In the US today, there is little to no land that is not currently serving a purpose. By this, I mean that nearly every acre is allocated to something: farming, homes, parks, state parks, cities, and all in between. Even land that has seemingly no function, is usually placed within a conservation easement of some sort; therefore, serving a purpose. However, in the time of Elam Bartholomew this was not the case. The prairies served an endless abundance of farmland, once rightfully plowed. Areas they determined were bad for farming, were mowed or left for grazing/hay. This was common:

Geoff Cunfer, “Pasture and Plows,” On the Great Plains, 2005; 19

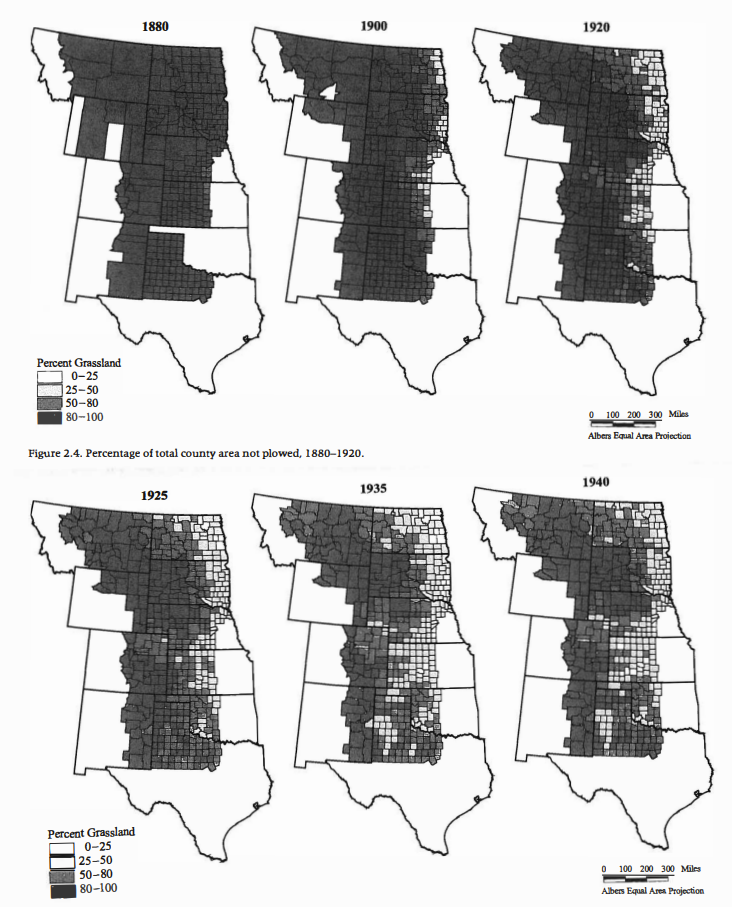

Across the entire Great Plains, this transformation of natural grasses to pastures and farming was occurring: in what one described as the “most important ecological action” (Cunfer 17). Most importantly, the farmers discovered the natural limits of nature: something I believe science takes advantage of today. From 1880 to 1920, you can see the slow and tedious process of turning grassland into agricultural land:

Figure 2.4. Percentage of total county area not plowed, 1880-1920.

The eastern regions were targeted first, with subtle differences in large 20 year increments. Due to increased farming, demand for land, improved technologies, and an improved economy, the next fifteen years created immense change.

Figure 2.5. Percentage of total county area not plowed, 1925-1940.

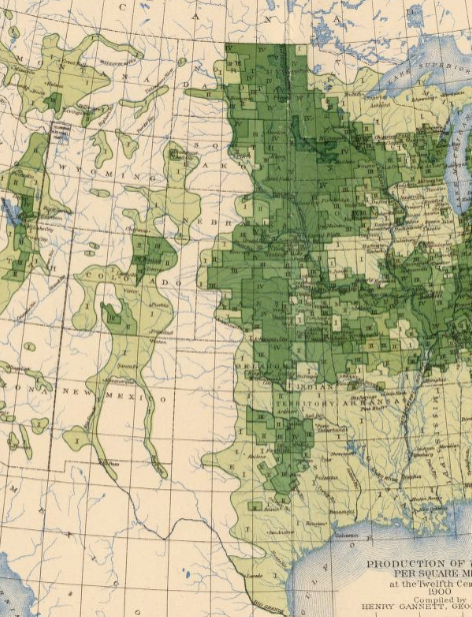

When viewing the 1935 map, the change is greatly shown. The dark black map from the 1880s is now ~⅓ white, denoting 0-25% grassland in these areas (in other words a ~75% decrease in grassland!). By 1940, the resistance/limit set by the land is shown as the grassland returns in some areas. The author uses a choropleth map to maintain his argument, contrasting white and black which allows for an easy interpretation and visual of the change occurring. Sharing a similar argument, the 1903 map of wheat/square mile shows that eastern land was developed first and the Great Plains remained largely untouched until the 20th century.

Henry Gannett, Wheat/sq. mile, 12th census of the US, 1903.

The dark green regions show the most bushels per mile2, while the white/unshaded regions represent the lowest amount of wheat production. Again, the mapmaker uses simple contrasting choropleths to show the argument. If this map were continued into the 1930s to 1940s, I presume it would show the same changes that Cunfers’ maps did–expansion and plowing of the Great Plains. The unshaded regions would become darker as the years passed and farming became more prevalent.