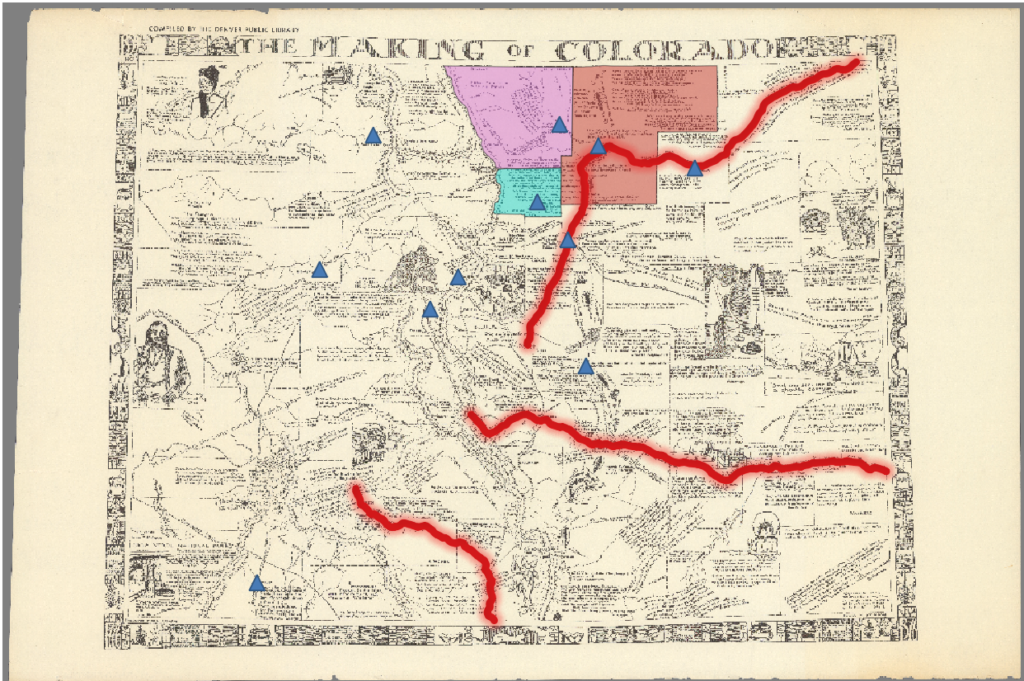

In my final project, I will seek to answer the following question: How rapid was population growth in mining boom towns built near newly discovered deposits of precious metals and minerals in Colorado’s Rocky Mountains in the 1800s? Did the type of mineral or precious metal mined near a mining boom town and a mining boom town’s ease-of-access by roads, trails, or waterways impact the rate of population increase they experienced?

In the 1800s in Colorado, white settlers in the Rocky Mountains found deposits of gold, silver, lead, and other valuable metals that caused an influx of white settlers into what is now the Colorado Rocky Mountains. [1] This massive influx of immigrants and settlers hoping to strike it rich by mining precious metals and minerals in the Rockies created numerous mining boom towns whose population growth rates exploded. One of these boom towns, Leadville, grew so large that when the Territory of Colorado was applying for statehood in 1876 it was the second most populous city in the state. [2]

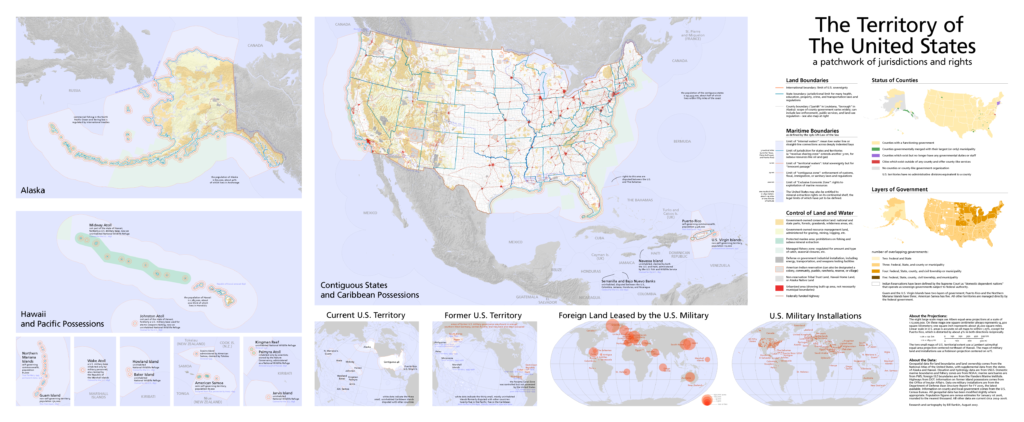

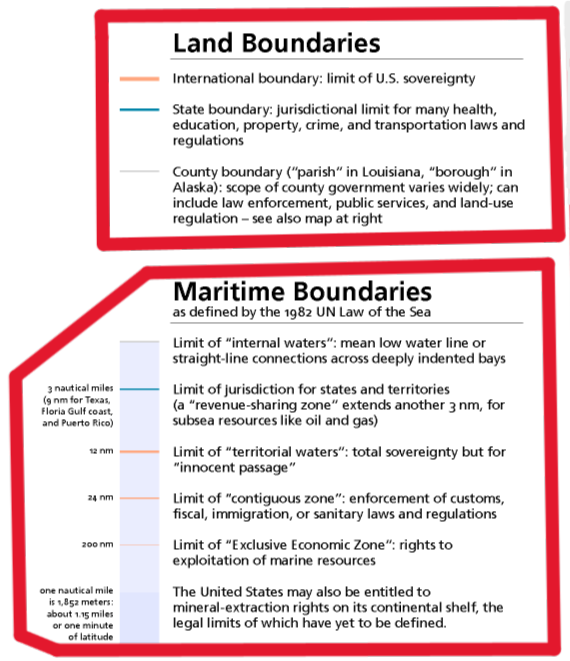

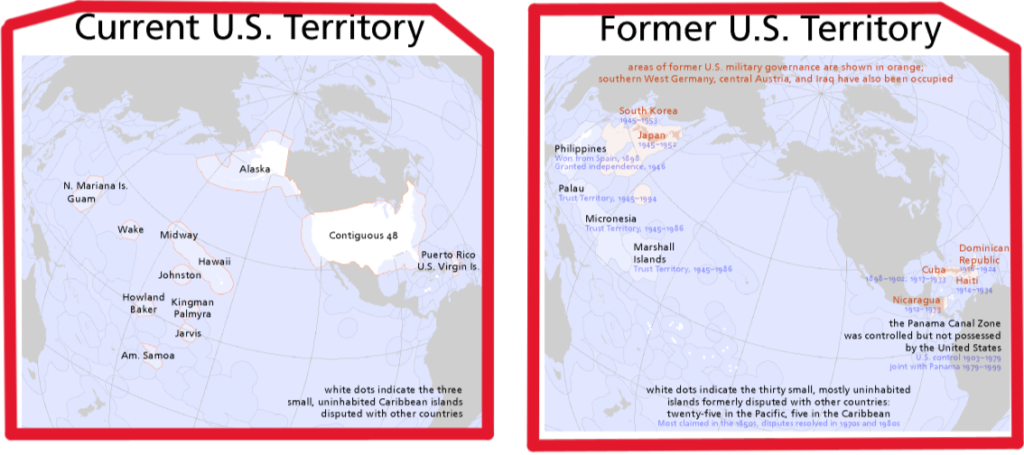

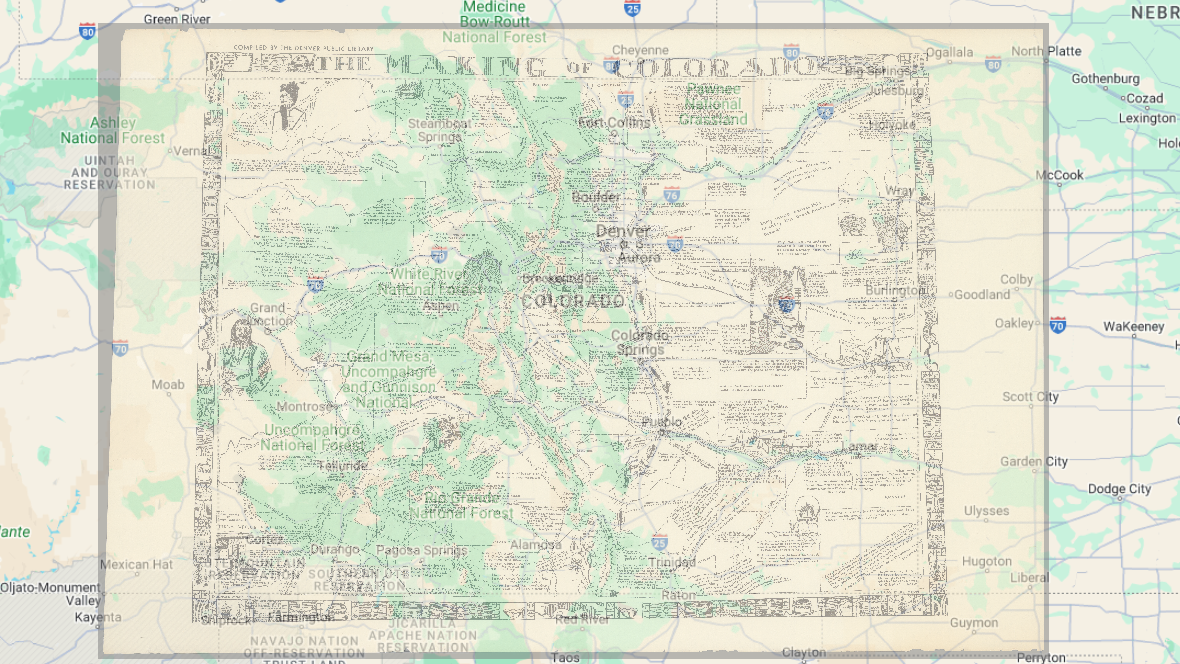

However, particularly in the 1800s, the Rocky Mountains were a challenging place to traverse. Peaks thousands of feet high rise above canyons that dip into the shadows of those frigid, treeless peaks. Roads in the Rockies today often take somewhat winding routes through canyons, valleys, and tunnels which remain difficult to traverse and maintain today. In the 1800s the road, trail, and waterway networks in the Rocky Mountains were certainly not as efficient or developed as they are today providing an extreme challenge to settlers hoping to penetrate into the mountainous interior of the state. For this reason, I want to investigate whether mining boom towns that were located near the eastern edge of the Rockies or in other easier-to-access locales attracted larger numbers of migrants and settlers which in turn increased their population growth. Additionally, I want to investigate whether the type of mineral or precious metal mined near these boom towns led more migrants and settlers to move to certain boom towns despite their potentially difficult-to-reach locations. To analyze this, I will investigate and map census records of the Territory and State of Colorado, mining districts and mineral and precious metal deposits in the state, road and navigable waterway network maps of Colorado in the 1800s, topographic maps of the Rocky Mountains, and possibly diaries or journals kept by settlers which I can use to analyze how they chose where to settle and the travel challenges they faced along the way.

Bibliography

[1] Colorado Geological Survey, “Metals,” Colorado Geological Survey, accessed Feb. 27, 2024, https://coloradogeologicalsurvey.org/minerals/metals/.

[2] Trevor Mark, “Was Leadville Almost the State Capital?” Herald Democrat (Leadville, CO), Nov. 8, 2017. https://www.leadvilleherald.com/news/article_0276a8c6-c4ba-11e7-a26a-4fa814987988.html