 2700 B.C., but it made its way to the New World from Europe because of Hernando Cortez in 1541 (“Livestock Brands”) This happened because many Spanish and Portuguese colonies in Latin America participated with cattle ranching, and their techniques would have eventually been observed by Texans due to their proximity and eventually adopted by them (“The Origin” 122). The original brands from Spain tended to be complicated with beautiful designs, which made them not very practical, leading to American ranchers to create brands that were more simplistic, easy to remember and produce, while also being effective and difficult to change (“Livestock Brands”). When cattle ranching first became prominent in the United States it was primarily in the Texas and California areas (“The Overemphasis” 2). While ranchers from both areas tried to get their ranching methods spread across the country, with Texas targeting the Great Plains and California the Great Basin neither method lasted past the end of the nineteenth century (“The Overemphasis” 9). At that point a new cattle ranching culture started to rise in popularity, this being the midwestern system of cattle ranching. This new system originated in the Midwest and mountain South, and primarily deviated from the ranching culture in Texas and California with its use of methods originating from the British highlands, instead of ones of Spanish influence (“The Overemphasis” 9). The midwestern system also tended to have more of a focus on the welfare of the cattle and had practices in place that helped the cattle survive through winters and harsh weather, while the Texas and California systems didn’t (“The Overemphasis” 9). This system can be traced back to the 1850s, specifically in Nebraska with its “road ranches” that were set up along the trails, but it only started to spread across the country after the collapse of the Texas and California systems, both of which happened around the 1880s (“The Overemphasis” 12). With the midwest system of cattle ranching being the most popular by the end of the nineteenth century, it would eventually be the system that most ranchers or future ranchers would adapt once they moved out west for the new opportunities that were promised to them by the United States following the Civil War.

The end of the Civil War in the United States opened opportunities for Euro-American settlers to move out West. The United States Government incentivized people to move with the Homestead Act of 1862 that allowed for any US citizen to claim 160 acres of land (Homestead Act). The act had requirements of “improving” the land in the first five years, but the Homestead Act was very indistinct about how the land had to change in order to meet these requirements. Individuals and companies began abusing The Homestead Act, for economic and personal gain, and by the end of 1934 10% of all US lands were distributed into individual hands (Potter 360). These lands were not the US government’s to distribute however- the vast majority of them were inhabited by Native peoples, with established communities, hunting practices and lifestyles (Pritzke 8). The Homestead Act did not account for this and there was a mass displacement of Native peoples in a violent manner. This led to conflict throughout the country as Natives defended their homes, this time period is known as the Indian Wars (Michno 364). As Euro-Americans started occupying this land, the native bison were seen as a nuisance, untamable, and most importantly not profitable (Hornaday 457). Moving forward the bison were killed off in order for the preferred bovine cattle to take their place (Hornaday 466). There was lots of new business in the West including mining, farming, and cattle ranching (Kivette 177). The colonial practices that encouraged a complete change in landscape and lifestyle by displacing the current ecosystems made the ideal conditions for cattle ranching to thrive.

Cattle ranching had lots of potential because during the Civil War, the populations of cattle in Texas had gone unchecked and were now substantially large (Russel 6). The cattle were unbranded as well, making them easy targets for theft (Gard 1). Cattle are not suited for every climate, they require large grazing areas and moderate temperatures which can be seen throughout the central and northern plains, making it seemingly ideal for cattle ranches. (Kim 112). However, cattle also required moving each season to keep the grass plentiful and the cattle alive through the winter (Niedringhaus 18). This led to the development of a rotational grazing system for cattle ranches (Niedringhaus 20). Cattle ranching also requires immense amounts of resources to be brought in such as feed, laborers, ranching equipment, and more (Beef Checkoff 9). The ranching system along with many other emerging economic systems, all needed an efficient way to receive goods quickly- and the answer was the railroad system (Kinbacher 194). The Pacific Railroad Act in 1862 marked the creation of the largest rail system in the US, one that started construction in Omaha, Nebraska (Pacific Railroad Act). The formation of this railroad was the start of a new transportation method that accelerated the production and consumer market. The terminal end in Omaha meant numerous economic opportunities for development, and at one point in the mid-20th century Omaha had the largest stockyards in the country (Kivett 178). Once the basics of cattle ranching were understood and the optimal conditions were met, cattle ranching could flourish into the start of the 20th century.

By the start of the 20th century, cattle ranching was an economic powerhouse, and all the kinks had worked out in order to create the most profit per carcass. In 1909 the US was producing 6,915 million pounds of beef alone each year and imported a mere 2 million (USDA). This mass production of meat was creating a sudden availability of red meat on the market, which made the everyday consumer more eager to consume red meat (Holecheck 119). The US kept up with the demand for red meat until the start of the first World War (Holecheck 118). The war meant less men to work, and more mouths to feed each day. This was the first time that the US decided to outsource their meat production and open the trade doors for the beef to come from non-domestic lands, in 1914 the US imported 328 million pounds of beef compared to 45 million pounds the year before (USDA). The importation of beef slowed down dramatically after the end of the first world war and the American government encouraged the consumer to buy from a local source and support their hometown (Hulse 681). Then came the second World War, and with it another loss of the working class, creating a lack of red meat on the market. And in response the United States had a second uptake in beef imports. In the final year of the war, 1945, the US imported 130 million pounds of beef, and the very next year only imported 20 million pounds (USDA). This lull in imports did not last long however, in 1958 the United States established trade routes with Australia, Canada, and many others. This was in order to establish a constant red meat supply to US consumers and that year imported 1,184 million pounds of beef (USDA). After the United States had created the precedent of getting their meat from somewhere else, they got used to letting someone else do the work for them.

The United States shipped the process of red meat production globally, but the costs did not disappear. The costs were instead paid by the planet, and other less wealthy countries (Ritchie 4). The exportation of this process played a key role in the destruction of world's forests becoming graze lands, as the time period of 1900 to present was when 23% of all natural surviving forests surviving on earth were converted to agricultural land-including crops and grazing land (Ritchie 5). This led to the creation of a global food web, allowing consumers to eat a cow that was butchered all the way across the world for dinner and not know any different (Boucher 45). However ignorant the consumer may be, the costs of outsourcing are innumerable and environmentally deleterious. The impacts of a global food web are compounding, and the price tag when purchasing a package of red meat from the grocery store does not include how many trees were cut down in order to allow that cow to graze (Dubay 2). Now that food is no longer being consumed on a local scale, there are transportation emissions, refrigeration processes, and added preservation stops along the way that all create a negative effect on the environment (Dubay 3). This shift from locally sourced beef to global food webs created a massive impact on our planet that can be seen here in the US and all over the world.

Even though we might not know that many specific history or details about this branding iron, we know that the branding iron symbolizes the cattle ranching industry and the effects that it has had on Omaha and global history. The popularity of the cattle ranching industry helped to put Omaha on the map due to the industry’s reliance on railroad systems like Union Pacific and it helped give Omaha some of the biggest stockyards in the country. Globally the cattle ranching industry spread once it essentially got too big for the United States, who turned to outsourcing to keep up with the demand for red meat. This outsourcing would have large effects on the global environment which can still be seen and added on to today. As the population grows the need for red meat most likely will too, which would logically mean that the global environment and therefore the Anthropocene will continue to be affected by cattle ranching, or in a way, the branding iron.

Creator

Bridget Courtney

Elise Gooding-Lord

Elise Gooding-Lord

Source

Act of May 20, 1862 (Homestead Act), Public Law 37-64 (12 STAT 392); 5/20/1862; Enrolled Acts and Resolutions of Congress, 1789 - 2011; General Records of the United States Government, Record Group 11; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/homestead-act, November 18, 2022]

Act of July 1, 1862 (Pacific Railroad Act), (12 STAT 489); 7/1/1862; Enrolled Acts and Resolutions of Congress, 1789 - 2011; General Records of the United States Government, Record Group 11; National Archives Building, Washington, DC.

Anderson, Bruce. “Grasslands and Forages of Nebraska.”Rangelands, vol. 21, no. 1, 1999, pp.5–8. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4001500. Accessed 6 Oct. 2022.

Beef Checkoff. “Quality Care and Handling Guidelines.” Beef Quality Assurance.

Boucher, Doug, et al. “Cattle and Pasture.” The Root of the Problem: What’s Driving Tropical Deforestation Today, Union of Concerned Scientists, 2011, pp. 41–49. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep00075.11. Accessed 3 Nov. 2022.

Dubay, Adrianna, et al. The Water Footprint of Livestock | Mathematics of Sustainability. 16 Sept. 2018, muse.union.edu/mth-063-01-f18/2018/09/16/the-water-footprint-of-livestock.

Gard, Wayne. “The Impact of the Cattle Trails.” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, vol. 71, no. 1, 1967, pp. 1–6. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30237939. Accessed 3 Nov. 2022.

Haggerty, J. H., M. Auger, and K. Epstein. "Ranching Sustainability in the Northern Great Plains: An Appraisal of Local Perspectives." Rangelands, vol. 40, no. 3, 2018, pp. 83-91. doi:10.1016/j.rala.2018.03.005.

Hiller, Tim L., et al. “Long-Term Agricultural Land Use Trends in Nebraska, 1866—2007.” Great Plains Research, vol. 19, no. 2, 2009, pp. 225–37.http://www.jstor.org/stable/23780131. Accessed 3 Nov. 2022.

Holechek, Jerry L., et al. “Macro Economics and Cattle Ranching.” Rangelands, vol. 16, no. 3, 1994, pp. 118–23. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4001044. Accessed 1 Nov. 2022.

Hornaday, William Temple. The Extermination of the American Bison. United States, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1889.

Hulse, David, and Robert Ribe. “Land Conversion and the Production of Wealth.” Ecological Applications, vol. 10, no. 3, 2000, pp. 679–82. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2641036. Accessed 1 Nov. 2022.

Iverson, Peter. When Indians Became Cowboys: Native Peoples and Cattle Ranching in the American West. University of Oklahoma Press, 1994.

Jordan, Terry G. “The Origin and Distribution of Open-Range Cattle Ranching.” Social Science Quarterly, vol. 53, no. 1, 1972, pp. 85-92. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42858856. Accessed 6 Oct. 2022.

Jordan, Terry G. "Overemphasis of Texas as a Source of Western Cattle Ranching." (1992). Social Science Quarterly, vol. 53, no. 1, 1972, pp. 105–21. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42858856. Accessed 6 Oct. 2022.

Kim, S., et al. “The Effect of Socioeconomic Factors on the Adoption of Best Management Practices in Beef Cattle Production.” Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, Soil and Water Conservation Society, 1 May 2005, https://www.jswconline.org/content/60/3/111/tab-article-info.

Kivett, Marvin F. “The Nebraska State Historical Society.” History News, vol. 22, no. 8, 1967, pp. 177–79. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42646071. Accessed 1 Nov. 2022.

“Livestock Brands.” Cowboy Showcase, https://www.cowboyshowcase.com/brands.html#.Y2MbUy-B06W.

Lombard, Carol G., and Theodorus Du Plessis. “Beyond the Branding Iron: Cattle Brands as Heritage Place Names in the State of Montana.” Names, vol. 64, no. 4, 2016, pp. 224–233., https://doi.org/10.1080/00277738.2016.1223119.

“Major Land Uses.” USDA ERS - Major Land Uses, https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/major-land-uses/.

Makkar, H P S. “Review: Feed demand landscape and implications of food-not feed strategy for food security and climate change.” Animal : an international journal of animal bioscience vol. 12,8 (2018): 1744-1754. doi:10.1017/S175173111700324X

Michno, Gregory. Encyclopedia of Indian Wars: Western Battles and Skirmishes, 1850-1890. Mountain Press Pub. Co., 2005.

Niedringhaus, Lee I. “The N Bar N Ranch: A Legend of The Open-Range Cattle Industry 18 85-99.” Montana: The Magazine of Western History, vol. 60, no. 1, 2010, pp. 3–92. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25701715. Accessed 2 Nov. 2022.

Potter, Lee Ann and Wynell Schamel. "The Homestead Act of 1862." Social Education 61, 6 (October 1997): 359-364.

Pritzke, Frank. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford University Press, 2000.

Ritchie, Hannah, and Max Roser. “Forests and Deforestation.” Our World in Data, 9 Feb. 2021, ourworldindata.org/forests-and-deforestation.

Russell, John C. “Holding the Herd: Nelson Story’s 1866 Cattle Drive.” Montana: The Magazine of Western History, vol. 68, no. 4, 2018, pp. 4–92. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45200812. Accessed 1 Nov. 2022.

Starrs, Paul F. Let the Cowboy Ride: Cattle Ranching in the American West. Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 2000.

“Texas Cattle Trade in Omaha.” History Nebraska, https://history.nebraska.gov/texas-cattle-trade-in-omaha/.

Thornton, Philip K. “Livestock production: recent trends, future prospects.” Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences vol. 365,1554 (2010): 2853-67. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0134

Union of Concerned Scientists. Cattle, Cleared Forests, and Climate Change: Scoring America’s Top Brands on Their Deforestation-Free Beef Commitments and Practices. Union of Concerned Scientists, 2016. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep17253. Accessed 2 Nov. 2022.

USDA ERS - Food Availability (per Capita) Data System. www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-availability-per-capita-data-system.

USDA ERS - Livestock and Meat International Trade Data. www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/livestock-and-meat-international-trade-data/livestock-and-meat-international-trade-data.

Act of July 1, 1862 (Pacific Railroad Act), (12 STAT 489); 7/1/1862; Enrolled Acts and Resolutions of Congress, 1789 - 2011; General Records of the United States Government, Record Group 11; National Archives Building, Washington, DC.

Anderson, Bruce. “Grasslands and Forages of Nebraska.”Rangelands, vol. 21, no. 1, 1999, pp.5–8. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4001500. Accessed 6 Oct. 2022.

Beef Checkoff. “Quality Care and Handling Guidelines.” Beef Quality Assurance.

Boucher, Doug, et al. “Cattle and Pasture.” The Root of the Problem: What’s Driving Tropical Deforestation Today, Union of Concerned Scientists, 2011, pp. 41–49. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep00075.11. Accessed 3 Nov. 2022.

Dubay, Adrianna, et al. The Water Footprint of Livestock | Mathematics of Sustainability. 16 Sept. 2018, muse.union.edu/mth-063-01-f18/2018/09/16/the-water-footprint-of-livestock.

Gard, Wayne. “The Impact of the Cattle Trails.” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, vol. 71, no. 1, 1967, pp. 1–6. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30237939. Accessed 3 Nov. 2022.

Haggerty, J. H., M. Auger, and K. Epstein. "Ranching Sustainability in the Northern Great Plains: An Appraisal of Local Perspectives." Rangelands, vol. 40, no. 3, 2018, pp. 83-91. doi:10.1016/j.rala.2018.03.005.

Hiller, Tim L., et al. “Long-Term Agricultural Land Use Trends in Nebraska, 1866—2007.” Great Plains Research, vol. 19, no. 2, 2009, pp. 225–37.http://www.jstor.org/stable/23780131. Accessed 3 Nov. 2022.

Holechek, Jerry L., et al. “Macro Economics and Cattle Ranching.” Rangelands, vol. 16, no. 3, 1994, pp. 118–23. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4001044. Accessed 1 Nov. 2022.

Hornaday, William Temple. The Extermination of the American Bison. United States, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1889.

Hulse, David, and Robert Ribe. “Land Conversion and the Production of Wealth.” Ecological Applications, vol. 10, no. 3, 2000, pp. 679–82. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2641036. Accessed 1 Nov. 2022.

Iverson, Peter. When Indians Became Cowboys: Native Peoples and Cattle Ranching in the American West. University of Oklahoma Press, 1994.

Jordan, Terry G. “The Origin and Distribution of Open-Range Cattle Ranching.” Social Science Quarterly, vol. 53, no. 1, 1972, pp. 85-92. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42858856. Accessed 6 Oct. 2022.

Jordan, Terry G. "Overemphasis of Texas as a Source of Western Cattle Ranching." (1992). Social Science Quarterly, vol. 53, no. 1, 1972, pp. 105–21. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42858856. Accessed 6 Oct. 2022.

Kim, S., et al. “The Effect of Socioeconomic Factors on the Adoption of Best Management Practices in Beef Cattle Production.” Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, Soil and Water Conservation Society, 1 May 2005, https://www.jswconline.org/content/60/3/111/tab-article-info.

Kivett, Marvin F. “The Nebraska State Historical Society.” History News, vol. 22, no. 8, 1967, pp. 177–79. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42646071. Accessed 1 Nov. 2022.

“Livestock Brands.” Cowboy Showcase, https://www.cowboyshowcase.com/brands.html#.Y2MbUy-B06W.

Lombard, Carol G., and Theodorus Du Plessis. “Beyond the Branding Iron: Cattle Brands as Heritage Place Names in the State of Montana.” Names, vol. 64, no. 4, 2016, pp. 224–233., https://doi.org/10.1080/00277738.2016.1223119.

“Major Land Uses.” USDA ERS - Major Land Uses, https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/major-land-uses/.

Makkar, H P S. “Review: Feed demand landscape and implications of food-not feed strategy for food security and climate change.” Animal : an international journal of animal bioscience vol. 12,8 (2018): 1744-1754. doi:10.1017/S175173111700324X

Michno, Gregory. Encyclopedia of Indian Wars: Western Battles and Skirmishes, 1850-1890. Mountain Press Pub. Co., 2005.

Niedringhaus, Lee I. “The N Bar N Ranch: A Legend of The Open-Range Cattle Industry 18 85-99.” Montana: The Magazine of Western History, vol. 60, no. 1, 2010, pp. 3–92. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25701715. Accessed 2 Nov. 2022.

Potter, Lee Ann and Wynell Schamel. "The Homestead Act of 1862." Social Education 61, 6 (October 1997): 359-364.

Pritzke, Frank. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford University Press, 2000.

Ritchie, Hannah, and Max Roser. “Forests and Deforestation.” Our World in Data, 9 Feb. 2021, ourworldindata.org/forests-and-deforestation.

Russell, John C. “Holding the Herd: Nelson Story’s 1866 Cattle Drive.” Montana: The Magazine of Western History, vol. 68, no. 4, 2018, pp. 4–92. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45200812. Accessed 1 Nov. 2022.

Starrs, Paul F. Let the Cowboy Ride: Cattle Ranching in the American West. Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 2000.

“Texas Cattle Trade in Omaha.” History Nebraska, https://history.nebraska.gov/texas-cattle-trade-in-omaha/.

Thornton, Philip K. “Livestock production: recent trends, future prospects.” Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences vol. 365,1554 (2010): 2853-67. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0134

Union of Concerned Scientists. Cattle, Cleared Forests, and Climate Change: Scoring America’s Top Brands on Their Deforestation-Free Beef Commitments and Practices. Union of Concerned Scientists, 2016. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep17253. Accessed 2 Nov. 2022.

USDA ERS - Food Availability (per Capita) Data System. www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-availability-per-capita-data-system.

USDA ERS - Livestock and Meat International Trade Data. www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/livestock-and-meat-international-trade-data/livestock-and-meat-international-trade-data.

Rights

The Durham Museum Permanent Collection

Collection

Citation

Bridget Courtney

Elise Gooding-Lord, “Branding Iron,” Omaha in the Anthropocene, accessed April 26, 2024, https://steppingintothemap.com/anthropocene/items/show/43.

Embed

Copy the code below into your web page