The reading, “Racism in the Machine: Visualization Ethics in Digital Humanities Projects,” by Katherine Hepworth and Christopher Church began its discussion by introducing the problem of neutrality in digital projects. While many things have the perception of neutrality, their structures, choices, and backgrounds come from long-imposed structures of oppression, like racism. Attempting to create a neutral project (especially one generated by AI), will inevitably result in the same problematic structures current society is created on becoming visible and a prominent aspect of those projects. Digital Projects need an argument, or at least some critical intention.

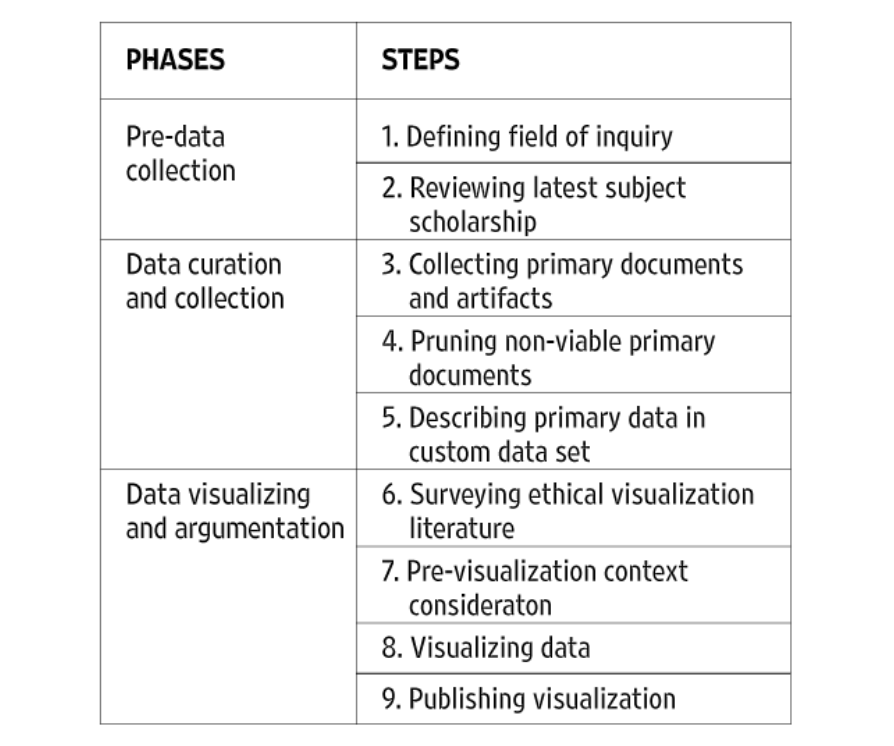

A chart of Hepworth and Church’s outline

Within the argument or critical intention of a digital project, it is important to approach it with a plan of action. Hepworth and Church’s paper proposes a multi-step plan, to best ethically create a digital project. This plan had three phases (pre-data collection, data curation and collection, and data visualizing and argumentation). Between the three phases outlined, Hepworth and Church propose nine steps (defining the field of inquiry, reviewing the latest subject scholarship, collecting primary documents and artifacts, pruning non-viable primary documents, describing primary data in a custom data set, surveying ethical visualization literature, pre-visualizing context consideration, visualizing data, and publishing data).

Of the steps and phases that Hepworth and Church lay, I believe that surveying and pre-visualizing is one of the most important ethical considerations. The inclusion of a test audience or test projects draws a distinction between maxim-based, or deontological ethics, and consequential ethics. While I believe that deontological ethics has some merit, I also believe that the consequential aspect of digital projects is the more important consideration. The saying “the road to hell is paved with good intentions” is important here. One’s purpose for creating a project could be neutral or positive, but its actual consequence is negative. Take the AI Twitter Chatbot for example. The maxim behind the creation of this bot was to create a fun experiment (an ethically neutral to the positive distinction), however, the consequence was a racist chatbot (an ethically negative distinction). Bluntly, in consideration of publishing a widespread digital project, intention does not matter (at least not to the same extent as consequence).

The examination of maxims and consequences can be evaluated in the two digital humanities projects that were outlined in the reading, “Lynching in America: Racial Terror Lynchings” and “White Supremacy Mob Violence.”

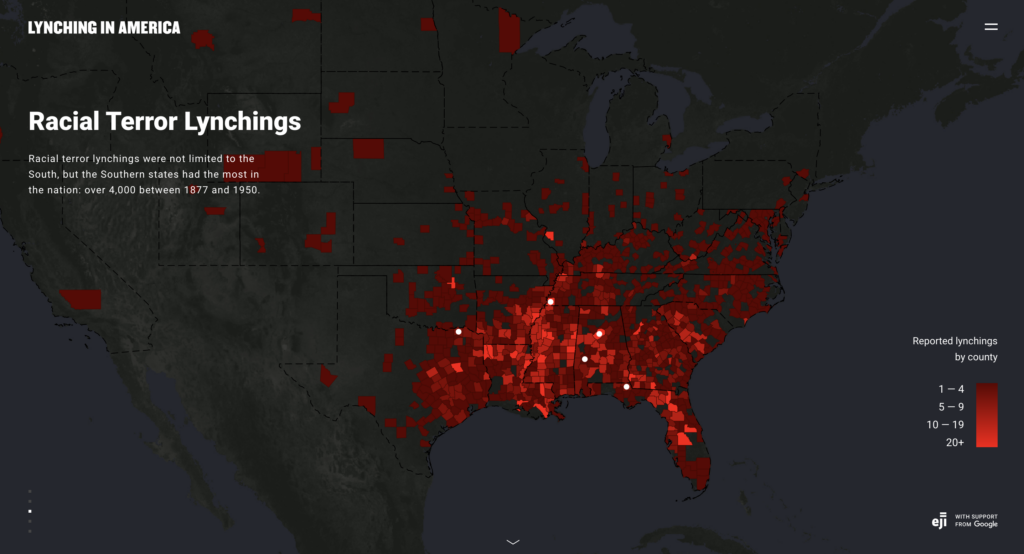

A screen grab of the current “Racial Terror Lynchings” Project

The intention of “Lynching in America; Racial Terror Lynchings” was to be part of a larger group’s work on prison reform. However, the consequences of this project do not ethically reflect the noble maxim of the project. The first problem, as outlined by Hepworth and Church, is that it initially made little consideration for lynchings that occurred outside of the Deep South. When it did consider these lynchings, it still only considered African American lynchings. The consequence of this project is that it becomes less of an argument and more of an assertion. The assertion is that African Americans were the sole victims of lynching and that this act of terror was a predominantly geographic problem.

Without clearly presenting the evidence, or presenting any other information on lynchings that occurred against non-African American individuals, the project does not allow the viewer to think for themself, and draw a conclusion outside of the assertion made. Instead, the project asserts its own (incorrect) conclusions to the reader, a conclusion that is backed by its purpose as a tool for prison reform. The issue with the argument of this project is not that it is a weak one, terror lynchings on a racial basis are a well-backed historical event (especially those committed against African Americans). The issue is also not that the cause of the project is bad. The issue is that there is no argument at all, instead the project is an assertion that gives in inaccurate understanding of lynchings.

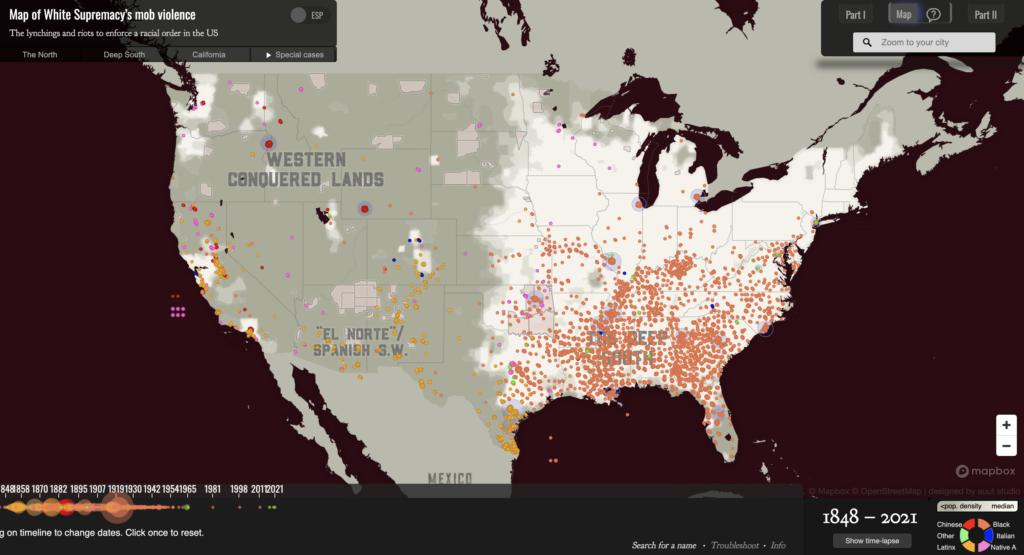

A screen grab of the “White Supremacy’s Mob Violence” map

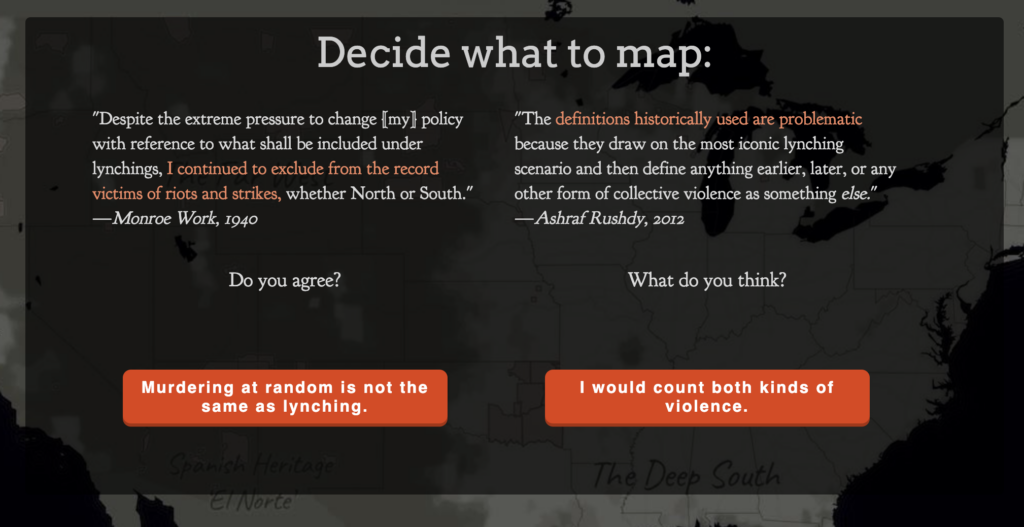

A picture of some of the interactive features of the “White Supremacy Mob Violence Project”

Provided as an alternative to the “Lynching in America” project, the “White Supremacy Mob Violence Project” provides a more ethical example of its consequence. The first striking difference between the two is how much more interactive this project is. Throughout the project, the reader is provided with choices. They can choose whether they consider something murder or not. They can choose whether or not they want to see the sources of information. The reader is provided definitions and examples to inform these choices. Within the actual map, each instance of lynching is given information. A person’s name, or at least identifying features is given (as well as the known reason for the lynching). The race of the person lynched is also given (a stark contrast from the information presented in the first project). The consequences of this project are an argument, not an assertion. With the information given to the viewer of the project, the project argues for the reader to evaluate. Looking at the races of people lynched, the reasons for the lynchings, and the dispersal of the lynching, the reader is left with the argument that these were racially influenced hate crimes.

Both projects have noble maxims. The first project intends to call to mind the problems with the modern prison system, especially the problems faced by African American men. The second project intends to highlight America’s historic problem with white supremacy’s mob violence. However, it is the consequences that distinguish to two ethically. The consequence of the first project draws an asserted conclusion that leaves out information and can be seen as misleading to an audience on the historical violence that occurred. The consequence of the second project is an informed viewer who can consider a strong argument on the racial motivations behind lynchings.

Bibliography

EJI and Google. “Lynching in America: Racial Terror Lynchings.” https://lynchinginamerica.eji.org/explore

Hepworth, Katherine and Christopher Church. “Racism in the Machine: Visualization Ethics in Digital Humanities Projects.” Digital Humanities Quarterly. Vo. 12, no. 4 (2018).

Monroe and Florence Work. “White Supremacy Mob Violence.” https://new.express.adobe.com/webpage/nKAyaWTMZtLxS/