Ecology is not static. Nature changes over time, and the interaction between humans and nature can drive change on a relatively rapid and large scale. Take the example of plowing grassland for agriculture, which Geoff Cunfer equates to “to clear-cutting a forest, but more absolute because the effort to maintain only a single species continues year after year” [1]. The map below implies the extent and magnitude of this changed ecology:

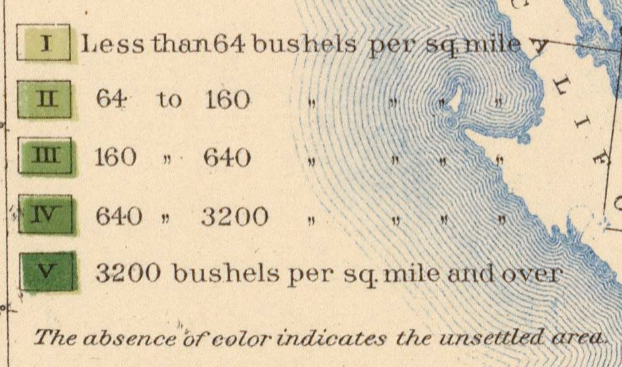

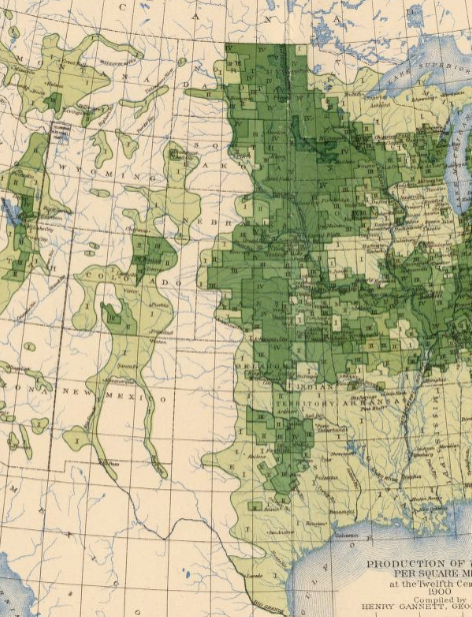

The above map depicts production of wheat per square mile, based on the U.S. Census of 1900. Bushel per square mile is mapped regardless of political boundaries like county or state lines, thus highlighting the direct interaction between humans and nature. However, the map uses data from only one Census, thus presenting the economic activity of wheat production and land use as fixed in time. Compare this to figures from Cunfer’s book:

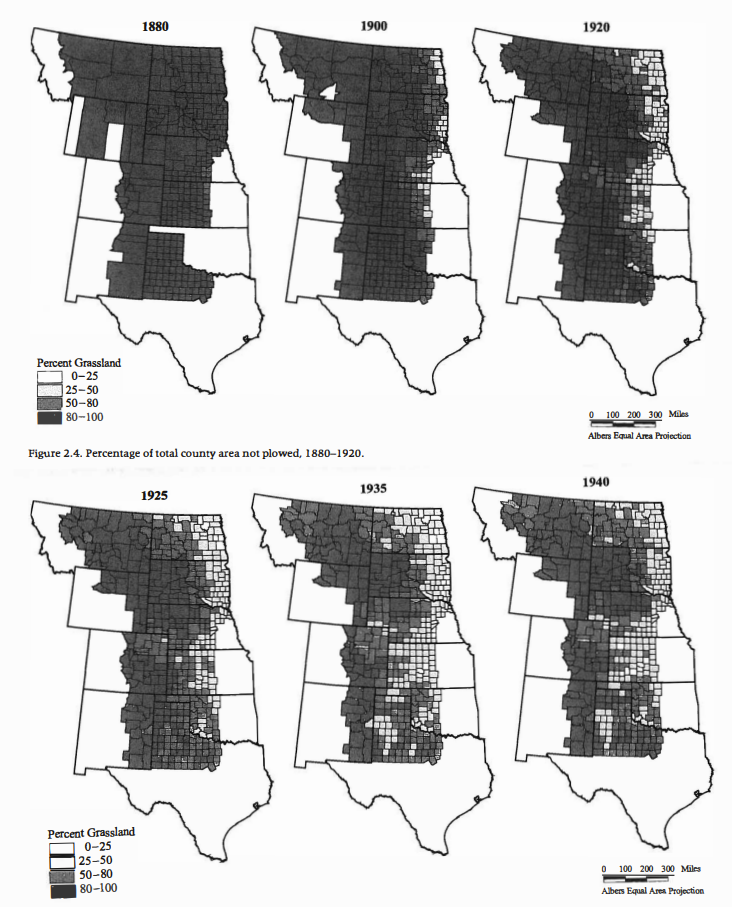

To begin, Cunfer maps humanity’s ecological impact more explicitly by measuring percent of grassland rather than production of wheat. Further, Cunfer takes change over time into account and thus provides a more realistic view of human interaction with the environment. As Cunfer notes in his text, plowing and cultivation in the Great Plains took decades to develop, with the agricultural landscape always shifting due to factors like weather, settlement, and crop markets [3].

Ultimately, Cunfer’s map is both larger and smaller scale than Gannett’s. The final image from the 1900 map depicts the same general region (spanning from Texas to Montana) as Cunfer’s figures. Cunfer’s representation from 1900 showed that most counties were still above 80% grassland, but the Census map reveals that some agriculture and settlement had already begun in many of these same areas. In this sense, Cunfer does not capture the same kind of localized ecological impact as Gannett. However, Gannett’s large vectors of wheat production do not account for the nuances of land use. The amount of wheat producible by a square mile of land can depend on natural factors like climate or soil [4]. Thus, the percentage of grassland plowed by farming could vary considerably between regions that produce the same total amount of wheat. By honing in on the smaller-scale county level land use, Cunfer depicts nuance that goes unincluded by Gannett.

Citation 1-4: Geoff Cunfer, On the Great Plains: Agriculture and Environment, College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2005.

Nicely written and argued Wyatt!