The UK, whilst appearing as a relatively unimpressive island adjacent to continental Europe, is somehow, throughout most of history, the luckiest empire in the world. In addition to colonizing over half the globe, when the Industrial Revolution rolled around, British people seemed to luck out once more, realizing their island is a giant mountain of coal.

Winchester, Simon. “A Land Awakening from Sleep.” The Map That Changed the World, Harper, 2001, p. 26.

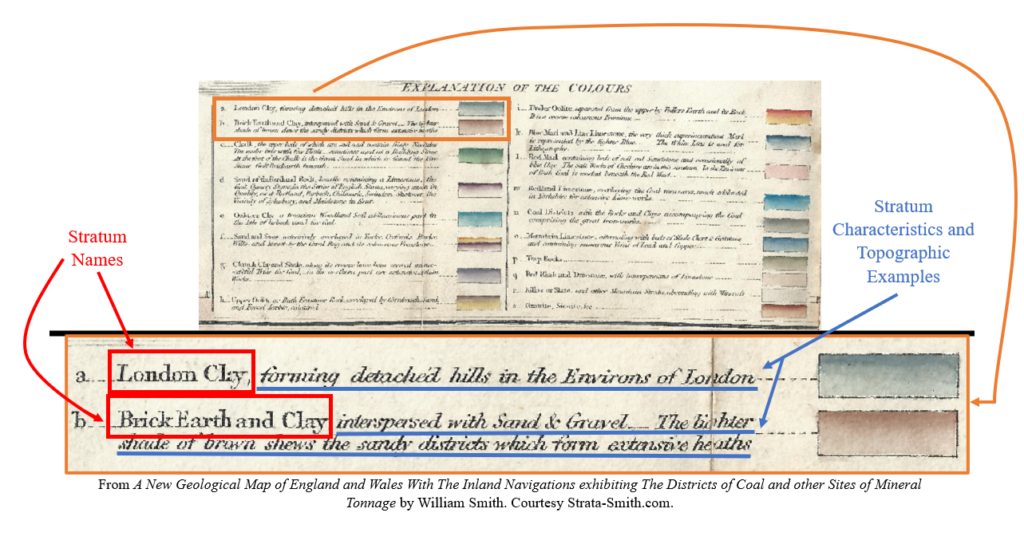

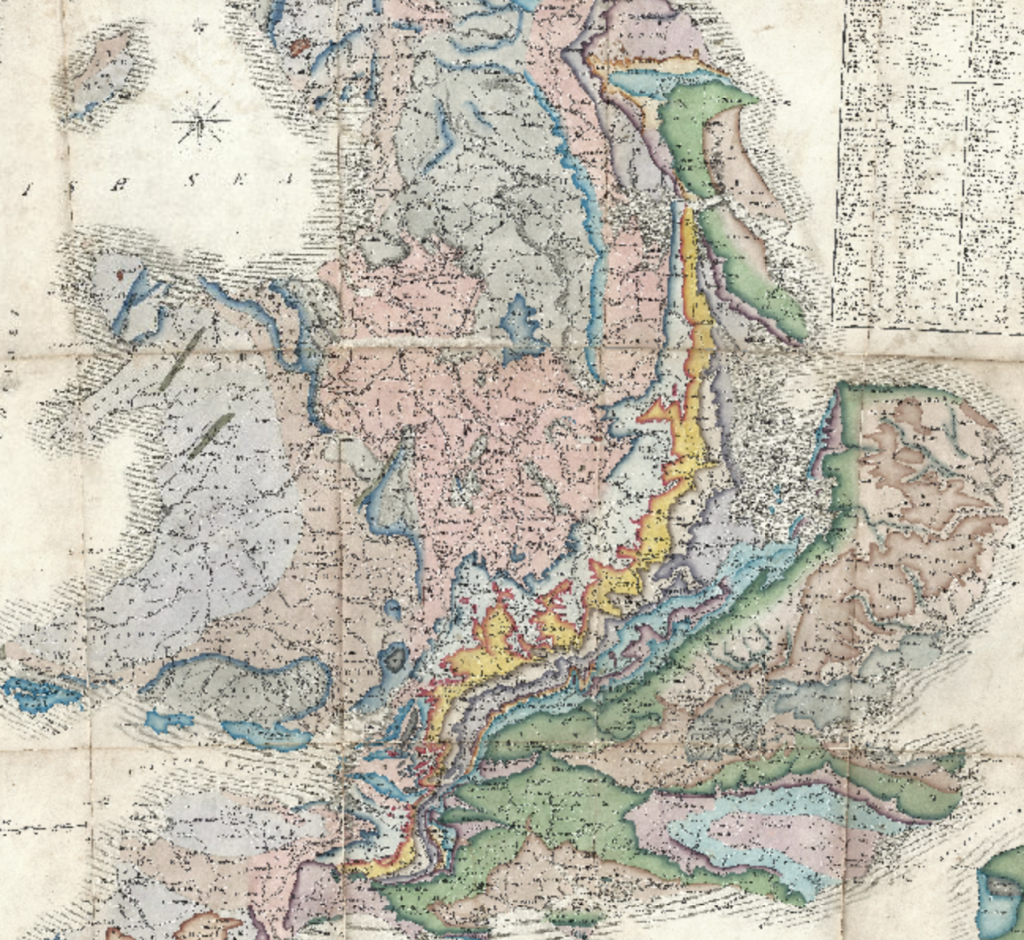

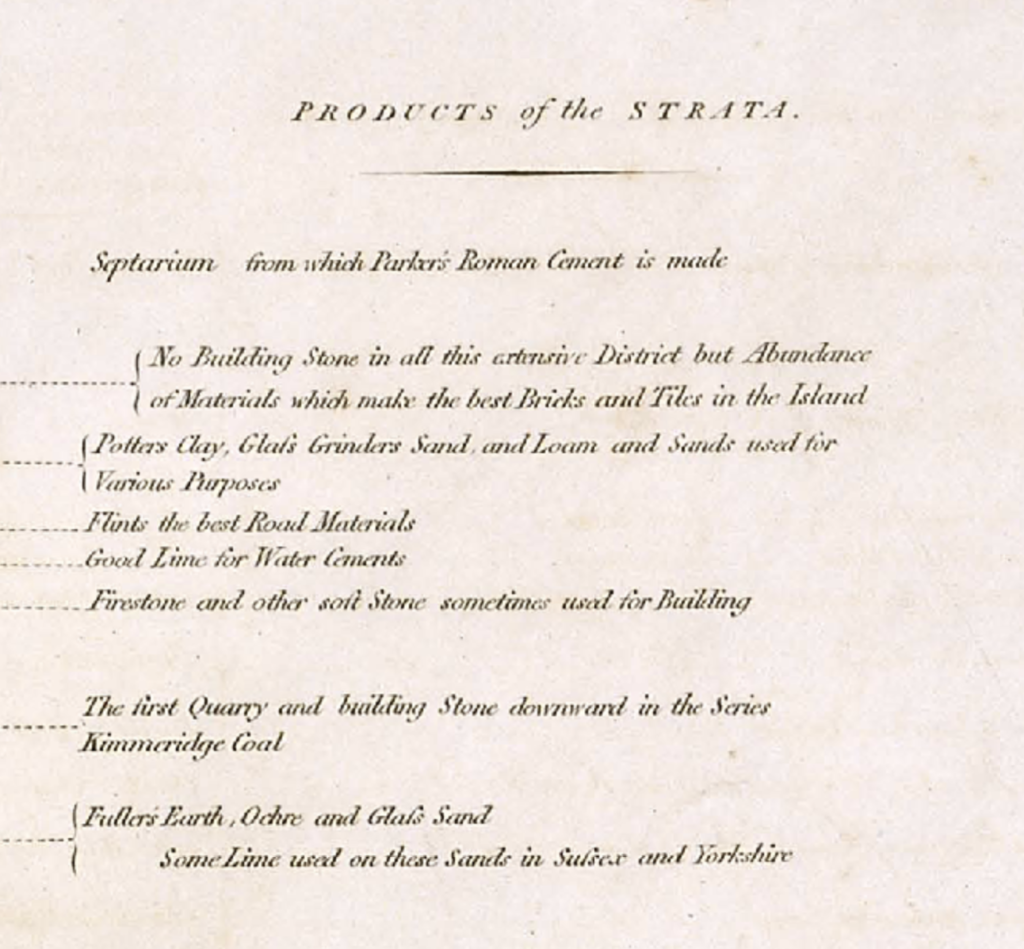

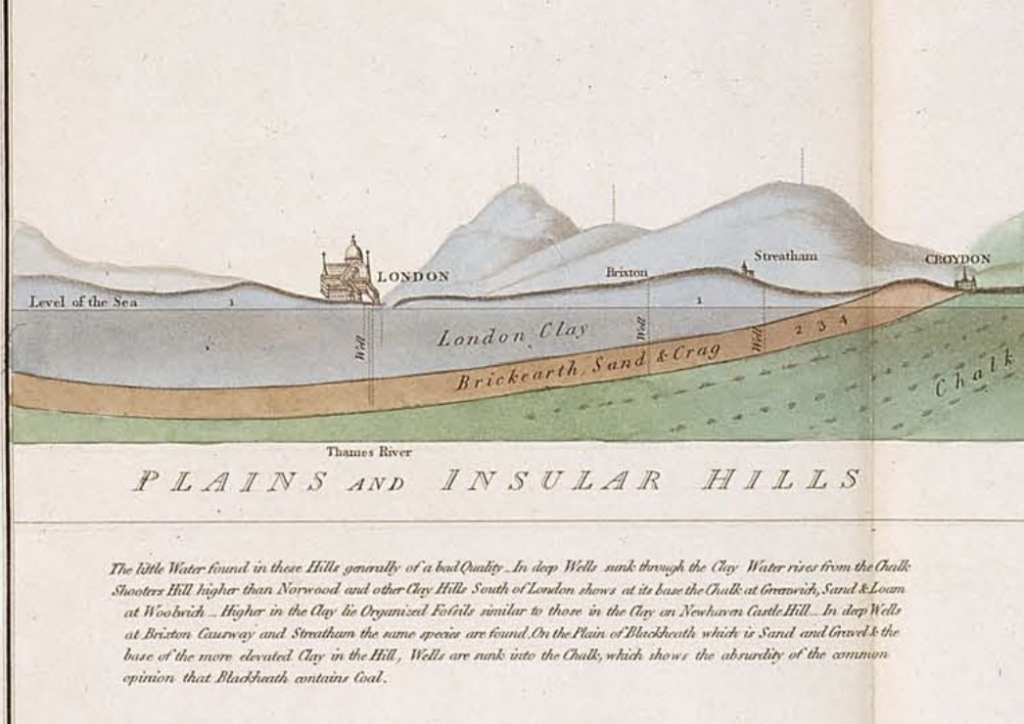

However, Smith was more interested in rock stratification and fossils than coal. He mapped the stratifications of rock and rock layers in great detail.

William Smith’s Geological Map of England and Wales, from http://www.strata-smith.com/map/.

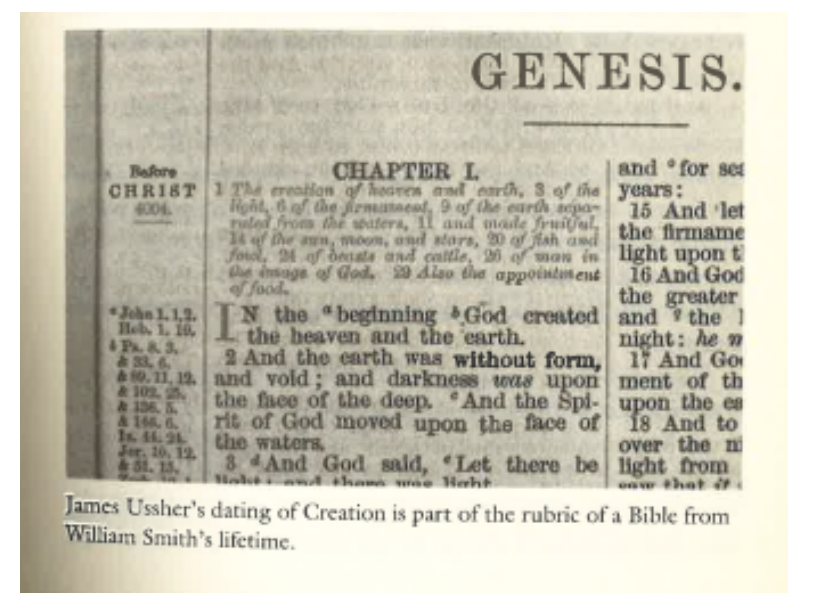

William Smith’s research worked in tandem with a relatively new and radical thought: the world existed long before the story of creation in the Bible’s Genesis.

From https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/features/WilliamSmith.

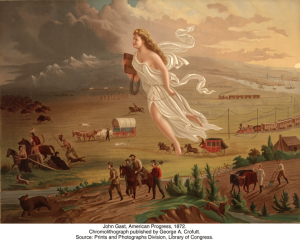

The questioning of literal Biblical interpretations spurred not only Smith’s research, but industrialization itself. In order to use the coal found, they had to shun the idea that the world didn’t exist until humans came along. This also shifted the perspective that natural laws governed the physical world, rather than metaphysical/theologian laws/ideas governing the physical world. William Smith’s map came at a time when there was a shifting emphasis to scientific explanation and reason than focus on the spiritual.

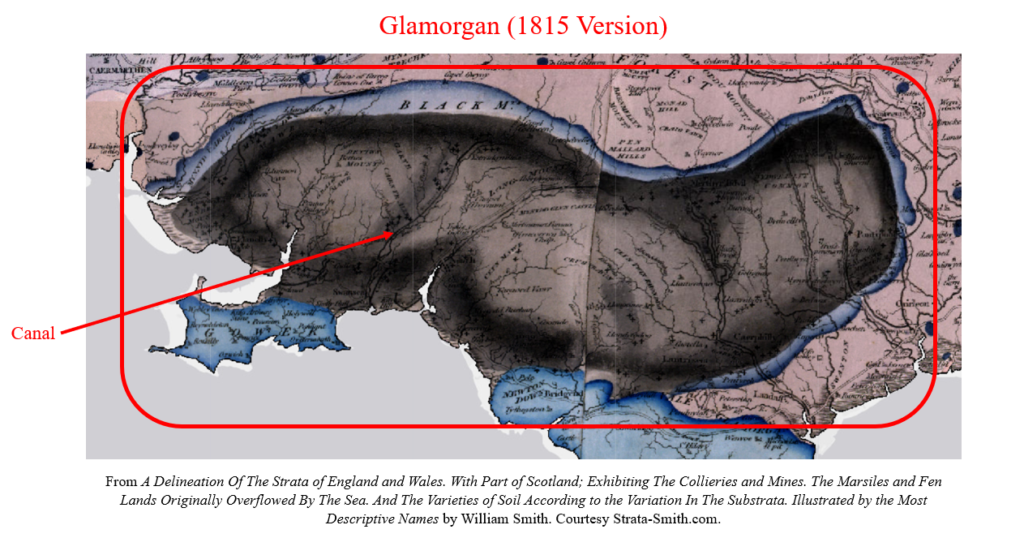

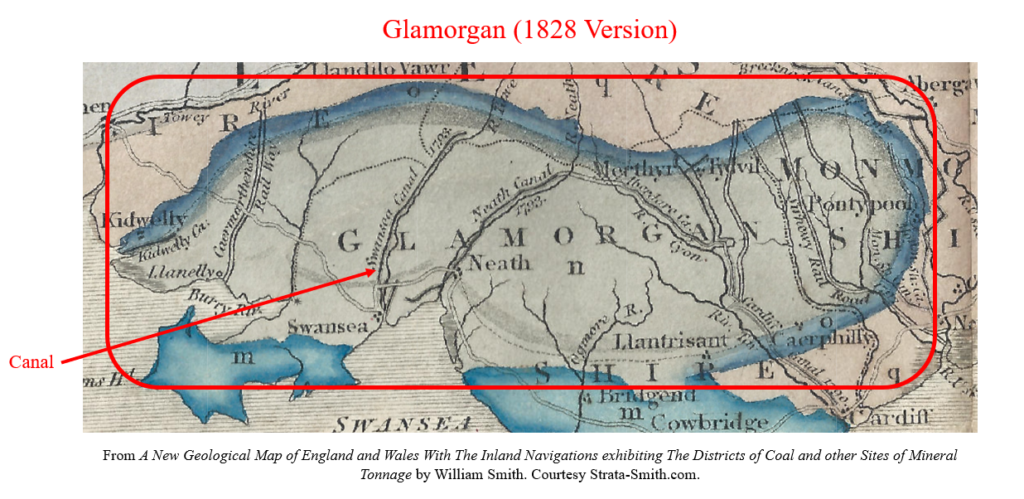

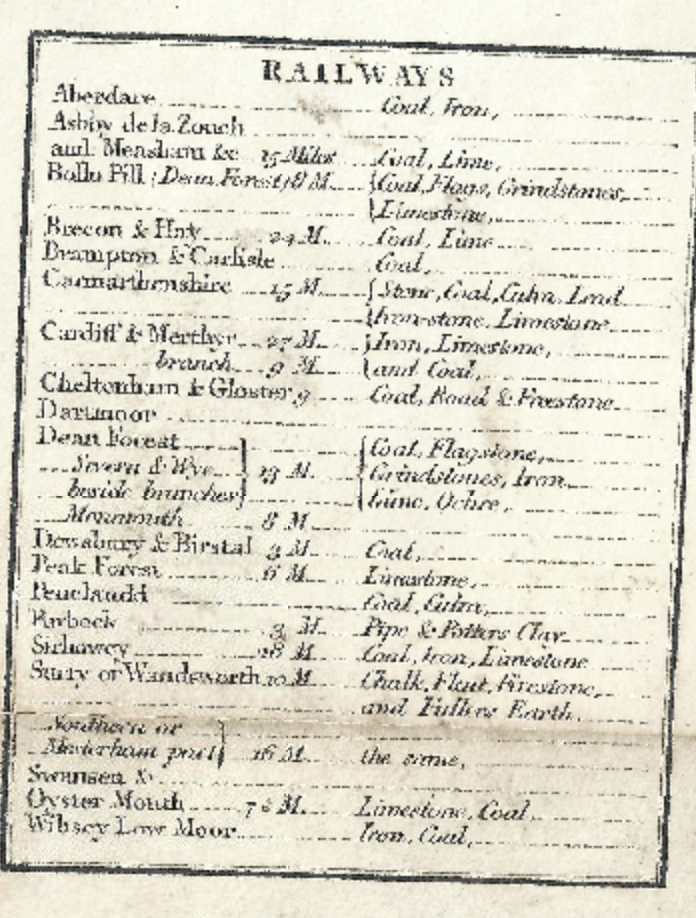

Although Smith’s map is crucial to understanding the world and what lies beneath, his map didn’t do well, as the British government seemed to trend more towards mapping coal mines and points of monetary value, rather than academic. Later, these maps were important for the transportation of coal through digging canals around England, but were relatively overlooked until then, with Smith rotting in a debtor’s prison and living in poverty upon his release. Later, when the Industrial Revolution kicked into full-steam, his maps were crucial in water management (aquifers identified), location of coal deposits, and canal construction.