Broadhead Axe

Title

Broadhead Axe

Subject

The late nineteenth-century was the great age of railroad construction. In America and around the world, they increased transportation efficiency. Like all industrial processes, railroads required an enormous amount of natural resources. This included wooden planks to hold the rails together. This broad head ax, or one like it, shaped these planks, also known as ax-ties. The amount of wood the railroads needed required wide-scale deforestation. Omaha was an important part of this story. It was the eastern edge of the Transcontinental Railroad and the home of Union Pacific. The rise of railroads drove Omaha’s growth, and the presence of railroads are globally seen. The general use of railroads has declined. The broad ax played a significant role in the establishment of railroads. This is important to the Anthropocene because it symbolizes the effects of industrialization on the environment.

Description

There have been many inventions and innovations throughout human history, but few have been as instrumental to human advancement as the ax. The ax has played a key role in acquiring wood and shaping it for uses besides fire and fuel. There are many different types of axes, and their form follows their function. Felling axes chop down trees, and pickaxes skimming and chopping through roots. The ax in The Durham Museum collection is the broad ax. Broad axes were and are used for hewing wood or turning round logs into more rectangular shapes for building. Our ax was found in the Omaha area, but there is one problem with finding an ax here. Why would an ax be in an area that has historically had few trees? We believe the ax was used to shape logs into small planks, or rail ties. Omaha’s historic role as a center of continental railroad construction justifies this claim. The broadhead ax was instrumental in constructing railroads when the Union Pacific railroad was expanding across the Midwest, and similarly influential to global rail development.

The broad ax was a tool of labor. Many households had access to this tool, and it could also be found at worksites. As seen in Figures 4, 5, and 6, the ax features a very long, or broad, shaped blade. The blade almost looks like a fan, with rounded edges and a narrower base. One side of the blade is a straight, flat edge. The other side of the blade is beveled, meaning that there is a slant in the iron to create a sharp edge. The broad ax in The Durham Museum collection is made of iron, though it is missing its wooden handle. Most broad axes had a shorter handle which would slide entirely though the metal ax head, as seen in Figure 4 (Sloan 2002, 14). The broad ax was a common belonging of early Euro-American settlers. While it was not the ideal tool for felling lumber, it was useful to create wooden beams to structure houses or cabins. The ax operated as a sort of chisel, where the flat edge of the blade drove into the wood, creating a straight edge. The beveled edge would then cut through the excess wood, cleaving it from the straight edge (Sloan 2002, 15).

Nebraska and other states of the Great Plains do not have a large number of trees useful for widespread lumber use. Settlers had to build homes, but the supply of trees was few compared to other states further north or east. However, as white settlers began expanding westward following the Louisiana Purchase, they needed resources and tools in order to build homes. Permanent structures often required square beams, ideally suited to the broad ax. As the settlers moved into what would become Nebraska throughout the first half of the nineteenth-century, small settlements like Council Bluffs, IA and Bellevue, NE took shape. Omaha was established in 1854, and by 1860 had a population of 1,883 (“Population of Nebraska Incorporated Places, 1860 to 1920” 2010). The broad ax was a fundamental tool of this early period of settlement and urbanization.

The broad ax had an even more significant role in Omaha’s history: the construction of railroads. Railways were introduced to the United States in Massachusetts in the early nineteenth-century. While the locomotive steam engine was still being developed, a series of small wooden tramways appeared in the Northeast primarily as a temporary mode of transport for construction or mining (Grant 2005, 2). The first commercial railroad was called the Baltimore and Ohio Railway, founded in 1827 out of Maryland (Previts and Samson 2000, 6) and the first commercial locomotive built in the United States was finished in 1830 in New York (Middleton 1941, 37). By the outbreak of the American Civil War, interest in constructing railroads in the vast interior of the continent gained support. The Union Pacific railroad was the middleman in connecting both sides of the continent by rail. The company started in 1862 and Omaha was its terminus.

In order to have railroads though, you have to have wooden planks for railroad ties (Union Pacific, 2022). With numerous tracks laid, the broad ax surely had widespread use because of rail ties. Ties are wooden boards that are anchored to the earth as a foundation to hold the steel rails. Lumber would be cut into long square slats with the assistance of the broad ax, squaring off the rounded edges of the logs. After being cut, the ties were then dried, ridding them of any moisture and then treated with a wood preservative (Middleton 1941, 20). Railroad construction demanded millions of cross ties, making the production of such items critical for rail’s success (Union Pacific). Beyond railroad construction, railroad maintenance required the replacement of cross ties.

Nebraska and other Great Plains states did not have a ready supply of timber, however. The lumber required to build the railroads likely had to be shipped to Omaha via the Missouri river or nearby small railroads. Finding wood for construction turned out to be one of the biggest problems for the early years of Union Pacific (Union Pacific). Any adequate wood was used, but Cedar trees were primarily chopped down in North Platte and hewn in Wyoming once the railroad made it to those locations (Union Pacific). Those resources sufficed the railroad for a while before they turned to getting their wood from the Pacific Northwest and Canada like they do in today (Union Pacific).

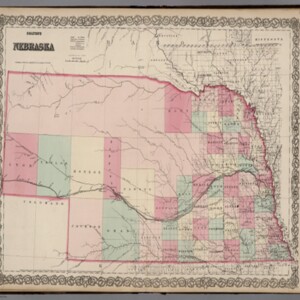

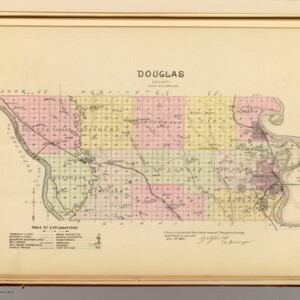

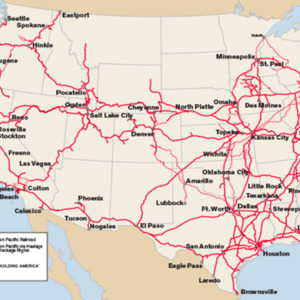

By the 1940s, there were more than a billion cross ties in use across the United States, and millions needed replacement annually (Middleton 1941, 20). Figure 1, which is from 1869, shows the slow start Union Pacific had as it was only able to make 1 track in its first 7 years. We can see there was some more progress as Union Pacific made an additional 4 to 5 tracks between 1869 and 1885; the year Figure 2 was created. Omaha as a city was also shaped by the railroads. The city expanded around the train depots, with the downtown area developing just beyond the railroad for accessibility and convenience. Just as the needs of Union Pacific altered the layout of the city, the population experienced rapid change and development due in part to the rail system. The city grew from less than 2,000 people in 1860 to 16,083 people in 1870, a growth of over 750%. Over the next two decades, the population exploded to 140,452 (“Population of Nebraska Incorporated Places, 1860 to 1920”, 2010). The next 130 years would prove to be prosperous for Union Pacific. The company is now the largest rail company in the country with over 32,000 miles of tracks spanning the western two thirds of the U.S. (Union Pacific). In the process, Union Pacific has also formed relationships with other companies to enhance their shipping capabilities to reach parts of the world beyond their homeland.

For the most part, the Omaha community has benefited from the many railroads that have been laid down. The widespread use of locomotives was a pivotal moment in history for most western societies. Railroads moved people, manufactured goods, and raw materials across the country rapidly, without the labor, livestock, and supporting supplies previously needed for large scale transport (Ellis 1968, 19). Railroads required heavy industry to manufacture the locomotives and steel rails. They also needed large amounts of lumber and coal to lay down the tracks and to fuel the enormous furnaces of commercial engines (Lewis 1998, 81). Railroads were one of Omaha’s earliest industries and created steady jobs for its residents as engineers, support staff, and manual laborers (Peterson, 2011). Some community members most likely handled the broadhead axes themselves when they worked for Union Pacific. The broad ax was used to literally lay the foundations for railroads. But how has humanity's desire for growth impacted its relationship with the environment?

The rail system in the U.S was a key component in our early advancement. Railroads were necessary for transporting large amounts of resources nationally and internationally. Railroads simultaneously connected people with far off lands and made travel easier and far more convenient. As with all human advancement, there have been unforeseen negative consequences in the form of maltreatment and environmental damage. Resources had to be shipped across the country to construct the railroads. This means there has to be large-scale deforestation going on in order to supply railroads with the necessary wood. One company in the Appalachian Mountains chopped down as much as 1,162,900 feet of sawed lumber and 57,749 railroad ties in the span of a year (Lewis, 1998, 43). The Pacific Northwest encountered rapid and reckless deforestation, as seen in Figure 7, which contributed to the erosion of the mountainsides of the Cascade Mountains (Ellis 1968, 139). Additionally, railroads affect the process of deforestation. Railroad systems are used in Siberia to transport lumber from Russian forests to consumers in China. Over 16 million acres of Russian forests were cut in 2018 for economic gain, leading the world in deforestation rates (Kramer 2019).

Railroads have been a prime mover of goods, resources, and people since the nineteenth-century, and thus have served as drivers of anthropogenic changes to the landscape and environment. A myriad of natural resources is needed to construct the railroad tracks, not to mention the large quantity needed to maintain the rail system. The amount of land that has been devoted to railroads and the businesses surrounding railroads is immense, with just under 140,000 miles of tracks in the United States alone (U.S Department of Transportation, 2020). Internationally, “the most basic environmental impact from…rail is the destruction of habitat to create a transportation corridor” (Losos, et al. 2019, 8). Devotion of linear infrastructures like railways directly correlates to rates of deforestation (Losos, et al. 2019, 14). Other parts of the world have been impacted too. In India, much of the deforestation that is seen today can be dated all the way back to the nineteenth-century when railroad construction began (Das 2010, 38). Today there are roughly 67,546 miles of rail on the Indian landscape (Indian Railways, 21). In Europe, the Deutsche Bahn (DB) rail system seems to blanket the continent with 643 million miles of railroads being laid by 2013 (Marketline Industry Profile 2015, 18). Furthermore, it is projected that global rail networks will increase in size because of advancing energy sources (Popp and Boyle 2017). Overall railroad construction has terraformed the surface of the earth to fit the needs of growing consumers.

It therefore promotes the notion of the Capitalocene: a geological change that has been driven by the effects of capitalism. The need for transportation has long been an idea with the notion of profit at the forefront of companies. The siphoning of resources for the sake of economic progress has taken its toll on the earth, a toll that will be seen for many years to come. The iron ax head represents the impact that rail has had on the environment and promotes the notion that humans have changed earth’s natural systems for their own gain.

Since the booming days of railroads and the industrial revolution, axes at large have decreased in use. This is largely in part to human advancement and creating more efficient ways to cut down trees. The mechanization of the world now allows us to befall larger trees at faster rates with less laborers. Now people and corporations use chainsaws or circular saws to cut their railroad ties. Compared to the broadhead ax, this saves a lot of time and increases efficiency. Axes today are commonly used to chop wood for fires or for hobbies. In fact, Ax throwing has become a popular activity across the western world.

While axes are less popular, railways for personal use are more active than ever. In 2019, Amtrak trains carried over 3 and a half million passengers across the United States (Lazo 2019). Subway and elevated rail systems exist within larger cities internationally, moving commuters and tourists. Elsewhere in the world, railroad technology has evolved to use metal tracks, thereby eliminating the need for the broadhead ax. High-speed rail is developing at a rapid rate, allowing people to travel at unthinkably fast speeds. For example, in Japan, there is a passenger rail system that can move people at hundreds of miles per hour, as opposed to the early steam engines which a horse could outrun. Some even argue that railways are a more ecologically conscious form of transportation than cars due to its concentration of access points. If a person can only access trains from spread out points, the population grows around that point and does not spread elsewhere. If they do not go elsewhere, more land is left untouched by humans (Losos et al. 2019, 19). While the hewing ax is no longer common, it is undeniable that it had a major impact when it came to the creation of rail systems across the world, similar to the railroads found here in Omaha.

The broad ax was a tool of labor. Many households had access to this tool, and it could also be found at worksites. As seen in Figures 4, 5, and 6, the ax features a very long, or broad, shaped blade. The blade almost looks like a fan, with rounded edges and a narrower base. One side of the blade is a straight, flat edge. The other side of the blade is beveled, meaning that there is a slant in the iron to create a sharp edge. The broad ax in The Durham Museum collection is made of iron, though it is missing its wooden handle. Most broad axes had a shorter handle which would slide entirely though the metal ax head, as seen in Figure 4 (Sloan 2002, 14). The broad ax was a common belonging of early Euro-American settlers. While it was not the ideal tool for felling lumber, it was useful to create wooden beams to structure houses or cabins. The ax operated as a sort of chisel, where the flat edge of the blade drove into the wood, creating a straight edge. The beveled edge would then cut through the excess wood, cleaving it from the straight edge (Sloan 2002, 15).

Nebraska and other states of the Great Plains do not have a large number of trees useful for widespread lumber use. Settlers had to build homes, but the supply of trees was few compared to other states further north or east. However, as white settlers began expanding westward following the Louisiana Purchase, they needed resources and tools in order to build homes. Permanent structures often required square beams, ideally suited to the broad ax. As the settlers moved into what would become Nebraska throughout the first half of the nineteenth-century, small settlements like Council Bluffs, IA and Bellevue, NE took shape. Omaha was established in 1854, and by 1860 had a population of 1,883 (“Population of Nebraska Incorporated Places, 1860 to 1920” 2010). The broad ax was a fundamental tool of this early period of settlement and urbanization.

The broad ax had an even more significant role in Omaha’s history: the construction of railroads. Railways were introduced to the United States in Massachusetts in the early nineteenth-century. While the locomotive steam engine was still being developed, a series of small wooden tramways appeared in the Northeast primarily as a temporary mode of transport for construction or mining (Grant 2005, 2). The first commercial railroad was called the Baltimore and Ohio Railway, founded in 1827 out of Maryland (Previts and Samson 2000, 6) and the first commercial locomotive built in the United States was finished in 1830 in New York (Middleton 1941, 37). By the outbreak of the American Civil War, interest in constructing railroads in the vast interior of the continent gained support. The Union Pacific railroad was the middleman in connecting both sides of the continent by rail. The company started in 1862 and Omaha was its terminus.

In order to have railroads though, you have to have wooden planks for railroad ties (Union Pacific, 2022). With numerous tracks laid, the broad ax surely had widespread use because of rail ties. Ties are wooden boards that are anchored to the earth as a foundation to hold the steel rails. Lumber would be cut into long square slats with the assistance of the broad ax, squaring off the rounded edges of the logs. After being cut, the ties were then dried, ridding them of any moisture and then treated with a wood preservative (Middleton 1941, 20). Railroad construction demanded millions of cross ties, making the production of such items critical for rail’s success (Union Pacific). Beyond railroad construction, railroad maintenance required the replacement of cross ties.

Nebraska and other Great Plains states did not have a ready supply of timber, however. The lumber required to build the railroads likely had to be shipped to Omaha via the Missouri river or nearby small railroads. Finding wood for construction turned out to be one of the biggest problems for the early years of Union Pacific (Union Pacific). Any adequate wood was used, but Cedar trees were primarily chopped down in North Platte and hewn in Wyoming once the railroad made it to those locations (Union Pacific). Those resources sufficed the railroad for a while before they turned to getting their wood from the Pacific Northwest and Canada like they do in today (Union Pacific).

By the 1940s, there were more than a billion cross ties in use across the United States, and millions needed replacement annually (Middleton 1941, 20). Figure 1, which is from 1869, shows the slow start Union Pacific had as it was only able to make 1 track in its first 7 years. We can see there was some more progress as Union Pacific made an additional 4 to 5 tracks between 1869 and 1885; the year Figure 2 was created. Omaha as a city was also shaped by the railroads. The city expanded around the train depots, with the downtown area developing just beyond the railroad for accessibility and convenience. Just as the needs of Union Pacific altered the layout of the city, the population experienced rapid change and development due in part to the rail system. The city grew from less than 2,000 people in 1860 to 16,083 people in 1870, a growth of over 750%. Over the next two decades, the population exploded to 140,452 (“Population of Nebraska Incorporated Places, 1860 to 1920”, 2010). The next 130 years would prove to be prosperous for Union Pacific. The company is now the largest rail company in the country with over 32,000 miles of tracks spanning the western two thirds of the U.S. (Union Pacific). In the process, Union Pacific has also formed relationships with other companies to enhance their shipping capabilities to reach parts of the world beyond their homeland.

For the most part, the Omaha community has benefited from the many railroads that have been laid down. The widespread use of locomotives was a pivotal moment in history for most western societies. Railroads moved people, manufactured goods, and raw materials across the country rapidly, without the labor, livestock, and supporting supplies previously needed for large scale transport (Ellis 1968, 19). Railroads required heavy industry to manufacture the locomotives and steel rails. They also needed large amounts of lumber and coal to lay down the tracks and to fuel the enormous furnaces of commercial engines (Lewis 1998, 81). Railroads were one of Omaha’s earliest industries and created steady jobs for its residents as engineers, support staff, and manual laborers (Peterson, 2011). Some community members most likely handled the broadhead axes themselves when they worked for Union Pacific. The broad ax was used to literally lay the foundations for railroads. But how has humanity's desire for growth impacted its relationship with the environment?

The rail system in the U.S was a key component in our early advancement. Railroads were necessary for transporting large amounts of resources nationally and internationally. Railroads simultaneously connected people with far off lands and made travel easier and far more convenient. As with all human advancement, there have been unforeseen negative consequences in the form of maltreatment and environmental damage. Resources had to be shipped across the country to construct the railroads. This means there has to be large-scale deforestation going on in order to supply railroads with the necessary wood. One company in the Appalachian Mountains chopped down as much as 1,162,900 feet of sawed lumber and 57,749 railroad ties in the span of a year (Lewis, 1998, 43). The Pacific Northwest encountered rapid and reckless deforestation, as seen in Figure 7, which contributed to the erosion of the mountainsides of the Cascade Mountains (Ellis 1968, 139). Additionally, railroads affect the process of deforestation. Railroad systems are used in Siberia to transport lumber from Russian forests to consumers in China. Over 16 million acres of Russian forests were cut in 2018 for economic gain, leading the world in deforestation rates (Kramer 2019).

Railroads have been a prime mover of goods, resources, and people since the nineteenth-century, and thus have served as drivers of anthropogenic changes to the landscape and environment. A myriad of natural resources is needed to construct the railroad tracks, not to mention the large quantity needed to maintain the rail system. The amount of land that has been devoted to railroads and the businesses surrounding railroads is immense, with just under 140,000 miles of tracks in the United States alone (U.S Department of Transportation, 2020). Internationally, “the most basic environmental impact from…rail is the destruction of habitat to create a transportation corridor” (Losos, et al. 2019, 8). Devotion of linear infrastructures like railways directly correlates to rates of deforestation (Losos, et al. 2019, 14). Other parts of the world have been impacted too. In India, much of the deforestation that is seen today can be dated all the way back to the nineteenth-century when railroad construction began (Das 2010, 38). Today there are roughly 67,546 miles of rail on the Indian landscape (Indian Railways, 21). In Europe, the Deutsche Bahn (DB) rail system seems to blanket the continent with 643 million miles of railroads being laid by 2013 (Marketline Industry Profile 2015, 18). Furthermore, it is projected that global rail networks will increase in size because of advancing energy sources (Popp and Boyle 2017). Overall railroad construction has terraformed the surface of the earth to fit the needs of growing consumers.

It therefore promotes the notion of the Capitalocene: a geological change that has been driven by the effects of capitalism. The need for transportation has long been an idea with the notion of profit at the forefront of companies. The siphoning of resources for the sake of economic progress has taken its toll on the earth, a toll that will be seen for many years to come. The iron ax head represents the impact that rail has had on the environment and promotes the notion that humans have changed earth’s natural systems for their own gain.

Since the booming days of railroads and the industrial revolution, axes at large have decreased in use. This is largely in part to human advancement and creating more efficient ways to cut down trees. The mechanization of the world now allows us to befall larger trees at faster rates with less laborers. Now people and corporations use chainsaws or circular saws to cut their railroad ties. Compared to the broadhead ax, this saves a lot of time and increases efficiency. Axes today are commonly used to chop wood for fires or for hobbies. In fact, Ax throwing has become a popular activity across the western world.

While axes are less popular, railways for personal use are more active than ever. In 2019, Amtrak trains carried over 3 and a half million passengers across the United States (Lazo 2019). Subway and elevated rail systems exist within larger cities internationally, moving commuters and tourists. Elsewhere in the world, railroad technology has evolved to use metal tracks, thereby eliminating the need for the broadhead ax. High-speed rail is developing at a rapid rate, allowing people to travel at unthinkably fast speeds. For example, in Japan, there is a passenger rail system that can move people at hundreds of miles per hour, as opposed to the early steam engines which a horse could outrun. Some even argue that railways are a more ecologically conscious form of transportation than cars due to its concentration of access points. If a person can only access trains from spread out points, the population grows around that point and does not spread elsewhere. If they do not go elsewhere, more land is left untouched by humans (Losos et al. 2019, 19). While the hewing ax is no longer common, it is undeniable that it had a major impact when it came to the creation of rail systems across the world, similar to the railroads found here in Omaha.

Creator

Colton Miller

Hannah Juday

Hannah Juday

Source

Carpenter, T. G. The Environmental Impact of Railways. Chichester, Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, 1994. Colton & co. Nebraska. 1869.

Das, Pallavi. "Colonialism and the Environment in India: Railways and Deforestation in 19th Century Punjab." Journal of Asian and African Studies (Leiden) 46, no. 1 (2011): 38-53.

Dilts, James D. The Great Road: The Building of the Baltimore and Ohio, the Nation's First Railroad, 1828-1853. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1993.

Ellis, Hamilton. The Pictorial Encyclopedia of Railways. New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1968. Everts and Kirk. Douglas County. 1885.

“Freight Rail Overview.” Federal Railroad Administration. U.S. Department of Transportation, Last modified July 28, 2020. https://railroads.dot.gov/rail-network-development/freight-rail-overview.

Grant, H. Roger. The Railroad: The Life Story of a Technology. Greenwood Technographies.Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2005.

“Indian Railways: Lifeline to the Nation.” Indian Railways. Ministry of Railways-Railway Board, July 15, 2021. https://indianrailways.gov.in/railwayboard/view_section.jsp?lang=0&id=0%2C1%2C261

Klein, Maury. Union Pacific. 1st ed. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1987.

Kramer, Andrew E. “As the Chinese Cut down Siberia's Forests, Tensions with Russians Rise.” The New York Times. The New York Times Company, July 25, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/25/world/europe/russia-china-siberia-logging.html.

Lazo, Luz. “Amtrak touts record ridership, revenue for fiscal 2019.” The Washington Post. Nash Holdings, November 8, 2019.

Lewis, Ronald L. Transforming the Appalachian Countryside: Railroads, Deforestation, and Social Change in West Virginia, 1880-1920. 1998.

Link, Alessandra. “Editing for Expansion: Railroad Photography, Native Peoples, and the American West, 1860–1880.” Western Historical Quarterly 50, no. 3 (2019): 281–313. https://doi.org/10.1093/whq/whz043.

Losos, Elizabeth, Alexander Pfaff, Lydia Olander, Sara Mason, and Seth Morgan. “Reducing Environmental Risks from Belt and Road Initiative Investments in Transportation Infrastructure.” World Bank Group, January 2019. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/700631548446492003/pdf/WPS8718.pdf.

“Market Line Industry Profile: Railroads in France.” 2014. Railroads Industry Profile: France, January, 1–35. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=bth&AN=95032145&site=ehost-live.

Middleton, P. Harvey. Railways and the Equipment and Supply Industry. 2nd ed. Chicago: Railway Business Association, 1941.

Peterson, Jess. “A Short History of the Early Development of Omaha, Nebraska.” Historic Omaha, (2011). http://www.historicomaha.com/hstrypag.htm#:~:text=Early%20industry%20in%20Omaha%20also,prevention%20and%20water%20delivery%20services.

Popp, J. N., and S. P. Boyle. “Railway Ecology: Underrepresented in Science?” Basic and Applied Ecology 19 (March 2017): 84–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2016.11.006.

“Population of Nebraska Incorporated Places, 1860 to 1920.” Nebraska State Government, (January 13, 2010). https://opportunity.nebraska.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Places-Populations_1860-1920.pdf

Previts, Gary John, and William D. Samson. “Exploring the Contents of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Annual Reports: 1827–1856.” Accounting Historians Journal 27, no. 1 (June 2000): 1–42.

Roberts, J. C. D. “Discursive Destabilization of Socio-Technical Regimes: Negative Storylines and the Discursive Vulnerability of Historical American Railroads.” Energy Research & Social Science 31 (September 2017): 86–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2017.05.031.

Sloane, Eric. A Museum of Early American Tools. Mincola, New York: Dover Publications, 2002.

Union Pacific. Union Pacific System Map. 2022

Union Pacific Railroad. “Station Map of South Omaha. Douglas and Sarpy Counties, Nebraska. P-4003-13.” David Rumsey Historical Map Collection. Cartography Associates, 1945. https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~329418~90097880:Station-Map-of-South-Omaha-Douglas?sort=Pub_List_No_InitialSort%2CPub_Date%2CPub_List_No%2CSeries_No&qvq=q%3AOmaha%3Bsort%3APub_List_No_InitialSort%2CPub_Date%2CPub_List_No%2CSeries_No%3Blc%3ARUMSEY~8~1&mi=3&trs=125.

Das, Pallavi. "Colonialism and the Environment in India: Railways and Deforestation in 19th Century Punjab." Journal of Asian and African Studies (Leiden) 46, no. 1 (2011): 38-53.

Dilts, James D. The Great Road: The Building of the Baltimore and Ohio, the Nation's First Railroad, 1828-1853. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1993.

Ellis, Hamilton. The Pictorial Encyclopedia of Railways. New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1968. Everts and Kirk. Douglas County. 1885.

“Freight Rail Overview.” Federal Railroad Administration. U.S. Department of Transportation, Last modified July 28, 2020. https://railroads.dot.gov/rail-network-development/freight-rail-overview.

Grant, H. Roger. The Railroad: The Life Story of a Technology. Greenwood Technographies.Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2005.

“Indian Railways: Lifeline to the Nation.” Indian Railways. Ministry of Railways-Railway Board, July 15, 2021. https://indianrailways.gov.in/railwayboard/view_section.jsp?lang=0&id=0%2C1%2C261

Klein, Maury. Union Pacific. 1st ed. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1987.

Kramer, Andrew E. “As the Chinese Cut down Siberia's Forests, Tensions with Russians Rise.” The New York Times. The New York Times Company, July 25, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/25/world/europe/russia-china-siberia-logging.html.

Lazo, Luz. “Amtrak touts record ridership, revenue for fiscal 2019.” The Washington Post. Nash Holdings, November 8, 2019.

Lewis, Ronald L. Transforming the Appalachian Countryside: Railroads, Deforestation, and Social Change in West Virginia, 1880-1920. 1998.

Link, Alessandra. “Editing for Expansion: Railroad Photography, Native Peoples, and the American West, 1860–1880.” Western Historical Quarterly 50, no. 3 (2019): 281–313. https://doi.org/10.1093/whq/whz043.

Losos, Elizabeth, Alexander Pfaff, Lydia Olander, Sara Mason, and Seth Morgan. “Reducing Environmental Risks from Belt and Road Initiative Investments in Transportation Infrastructure.” World Bank Group, January 2019. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/700631548446492003/pdf/WPS8718.pdf.

“Market Line Industry Profile: Railroads in France.” 2014. Railroads Industry Profile: France, January, 1–35. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=bth&AN=95032145&site=ehost-live.

Middleton, P. Harvey. Railways and the Equipment and Supply Industry. 2nd ed. Chicago: Railway Business Association, 1941.

Peterson, Jess. “A Short History of the Early Development of Omaha, Nebraska.” Historic Omaha, (2011). http://www.historicomaha.com/hstrypag.htm#:~:text=Early%20industry%20in%20Omaha%20also,prevention%20and%20water%20delivery%20services.

Popp, J. N., and S. P. Boyle. “Railway Ecology: Underrepresented in Science?” Basic and Applied Ecology 19 (March 2017): 84–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2016.11.006.

“Population of Nebraska Incorporated Places, 1860 to 1920.” Nebraska State Government, (January 13, 2010). https://opportunity.nebraska.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Places-Populations_1860-1920.pdf

Previts, Gary John, and William D. Samson. “Exploring the Contents of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Annual Reports: 1827–1856.” Accounting Historians Journal 27, no. 1 (June 2000): 1–42.

Roberts, J. C. D. “Discursive Destabilization of Socio-Technical Regimes: Negative Storylines and the Discursive Vulnerability of Historical American Railroads.” Energy Research & Social Science 31 (September 2017): 86–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2017.05.031.

Sloane, Eric. A Museum of Early American Tools. Mincola, New York: Dover Publications, 2002.

Union Pacific. Union Pacific System Map. 2022

Union Pacific Railroad. “Station Map of South Omaha. Douglas and Sarpy Counties, Nebraska. P-4003-13.” David Rumsey Historical Map Collection. Cartography Associates, 1945. https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~329418~90097880:Station-Map-of-South-Omaha-Douglas?sort=Pub_List_No_InitialSort%2CPub_Date%2CPub_List_No%2CSeries_No&qvq=q%3AOmaha%3Bsort%3APub_List_No_InitialSort%2CPub_Date%2CPub_List_No%2CSeries_No%3Blc%3ARUMSEY~8~1&mi=3&trs=125.

Rights

The Durham Museum Permanent Collection

Collection

Citation

Colton Miller

Hannah Juday, “Broadhead Axe,” Omaha in the Anthropocene, accessed April 20, 2024, https://steppingintothemap.com/anthropocene/items/show/47.

Embed

Copy the code below into your web page